Final Report

Evaluation and Advisory Services

Transport Canada

March 2015

Table of Contents

- Tables and Figures

- List of Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- About the Evaluation

- Evaluation Findings: Relevance

- Evaluation Findings: Performance

- Conclusions, Lessons Learned and Observations

- Annex A: Immediate outcomes

Tables and Figures

- Table 1: Expected Outcomes or Deliverables by Initiative

- Table 2: Clean Transportation Initiatives by Area Responsible for Delivery

- Table 3: Resources Allotted by Initiative

- Table 4: Contribution of the Transportation Sector to Air Pollutant Emissions, 1990-2012 (Kilotonnes)

- Table 5: Percentage of Allotted Money Spent by Initiative

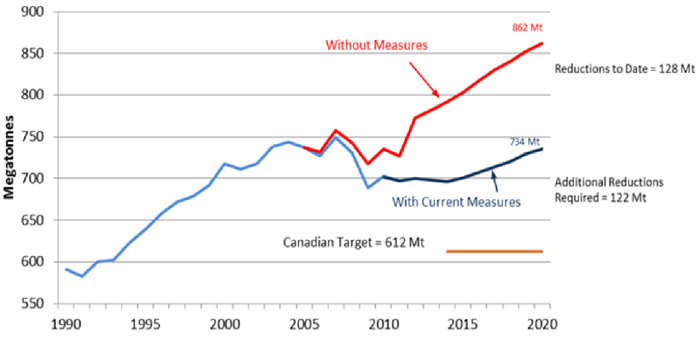

- Figure 1: Historical and Projected Trends in GHGs Emissions in Canada (MT of CO2e), 1999-2020

- Figure 2: Trends in GHGs Emissions from Transportation, 1990-2020 (Mt of CO2e)

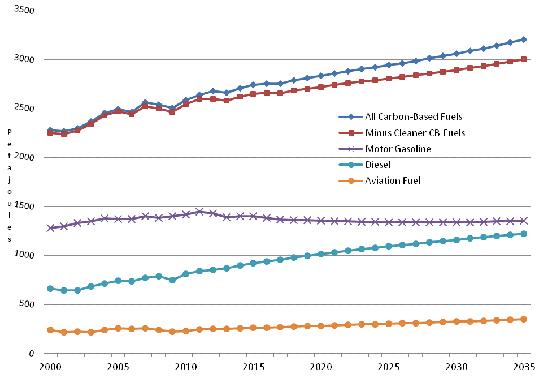

- Figure 3: Energy Consumption Trends in Canada, 2000-2035 (in Petajoules)

List of Acronyms

- CAC

- Criteria air contaminants

- CAEP

- Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection

- CEESAR

- Centre of Excellence in Economics, Statistics, Analysis and Research

- CEPA

- Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

- CO2

- Carbon dioxide

- CO2e

- Carbon dioxide equivalent

- CTI

- Clean Transportation Initiatives (Next Generation)

- DG

- Director General

- EC

- Environment Canada

- eTV II

- ecoTECHNOLOGY for Vehicles II Program

- GHG

- Greenhouse Gas

- HDVs

- Heavy-duty vehicles

- ICAO

- International Civil Aviation Organization

- IMO

- International Maritime Organization

- kt

- Kilotonnes

- LDV

- Light-duty vehicle

- LEIS

- Locomotive Emissions Information System

- LEM

- Locomotive Emissions Monitoring Program

- MEPC

- Marine Environment Protection Committee

- MOU

- Memorandum of understanding

- Mt

- Megatonnes

- MVSA

- Motor Vehicle Safety Act, 1993

- NA ECA

- North American Emission Control Area

- NOx

- Oxides of nitrogen

- NRC

- National Research Council

- nvPM

- Non-volatile particulate matter

- PMV

- Port Metro Vancouver

- PWGSC

- Public Works and Government Services Canada

- LDVs

- Light-duty Vehicles

- R&D

- Research and development

- RAC

- Railway Association of Canada

- RCC

- Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council

- RTK

- Revenue tonne-kilometres

- SDS

- Sustainable Development Strategy

- Sox

- Oxides of sulphur

- SPTP

- Shore Power Technology for Ports

- TC

- Transport Canada

- TRSP

- Truck Reservation System Program

Executive Summary

The evaluation of the Next Generation of Clean Transportation Initiatives ( CTI ) was conducted to inform the renewal of clean transportation programming and to access on-going funding. The CTI consists of eight Transport Canada ( TC ) initiatives or programs, and one Environment Canada ( EC ) initiative, all designed to ultimately reduce greenhouse gas ( GHG ) and air pollutant emissions from the transportation sector.

The CTI was part of the Government of Canada’s renewal of the Clean Air Agenda, announced in Budget 2011. It is a five-year (2011-12 to 2015-16), $148 million suite of initiatives that deliver new or amended regulatory frameworks; new or updated compliance and oversight regimes; scientific and technology, and socio-economic or policy research, data development and modeling projects; funding for the implementation of new technologies at Canadian ports through contributions; voluntary initiatives with industry; and the provision of input into standards, codes, protocols, guidelines and related instruments.

The CTI is overseen by the Environmental Policy Directorate of TC’s Policy Group at National Headquarters. Activities are delivered through 11 branches within TC and the Transportation Division of Environment Canada.

Evaluation Scope and Approach

The evaluation was conducted in the summer of 2014 and covers mostly the first three fiscal years of the CTI . As most of the outcomes from the regulatory changes were not expected to materialize until after 2015-16, the evaluation focused on the implementation of the initiatives, the achievement of short-term outcomes and the reporting of early and partial results. As per the Policy on Evaluation, the evaluation also examined program relevance and efficiency and economy.

The evaluation was based mostly on the review, compilation and analysis of administrative and performance information from the programs delivering the initiatives. Progress was compared against emission reduction targets; deliverables and timelines outlined in foundational documents; and the initiatives’ Performance Measurement Strategy.

Major Findings

The evaluation found that there is an ongoing need for the regulatory initiatives, including the research, and testing and evaluation activities supporting them. The relevance of these initiatives is rooted in the departments’ on-going need to develop and align their regulatory frameworks with international regulatory frameworks to which Canada has made commitments or has obligations to align; and to negotiate with international governing bodies to develop frameworks that meet Canadian needs. Activities such as research and testing and evaluation of technologies, and financial support for the implementation of technologies are well aligned with the objective of improving emissions intensity as a way to reduce overall emissions.

In the first three years, the regulatory initiatives and their supporting activities have been implemented with diligence. Although some of the anticipated regulatory changes to address emissions have experienced delays, evaluators found that progress is being made, appropriate to the stage of implementation. Delays encountered were mostly due to circumstances outside the control of the departments, such as delays in the pace of negotiations or discussions at the International Civil Aviation Organization ( ICAO ) or the International Maritime Organization ( IMO ). For similar reasons, the take-up for contribution funding was slower than expected and it is unlikely that the contribution programs will deliver all of their expected results within the five-year time frame.

Although it is too early to measure the extent to which regulatory initiatives are making progress in achieving their specific emission reduction targets, evaluation findings presented in this report suggest that the CTI has made progress in achieving short-term outcomes. Since 2013, vessels navigating in the North America Emissions Control Area ( NA ECA ) have to comply with new regulations requiring the use of cleaner fuel. Voluntary measures implemented by industry associations as part of Canada’s Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gases from Aviation and the Memorandum of Understanding between Transport Canada and the Railway Association of Canada for Reducing Locomotive Emissions are achieving results in terms of improved fuel efficiency or emissions intensity. The Shore Power Technology for Ports Program has demonstrated results in reducing emissions at Port Metro Vancouver ( PMV ). Similarly, data obtained from managers of the Truck Reservation System Program provide early evidence that the TRSP is having an impact as well at the PMV , through reducing the amount of time trucks are idling.

Finally, the ecoTECHNOLOGY for Vehicles II Program ( eTV II ), research and development and other research activities have resulted in new knowledge in support of regulatory work and the development of international and Canadian standards, codes, protocols, guidelines and related instruments.

Partial and early results lead to the conclusion that the CTI is contributing or will contribute to the reduction of GHGs and air pollutant emissions from transportation. However, at the time of the evaluation, it was not possible to determine if all the initiatives that have emission reduction targets are likely to reach them.

The overall oversight of the CTI was carried-out using good practices. After the first two years, an implementation review was conducted and it led to some recommendations and improvement in the management of the initiatives. Going forward, program managers might want to improve the on-going collection of data as per the Performance Measurement Strategy.

Conclusions

Evaluation findings support the renewal and continuation of the five regulatory initiatives, including the continuation of the activities and initiatives that support them; such as research and development ( R&D ), other types of research, and eTV II .

There is a continuing need for the Government of Canada to exercise leadership and provide financial support to the private sector in implementing other new emission reduction technologies. However, consideration should be given to expanding the reach of such programs, to maximize uptake and the impact of available funds.

TC and EC are making progress toward achieving short term results and there is evidence that progress is being made in terms of achieving medium term ones (improved emissions intensity and promoting the adoption of technologies and practices that improve emissions intensity by the transportation sector). In addition, there is evidence of TC having demonstrated efficiency (i.e. leveraging of resources) and economy (i.e. cost savings) in the utilization of resources.

Introduction

The evaluation of the CTI was conducted between June 2014 and September 2014 to inform the renewal and planning of new programming related to transportation within the Clean Air Agenda, and to access ongoing funding. Budget 2011 conditioned this access on a full evaluation by 2015. However, it was decided to renew these programs in 2014-15 and the evaluation had to be conducted earlier than planned. This evaluation will also contribute to meeting the requirement of Treasury Board’s Policy on Evaluation that all direct program spending be evaluated over a five-year cycle.

Background

As part of Budget 2011, the Government of Canada announced an investment of $148 million to develop regulations for the transportation sector through the Next Generation of Clean Transportation Initiatives. This funding was for the second phase of the Clean Transportation theme under the Government of Canada’s Clean Air Agenda, which was launched in 2007 to reduce emissions from the transportation sector.

Program Profile

The Next Generation of Clean Transportation Initiatives ( CTI ) consists of nine initiatives, eight of which are being delivered by TC and one of which is being delivered by EC . These initiatives are as follows:

- Aviation Sector Regulatory Initiative

- Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative, TC

- Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative, EC

- Rail Sector Regulatory Initiative

- Support for Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations Initiative

- ecoTECHNOLOGY for Vehicles II Program

- Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative

- Truck Reservation System Program

- Shore Power Technology for Ports Program

The CTI was designed to build-on or expand activities previously undertaken by the departments. While a previous suite of initiatives evaluated in 2010 focused on technology demonstration and behavioral change to reduce emissions, the new suite focuses on regulatory change across all modes of transportation and technological deployment to achieve the same objectives.

Objectives

The long term objective of the CTI is to reduce the emission of air pollutants and greenhouse gases from transportation. To reach this objective, the initiatives are delivering activities that should produce in the medium term, two main results:

- A transportation sector that is adopting technologies and practices that improve emissions intensity for air pollutants and greenhouse gases, with safety and efficiency benefits; and

- Funded projects that improve emissions intensity of air pollutants and greenhouse gases, with safety and efficiency benefits.

Activities

The five regulatory initiatives - for the aviation, marine ( TC and EC ), rail and on-road vehicles sectors - are expected to deliver new or amended regulatory frameworks; regulatory compliance and oversight; voluntary agreements with industry; and/or input into the development of standards, codes, protocols, guidelines and other related instruments, whether Canadian or international. They are also expected to deliver scientific and technology studies and results; and policy or socio-economic studies, and improved data and statistical models in support of the regulatory work (see Table 1).

Two initiatives (the Truck Reservation System Program and the Shore Power Technology for Ports Program) are expected to deliver funding to support the implementation of technologies and systems at Canadian ports.

One initiative, the Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative, is a specific data development/modeling initiative to develop a carbon footprint calculator and measure the carbon footprint from transportation in three of Canada’s gateways and corridors.

eTV II is a testing and evaluation program for light-duty vehicles ( LDVs ) and heavy-duty vehicles ( HDVs ). It delivers testing and evaluation results on the safety and environmental performance of new and emerging technologies that manufacturers are implementing in new vehicles to meet increasingly stringent environmental and safety standards. These results, in turn, are used to inform regulatory development to ensure that new technologies achieve their anticipated environmental benefits and can be safety introduced in Canada. Results are also used to support the development of codes, standards, test protocols and guidance materials required by industry to adopt new clean technologies.

Expected results

In the short term, the CTI is expected to produce four immediate results:

- A transportation sector in which regulated segments comply with the regulations;

- A transportation sector in which targeted segments participate in non-regulatory emission reduction agreements;

- A transportation sector that is informed of targeted clean transportation technologies and practices; and

- Clean transportation projects that are completed as per the funding agreements.

Emission reduction targets were established for some initiatives, while for others, none were identified because they contribute only indirectly to emission reductions, e.g. eTV II .

Table1: Expected Outcomes or Deliverables by Initiative

| Environment and Safety Regulatory Frameworks | Regulatory Compliance and Oversight | Voluntary Agreements with Industry

Associations |

Input into Standards, Codes, Protocols, Guidelines and Related Instruments | Scientific, Technology, and Socio-Economic or Policy Research Projects and Results | Funding for Clean Transportation Projects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aviation Sector Regulatory Initiative | yes• | yes• | yes• | yes• | yes• | |

| Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative | yes• | yes• | yes• | yes• | ||

| Rail Sector Regulatory Initiative | yes• | yes• | yes• | yes• | yes• | |

| Support for Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations | yes• | yes• | yes• | yes• | ||

| ecoTECHNOLOGY for Vehicles II Program | yes• | yes• | yes• | |||

| Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative | yes | |||||

| Truck Reservation System Program | yes• | yes• | ||||

| Shore Power Technology for Ports Program | yes• |

Program Delivery and Resources

The CTI is overseen by the Environmental Policy DirectorateFootnote 1 within the Policy Group. Its delivery involves 12 branches and two departments, with Environmental Policy being involved in all but three of the initiatives (see Table 2).

Table 2: Clean Transportation Initiatives by Area Responsible for Delivery

| Initiative | Branch |

|---|---|

| Aviation Sector Regulatory Initiative | Standards Branch (Civil Aviation) |

| Environmental Management Branch (Stewardship and Sustainable Transportation Programs) | |

| Economic Analysis - Centre of Excellence in Economics, Statistics, Analysis and Research ( CEESAR ) | |

| Environmental Policy Analysis and Evaluation (Environmental Policy) | |

| Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative | Navigation Safety and Environmental Programs (Marine Safety) |

| Economic Analysis ( CEESAR ) | |

| Transportation Development Centre ( CEESAR ) | |

| Environmental Policy Analysis and Evaluation (Environmental Policy) | |

| Transportation Division (Environment Canada) | |

| Rail Regulatory Initiative | Rail Safety Operations |

| Environmental Policy Analysis and Evaluation (Environmental Policy) | |

| Economic Analysis ( CEESAR ) | |

| Transportation Development Centre ( CEESAR ) | |

| Environmental Management Branch (Stewardship and Sustainable Transportation Programs) | |

| Support for Vehicle Green House Gas Emission Regulations | Motor Vehicle Standards, Research and Development |

| Economic Analysis ( CEESAR ) | |

| Environmental Policy Analysis and Evaluation (Environmental Policy) | |

| ecoTECHNOLOGY for Vehicles II Program | Environmental and Transportation Programs Branch (Stewardship and Sustainable Transportation Programs) |

| Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative | Environmental Policy Analysis and Evaluation (Environmental Policy) |

| Truck Reservation System Program | Innovation Policy |

| Marine Policy | |

| Shore Power Technology for Ports Program | Environmental and Transportation Programs Branch (Stewardship and Sustainable Transportation Programs) |

The CTI was allocated $148. 0 million over five years (2011-12 to 2015-16), including $35.1 million for grants and contributions and $54.2 million for Other Operating Costs. The average annual number of FTEs allotted over the five-year time frame for the entire initiative is 10.4.

Table 3: Resources Allotted by Initiative

| Initiative | Total $ 2011-12 to 2013-14* | Total $ 2011-12 to 2015-16* | FTEs over 5 years (Annual Average) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aviation Sector Regulatory Initiative | 8,175,578 | 12,878,555 | 10.5 |

| Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative ( TC ) | 13,628,919 | 22,633,817 | 17.5 |

| Rail Sector Regulatory Initiative | 8,930,765 | 14,685,332 | 11.2 |

| Support for Vehicle Green House Gas Emission Regulations | 6,245,345 | 10,167,424 | 11.1 |

| ecoTECHNOLOGY for Vehicles II Program | 22,645,337 | 37,967,800 | 28.2 |

| Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative | 985,821 | 1,493,254 | 1.9 |

| Truck Reservation Systems Program | 3,790,896 | 7,500,000 | 0.4 |

| Shore Power Technology for Ports Program | 12,057,612 | 30,000,004 | 4.1 |

| Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative ( EC ) | 6,600,000 | 10,700,000 | 8.4 |

| Total | 83,060,273 | 148,026,186 | 10.4 |

* These financial data include Public Works and Government Services Canada ( PWGSC ) amounts.

Governance

The CTI is governed by a Director General ( DG ) level Clean Transportation Steering Committee (headed by DG , Environmental Policy) and a Director-level Clean Transportation Coordinating Committee. These committees cover both financial and non-financial monitoring and provide leadership on the management of the initiatives’ budgets and future direction. The DG -level committee has met eleven times since 2012 and the Director-level committee has met eight times since its creation in 2014.

There are three Technical Working Groups: Clean Aviation, Marine and Rail. The Clean Aviation Technical Working Group reviews project proposals and approves funding amounts for the research work done under the Aviation Sector Regulatory Initiative. The Marine and Rail Working Groups support the mandate of the TC Director-level Research, Development, and Technology Deployment Committee and provide advice and technical expertise on the marine and rail projects identified in the work plan.

There are also separate oversight mechanisms in place for the Shore Power Technology for Ports Program and the Truck Reservation System Program, in accordance with TC governance of transfer payment programs. The eTV II Program has two technical working groups (light-duty and heavy-duty vehicles), in addition to a Director General Interdepartmental Steering Committee – all of which provide technical and program governance.

A Mid-Program Assessment covering the first two fiscal years of the CTI was completed in the winter of 2013. Its main objective was to review the implementation status of the initiatives and determine whether course corrections were required and, if so, what those should be. Information on outputs and spending was collected and reported against the Sustainable Development Strategy commitments and the output indicators of the Performance Measurement Strategy. The intent of this type of dual reporting was to ensure that all relevant performance information was captured, although this resulted in some overlap and repetition of reported results. The assessment did not include EC’s Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative.

Some recommendations for improvement were made, including the need for support in the area of contracting and financial coding, the need to extend funding for the Shore Power Technology for Ports Program to other port technologies, the need to undertake a broader call for proposals for the Truck Reservation System Program and the need to facilitate multi-year funding for research and testing with the National Research Council ( NRC ).

About the Evaluation

The evaluation of the CTI was conducted between June 2014 and September 2014 to inform the renewal and planning of new programming related to transportation within the Clean Air Agenda; and to access ongoing funding. It is expected that this evaluation will also contribute to meeting the requirement of Treasury Board’s Policy on Evaluation that all direct program spending be evaluated over a five-year cycle.

Evaluation Scope and Methodology

Considering that this evaluation was undertaken early in the life cycle of the CTI , when not all of the regulations had yet been implemented, evaluators focused data gathering and analysis on the following performance issues:

- The extent to which the initiatives have been implemented as planned.

- Progress toward achieving immediate results: engaging industry associations in participating in non-regulatory emission reduction agreements; informing the transportation sector (and governing bodies) of clean transportation technologies and practices; and having transportation projects completed as per the funding agreements.

- Progress toward achieving emission reduction targets.

Since the only changes made to regulatory frameworks over the first three years of the initiative were recent, with less than a year’s worth of data available for analysis, evaluators did not assess the extent to which regulated segments of the transportation sector comply with the new or amended regulations. In addition, as per the Policy on Evaluation, the evaluation examined program relevance and, to the extent possible, whether efficiency and economy could be demonstrated in the utilization of resources.

Results were assessed by comparing progress achieved in relation to the following: 1) the emission reduction targets outlined in foundational or other documents, 2) the deliverables and time lines to which TC committed, and 3) the indicators listed in the CTI’s Performance Measurement Strategy. The evaluation included the lines of inquiry outlined below:

A document review examined strategic and foundational program documents; program reports, survey results and special studies; regulatory impact analysis statements, triage, consultation reports and cost-benefit analyses produced for the regulatory initiatives.

An analysis of performance and administrative data included primary and secondary data, such as trend data on greenhouse gas ( GHG ) emissions from EC’s national inventory, data from annual reports related to Canada’s Action Plan to Reduce Green House Gas Emissions from Aviation and the Locomotive Emissions Monitoring Program and available data for other indicators outlined in the Performance Measurement Strategy provided by program managers. It also included financial data relevant to the initiatives, other administrative data, planning documents, and any data fact books, inventories or compilations helpful to understanding the relevance and performance of the initiatives and whether the Performance Measurement Strategy had been implemented.

A project file review was conducted to examine expected and actual results achieved by the two contributions programs.

A literature review looked at research literature dealing with issues, trends, policies and best practices related to transportation and air quality or GHGs emission reduction.

Interviews with some 20 directors, program managers and analysts at TC and EC were conducted to gain a better understanding of the relevance of the initiatives, the departments’ performance, and to validate evaluation findings and their interpretation.

Evaluation Considerations

A number of considerations and limitations influenced the conduct of the evaluation.

The programs developed a comprehensive and detailed Performance Measurement Strategy, which included the collection of information on a number of indicators, making the Strategy information-heavy. At the same time, the Performance Measurement Strategy had not been fully implemented (e.g. taking an annual stock of some of the indicators laid out in the Strategy, as required by the Strategy). Evaluators were able to obtain most of the required information, often requiring great effort from evaluators and program staff.

Financial data for the initiatives are available only by initiative and branch. Most of the initiatives contain multiple components (e.g. changes to regulatory frameworks, voluntary agreements with industry, international participation in the development of regulatory frameworks and research). A more detailed coding of the financial data for the initiatives would have been beneficial to understanding how much money was allocated and spent on major components of the initiatives. It would also have helped better align the financial information with the Performance Measurement Strategy and would have allowed for a comparative understanding of the value for money spent.

Also, emission reduction targets were identified for five of the nine initiatives (the aviation, marine, and rail regulatory initiatives and the two contribution programs). For most of these initiatives, concrete data will not be available until completion of the initiatives, and in many cases, the target date for the reductions is 2020. The amended Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations is a case at point. While baseline data are available to measure the amended regulations’ impact, it will not be possible to measure their early impact until much later because Marine Safety will not be conducting its vessel pollution release inventory until after 2016, once the most stringent standards have been in place for a period of time. Even then, the date for achieving the full emission reduction target is 2020. In such cases, evaluators focused on providing any evidence of immediate impact on emissions as opposed to whether emission reduction targets will be met.

The remaining initiatives and large components of the marine, rail and aviation sector regulatory initiatives do not have emission reduction targets as they contribute only indirectly to emission reductions, through activities such as research, input to codes, etc. (see Table 1 on Page 6). Results for these initiatives and components, which account for approximately 60 percent of the funding allocated to the overall initiative, were assessed using the indicators in the Performance Measurement Strategy. Because these initiatives and components generate emissions reductions only indirectly, and because of an absence of data on the ultimate amount of emission reductions that will be achieved, due in part to the timing of the evaluation, evaluators were not able to assess program effectiveness. For these same reasons, evaluators focused on economy, in particular, whether resources were utilized prudently; and in the case of efficiency, used any data which could be found relating to operational efficiency rather than allocative efficiency.

Evaluation Findings: Relevance

To assess the continuing relevance of the CTI , the evaluation examined whether the initiatives were in line with the roles and responsibilities of the federal government, the priorities of the federal government and departmental strategic objectives. The assessment also involved a consideration of whether there is an ongoing need and policy rationale for the initiatives.

Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Finding 1: The delivery of the clean transportation initiatives is in line with the roles and responsibilities of the federal government and is within the legislative authorities and mandates of Transport Canada and Environment Canada.

The Government of Canada’s constitutional roles and responsibilities to regulate emissions from transportation and regulate on other matters such as transportation safety and the competitiveness of the transportation system stem indirectly from constitutional provisions regarding commerce and trade, and navigation and shipping.

TC’s legislative framework defines its roles and responsibilities regarding emission regulation, their enforcement and the implementation of supportive activities. For the marine mode, TC has the authority to regulate under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 (the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations). Under the Railway SafetyAct (the proposed Locomotive Emissions Regulations), it has the authority to regulate rail transportation. It regulates the aviation industry under the Aeronautics Act (the Canadian Aviation Regulations). TC can also affect emissions in Canada’s northern waters through the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act.

The Canada Transportation Act, 1996 makes the efficiency and competitiveness of the transportation system a federal responsibility as well, for the air, marine and rail modes in particular.

EC’s authority to regulate emissions from motor vehicles, and more generally to regulate air quality, stems from the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 ( CEPA ).

Alignment with Government Priorities and Departmental Strategic Outcomes

Finding 2: The CTI is aligned with federal priorities and departmental strategic outcomes.

The CTI is clearly aligned with the Government of Canada’s priorities and policy objectives. Budget 2011 espoused the Government’s commitment to the Copenhagen Accord and a balanced approach to emissions reduction. In Budget 2013, the Government of Canada again affirmed its Copenhagen commitment to reduce Canada’s total GHGs emissions by 17 percent from 2005 levels by 2020 and highlighted its sector-by-sector approach, of which the CTI is a part. In Budget 2012, 2013 and 2014, the Government of Canada announced various measures it had taken to promote investment in new technologies to reduce GHGs emissions, including technologies applicable to the transportation sector.

The initiatives are aligned with TC’s strategic outcome of a “Clean Transportation System,” but also contribute to the achievement of a “Safe Transportation System” and an “Efficient Transportation System. ” EC’s initiatives are aligned with the strategic outcome of “Threats to Canadians and their environment from pollution are minimized. ”

Continuing Need

Finding 3: CTI supports efforts to meet international obligations and continental commitments to address the problem of GHGs and air pollutants from transportation.

Regarding GHGs : In 2010, Canada made commitments under the Cancun Agreements, which repeated the target agreed to under the Copenhagen Accord in 2009, to reduce total GHGs emissions to 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020. The transportation sector is a major emitter of GHGs . In 2005, transportation was the largest source of such emissions in Canada (26 percent). This was still the case in 2011, with transportation accounting for 25 percent of GHGs emissions.

Figure 1: Historical and Projected Trends in GHGs Emissions in Canada (MT of CO2e)Footnote 2, 1999-2020

Source: Canada’s Emissions Trends, 2013, Environment Canada.

Figure 1: Historical and Projected Trends in GHGs Emissions in Canada (MT of CO2e), 1999-2020

Figure 1 shows the historical trend in GHGs (megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents) starting in 1990 and projected out to 2020. GHG has steadily increased from 1990 (when it was less than 600 Mts) by almost 50 Mts per 5 year period (peaking at almost 750 Mts around 2005). Without implementing government measures, it is predicted that GHG levels will continue to rise, reaching 862 Mts by 2020. With current government measures, in place as of May 2013, it is predicted that GHG levels will instead reach approximately 734 Mts by 2020 (a reduction of 128 Mts when compared to expected levels, if government measures were not taken), resulting in a deficit of 122 Mts if Canada is to meet its Copenhagen commitments at 612 Mts.

With provincial and federal measures in place as of May 2013, emissions are projected to be 734 megatonnes ( Mt ) by 2020, or 122 MtFootnote 3 higher than Canada’s target of 612 Mt, established through the Cancun/Copenhagen commitments (see Figure 1). Footnote 4 However, as EC’s Canada’s Emissions Trends, 2013, notes, “significant progress” has been achieved and emissions would have risen to 862 Mt if no action had been taken by consumers, businesses and governments since 2005.

Both the oil and gas industry (mostly export) and the transportation sector were major contributors to the increase in GHGs emissions between 1990 and 2011. The increase in the amount of emissions can be attributed to growth in oil sands production and the increase in road freight movement, as well as a large increase in the number of motor vehicles, especially light-duty gasoline trucks (vans, Sport Utility Vehicles and pickups) and heavy-duty diesel vehicles (commercial transport trucks) on the road. Between 1990 and 2011, total transportation-related emissions grew by 33 percent, with heavy-duty vehicle emissions growing by 84 percent, followed by light-duty vehicles at 26 percent, marine transportation at 21 percent and otherFootnote 5 at 6 percent. Domestic aviation decreased by 15 percent and rail emissions fell by 1 percent over this same period. Footnote 6

GHG emissions from transportation are projected to increase between 2011 and 2020 (see Figure 2), due largely to expected increases in emissions from freight transportation, which is in turn due to expected increases in economic activity (e.g. number of freight kilometres travelled) and population growth.

Figure 2: Trends in GHGs Emissions from Transportation, 1990-2020 (Mt of CO2e)

Source: Canada’s Emissions Trends, 2013, Environment Canada.

Figure 2: Trends in GHGs Emissions from Transportation, 1990-2020 (Mt of CO2e)

Figure 2 shows the trend in GHG emissions (megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents) from transportation starting in 1990 and projected to 2020. GHG levels rose from 128 Mts in 1990 to 167 Mts in 2005 (where it plateaus until 2010). GHG emissions have begun to rise once again. Levels have reached 170 Mts in 2011 and are expected to continue rising slowly, reaching 176 Mts by year 2020.

Between 2011 and 2020, freight-related GHGs emissions from the marine mode are expected to increase by 29 percent, from aviation by 22 percent, from road by 13 percent and from rail by 13 percent.

Although overall GHGs emissions are expected to grow in the freight sector, they are expected to decrease relative to business-as-usual levels as a result of various federal, provincial and territorial initiatives. For example, the heavy-duty vehicle regulations announced in 2013 are expected to improve the average fuel efficiency of trucks from 2.5 litres/100 tonne-km to 2.1 litres/100 tonne-km by 2020. Also, over the same time period, total emissions from light-duty vehicles ( LDVs ) are forecast to decline by 7 percent, mainly as a result of the implementation of the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emissions Regulations for model years 2011 to 2016, and the Renewable Fuels Regulations. Footnote 7 This will help counterbalance some of the growth in emissions from transportation.

The consumption of fossil fuels by the transportation sector is expected to increase into the foreseeable future (see Figure 3), although the consumption of gasoline will flatten, reflecting the trend in GHGs emissions from LDVs .

Figure 3: Energy Consumption Trends in Canada, 2000-2035 (in Petajoules)

Figure 3: Energy Consumption Trends in Canada, 2000-2035 (in Petajoules)

Figure 3 shows trends for five fuel types (all carbon-based fuels, minus cleaner CB fuels, motor gasoline, diesel, and aviation fuel) starting in 2000 and projected into 2035. Generally, consumption of almost all fuel types is expected to increase. All carbon-based fuels and minus cleaner CB fuels have the highest consumption rates. Both fuels are expected to increase from almost 2,250 petajoules in 2000 to approximately 3,500 and 3,000 petajoules in 2035, respectively. Diesel is expected to increase from almost 750 to 1,250 petajoules while aviation fuel, with the lowest consumption rate, increases only slightly (averaging around 250 petajoules). Motor gasoline is the sole exception to the increasing trend. Levels rose from approximately 1,250 petajoules in 2000 to peak around 1,500 in 2010. However, motor gasoline is predicted to decline to levels rivaling its original consumption rate in 2000 by 2035 because of the introduction of new energy efficient standards in on-road vehicles.

While various measures put in place by all levels of government have slowed the increase in the amount of GHGs in the atmosphere (and emitted from the transportation sector) relative to what the amount would have otherwise been, the amount of GHGs continues to increase. This means that there is a GHGs reduction deficit, and that the challenge of reducing the absolute level of GHGs emissions in general, and from transportation in particular, is a long-term one.

Regarding Air Pollutants: The Government of Canada made commitments to reduce air pollutants from transportation in its 2007 Regulatory Framework for Air Emissions and to collaborate with international partners and governing bodies to which Canada is a signatory (e.g. IMO and ICAO ) to develop regulations to reduce pollutants from transportation.

Table 4: Contribution of the Transportation Sector to Air Pollutant Emissions, 1990-2012 (Kilotonnes)

| Pollutant and Transportation Mode | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2012 | Average Annual % Growth Rate (1990-2012) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Monoxide ( CO ), of which | 14,176 | 12,826 | 11,248 | 9,662 | 8,704 | 8,163 | -2.5 |

| Total Transportation-Related Emissions | 11,742 | 10,274 | 8,868 | 7,097 | 6,515 | 6,023 | -3. 0 |

| Light-Duty Vehicles | 8,726 | 7,506 | 6,169 | 4,197 | 3,518 | 3,104 | -4. 6 |

| Heavy-Duty Vehicles | 824 | 367 | 238 | 192 | 120 | 95 | -9. 3 |

| Aviation, Marine & Rail Transportation | 106 | 94 | 92 | 86 | 93 | 95 | -0.5 |

| Off-Road Equipment, Tire Wear & Brake Lining | 2,086 | 2,307 | 2,370 | 2,622 | 2,784 | 2,728 | 1.2 |

| Nitrous Oxide (NOx), of which | 2,534 | 2,525 | 2,598 | 2,398 | 2,056 | 1,850 | -1.4 |

| Total Transportation-Related Emissions | 1,556 | 1,486 | 1,381 | 1,263 | 1,138 | 994 | -2. 0 |

| Light-Duty Vehicles | 552 | 425 | 329 | 226 | 175 | 146 | -5.9 |

| Heavy-Duty Vehicles | 317 | 349 | 339 | 303 | 208 | 162 | -3. 0 |

| Aviation, Marine & Rail Transportation | 301 | 282 | 271 | 294 | 297 | 300 | 0. 0 |

| Off-Road Equipment, Tire Wear & Brake Lining | 387 | 430 | 442 | 439 | 458 | 386 | 0. 0 |

| Volatile Organic Compounds ( VOC ), of which | 2,403 | 2,339 | 2,255 | 2,027 | 1,764 | 1,755 | -1.4 |

| Total Transportation-Related Emissions | 985 | 860 | 745 | 592 | 491 | 440 | -3. 6 |

| Light-Duty Vehicles | 616 | 496 | 398 | 255 | 192 | 154 | -6.1 |

| Heavy-Duty Vehicles | 59 | 31 | 22 | 19 | 15 | 13 | -6. 6 |

| Aviation, Marine & Rail Transportation | 15 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 1.1 |

| Off-Road Equipment, Tire Wear & Brake Lining | 294 | 318 | 310 | 301 | 266 | 253 | -0. 7 |

| Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5), of which | 466 | 416 | 381 | 346 | 252 | 269 | -2.5 |

| Total Transportation-Related Emissions | 94 | 88 | 75 | 68 | 61 | 56 | -2. 3 |

| Light-Duty Vehicles | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | -5. 6 |

| Heavy-Duty Vehicles | 18 | 15 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 3 | -7. 7 |

| Aviation, Marine & Rail Transportation | 14 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 0.2 |

| Off-Road Equipment, Tire Wear & Brake Lining | 57 | 57 | 52 | 45 | 41 | 36 | -2.1 |

| Sulphur Oxide ( SOx ), of which | 3,097 | 2,565 | 2,361 | 2,185 | 1,358 | 1,265 | -4. 0 |

| Total Transportation-Related Emissions | 182 | 150 | 122 | 110 | 95 | 97 | -2. 8 |

| Light-Duty Vehicles | 13 | 16 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 1 | -9. 3 |

| Heavy-Duty Vehicles | 22 | 15 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | -14. 3 |

| Aviation, Marine & Rail Transportation | 123 | 99 | 87 | 86 | 92 | 94 | -1.2 |

| Off-Road Equipment, Tire Wear & Brake Lining | 24 | 21 | 15 | 17 | 0 | 0 | -17. 3 |

Source: Environment Canada, National Pollutant Release Inventory.

The transportation sector is also a major emitter of pollutants. Excluding emissions from open and natural sources, the transportation sector accounted for 75 percent of total carbon monoxide ( CO ) emissions, 54 percent of nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, 27 percent of volatile organic compounds emissions, 24 percent of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions and 7 percent of sulphur oxide (SOx) emissions in 2011 (see Table 4). It also accounts for 25 percent of lead emissions.

Given the transportation sector’s significant share of pollutant and GHGs emissions; the projected growth in GHGs emissions and the use of fossil fuels; the projected 122 Mt shortfall in meeting Copenhagen/Cancun commitments; and Canada’s international regulatory obligations and commitments, there is clearly a need for ongoing initiatives that reduce emissions from the transportation sector, especially for HDVs and the marine, rail and aviation modes.

Finding 4: The Clean Transportation initiatives support the approach outlined by the Government of Canada regarding action on climate change and the Clean Air Agenda.

A review of the suite of initiatives under the CTI resulted in the finding that the CTI is in-line with the balanced approach put forward by the Government of Canada. The Government’s approach is to encourage strong economic growth and job creation while achieving environmental objectives. The Government of Canada is following a sector-by-sector approach to regulatory development, which will lower emissions where it makes sense to do so, and will seek out the lowest-cost solutions first before proceeding to implement more costly measures.

The overall objective of the CTI is to decrease emissions intensity through the adoption of new practices and technologies in the transportation sector. This is expected to result in a reduction in the growth of emissions due to the growth of the population and economy, and in turn, the increased use of the transportation system. Eventually, the growth in absolute emission levels is expected to decrease.

The initiatives are using three major vehicles to contribute to this objective: regulatory changes, voluntary measures by industry and financial support for the implementation of new and more efficient technologies.

Changes to regulatory frameworks

The changes to regulatory frameworksbeing made through the initiatives align with Canada’s international obligations and commitments regarding the reduction of emissions and the Government of Canada’s 2007 Regulatory Framework for Air Emissions. These obligations and commitments require collaboration with the International Maritime Organization ( IMO ), the International Civil Aviation Organization ( ICAO ), the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council ( RCC ) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, among others, in pursuing regulatory change. The purpose of this collaboration, however, is not simply alignment, but also to ensure that Canadian needs and interests are taken into account.

Voluntary measures complement the implementation of new regulations

Agreements with industry associations representing the aviation and the rail sectors promote voluntary measures to improve fuel efficiency, and in the case of the rail sector, to reduce criteria air contaminant ( CAC ) emissions. Footnote 8

The rail memorandum of understanding (MOU) serves as a bridge to the proposed Locomotive Emission Regulations, which will introduce new emission standards for CACs and which will align with those in the U.S. There will still be a need for a rail MOU even after the proposed Regulations are in place because the regulations would only apply to federally regulated railways and would also not cover GHGs . In addition, Canada and the US are presently working on a Canada- U.S. Voluntary Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Locomotives through the RCC .

The aviation action plan (Canada’s Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gases from Aviation) is an ICAO -recommended voluntary initiative for member states to contribute to ICAO’s global GHGs reduction goals. It sets an aspirational goal for Canada to improve aviation fuel efficiency by an annual average of 2 percent per year by 2020, from the 2005 baseline, and it supports ICAO’s long-term goal of global carbon neutral growth from 2020 onwards and absolute GHGs emission reductions by 2050.

The implementation of new technologies

The reduction of GHGs and pollutant emissions from transportation is dependent on technological advancements in transportation and the implementation of those technologies. TC has been exercising leadership in facilitating the implementation of new technologies at Canadian ports through contribution funds. The rationale for a federal monetary incentive to install shore power at Canadian ports through the Shore Power Technology for Ports ( SPTP ) Program is the high capital cost of the installations and industry’s lack of experience with the technologies. In the case of the Truck Reservation System Program (TRSP), federal leadership was needed to ensure compatibility in the types of systems being installed in and across Canadian ports. Further, similar government-funded programs are available in the U.S. at the federal or state levels and the two contribution programs have the potential to produce immediate results in terms of emissions reductions.

{ ATIP Removed }

Scientific, technological and research support

The testing and evaluation of new and emerging technologies; R&D ; and policy and socio-economic research, data development and modeling; are activities that are important to ensuring the advancement of the regulatory process and/or the development of non-regulatory environmental and performance codes, standards and test protocols, into the foreseeable future. These advancements are in turn important to the introduction of new clean technologies that are safe and effective.

These activities are also important to the alignment of national, continental and international standards while minimizing the impact on industry’s productivity or competitiveness. These types of activities are generally not carried out by the private sector. Industry testing and R&D are not undertaken to support regulatory work, but rather to support product development and to demonstrate that their products conform to existing regulations.

Nonetheless, TC has played a leadership role in acquiring private sector investment to undertake evaluation and testing, and R&D that meets its regulatory needs. Furthermore, TC’s legislative mandate specifically requires the use of R&D: the Aeronautics Act (4.2 d); the Railway Safety Act (14 (1)a); the Motor Vehicle Safety Act (20.1a) & b)); and the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act (25.(a)). Other Acts imply the need for TC to use R&D, such as the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act and the Canada Transportation Act. In addition, participation in international organizations such as the IMO and the ICAO often requires carrying out R&D activities.

Evaluation Findings: Performance

The performance of the CTI was assessed by examining the extent to which the initiatives were being delivered as planned, as outlined in foundational documents. Results achieved by the regulatory initiatives and the contribution programs, which committed to deliver emission reductions, were measured against emission reduction targets. Results were also measured in relation to the performance indicators outlined in the Performance Measurement Strategy for the overall initiative.

Implementation

To assess how effectively the initiatives were being implemented, the evaluation first compared planned and actual expenditures and then assessed the extent to which the deliverables were being generated as planned.

Planned versus actual expenditures

Finding 5: The difference between the amount allotted and the amount spent over the first three years of the CTI is small for the regulatory initiatives and eTV II , and where larger, can be explained by factors outside of departmental control.

Over the first three fiscal years of the CTI , TC was allotted $76.1 million and spent $55. 6 million or 73 percent (see Table 5). Excluding the two contribution programs and the Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative, TC spent 84 percent of the monies allotted.

On the one hand, the timing of the approval of the authorities to deliver the initiatives (September 2011) resulted in a “short” 2011-2012 fiscal year and made it difficult to solicit and finalize contracts, especially for the research elements of the initiatives. As a result, portions of the monies allotted in the first year were re-profiled into the 2012-2013 fiscal year, and not always totally spent then, either. On the other hand, many more dollars than reported in Table 3 had been committed by 2013-14 for these initiatives (but not included in the financial data), given that many of the projects carried out under them are multi-year (e.g. R&D ). Regarding the latter, a majority of the R&D monies allotted for the aviation, rail, marine and support for vehicle greenhouse gas emission regulations initiatives for the five years had already been spent or committed, and in the case of the latter three initiatives, over two-thirds of the allotted funds had been spent.

The lower “percentage spent” for the Rail Sector Regulatory Initiative is explainable by the delays in the proposed Locomotive Emission Regulations, which have also held-up capital expenditures for the Locomotive Emissions Information System ( LEIS ). In addition, TC decided to pursue a voluntary approach to GHGs reduction in the rail sector with the U.S. , rather than a regulatory one, as was initially planned.

As for Environment Canada’s Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative, the lower “percentage spent” can be attributed to monies not spent in the first year of the initiative due to the Department being under Governor General Warrants for more than half of that year and funds not spent in year two and three due to constraints on hiring and spending under Budget 2012.

Table 5: Percentage of Allotted Money Spent by Initiative

| Initiative | Total $ Allocated

(2011-12 to 2013-14)* |

Total $ Spent

(2011-12 to 2013-14)* |

% Spent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aviation Sector Regulatory Initiative | 8,053,431 | 6,768,218 | 84% |

| Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative (TC) | 13,098,387 | 11,943,458 | 91% |

| Rail Sector Regulatory Initiative | 8,784,330** | 5,874,286 | 67% |

| Support for Vehicle GHGs Emission Regulations | 6,122,033 | 5,682,762 | 93% |

| ecoTECHNOLOGY for Vehicles II Program | 21,904,746 | 18,193,853 | 83% |

| Total | 58,642,946 | 48,462,577 | 84% |

| Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative | 971,620 | 414,814 | 43% |

| Truck Reservation Systems Program | 3,790,248*** | 898,330 | 24% |

| Shore Power Technology for Ports Program | 11,999,954 | 5,872,741 | 49% |

| Total | 76,129,750 | 55,648,462 | 73% |

| Marine Sector Regulatory Initiative (EC) | 6,482,894 | 3,659,059 | 56% |

| Grand Total | 82,612,662 | 59,307,521 | 72% |

| *To make the data comparable, these numbers exclude PWGSC amounts for fiscal year 2013-2014 from both allocated and spent figures because the evaluators were not provided with PWGSC amounts for this year for the amount spent. **Subtracted from the 2013-14 amount, $650,000 of capital that was re-profiled from 2012-13, to avoid it being double-counted. ***Subtracted from the 2013-14 data, $725,000 of Grants and Contribution money that was re-profiled from 2012-13, to avoid it being double-counted. | |||

The low “percentage spent” on the Gateway Carbon Footprint Initiative (43 percent) is due largely to using in-house resources to complete various phases of the project rather than using contractors, as was initially planned.

Finding 6: The use of allocated funding by the contribution programs has been slower than expected due to delays in negotiations, the contracting process and/or project completion.

TC has spent approximately half of the $12 million allotted for the first three years of the Shore Power Technology for Ports (SPTP) Program. However, the SPTP Program has managed to secure additional interest and approvals in the fourth fiscal year of the program such that under the best case scenario (as of November 2014), about $23.4 million of the 27.2 million available contribution monies for the five-year period will be spent by the end of the program.

A major reason for the slower than anticipated take-up of funds is delays in the implementation of two Quebec projects due to the provincial election; the April 2014 election has caused delays in getting the financial participation of the Ministère des Transports du Québec and Hydro-Quebec to complete the projects’ financial plans. An additional contributing factor is the complexity of the projects – installations have to be custom made, preliminary environmental reviews are conducted for each project, engineering reports are required and recipients often have to pull together large sums of money.

TC has used approximately 24 percent of the $3.8 million allotted for the first three years of the TRSP . The timing of the approval of the Program’s terms and conditions in the 2011-2012 fiscal year made it difficult to solicit and finalize contracts in the first fiscal year. Also a number of adjustments were made within the TRSP due to delays in negotiating agreements with recipients and/or completing the contracting process with partners. Such delays caused two signed projects to be moved to 2014-15. There have also been delays in completing projects (e.g. the Common Data Interface and Pre-Gate Concept of Operations project). However, by October 2014, the TRSP had committed 86% of the funds allotted for the five years of the Program.

Implementation of New or Amended Regulatory Frameworks

Finding 7: For the most part, TC has delivered the new or amended regulatory frameworks with diligence. However, changes to the rail and aviation regulatory frameworks and to the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act have not yet been implemented due to circumstances outside of departmental control. { ATIP Removed }.

Under the Aviation Sector Regulatory Initiative, TC planned to deliver new or amended emission regulatory frameworks for the Canadian aviation sector, including new oxides of nitrogen emission standards for new aircraft engines that were expected to reduce these emissions by 15 percent, starting in 2013. TC proceeded to incorporate by reference, the ICAO oxides of nitrogen standards, into the Canadian Aviation Regulations. At the time of the evaluation, TC’s work had been completed and any further steps toward implementation were outside of TC’s control. No other work on standards, codes or guidelines was concluded by ICAO over the time frame of the initiative that would require a regulatory response in Canada.

TC has provided substantial input on behalf of the work being carried out at the ICAO . The metric system and draft certification requirement for carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions were approved by ICAO in 2013-14. As a result, work has been initiated at ICAO to set the regulatory limit and applicability. The final CO2 standard for airplanes is expected for 2016. Also, a draft Aerospace Recommended Practice ( ARP ) is being developed by the SAE International’s Aviation Engine Emissions Measurement Committee SAE-31, a major step in the development of the certification requirement for ICAO’s non-volatile particulate matter ( nvPM ) mass and number standard for aircraft engines. The draft ARP is expected to be finalized by early 2015. The new nvPM standard is expected for 2016.

As part of the Marine Sector Regulatory Initiatives, TC was expected to implement new air pollutant emission regulations under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 to reduce sulphur oxide emissions by up to 94 percent and nitrogen oxide emissions by up to 80 percent by 2020. Building on the outcomes of negotiations at the IMO, TC proceeded to amend the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations. They were published under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 on May 8, 2013. The Regulations implement the following:

- Standards of the North American Emission Control Area ( NA ECA ) for sulphur and nitrogen oxides;

- Updated global fuel quality standards to limit the emission of oxides of sulphur from ships operating in waters outside of the NA ECA ;

- Fuel quality standards to limit the emission of oxides of sulphur from ships operating in the Great Lakes and St Lawrence waters (fleet averaging for domestic vessels until 2020, at which point the NA ECA standard will apply);

- Updated standards for oxides of nitrogen emissions from ships (applies to some existing ships and all newly built ships);

- Updated standards to control emissions of volatile organic compounds (cargo vapours);

- Updated standards to control ozone depleting substances;

- Aligning emissions requirements for medium-sized marine engines with the U.S. standards – known as Category 2 engines;

- Applying the energy efficiency design index to newly built ships on international voyages; and

- Requiring all large commercial ships to maintain an energy efficiency management plan.

Although the Regulations were implemented nine months later than planned, TC implemented interim measures to bridge the gap between the date the Regulations were supposed to be in place and the date they were actually put in place. The delay was due to the need for additional consultations with the domestic industry, who would be operating 100 percent of the time inside the ECA , while most international vessels would be operating inside it for less than 10 percent of their time (depending on the route). As well, there was a need to give extensive additional consideration to the impacts the amended Regulations would have had on the cruise sector, for which governments had committed considerable investments. This was subsequently addressed with alternative compliance options, developed in consultation with the cruise sector and US agencies.

EC published the Regulations Amending the Sulphur in Diesel Fuel Regulations under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 ( CEPA ) on July 4, 2012, only one month later than planned. The regulations limit the sulphur content in the production, import and sale of diesel fuel for use in large ships to 1,000 ppm, aligning standards with the U.S. ’s Clean Air Act. The standards complement the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations and also enable the implementation of the NA ECA by ensuring that fuel suppliers can provide low-sulphur fuel to marine vessels. EC continues to monitor the quality of marine fuel.

EC has also drafted instructions for a regulation to align emission standards for small marine diesel engines with those of the United States. { ATIP Removed } EC is updating the emissions inventory it created for the small diesel sector with more recent importation data.

Also, TC developed an informal reciprocity agreement with the United States on the regulation of air pollutant emissions in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Region.

{ ATIP Removed }

Through the RCC Locomotives Emissions Initiative, TC has also commissioned the NRC , in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, to produce the now-completed technology and infrastructure scan, “Reducing Emissions in the Rail Sector: Technology and Infrastructure Scan and Analysis. ” The purpose of the scan was to identify opportunities to reduce GHGs from the rail sector. This scan formed the basis of discussion at the 2012 Railroad Workshop: Working Together to Reduce Locomotive Emissions, which was held in Urbana, Illinois, in October 2012 and was co-hosted with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The Support for Vehicle Green House Gas Emission Regulations Initiative committed to deliver new regulations expected to reduce heavy-duty vehicle ( HDV ) GHGs emissions by approximately two megatonnes ( Mt ) per year by 2020. EC implemented the Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations in February of 2013 for model years 2014-2018, under the CEPA . These regulations align with standards in the U.S. A Notice of Intent was published on October 4, 2014 in the Canada Gazette, Part I, indicating the Government of Canada’s intent to develop proposed regulations to further reduce GHGs emissions from on-road heavy-duty vehicles and engines for post-2018 model years. These proposed regulations would build on the current regulations.

EC implemented the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations in the fall of 2010 for model years 2011-2016. EC has made amendments to these Regulations for model years 2017-2025, extending the regulatory approach that sets emission standards for light-duty vehicles (LDVs) for model years 2011-2016. The final Regulations for model years 2017-2025 were published inthe Canada Gazette, Part II, on October 8, 2014.

TC has been providing support for these regulations through the eTV II Program and the Support for Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations Initiative. This support includes possible changes to the vehicle safety regulations. For example, the introduction of electric and hybrid vehicles has brought to light a number of safety issues concerning battery safety and safety concerns for pedestrians and the blind or visually impaired (because these vehicles are typically quiet at low speeds). The push for fuel economy also raised the issue of the safety of low-rolling resistance tires for heavy trucks (specifically, the traction of these tires in snowy or wet conditions). Hydrogen, expected to be the fuel of choice for fuel cell vehicles, also raises potential safety issues because it has very wide flammability limits when mixed with air. Testing under the eTV II Program has provided the Department with much of the regulatory safety information needed to address these issues.

At the time of the evaluation, TC ’s Motor Vehicle Safety group was preparing a Canada Gazette, Part I, proposal to update the Canadian regulatory requirements for both propane and natural gas vehicle safety under the Motor Vehicle Safety Act ( MVSA ). TC is also working towards determining the need to update the current Canadian/ U.S. regulations regarding electric vehicle safety to include new testing requirements for battery safety and overall electric vehicle safety, including minimum noise requirements for quiet vehicles. Work on electric vehicle safety and minimum noise regulations, undertaken by eTV II and TC’s Motor Vehicle Safety group comprised a key component of the Canada- U.S. RCC work-plan on motor vehicle regulations, and has supported on-going efforts to ensure that new or amended vehicle regulations are aligned, where appropriate, to eliminate or reduce barriers to trade and consumers’ access to new clean technologies.

Further, changes were made to the MVSA in the summer of 2014 that should result in a more efficient operating environment for stakeholders, regulated industries, and TC , as well as for Canadians. The revised Act now includes:

- An expanded ability to incorporate by reference, regulations and standards developed by other organizations, such as the U.S. government and the International Organization of Standardization;

- Removal of the requirement that regulations that incorporate Technical Standards Documents must expire after five years; and

- Removal of the requirement for mandatory Canada Gazette, Part I, pre-publication.

This will streamline the ability to implement any new or amended regulations, aligned to the fullest extent possible with the U.S. , which will help eliminate barriers to the introduction of new clean technologies.

Implementation of Compliance Regimes

For some of the regulatory initiatives, TC committed to implementing or updating its compliance regimes to ensure that the required changes defined in the new or amended regulatory frameworks are implemented by industry.

Finding 8: Two compliance regimes have been implemented or updated following the amendments to the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations and the Sulphur in Diesel Fuel Regulations. A compliance regime to accompany the proposed Locomotive Emissions Regulations is also likely to be fully operational by the end of the initiative, if the proposed Regulations are implemented in 2015, or shortly thereafter.

TC has undertaken a variety of compliance activities in support of the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations (e.g. manuals, inspector training, operational policies, guidelines to support the regulations, and communications products to inform the marine industry in Canada). Inspections are already taking place and no compliance issues have been reported to date. Marine Safety is presently preparing for January 1, 2015, when the stricter 0.1 percent sulphur content in marine fuel standards for vessels comes into effect.

EC is using the existing compliance regime for engaging in compliance and enforcement activities for the Sulphur in Diesel Fuel Regulations. They have provided information sessions on regulatory updates (webinars and face-to-face); an annual compliance promotion package for fuels to all regulated parties; compliance verification (review of annual reports and follow up) and other support to enforcement officers; and published reports on data received as a result of the reporting requirements of industry under the Regulations. Enforcement activities have been undertaken by EC’s Enforcement Branch, in accordance with EC’s Compliance and Enforcement Policy.

TC has completed Phase I of the LEIS that will collect data submitted by the railway companies to help assess compliance with the proposed Locomotive Emission Regulations and track and report on emission reductions.

{ ATIP Removed }

There is no need for a compliance regime for any regulatory changes made under the Aeronautics Act or the Motor Vehicle Safety Act since the regulations are enforced through certification, prior to the aircraft, aircraft engines or vehicles entering the market.

Implementation of Voluntary Agreements

Finding 9: TC has successfully negotiated the two planned voluntary agreements with industry to increase fuel efficiency and reduce GHGs emissions and/or CAC emissions intensity.

As planned, two sector-wide voluntary agreements with industry have been implemented. Canada’s Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gases from Aviation has been finalized and published, and the first annual report for the 2012 calendar year under the Action Plan was published in 2013. Footnote 9

A renewed MOU was negotiated and signed with the Railway Association of Canada ( RAC ) on April 30, 2013,Footnote 10 and the RAC published its first annual report under the new Locomotive Emissions Monitoring Program ( LEM ) in April 2014.

Implementation of New Technologies

Finding 10: TC has contributed to the implementation of emissions reduction technologies at Canadian ports through the Shore Power Technology for Ports ( SPTP ) Program and the Truck Reservation System Program (TRSP).

At the time of the evaluation, the SPTP Program had completed two projects - Seaspan Ferries at the Swartz Bay Terminal and Port Metro Vancouver ( PMV ). Two more projects have been signed and are under way (Port of Halifax and BC Ferries) { ATIP Removed }. There are a total of 15 berths covered by signed or completed agreements, with the possibility of { ATIP Removed } being added. Based on a review of the two reports provided by recipients, evaluators concluded that the projects were likely to broaden the understanding of shore power facilities and produce lessons learned from the installation of these technologies. However, it was not clear that all of the planned projects will be completed by the planned end of the five-year program.

The TRSP has completed three projects at PMV (the Container Drayage Truck Efficiency Project Expansion, the Common Data Interface System, and the Foundational Study – Phase II Drayage Model). Two more projects have been signed and are underway (A project to Reduce Polluting Emissions at the Port of Montreal, and the Global Positioning System II – Container Drayage Truck Efficiency Program at the PMV ).

Implementation of Science and Technology Program

Finding 11: The science and technology program, consisting of R&D and evaluation and testing under the various initiatives, is being carried out as planned.

In support of regulatory and non-regulatory frameworks, 92 R&D or evaluation and testing projects have been initiated to examine the performance or safety of existing or new clean transportation technologies (e.g. natural gas use in marine vessels, emissions measurement for aircraft, alternative fuels for aircraft and trains, and the safety of electric vehicles). TC has spent or committed $22.1 million on these projects in the first three fiscal years. The majority of the R&D funds allotted under the various initiatives for the five-year period had been spent or committed by the end of 2013-14, since many of the R&D projects are multi-year.

In addition, TC has set-up the Clean Rail Academic Grant Program under the Rail Sector Regulatory Initiative. The Program provides up to ten $25,000 annual grants to academic research programs currently developing emission reduction technologies and practices for the transportation sector that could be applied to the rail industry. It has been implemented according to plan, and $500,000 has been spent in two funding rounds to advance scholarship in emission reduction technologies. Two more rounds will be held over the next two fiscal years.

Implementation of Socio-economic and Policy Research, Data Development and Modeling Program

Finding 12: The socio-economic and policy research, data development and modeling program under the various initiatives is, for the most part, being implemented as planned.

Evaluators found that some 35 socio-economic or policy research, data development or modeling projects had been initiated under the various initiatives, although what constitutes a project was not always clear. This is due to the evolving nature of some of the work and the fact that parts of the projects were often done in-house, with other parts undertaken by contractors. While evaluators were unable to obtain expenditure data for all of the projects undertaken on behalf of the initiatives, they counted $690,789 spent between 2011-12 and 2013-14 on such projects, with another $335,725 planned to be spent in 2014-15. To the extent the evaluators could match the studies undertaken with those to which TC committed, only one appears to have not been undertaken (an update to the Terminal Truck Reservation Study), one has been delayed (the fuel consumption survey) and one will only be undertaken if data can be found to do it (a carbon footprint for the Atlantic Gateway).

Early Results: Emission Reductions through Voluntary Agreements, Regulatory Frameworks and Contribution Agreements

It is too early to ascertain whether TC will meet the emission reduction targets expected as a result of the changes it has made to regulatory frameworks. However, there is some early evidence that some of the initiatives are having immediate impacts.

Finding 13: Progress is being made with the aviation industry adopting technologies and practices to achieve the objectives of Canada’s Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gases from Aviation.

The Action Plan includes objectives and targets such as reduced GHGs emissions intensity and increased fuel efficiency, respectively. The central performance measure of the Action Plan, litres of fuel consumed per 100 revenue tonne-kilometres (RTK),Footnote 11 fell from 37.80 to 37.16 between 2011 and 2012 (it was 40.43 in 2005). This represents a 1.7 percent increase in fuel efficiency for Canada’s aviation sector between 2011 and 2012, and the highest fuel efficiency reported in their annual report since 2005, which has been achieved by Canadian carriers replacing older aircrafts with more efficient ones, and making greater-use of performance-based navigation and surveillance technologies. While this is less than the 2 percent average annual target, past trends in fuel-efficiency improvement suggest it is possible for the aviation sector to reach their target by 2020 target.

As reported in the most recent annual report, GHGs intensity, measured according to fuel efficiency, would have decreased between 2011 and 2012 as a result of the increase in fuel efficiency.

Finding 14: Progress is being made with the rail industry adopting technologies and practices to achieve the intent of the MOU with the Railway Association of Canada (RAC), such as decreased fuel consumption, GHGs emission intensity and Criteria Air Contaminants (CACs) emissions.

As reported in the most recent LEM report available at the time of the evaluation, between 2010 and 2011 there was a decrease of 3. 3 percent in the fuel consumed by railway operations in Canada; this was achieved despite increases in freight traffic. The fuel consumed by railway operations in Canada decreased from 2,048.82 million litres in 2010 to 1,980.18 million litres in 2011. This decrease reflects the fuel reduction methods taken by member railways, which include an increased proportion of fuel efficient high-horsepower locomotives in the fleet and an optimization of in-train locomotive power with traffic weight.

Overall GHGs emission intensity for Class I freight decreased by 7.2 percent between 2010 and 2011, from 16.43 kg CO2e per 1,000 RTK to 15.24 kg CO2e per 1,000 RTK . The 2015 target is 15.45. Regional and short-line railways were also able to lower GHGs emission intensity by 2.2 percent, relative to 2010. Total GHGs emissions from all railway operations in 2011, expressed as CO2e, was 5,954.70 kilotonnes (kt), as compared to 6,156.82 kt in 2010 and 6,196.70 kt in 1990.

In terms of CACs, the rail industry has a good previous long-term track record in reducing CAC emissions from locomotives. All CACs from railway operations, especially NOx and SOx, have been declining since the early 2000s. For example, between 2010 and 2011, NOx emission intensity from all freight operations decreased to 0.25 kg per 1,000 RTK from 0.28 kg per 1,000 RTK (and from 0.52 kg per 1,000 RTK in 1990).

In addition, although the proposed Locomotive Emission Regulations have not yet been implemented, most of the locomotives purchased in Canada are from the U.S. and therefore already meet the U.S. standards with which Canada is aligning. Furthermore, the MOU with the RAC states that “until such time that new Canadian regulations to control CAC emissions are introduced, the RAC will encourage all of its members to continue to conform to US emission standards (Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations of the United States, Part 1033). ”

Finding 15: Although the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations were only recently implemented and their impact cannot be measured at this time, some aspects of the regulations would be having an immediate impact.

The requirement of a 1.0 percent sulphur content in the marine fuel used in large vessels will have had an immediate impact, with the greatest impact – reducing SOx emissions from all large vessels as of May 8, 2013 – likely to be a 40 percent to 60 percent reduction, since the typical heavy fuels used before the regulations had a 2.7 percent sulphur content for international vessels and a 1.9 percent sulphur content for domestic vessels.

The application of Tier II Nitrogen Oxide Standards will have had an immediate impact as well, but not as large, since it applies only to engines fitted to vessels after May 8, 2013. This approach applied to the 15 new lakers that were announced with deliveries between 2013 and the end of 2015, represents about a 20 percent reduction from the old Tier I standards.

Finding 16: There is early evidence that the Shore Power Technology for Ports ( SPTP ) Program and the Truck Reservation Systems Program (TRSP) are having their intended impacts on reducing GHGs emissions at Canadian Ports.