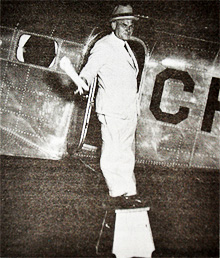

July 30, 1937: C.D. Howe, Minister of Transport, boarding the first cross-Canada “dawn to dusk” flight. The Department of Transport Lockheed 12 aircraft CF-CCT flew from Montreal to Vancouver.

"Many...services have been affected by the changes incident to reorganization, entailing in the case of certain branches removal to other quarters and the dislocation of established routine, as well as increase in duties. "

Sound familiar? These words actually were written almost 75 years ago to describe the difficulties encountered by management and staff of the new Department of Transport during its first year of operation. Changing the size, shape and mandate of government organizations apparently was a major challenge even then.

With the indomitable C.D. Howe at the helm, however, the job was done and, in 1936, the long‑established departments of Marine and Railways and Canals, along with the civil aviation branch of the Department of National Defence, were brought together under one federal government roof to form the Department of Transport.

Wartime efforts (by modes)

By August 1937, the Department of Transport had 6,543 employees on its roster, with an average monthly salary of about $85. Within two years, the department would be called upon to make a massive contribution to Canada's war effort.

The outbreak of hostilities in September 1939 had an immediate impact on the activities of the department's civil aviation division, which was tasked with building airports and training schools for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. By 1941, the division had completed 75 training sites and, at the end of the Second World War, 149 new airports had been built and 73 existing facilities expanded.

The department's meteorological division was equally challenged to meet the huge demands placed upon it during the war. The division not only supplied weather forecasts for civil aviation, air and naval forces and for agriculture, which was so vital to the war effort, it also trained hundreds of meteorology instructors for the Commonwealth air training plan schools.

Another herculean wartime task assigned to the Department of Transport was carried out by the Merchant Seamen Branch, which was set up in the early years of the war to recruit, train and house officers and crew for Canada's wartime Merchant Navy fleet. Thousands of recruits passed through its staffing pools and training schools. By 1945, 200 Canadian‑registered merchant ships were staffed entirely by more than 18,000 personnel recruited and trained by the branch. The branch director was able to report that, throughout the war years, "no ship ever missed a convoy or failed to sail on time for lack of crew or replacements."

Because of the enormous increase in the movement of freight by rail during the war, a Transport Controller was appointed within the department to coordinate this vitally important sector of the transportation system. The railways carried 90 per cent of Canada's wartime cargo, nearly tripling their pre‑war volume. By 1941, arrangements had to be made for the purchase of more than $22 million worth of locomotives and cars that were urgently needed by the Canadian National Railway to keep war materials and troops moving to coastal ports.

The radio division of the Department of Transport was also deeply involved in the war effort, developing and providing the radio aids to navigation needed to support air and marine transport, including the famous Atlantic Ferry Command that supplied desperately needed planes for Europe.

The day-to-day

A lesser known wartime activity was carried out by department's Dominion Lighthouse Depot at Prescott, Ont., which had been established at the turn of the century to produce and maintain marine aids to navigation. The depot was pressed into action early in the war to manufacture such materials as depth charges, casings and firing targets. By 1945, it had been transformed into a large, industrial organization with more than 700 employees.

In addition to the wartime achievements of the department's operational sectors, its administrative units also made a huge contribution. With minimal staffing and generally poor accommodations, they managed to keep up with the exceptional demands made upon them.

At the end of hostilities, things changed to peacetime mode rather quickly. The department turned its attention to upgrading facilities and equipment and to building a modern national transportation system on the greatly improved air, rail and marine infrastructure that was the legacy of the war.