July 2019

Evaluation report outlining results of the assessment of the Safety Management Systems (SMS) in Civil Aviation at Transport Canada as well as management’s action plan in response to recommendations identified in the evaluation.

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Evaluation of Safety Management Systems in Civil Aviation

- Evaluation Findings

- Appendix A: Transport Canada SMS Requirements

- Appendix B: References

- Appendix C: List of Recommendations

- Appendix D: List of Findings

- Appendix E: Management Action Plan

- Appendix F: Survey Questions

- Appendix G: Interview Questions

- Appendix H: List of Acronyms

Executive Summary

Since 2008, airline operators, private operators, approved maintenance organizations that service airline operator aircraft, air navigation services, and aerodromes/airports/heliports are required by Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) to have a Safety Management System (SMS) in place.

SMS is a documented process for managing risks that integrates operations and technical systems with the management of financial and human resources to ensure aviation safety or the safety of the public. The overarching intent of SMS regulations is for an SMS to become part of the culture of an organization and everyday work.

Transport Canada’s Evaluation and Advisory Services conducted an evaluation of SMS in Civil Aviation in 2017-2018 in order to answer two key questions: after 10 years of implementation, what has been the impact of SMS on aviation safety, and what lessons were learned from SMS roll out and implementation? We also conducted prospective analysis about the scalability of SMS.

The evaluation findings are based on multiple lines of evidence, including a survey of nearly 1800 industry stakeholders, case studies involving eight enterprises, more than 40 interviews and extensive document and literature review.

What we found

SMS Impact on Aviation Safety in Canada

Our evaluation found that:

- - A number of organizations have in place traits and practices that are indicative of an effective SMS, specifically in the areas of non-punitive reporting, executive commitment, and hazard identification and mitigation.

- - In those organizations a more systematic and documented way of identifying and addressing aviation risks is taking hold.

- - There is notable buy-in to SMS, in particular amongst large organizations.

- - Finally, we noted significant research evidence showing a correlation between SMS and improved safety performance.

Taken together, these suggest a positive impact of SMS on aviation safety in Canada over the last 10 years. However, due in part to data limitations, it was not possible to statistically attribute the extent of SMS’s contribution to aviation safety improvement.

SMS for Smaller Operators

SMS regulatory requirements have yet to be extended to most small operators in Canada. In this evaluation we inquired the extent to which SMS was scalable, that is, it could be adopted by a civil aviation organization regardless of the size of the organization. The majority of interview respondents believed that SMS would be useful to any size organization. Our survey and interviews showed that ‘documentation burden’; ‘cost considerations’; ‘training, awareness and competence’; and ‘lack of perceived benefits of SMS’ were key factors when thinking about SMS in smaller organizations.

In considering SMS scalability, TC should consider lessons learned from the initial roll-out in 2008. These are:

- - Provide more effective, clear and consistent guidance, both through TC materials and the interactions of inspectors with organizations.

- - Communicate well why having an SMS is better and why the cost is justified and that TC will deliver on providing effective support and guidance.

- - Conduct robust analysis of resource implications on TC of extending SMS to smaller organizations.

- - Ensure sufficient resources are available to maintain an adequate (however that is defined) level of ongoing oversight.

SMS Implementation

The evaluation examined how implementation of SMS regulations had an impact on the evolution of SMS, both within industry stakeholders and TC oversight practices. While there has been improvement, most notably during the past five years, the lack of detailed guidance to industry on how to properly implement an SMS within the enterprises, combined with the lack of timely and comprehensive training for TC inspectors, contributed to the confusion surrounding regulatory interpretations for several years post-implementation, something which persisted at the writing of this report. While enterprises are now more comfortable with SMS, there remains some disconnect in parts of the country between TC inspectors and industry that could be rectified to a large extent by improved training for TC inspectors, for industry, or joint training for industry and TC.

Long-term Risks related to SMS in Civil Aviation

Interviewees identified as key risks: TC’s perceived retreat from its oversight responsibilities, complacency or drift in organizations regarding SMS, shortage of qualified people, and lack of collaboration within the industry.

Recommendations

Our evaluation made the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1:

To realize the full benefits of SMS, TC should explore ways with the civil aviation enterprises to improve their root cause analysis capacity.

Recommendation 2:

TC should determine the extent to which organizations’ risk assignment practices are appropriate and take the necessary steps to mitigate if it detects a pervasive issue.

Recommendation 3:

In order to be able to conduct quantitative analysis of SMS’ impact on aviation safety Transport Canada should identify its information needs, and develop and execute a data strategy to address those needs.

Recommendation 4:

TC should build capacity for continuous improvement in industry by encouraging innovative approaches to safety management that go beyond regulations while still meeting minimum expectations and safety standards.

Recommendation 5:

TC should ensure that updated training addresses the issues raised in this report, that is, it is consistent across regions, occurs in a timely fashion, and is relevant to assessing SMS in practice. Inspectors need a shared understanding of SMS principles and applications, and this knowledge should be refreshed regularly.

Recommendation 6:

TC should engage with industry and TC inspectors to explore what level of collaboration in risk assessment and data-sharing is appropriate. TC could determine data needs for monitoring/improving aviation safety and assess the feasibility of more open data-sharing, which would be particularly relevant for smaller organizations, who may not generate sufficient data as individual entities and may therefore greatly benefit from aggregated data for trend analysis.

Evaluation of Safety Management Systems in Civil Aviation

Introduction

Since 2008 a number of commercial operators, aircraft maintenance organizations and aerodromes began implementing Safety Management Systems (SMS) as it became a requirement under Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs). Evaluation and Advisory Services conducted an evaluation of SMS in Civil Aviation in 2017-2018 in order to answer two key questions: after 10 years of implementation what has been the impact of SMS on aviation safety and what lessons were learned from SMS roll out and implementation? The primary intent is to contribute to policy discussions and decision making regarding the future direction of SMS in civil aviation.

The evaluation was included in the Department’s 2016-2017 Evaluation Plan and was conducted between July 2017 and November 2018.

Program Profile

Overview

The Transport Canada Civil Aviation Directorate (TCCA) is responsible for the regulation and oversight of civil aviation transportation in Canada. In the civil sector, TCCA oversees air operators, aircraft maintenance organizations, aerodrome operations, air navigation services, and aeronautical product designers and manufacturers.Footnote 1 As part of its regulatory role, TCCA is responsible for the development and distribution of policies, standards, regulations, and guidance and educational material.Footnote 2

TCCA’s oversight activities are divided into two categories: service and surveillance. Services include licensing for pilots, maintenance engineers, and air traffic controllers; medical assessments of personnel; the certification of aeronautical products; confirming aerodrome safety; and granting operating certificates to air operators, aircraft maintenance organizations, and other operations in the industry. Surveillance involves conducting inspections and assessments of organizations to confirm compliance with the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs).

Safety Management Systems at TCCA

A Safety Management System (SMS) is a documented process for managing risks that integrates operations and technical systems with the management of financial and human resources to ensure aviation safety or the safety of the public. It is a risk-based and “business-like” approach to safetyFootnote 3 - with clear accountabilities, policies, and structures where responsibilities and processes are explicitly defined and documented.Footnote 4 Individual organizations draft their SMS based on guidance from TCCA, which results in unique SMS tailored to each organization. The intent is for an SMS to become part of the culture of an organization and everyday work.

Internationally, SMS became a requirement of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) in 2006 as part of the State Safety Program requirements. As of 2013, with the adoption of Annex 19, SMS is an ICAO requirement for all aviation service providers.Footnote 5 This applies to operators who conduct international transport, flight training organizations, maintenance organizations, manufacturers, aerodrome operators, and air traffic services.Footnote 6 Although the SMS is a requirement, member states are permitted to inform ICAO if it is not possible within their individual context. Canada was the first member state to begin implementing SMS.Footnote 7

In deciding to implement SMS, the overall anticipated result was stronger safety culture and general improvement of safety practices.Footnote 8 In addition to the ability to identify and manage any safety issues or risks before an incident/accident occurs, TCCA indicated that there would also be various benefits such as financial savings due to reduced incidents and accidents, improved efficiency and productivity within an organization.Footnote 9 In changing the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) to include SMS, it was noted that no alternative existed and that SMS was likely to have a net positive benefit-cost impact.Footnote 10

Surveillance Methodologies at TCCA

TCCA’s surveillance methodologies have changed significantly over the last decade. Prior to SMS implementation, TCCA focused on regulatory compliance through the examination of personnel, aircraft, and activities using audits and inspections. Inspectors looked at specific products and practices to see if they met the relevant regulatory requirements and standards.

At the time of SMS implementation, TCCA was also undertaking an overarching transition from its audit-based oversight to a more risk-based and systems-focused approach. New surveillance tools were developed: Program Validation Inspections, Process Inspections, and, for organizations who would have SMS, Assessments.Footnote 11 To support the implementation of SMS, TCCA surveillance resources were focused primarily on these broad assessments, which consisted of a thorough consideration of an organization’s entire system.

However, under this risk-based surveillance approach, all companies could not be inspected as part of planned surveillance due to high-risk priorities as well as TC resource limitations. In response to this and to feedback from inspectors and the Auditor General, TCCA began the Surveillance Program Evaluation and Update (SPEU) project in 2016. This project led to an updated surveillance approach, Surveillance 2.0, in effect as of April 1st, 2018.

Current Surveillance Approach

Surveillance can occur on two fronts: planned or reactive. Planned surveillance consists of activities scheduled at the beginning of each fiscal year based on a variety of risk factors and safety information, while reactive (unplanned) surveillance includes “activities conducted in response to an unforeseen event or issue (accident, incident, increase in an enterprise risk indicator level, etc.).”Footnote 12

Traditional surveillance policy dictated that the examination of organizations occur at specific time intervals (and if not, the decision to delay surveillance was justified based on a risk assessment). With updates to surveillance practices, the goal became “a more robust risk-based decision making framework”Footnote 13 in order to ensure oversight activities are flexible and focused on risk rather than simply time. Surveillance 2.0 continues to strive for this.

Currently, there are multiple types of surveillance of regulated entities that TCCA can conduct: process-level surveillance, systems-level surveillance, as well as targeted inspections for companies not currently subject to SMS regulations.

As of 2018-2019, process-level surveillance is the primary means of oversight. Process-level surveillance looks at the functioning of a specific process within the SMS or other system to determine whether it is effective and compliant. TCCA manages this through a process inspection (PI). While originally used primarily as a reactive tool, PIs now allow for quick review and sampling to evaluate how an enterprise is operating. These inspections can lead to additional systems-level surveillance if needed.Footnote 14

Choosing the process to inspect involves preliminary analysis to determine which process is most relevant to the reason or trigger for inspection. PIs may be planned, reactive, part of a systems-level check, or used to support oversight services (e.g., ramp inspection to support the addition of a new aircraft type).Footnote 15

To assess a system, TCCA uses either assessments or Program Validation Inspections (PVI). The primary differences between assessments and PVIs are the points of entry and the timelines. Assessments are used for organizations that have a Safety Management System in place, thus making the scope or focus of the assessment the system itself. For PVIs, on the other hand, the scope is slightly smaller and focused on a unique system, program, or procedure (e.g., the Quality Assurance Program or training program).Footnote 16 Differences in timelines may occur throughout the surveillance process; for instance, in notifying an enterprise about upcoming on-site activities, 10 weeks’ notice is required for an assessment, as opposed to 6 weeks for the more concentrated Program Validation Inspection. In every other area, PVIs and assessments follow the same general process.

Current Status of SMS in Canada

In Canada, SMS is now in place for all airline operators, private operators, approved maintenance organizations who service airline operator aircraft, air navigation services, and aerodromes/airports/heliports. Further implementation was put on hold in 2009.Footnote 17 At the writing of this report, it has yet to be implemented with smaller operators (i.e., commuter, air taxi, and aerial work organizations), other approved maintenance organizations, flight training units, approved manufacturers, or aeronautical product certification.Footnote 18

Evaluation Approach and Scope

The evaluation covers the period from 2005-06 to 2016-17. The evaluation scope includes all aviation organizations subject to SMS regulations (except for the two air navigation service providers) with an emphasis on commercial operators.

This evaluation focuses on the impacts of SMS implementation in the civil aviation industry, rather than the effectiveness of TC’s oversight. While surveillance practices and related activities are considered, this is to provide a clear picture of SMS, as the role of the regulator cannot be fully disentangled.

Evaluation Methods

Our evaluation employed multiple lines of inquiry, including a document and literature review, stakeholder survey, interviews, and case studies.

Stakeholder Survey

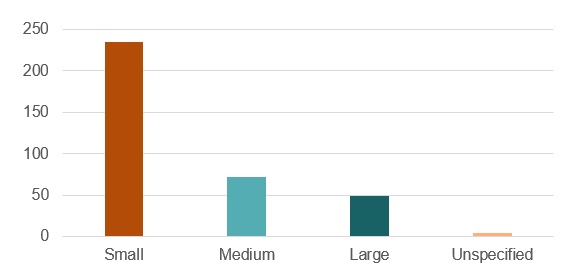

In November/December 2017, an anonymous online survey was deployed to a total of 1799 industry stakeholders, including 804 operators, 296 air maintenance organizations (AMOs), and 699 aerodromes. We received responses from a total of 360 industry representatives (213 operators, 62 AMOs, 85 aerodromes). Of these 360 respondents, 235 were classified as ‘small’ (1-10 employees) organizations, 72 were medium (11-50), 49 were large (51+), and 4 did not specify size. The organization size refers to number of employees within organization who have responsibilities defined under the Canadian Aviation Regulations (e.g. Pilot, Aircraft Maintenance Engineer, Cabin Safety Personnel, Person Responsible for Maintenance).

The overall response rate was 20%.

Figure 1: Survey respondant organizations by size

Figure 1: Text version

This figure is a bar graph showing the number of survey respondents by organization size. The far left bar shows that 235 respondents were classified as small organizations. The second-to-left bar shows that 74 were from medium organizations. The middle bar shows that 49 respondents were from large organizations. The far right bar shows that 4 did not specify size.

Below is the further breakdown of survey respondents. Contact information was derived from the TCCA Directorate database. Several cleaning and formatting steps were taken to arrive at the final contact list for the deployment of the survey, including the removal of organizations with no or incomplete contact emails, scanning through all emails and fixing formatting, aggregation of all emails into master list and removal of duplicates. In cases where there was identical contact email for several organizations, preference was given to operators with other entries removed from master list.

Table 1

| Aerodromes | Operators | AMOs | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall in the TCCA database |

1982 |

824 |

776 |

3582 |

| Master list for survey deployment |

699 |

804 |

296 |

1799 |

| Total responded |

85 |

213 |

62 |

360 |

| Partial and full SMS implementation |

68 |

133 |

19 |

220 |

| Voluntarily |

6 |

72 |

7 |

85 |

| Because of regulatory requirements |

46 |

20 |

7 |

73 |

| Both of the above |

16 |

41 |

5 |

62 |

Survey questions explored the implementation and the current status of organizations’ SMS, inquiring about topics such as benefits of SMS, types and utility of guidance, and useful or challenging elements of SMS.

Interviews

Interviews were conducted in-person and over the phone with industry stakeholders, TC staff, and Transportation Safety Board (TSB) officials. These key informants provided detailed insight into SMS in aviation based on their experiences and perspectives. Separate interview guides were prepared for industry, TC, and TSB participants.

An introductory round of interviews was conducted with industry participants including representatives from 24 air operators and 2 aerodromes, totaling 26 interviews. The majority (19) of these organizations were considered ‘large’ with 51+ employees, with the remainder (7) having under 50 employees. The interviews were conducted by Evaluation and Advisory Services (EAS) in November and December 2017.

Between May and August 2018, EAS conducted interviews with 15 TC staff including Inspectors, Technical Team Leads, and higher level officials.

Three representatives from TSB participated in a group interview in September 2018.

Case Studies

To provide a more nuanced understanding of SMS in practice in the Canadian aviation industry, case studies were conducted in 3 provinces (Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia) with a total of 8 companies. Case study companies were selected to ensure a regional spread of diverse operational contexts (e.g., coastal, commuter, oil and gas) and to include different sizes and types of operations (e.g., passenger versus cargo).

Site visits and interviews took place between May and July 2018. The case studies yielded 43 interviews with various company representatives, including: Presidents and Vice Presidents; Directors and Managers of SMS, Quality Assurance (QA), Maintenance, and Operations; Chief Pilots; and ground-level staff. In addition, 21 interviews were conducted with TC inspectors in the regions as part of the case studies.

Document and Literature Review

Key internal and external documents were reviewed to provide a full picture of safety management systems in theory and in practice, with special attention to SMS in Canada and SMS in aviation. The review considered Civil Aviation regulations and standards, internal and publically available guidance materials (e.g., Staff Instructions, Advisory Circulars, training presentations, and promotional documents), TC reports and presentations, findings by the Auditor General of Canada, and ICAO documents. This material was considered alongside literature by academics and experts exploring safety culture, the measurement of safety performance, and the development and impacts of SMS.

Considerations

We note the following considerations and limitations for this evaluation:

- 1) While an in-depth statistical consideration of quantitative safety data would be ideal, such an analysis was not possible at this time due in part to limitations in TCCA’s current data management tools and practices. TCCA provided information such as operator reports for case studies. However, through discussion with TCCA staff (representatives from both Aviation Safety Intelligence, and Policy and Regulatory Services), it became clear that more fine-grained data (e.g., accident rates per subpart based on aircraft movements or flight hours; specific safety issues identified by inspectors) could not be feasibly analyzed by the evaluation team, due to lack of availability and/or centralization of data.

- 2) We selected case study companies through consideration of traits such as organization type, size, and geographical context. As such, the selected organizations provided rich insights into SMS as applied and experienced in different contexts. However, participating companies were not selected through random sample, and may not be statistically representative of all SMS companies in Canada.

- 3) Finally, while our report offers insight into areas that are building blocks of safety culture in participating organizations, it is not a comprehensive assessment of the safety culture in those organizations. Assessing the safety culture of a group of organizations in a rigorous manner requires methodologies that were not feasible for this evaluation. For example, it is recommended at a minimum to deploy a survey that is ideally completed by all of the employees of an organization. ICAO also recommends this approach. As noted earlier, while we did deploy a large survey that was sent out to over 1700 civil aviation organizations, it was completed by organizational representatives only. For this reason, the survey focused on implementation rather than safety culture.

Evaluation Findings

Section 1: Safety Outcomes of SMS

Summary Statement

We found that a number of organizations have in place traits and practices that are indicative of an effective SMS; there are numerous examples of hazards being identified and measures being implemented to address those hazards. There is also notable buy-in to SMS, especially amongst larger operators, and many would have an SMS even if it was not a regulatory requirement. Taken together, these point to a positive impact on aviation safety.

Introduction

In this section we report on:

- - Stakeholder views on perceived SMS safety benefits, with a focus on our stakeholder survey;

- - The extent to which enterprises had in place key attributes and practices that are known to lead to an effective SMS; and,

- - Challenges related to quantitative analysis to attribute SMS impact on safety performance.

A key question we asked for this evaluation was: after 10 years of implementation, what has been the impact of SMS regulatory requirements on civil aviation safety? To answer this question, we focused on the basic common attributes of an SMS to ascertain – through case studies, interviews with civil aviation organization representatives and TC staff, a survey of civil aviation organizations, and a document review – how well some organizations have done with respect to those attributes, particularly the level of commitment and proficiency applied.

The rationale for focusing on key SMS attributes to gauge safety impact is two-fold. First, there are inherent challenges associated with trying to assess direct impact SMS on aviation safety using aggregate statistics of occurrence rates or over a period of time – something we discovered during our evaluation as well. There is wide support in literature that analysis based on aggregate statistics does not always provide optimal insight into SMS effectiveness – “Many modern approaches advocate the use of proactive measures such as safety climate, hazard identification, and the observed percentage of safe behaviour with the focus being on current safety activities to ascertain system success rather than on system failure.”Footnote 19 Second, SMS is as good as what everyone involved puts into it – “all the elements of a SMS can be in place, but if people are not using or following them, the efforts are futile.”Footnote 20 A comprehensive study which carefully examined research across the world on this matter concluded that the effectiveness of SMS may well not lie in the “specific components of the system, but rather in the level of sophistication and effort applied across the system.”Footnote 21

Organizations’ Views on SMS Safety Benefits

Finding 1:

Larger organizations believe that SMS enables them to address safety risks. That belief is less present amongst smaller organizations.

In our survey, we asked organizations to rate, on a scale of 1 to 5, the importance of SMS in enabling their organization to address emerging safety risks, with 5 being ‘rely extensively on SMS’. The larger the organization, the more they relied on SMS to address emerging safety risks. The majority of medium (81%) and large (84%) organizations chose at least 3 out of 5; two thirds (66%) of larger organizations responded 4 or 5. On the other hand, just over a half (53%) of small organizations picked at least 3 out of 5.

Figure 2: The larger the organization, the greater importance it places on using SMS to address emerging safety risks

Figure 2: Text version

This figure is a horizontal stacked bar graph. Each line represents the importance of SMS to organizations based on their size. The bars show six levels that respondents could choose, ranging from 0 (do not use SMS) to 5 (rely extensively on SMS). The top bar displays responses from small organizations: 2% indicated a level of 0, 20% selected a level of 1, 24% selected a level of 2, 20% selected a level of 3, 23% selected a level of 4, and finally 10% selected a level of 5.

The middle bar displays responses from medium organizations: 4% indicated a level of 0, 9% indicated a level of 1, 7% indicated a level of 2, 32% indicated a level of 3, 30% indicated a level of 4, and 19% indicated a level of 5.

The bottom bar displays responses from large organizations: 11% indicated a level of 1, 4% indicated a level of 2, 18% indicated a level of 3, 33% indicated a level of 4, and 33% indicated a level of 5.

Another indicator of belief in safety benefits of SMS is seen when we look at organizations who have implemented SMS voluntarily. These organizations cite safety benefits as the top reason for implementing SMS, followed closely by positive impact on safety culture and continuous improvement, both key notions that underpin SMS.

Figure 3: Top five main reasons organizations voluntarily implemented SMS

Figure 3: Text version

This figure is a horizontal lollipop chart demonstrating the top five reasons organizations voluntarily implemented SMS. “Safety benefits” is listed at the top as being chosen over 100 times. This is followed by “positive impact on safety culture” (chosen between 75 and 100 times), “establish continuous improvement practices” (chosen between 75 and 100 times), “more effective and efficient operations” (chosen between 50 and 75 times), and finally at the bottom, “align with industry trend” (chosen between 50 and 75 times).

Most of the organizations we spoke with reported overall confidence in SMS, many highlighting its value-added as a systematic and documented way of identifying and addressing aviation risks. Overall, of the people we spoke to during the second phase of this evaluation, 59% (70% excluding those we did not ask) stated that SMS makes things safer for individual companies and 43% (60% excluding those we did not ask) stated that SMS makes things safer for the industry as a whole. An important observation for the evaluation is that several case study organizations as well as other industry participants we interviewed said that they would keep SMS even if it was no longer a requirement.

Civil Aviation Organizations and Key SMS Attributes

What follows are our observations on the extent to which enterprises had in place key SMS attributes that are known to be crucial for SMS effectiveness. We focused on the following attributes:

- Trust

- Non-punitive reporting

- Executive commitment

- Proficiency in investigations and analysis

- Continuous improvement

Trust

There is clear consensus in the literature and amongst interviewees that without buy-in and confidence in the system SMS will not be effective. The vital ingredient that drives confidence in the system is trust.

We examined two critical areas that both impact and are also shaped by the existence of trust in organizations in the context of SMS.

- Non-punitive reporting

- Executive commitment

Non-punitive reporting

Finding 2:

Amongst all the SMS elements we examined, non-punitive reporting is where we observed the clearest success.

Non-punitive reporting is a key feature of SMS. In order for an SMS to be effective, the culture in an organization must be informed, learning and reporting. If the culture does not encourage reporting, then a key foundation of this systematic approach to managing safety will be weak, as these reports feed into the data analytics, hazard identification and continuous improvement aspects of SMS.

Our survey results show that out of 17 SMS elements that are required by regulations, large organizations identified non-punitive reporting as the most important element of an effective SMS:

- Non-Punitive Reporting Policy

- Investigation and Analysis

- Proactive Processes

- Risk Management

- Communications

For smaller organizations non-punitive reporting was less important (for these, the most important element was Training, Awareness and Competence, followed by Communications).

Almost all of the organizations we interviewed agreed that non-punitive reporting is the cornerstone of an effective SMS. This is true both internally to the companies, and in terms of interactions between TC and companies.

Case study companies by and large appear to have embraced non-punitive reporting practices. Amongst all the SMS elements we examined, non-punitive reporting is where we observed the clearest success. For the most part, case study companies felt that the culture in their companies was open and amenable to reporting. Most spoke at length about their reporting scheme and stated that employees felt comfortable reporting and were well aware of the system. Organizations tracked reporting and many improved the process over time, primarily to maintain employee engagement in reporting. For example, some organizations made it easy for employees to report in from anywhere by automating the process or setting up an application on pilots’ phones. One company encouraged pilots “to share how their day went [immediately] instead of waiting to fill something out on the computer three days later”. This led to better data. Some companies used practices such as sending a letter in response to each report to demonstrate that management is taking reports seriously. In general, organizations noted that since SMS implementation, employees use reporting to tell management if they have an issue with something, whether it is safety-related or otherwise. It has improved internal communications and, according to several organizations, has taken the fear out of communicating a problem to senior staff. Employees no longer feel an impulse to cover up an issue or a mistake because they know that reporting it will lead to a fix and not punitive actions.

The non-punitive aspect is significant and supported by literature. Studies surrounding blame indicate that where punishment is feared people are less open to sharing information or admitting mistakes. If a culture is instead built around openness and does not lead to punishment, individuals are more likely to report. The focus is then forward-thinking, looking for opportunities to learn and improve, rather than blame.Footnote 22 TC made clear to organizations at the outset that reporting was to be non-punitive.

We also noted a number of challenges. The success of non-punitive reporting policy led to a substantial increase in the number of reports in some organizations. 47% of our case study company interview participants (80% if we exclude those who did not mention it either way, positively or negatively) noted managing reports as a challenge.

Ensuring that the non-punitive policy is not abused and maintaining confidentiality (particularly in small organizations, where keeping reports anonymous may be difficult) were also noted as challenges. Some reported that getting new employees such as pilots hired from a smaller operation to trust that the system is, in fact, non-punitive can take time.

Executive Commitment

Finding 3:

The level of executive commitment and support appeared to be fairly strong in many of the companies that were part of our case studies. However, there is anecdotal evidence that this support is occasionally tested by resource considerations.

Executive commitment is a key element of establishing and maintaining an effective SMS (an accountable executive is required by SMS regulations). There is extensive literature that emphasizes the importance of leadership commitment to developing and maintaining an effective safety culture.

Most interviewees highlighted the importance of senior management commitment. Interviewees accept as true that management behaviour influences the culture of the organization, and most critically, determines the level of resources dedicated to an SMS: “[SMS] will never work if there is no senior management support”; “Top executive’s commitment is critical success factor”; “The culture within a company is much more a result of the management than the fact of an SMS”; “At the executive level, if they haven’t bought into SMS, communicated it, and aren’t supporting it financially (training) then it will be very difficult for it to function.” As an example, if the senior executive sends the wrong signals regarding non-punitive reporting, the system will likely not be effective.

Several case study organizations demonstrated fairly strong executive support for SMS: “Each time we propose changes, we always get the support/buy-in from management”; “When the accountable executive sends the message that he welcomes any report and only positive recourse will happen then safety becomes a responsibility at all levels. There are open conversations on hazards as they arrive. It leads to commercial success.”; “Has been challenging keeping up with the reports so we had to hire more investigators and the AE supported this.”

One executive noted that resources dedicated to SMS relative to other areas in an organization is a sound indicator of executive commitment to SMS. For practical reasons, we did not attempt to obtain this information from the organizations. However, as we report in the Continuous Improvement section, executive support gets tested most acutely when it comes to improvements that go above and beyond regulatory requirements.

Proficiency of Investigations and Analysis

Finding 4:

Sound practices of investigations and analysis are occurring. However lack of technical capacity and resource pressures occasionally hamper their effectiveness; one of the consequences is that organizations may not always be assigning appropriate level of risk to risk occurrences in order to avoid undertaking investigations.

Learning from events and the identification and reduction of hazards are crucial features of an SMS. Identification of safety hazards and corrective action to mitigate those hazards is a common and critical element of an SMS not only in civil aviation or transportation but in all sectors where SMS is used. In Canada, SMS regulationsFootnote 23 require that enterprises have in place processes for: identifying hazards to aviation safety and for evaluating and managing the associated risks; internal reporting and analyzing of hazards, incidents and accidents and taking corrective actions to prevent their recurrence; and ensuring that personnel are trained and competent to perform their duties.

In our survey of aviation sector, out of 17 SMS elements, large organizations identified investigations and analysis as the second most important element of an effective SMS.

- Non-Punitive Reporting Policy

- Investigation and Analysis

- Proactive Processes

- Risk Management

- Communications

A review of literature highlights the importance of analysis and investigations for an effective SMS: “A healthy safety culture … vigilantly remains aware of hazards and utilizes systems and tools for continuous monitoring, analysis and investigation.”Footnote 24 In fact, SMS can be understood as a “planned, documented and verifiable method of managing hazards and associated risks.”Footnote 25 Realistically, “if you are to prevent the reoccurrence of an event, you need to understand what caused the event, and put in place strategies such that those causes are prevented from occurring again.”Footnote 26

In some case study organizations, sound practices of root cause analyses, investigations into hazards, and trend identification are occurring. Many of the organizations we spoke to felt that the way they conducted analysis, investigations, and trend identification has improved. Of our case study company participants, 60% (96% if we exclude those we did not ask) said trending was a key SMS benefit. The ability of SMS to identify trends that would not have been detected otherwise is viewed by many as the clear value-added of SMS. Put differently, a significant benefit of SMS is not simply catching a single event that is then corrected, but identifying a repetitive event that was thought to have been corrected. Many of the companies pointed to having no repeated events as an indicator of success.

Several examples were provided. One company had received an engine with the wrong data, showing half the hours that the initial data stated. An investigation led to corrective action, consisting of a change in process, where two people now received engines and validated each other’s work. To refine further, the company conducted an audit of all engines and every repair going back 30 years. In this case, SMS helping understand root causes resulted in a significant decline in the number of overruns. One company identified a trend involving extra weight on planes because of unloaded cargo. Another company created a working group to keep better track ground-handling procedures because a trend was noticed after a number of incidents. Yet another company found out they had never installed fire bags they had bought after an investigation into potential battery ignition – “this is how SMS works. It’s not just bird strikes and repairs; it’s also these other little things that you would never find until they cause you grief.”

The organizations that had in place sound practices regarding investigations and analysis emphasize timeliness and competence as key to effectiveness. Tracking trends and taking action to promptly and effectively address issues that have been identified is crucial. These organizations were keen to discuss and showcase their ability to “keep on top of things”.

Despite sound practices observed, in some organizations, resource- and time-related pressures or lack of technical expertise may be hampering the effectiveness of investigations and analysis. Some organizations reported that it can be hard to find the time for large scale investigations for severe and complicated incidents. Paradoxically, that may be due to success in the area of reports being generated by the system: “the worst enemy of the system might be its own internal success”. Others reported that lack of expertise can also be an issue. We’ve heard that organizations may not have people with investigations backgrounds and may therefore struggle with conducting root cause analysis. Several organizations reported that SMS requires skilled workers who understand SMS, the airline business, and how the two can work, and those types of workers can be hard to find.

Some TC inspectors expressed concern about some operators not assigning the appropriate level of risk to risk occurrences in order to avoid undertaking resource intensive investigations and analyses. They noted that occasionally companies tended to write SMS reports that suited them and “soft pedaled risk occurrences because it means they don’t have to do anything about it”. These inspectors point to an inclination on the part of some companies to assign risk based on the outcome rather than the potential hazard. We were provided several examples of incidents not being labeled as severe when they clearly appeared to be, and instead categorized as low-risk because they did not result in something serious. We note failure to assign the appropriate level of risk to occurrences as a key SMS risk and encourage a closer look by TC.

Recommendation 1:

To realize the full benefits of SMS, TC should explore ways with the civil aviation enterprises to improve their root cause analysis capacity.

Recommendation 2:

TC should determine the extent to which organizations’ risk assignment practices are appropriate and take the necessary steps to mitigate if it detects a pervasive issue.

Another challenge that larger organizations in particular may be facing is optimizing the use of the significant amount of data generated by SMS. For example, in one large case study company, there is a feeling of having “hit the wall in terms of doing effective stuff - correlating events, audit observations with all the data churned [by SMS]”. Their aim now is to identify and understand leading indicators in order to detect issues that have the potential to turn into a hazard in the future. Solutions such as a redesigned framework in tandem with software improvements are being considered, which would allow for equating indicators from SMS and linking these to risk profiles.

As noted in the Non-punitive Reporting section, 47% of our case study company interview participants (80% if we exclude those who did not mention it either way, positively or negatively) noted managing reports as a challenge.

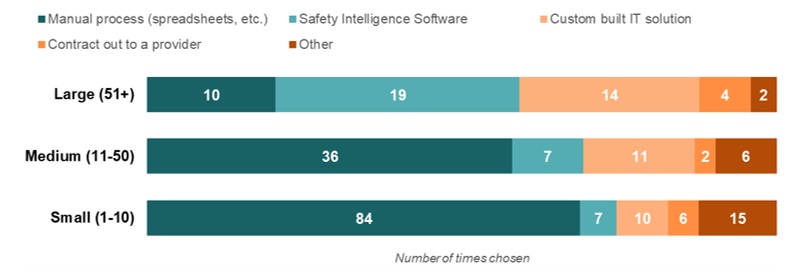

In our survey, we found that a majority of organizations rely on manual processes (e.g. spreadsheets, etc.) to process and manage their data (see Figure 4). As would be expected, the use of more advanced tools such as safety intelligence software is more prevalent amongst larger companies (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: The majority of organizations rely on manual process to manage and analyze safety data

Figure 4: Text version

A horizontal bar graph represents the processes companies use to manage and analyze safety data. The top bar indicates that 59% of survey respondents use manual processes (e.g., spreadsheets), followed by 16% using custom built IT solutions, 15% using safety intelligence software, 10% using other processes, and 5% who contract out to a provider.

Figure 5: For small and medium organizations, manual processes are most common, while more complex solutions are used by large organizations

Figure 5: Text version

This figure is a horizontal stacked bar graph indicating which processes were chosen by large, medium, and small organizations. The top bar indicates that large organizations (51+ employees) chose manual processes 10 times, safety intelligence software 19 times, custom built IT solutions 14 times, contracting out to a provider 4 times, and other 2 times.

The middle bar indicates that medium organizations (11-50 employees) chose manual processes 36 times, safety intelligence software 7 times, custom built IT solutions 11 times, contracting out to a provider 2 times, and other 6 times.

The bottom bar indicates that small organizations (1-10 employees) chose manual processes 84 times, safety intelligence software 7 times, custom built IT solutions 10 times, contracting out to a provider 6 times, and other 15 times.

Continuous Improvement

Finding 5:

While there is belief in the notion of continuous improvement and there are examples of it occurring, resource considerations and liability concerns at times mitigate against safety improvements that are beyond regulatory requirements.

Continuous improvement is central to SMS and to the notion of safety culture: “A healthy safety culture actively seeks improvements.”Footnote 27 In our survey of civil aviation organizations, continuous improvement is identified as one of the top reasons for implementing SMS (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Organizations cited safety conditions and continuous improvement practices as the top reasons for implementing SMS voluntarily

Figure 6: Text version

This figure is a horizontal lollipop chart listing the top reasons for implementing SMS voluntarily. The top bar shows that “safety benefits” was selected as a reason over 100 times, followed by “positive impact on safety culture” (chosen between 75 and 100 times), “establish continuous improvement practices” (chosen between 75 and 100 times), “more effective and efficient operations” (chosen between 50 and 75 times), “align with industry trend” (chosen between 50 and 75 times), “contractual obligations” (chosen between 25 and 50 times), “allocate resources based on better knowledge of risks” (chosen between 25 and 50 times), “competitive advantage” (chosen between 25 and 50 times), “Transport Canada promotion” (chosen just over 25 times), “interactions with partners or third party” (chosen just under 25 times), “increase access to market” (chosen just under 25 times), “insurance reasons” (chosen under 25 times), “ease of transition from existing Quality Management systems” (chosen under 25 times), “international requirements” (chosen under 25 times), “association encouragement” (chosen under 25 times), and finally “other” (chosen between 0 and 25 times).

Some case study organizations also cited continuous improvement as a key benefit of SMS. That said, we’ve heard that a challenge for both the regulator and the regulated organizations is making the shift from the mentality of focusing on regulatory compliance to relying on SMS. This challenge comes into sharpest focus with the notion of continuous improvement of safety, as resource and liability concerns at times may mitigate against safety improvements that are beyond regulatory requirements.

While some interviewees pointed out that they generally received support from the accountable executive for proposed changes and action was taken even if it was beyond regulatory requirements, we’ve also heard from others of instances where executives questioned the need for expending resources on improvements such as installing a piece of equipment that was not a regulatory requirement but would have had clear safety benefit, based on an investigation of a previous incident.

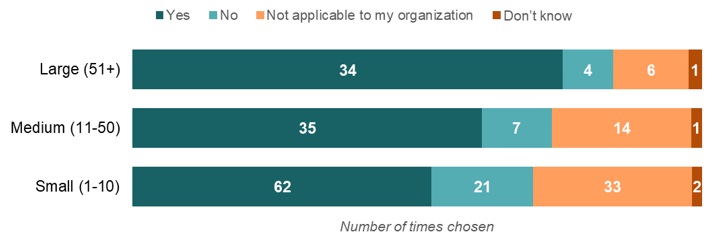

One relevant issue here is whether Quality Assurance (QA) extends to flight operations. While there is no regulatory requirement to do so, it is viewed as a sound practice. Our survey results show that for the majority of organizations surveyed, QA processes do extend to flight operations (see Figure 7). That said, we are also aware of organizations that discontinued this practice.

Figure 7: Overall, for the majority of organizations SMS quality assurance processes extend to flight operations

Figure 7: Text version

This figure is a horizontal stacked bar graph showing the use of SMS quality assurance in flight operations by organization size. The top bar indicates that of the large organizations (51+ employees) 34 chose “yes”, 4 chose “no”, 6 chose “not applicable to my organization”, and 1 chose “Don’t know”. The middle bar indicates that of the medium organizations (11-50 employees), 35 chose “yes”, 7 chose “no”, 14 chose “not applicable to my organization”, and 1 chose “don’t know”. The bottom bar indicates that of the small organizations (1-10 employees), 62 chose “yes”, 21 chose “no”, 33 chose “Not applicable to my organization”, and 2 chose “Don’t know”.

Liability concerns can also stifle continuous improvement. This is true for both the regulated organizations and the regulator. We’ve heard that organizations are wary of doing things like including best practices in their manuals that are beyond regulations, for fear that they may be held accountable if something goes wrong. Similarly, TC inspectors may not want to approve processes or approaches that are beyond regulations because they are also concerned about being held accountable if there is an occurrence (for example, by TSB).

The challenges associated with continuous improvement appear to be a natural consequence of operating for a long time in an environment characterized by a focus on compliance with regulations. If the apprehension we have heard about taking on the potential liability is representative of the aviation sector, this poses an interesting challenge, as continuous improvement is a central feature of SMS and one of its major selling points.

Recommendation 3:

TC should help build capacity for continuous improvement in industry by encouraging innovative approaches to safety management that go beyond regulations while still meeting minimum expectations and safety standards.

Empirical Data

Finding 6:

We observed that enterprises have in place effective SMS practices that are known to improve aviation safety. There is also significant international research that shows a correlation between SMS and improved safety performance. However a lack of objective safety data constrained the evaluation’s ability to attribute statistically SMS’ contribution to aviation safety in Canada.

There has been a downward trend in aviation accidents over the last decade in Canada. The Transportation Safety Board’s (TSB) 2017 statistical summaryFootnote 28 shows that the accident rate in Canada’s aviation sector has decreased since 2007 (see Figure 8). This rate is based on all accidents (commercial or otherwise) reported to TSB and the total number of flying hours recorded by TC.

Figure 8

Figure 8: Text version

This figure displays a bar graph with an overlain line plot and a trend line. The bar graph shows the number of aviation accidents per year from 2007 to 2017. In 2007, there were under 300 aviation accidents. In 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013, there were between 200 and 250 accidents. In 2014, there were just over 200 accidents. This increased in 2015 to between 200 and 250 accidents. In 2016, there were just under 200 accidents. In 2017, this increased slightly though still remained below 200.

The two overlain lines represent the accidents per 100,000 flying hours between 2007 and 2017 and the trend in this accident rate over time. These lines show a decline in the accident rate, from approximately 6 accidents per 100,000 flying hours in 2007 to approximately 4 accidents per 100,000 flying hours in 2017.

However, demonstrating the extent to which SMS contributed to this downward trend on the basis of objective safety data has proven challenging for our evaluation. A key hurdle is that the aircraft accident rate calculated as the number of accidents per hours flown or per number of movements (takeoff or landing) cannot be calculated by CARs subparts (e.g., 705 certificate holders) because TC no longer collects the hours flown or number of movements by CARs subparts (see Considerations section on page 13 for an explanation of the limitations the evaluation encountered in conducting statistical analysis).

To be fair, even if more fine-grained data was available, there are inherent limitations to this type of analysis. Attributing causes to safety improvements is complex as there are a variety of factors to consider, including the implementation of SMS and improved technology (e.g. better aircraft). At least eight interviewees echoed these views, many singling out improved technology as a key contributor: “Part of the problem when you look at the data saying aviation is safer now … look at the fleet. Airbus is safer. Those old aircrafts are being thrown out. There’s been a fleet renewal within civil aviation in Canada which has lowered the rates of incidents”; “[SMS] played a part in [improving] safety but advancing technology has had the biggest impact on safety”. Several interviewees pointed out that complying with IATA Operational Safety Audit (IOSA) also contributed to safety, for some, more so than SMS.

That said, there is ample research evidence that show a correlation between SMS and safety performance, including research that has studied various models and indicators of safety, factoring in safety climate, proactive hazard identification, and safety behaviours in addition to considering accident rates over time. For example, YeunFootnote 29 analyzed the Flight Safety Foundation’s Basis Aviation Risk Standard audit data from 2011 to 2014 and found that as the number of audits increase, the number of observations generally do also, but in the years following SMS implementation the number of audit observations decreased. Similarly, a survey of companies with and without SMS in different industries found higher safety performance and better risk assessment amongst companies with SMS.Footnote 30 All of this suggests that SMS does improve safety performance and there is no reason to believe that Canada’s experience with respect to SMS in civil aviation has been any different.

Recommendation 4:

In order to be able to better conduct quantitative analysis of SMS’ impact on aviation safety Transport Canada should identify its information needs, and develop and execute a data strategy to address those needs.

Conclusion

We found that that in some organizations a more systematic and documented way of identifying and addressing aviation risks is taking hold, a measure of hazard identification and mitigation is occurring, and there is notable buy-in to SMS amongst large organizations in particular. Specifically:

- There is strong agreement amongst stakeholders, as well as independent research that when implemented well SMS will reduce risk in an organization’s operations. We have observed a number of organizations that appear to have in place traits and practices that are known to be conducive to an effective SMS and some basic SMS elements appear to be well implemented. That said, these sound practices and traits are not evenly distributed across organizations or key SMS attributes.

- Through interviews and visits to organizations that were part of our case studies, we compiled a number of examples of hazards being identified and measures being implemented to address those hazards.

- Finally, there is survey evidence showing that, amongst large organizations in particular, there is a belief that SMS enables them to address safety risks. The fact that a number of organizations we spoke to indicated they would have an SMS even if it was not a regulatory requirement is also indicative of belief in SMS effectiveness.

All of this is indicative of positive impact of SMS on aviation safety in Canada. However, due in part to data limitations and in part to inherent difficulties of attributing SMS impact statistically, we were not able to quantify the extent of SMS’s contribution to aviation safety.

Section 2: SMS for Smaller Operators

Introduction

One of our lines of inquiry is to ascertain the extent to which SMS is scalable, that is, could be adopted by a civil aviation organization regardless of the size of the organization. Specifically we wanted to know the aviation sector views whether and how effectively SMS could be implemented by smaller operators. The intent is to inform policy discussion and decision making at TC around potentially expanding SMS regulations to other operators.

The issue of scalability is forward-looking. The analysis in this section is therefore prospective, which is different from most evaluation methods, which are typically used to answer questions about what has happened in the past. However, evaluation tools can be used to provide useful information about priority policy issues.

Summary Statement

With respect to scalability of SMS, the majority of interview respondents believed SMS can be useful to any size organization, while some believed SMS would not add value to some of the smaller operations. There is agreement amongst interviewees that if SMS is extended to additional certificate holders, it will be important for TC to adapt the current SMS requirements to fit the need and capacity of small organizations. Our survey and interviews show that documentation burden; cost/resource considerations; training, awareness and competence; and lack of perceived benefits of SMS are factors that are much more significant for smaller organizations than larger ones.

Finding 7:

The majority of interviewees indicated that SMS would be useful for all sizes of organizations and scalable, while others were skeptical that SMS would be useful for very small organizations.

According to TSB, the basic principles of SMS are scalable:

- Commitment from senior management to operate safely

- A process based on the ability to identify and document operational risk and undertake actions to mitigate risk

- A feedback scheme such as a reporting system

Many interview participants feel that SMS is valuable and possible for an organization of any size: “Aviation companies shouldn’t be running without a valid SMS program”; “702s and 703s should absolutely have SMS.”; “It’s a culture, you don’t need a large staff.” Some interviewees, however, are skeptical of whether SMS makes sense for some of the smaller organizations. What follows is a sample of responses that illustrate this view. “There definitely isn’t a perfect solution. A lot of bush / northern operators have one or two airplanes, the owner is the chief pilot and PRM and he might have two pilots who seasonally work for him and he’s probably 70 and his wife does all the paperwork. When you do an inspection, you go to his house. A good 25% are like this. In this context, SMS doesn’t make sense – waste of time and effort.”; “I really don’t think SMS belongs in an airport with one employee. It’s unrealistic to think that this could work and that they need it.”; “[I] don’t think it would be an effective tool for them. The idea behind SMS is a good one. But … [to] have small companies document what they’re doing would be a huge burden on finances and documentation.”; “SMS tries to manage safety issues in large organizations but for a small organization, it is a complete waste of time and money. Safety in small organizations should be a discussion – issues can be managed by just talking to each other, don’t need all the documentation.”

A few interviewees provided a “size threshold” below which they believe SMS would not be beneficial: “5-7 people? Doesn’t need SMS. In a small operation, need TC to come in and see you’re following safety protocol. In this context, safety can be easily and quickly assessed.”; “For a 2- or 10-person organization, it doesn’t make sense. Upwards of 50, SMS is fitting.” However, most interviewees did not provide a specific threshold when directly asked.

Overall, the majority interview respondents believed SMS can be useful to any size organization, and some believed SMS would not add value to some of the smaller operations. However, there is notable agreement amongst those we spoke to that if SMS requirement is extended to smaller organizations, TC will need to adapt the current SMS scheme to fit the need and capacity of these small organizations.

When prompted on how to adapt the current SMS scheme to fit the need and capacity of these small organizations make SMS, there weren’t many specific ideas put forth. When directly asked whether it’s a question of having fewer elements than the 17 found in the current SMS regulatory requirements, almost no respondent agreed (one interviewee likened the idea to having a car with three wheels). When asked whether it’s a question of making the expectations that define these elements less exacting, there were more who agreed. However, most of the comments centered on capacity of smaller organizations.

What follows are considerations when thinking about expanding SMS to additional certificate holders – in particular the small operators.

Finding 8:

Financial concerns, documentation burden, training/competence and perceived lack of benefits are key hurdles when considering how SMS can be successful in small companies.

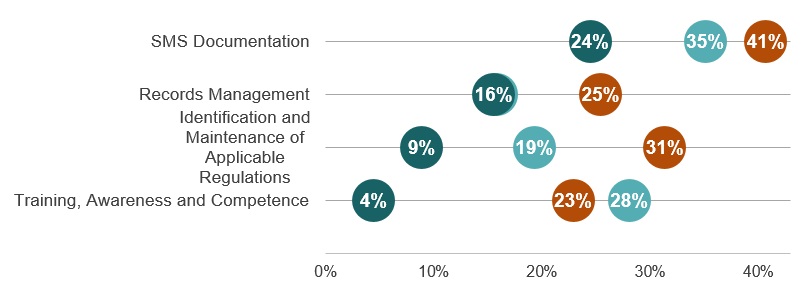

In addition to significant cost and resource concerns for medium and small organizations discussed in the previous section, documentation burden, as well training, awareness and competence are also key hurdles. In our survey, amongst all SMS elements, small organizations flagged these two SMS elements as most challenging to implement. As seen in Figure 9, smaller organizations identified documentation, records management, and identification and maintenance of applicable regulations the most challenging to implement. Several interviewees also flagged documentation burden as an important obstacle when thinking about SMS in small organizations. On the basis of our survey and interviews, it is clear that documentation requirements will need to be trimmed for small operators.

Training, awareness, and competence is one SMS element where we find the sharpest contrast between large organizations and small/medium organizations. In our survey, it was identified as challenging to implement both by small and medium size organizations (23% and 28%, respectively), much more so than large organizations (4%). This places onus on TC to provide appropriate support to smaller organizations, in particular guidance. A lesson learned for the initial implementation noted in this evaluation was that TC’s guidance materials were viewed as lacking.

Figure 9: For several SMS elements, a significantly higher proportion of small organizations identified them as challenging to implement, compared to medium and large organizations

Figure 9: Text version

This graph demonstrates the most challenging elements of adopting SMS by organization size. SMS Documentation was indicated as a challenge by 24% of large organizations, 35% of medium organizations, and 41% of small organizations. Records Management was indicated as a challenge by 16% of large organizations, 16% of medium organizations, and 25% of small organizations. Identification and Maintenance of Applicable Regulations was indicated as a challenge by 9% of large organizations, 19% of medium organizations, and 31% of small organizations. Training, Awareness, and Competence was indicated as a challenge by 4% of large organizations, 23% of medium organizations, and 28% of small organizations.

Lack of perceived SMS benefits is another key challenge when thinking about SMS adoption by smaller companies. In our survey, this viewpoint is cited as a key reason for not adopting an SMS, more so than financial reasons.

Some interviewees indicated that elements such as communication may be easier for smaller organizations, as all employees would likely be located in the same building. Other interviewees were concerned that, considering cost is the big driver civil aviation, not requiring all carriers (e.g., 704 certificate holders) to have an SMS creates an uneven playing field.

When considering how SMS may work with small organizations, the experience of small aerodromes provides useful insight. We’ve heard that several small aerodromes dislike the additional regulatory burden and don’t necessarily view it as vital for safety. Some TC inspectors we interviewed say they noted a lack of buy-in from some airports, as they don’t see the value of SMS. Very small airports don’t have the capacity to handle the administrative burden resulting from SMS. These have only a few staff, with little or no experience with SMS in many cases. In addition to other duties, responsibilities associated with SMS can be overwhelming: “one person managing an airport who does basically everything, you already have a guy who is putting in 60 hours a week, and now he’s supposed to have weekly safety meetings and things on top of this. SMS is geared for a bigger organization and the requirements are out of place for these smaller organizations”; “Manager of garbage within a town is also the airport manager, and you’re asking that person to also upkeep an SMS?” In addition to extra workload, maintaining an SMS requires skills that some airport managers might not have, such as computer skills and ability to understand all the different processes, and the towns don’t have the budget to hire a more suitable person.

The experience of smaller aerodromes show that in their current form SMS regulatory requirements are viewed as overly burdensome to implement and maintain, with no clear safety benefits, reflecting the results of our survey. If the SMS requirement is extended to additional certificate holders, it would be reasonable to assume that the experience of smallest operators (of which there are many) would not be significantly different than that of small aerodromes.

Conclusion

In considering the scalability of SMS, TC will need to heed the lessons learned from the initial roll-out. For example, TC will need to ensure that more effective, clear and consistent guidance is provided, both through its guidance materials and the interactions of inspectors with organizations. TC will also need to be effective in articulating clearly to smaller organizations the benefits as well as resource implications of adopting whatever form of SMS it proposes to facilitate buy-in. In other words, TC needs to communicate well why having an SMS is better, why the cost is justified, and that it will deliver on providing effective support and guidance.

Another key lesson learned from the initial SMS roll-out is that there needs to be robust analysis and realism about the resource implications on the Department of extending SMS to smaller organizations. Numerous interviewees noted that TC underestimated resource implications of initial SMS roll-out and subsequent oversight. The Auditor General found in 2008Footnote 31 that TC did not appropriately document risks and identify personnel needs. It found in 2012Footnote 32 that TC’s human resources planning had improved, though substantial work remained to determine the actual resources needed for surveillance. Regardless of the type of SMS configuration (e.g., SMS-light), extending SMS requirements to additional small organizations – which make up the bulk of the industry with over 2900 entities – has the potential to place significant pressures on TC. Resources will need to be expanded by TC for the roll-out – inspectors need to be fully trained and available to guide small organizations (of which there are a considerable number) in their implementation, data collection and analysis to ascertain the impact of SMS, and useful guidance materials prepared. In addition, TC will in all likelihood need to promote and facilitate information-sharing between small organizations more extensively.

Finally, TC will need to ensure sufficient resources are available to maintain an adequate (however that is defined) level of ongoing oversight. As one key informant stated “smaller operators may not have the resources to develop an SMS and might go in a problematic direction without proper oversight.” This is in line with literature that in terms of regulatory approach small organizations tend to require more deterrence rather than large ones. However, “unless it is carefully targeted, [this approach] can actually prove counterproductive, particularly when it prompts firms and individuals to develop a culture of regulatory resistance.’”Footnote 33

Section 3: SMS in Practice

Introduction

In this section we discuss issues related to the practice of SMS both within TC and amongst industry stakeholders. The manner in which regulations are initially rolled out can have an impact on their successful implementation. Therefore, the evaluation conducted document review, the stakeholder survey, and key informant interviews with both TC staff and case study companies to determine ongoing effects from TC’s initial SMS implementation.

Summary Statement

The evaluation examined the way implementation of SMS regulations had an impact on the evolution of SMS, both within industry stakeholders and TC oversight practices. Three key themes emerged from interviews with both TC staff and case study participants: guidance; training; and resources. The lack of detailed guidance to industry on how to properly implement an SMS within their company, combined with the lack of timely and comprehensive training for TC inspectors, contributed to the confusion surrounding regulatory interpretations for several years post-implementation. While this has improved over time, issues of inconsistent interpretation of regulations and confusion in the sector appeared to persist at the writing of this report.

Literature shows that SMS can result in cost savings, primarily through accidents and incidents averted. Case study interviewees supported this and provided examples of savings, such as reduced insurance premiums. However, it is not clear to what extent savings from SMS offset the cost of system implementation and maintenance.

Guidance and Training

Guidance Materials

Finding 9:

Organizations found that the guidance materials provided by TC during SMS implementation were unclear. Companies therefore turned to a variety of sources for guidance, training, and advice.

Overall, both TC and industry interviewees reported that SMS was introduced without proper preparation on both sides. Many interviewees felt that TC assumed that industry would figure SMS out on their own.

TC’s intention was for SMS implementation guidance materials to be useful for all sizes and types of organizations. In theory, providing more generalized guidance would encourage companies to design an SMS that fits their operational needs. However, in practice, industry key informants found the lack of specificity significantly limited the guidance’s usefulness. Both TC and industry interviewees stated that TC’s guidance materials were unclear and ineffectual.

Interviewees suggested that TC could provide more training for industry to ensure a consistent understanding of SMS and TC’s expectations. Among all interviewees, 43% (or 92% excluding the interviewees who provided no answer to this question) stated that TC could provide more training. From industry’s perspective, TC’s templates are not enough guidance to demonstrate how to develop and operate an SMS. Similarly, TC inspectors agreed that proper training and outreach for industry could reduce the burden on inspectors by filling in common information gaps. Alternatives to TC-led training include ensuring that pilot schools and technical training programs introduce SMS concepts to industry employees early on. Similarly, joint information or training sessions between TC and industry could ensure that there is a common understanding of SMS on both sides.

According to industry interviewees, the implementation process would have been smoother if TC offered clearly defined expectations for the SMS and examples of final products. In addition, industry felt that the guidance documents were written in complex language that was difficult to understand and interpret. Plain language, examples of SMS on paper, and templates would have assisted companies in knowing where to start. According to industry interviewees, implementation was a confusing process but in some cases was made easier thanks to specific TCCA teams and staff members.

Due to the generic nature of TC’s guidance materials, the evaluation’s survey results show that industry turned to training and advice from external consultants and events organized by industry associations to help fill gaps in information. In all, industry found that non-TC sources of information were more useful than TC’s documentation.

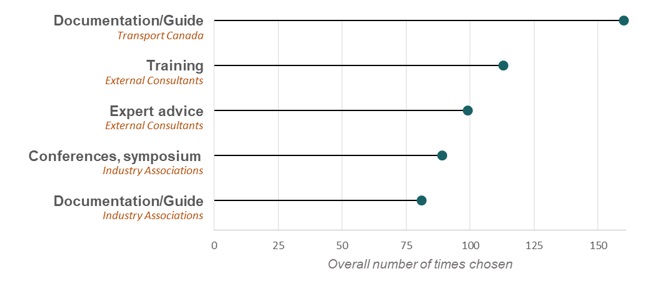

Figure 10: Overall top five guidance on the implementation of SMS received by organizations

Figure 10: Text version

This figure is a horizontal lollipop chart listing the top five types of guidance and their sources on the implementation of SMS received by organizations. The top bar shows that “documentation/guide from Transport Canada” was chosen over 150 times, “training from external consultants” was chosen between 100 and 125 times, “expert advice from external consultants” was chosen approximately 100 times, “conferences/symposiums by industry associations” was chosen between 75 and 100 times, and “documentation/guide from industry associations” was chosen over 75 times.

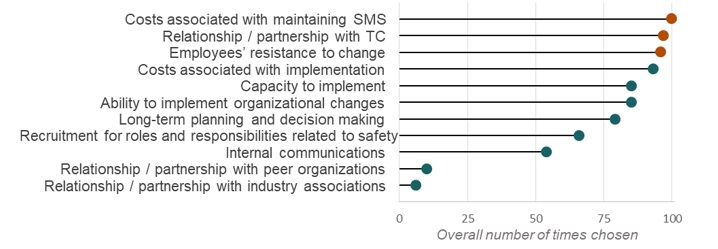

Figure 11: Overall ranking of sources of guidance on the implementation of SMS received by organizations

Figure 11: Text version

This figure is a horizontal lollipop chart listing the top five sources of guidance on the implementation of SMS received by organizations. The top bar shows that “external consultants” was chosen 327 times, “industry associations” was chosen 312 times, “Transport Canada” was chosen 292 times, “peer organizations” was chosen 181 times”, and “international associations” was chosen 107 times.

Industry personnel also relied on external consultants to help navigate SMS implementation. While some industry interviewees benefited from consultant support, others noted that hiring a consultant is extremely expensive and could easily lead to generalized processes and manuals that do not fit the company’s unique needs, which would negatively impact SMS effectiveness.

Training for TC Inspectors

Finding 10:

Training for TC inspectors lacks timeliness, depth, and consistency. There is no common understanding or application of SMS principles and inspection procedures.

The Auditor General of Canada noted in its May 2008 report that TC provided SMS training to inspectors and engineers in 2004 and 2005, and that “many took the training well before they could apply it. This limited the course’s effectiveness.”Footnote 34 The 2008 report also noted that “no regular recurrent SMS training has been planned.”Footnote 35 TC interviewees echoed the concern that their training during implementation was offered too far in advance of when they were expected to put their skills into practice.

Following up in 2012, the Auditor General reported that, “by the end of March 2011, a majority of inspectors had received mandatory training on the concepts and principles of SMS, on proactive interview skills, and on quality assurance. However, at that time, only 40 percent of inspectors had been trained on the new surveillance methodology. As a result, we noted that many inspections were carried out in 2010–11 by inspectors who had not received this training.”Footnote 36 When we conducted the evaluation in 2018, the issue of training was still a prominent concern among TC interviewees who felt that it was lacking, too superficial, and in some cases non-existent. There remained inspectors who felt ill-prepared to enforce the new regulatory requirements and, as has been previously stated, this led to inconsistent understandings among inspectors. In sum, this was a common problem during the implementation process, but concerns appear to persist in 2018.

TC interviewees noted that training opportunities have not grown, but have reduced from multi-day classroom sessions to e-learning formats. Some inspectors noted that it is difficult to confidently fulfill their top mandate activity of surveillance when there is no recurring training. Neither is there training to update inspectors on changes such as the introduction of targeted inspections, or updates to the surveillance program.

TC’s introduction of expectations in 2013 exacerbated already existing confusion over the implementation of judgement-based findings. TCCA introduced expectations in order to “define the intent of regulatory requirements”.Footnote 37 TC’s staff instructions noted that “there may be several ways for an enterprise to meet an expectation in an effective manner”.Footnote 38 Findings could be issued against regulations but not against expectations, however the expectations remained until 2018 and confused both inspectors and industry. From industry’s perspective, expectations added another layer of compliance that was not officially regulated by TC. The Auditor General of Canada agreed that SUR-001 “establishe[d] a vague policy with subjective guidelines and does not provide TC or carriers with clear and objective legal standards”.Footnote 39