Image Description - Map: National Transportation Infrastructure of Canada

The map shows Canada’s transportation network, i.e. air, marine, rail and road transportation networks. It shows each of the 26 airports of the National Airport System (NAS). Each airport, represented by a black plane in a white circle, is identified geographically to illustrate basic air infrastructure. Seven of these airports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, three in Québec, four in Ontario, six in the Prairie Provinces and three in British Columbia. Three other airports are found in the capital of each territory.

It also shows the approximate location of the 18 Canadian Port Authorities (CPA). Each is represented by an anchor in a blue circle. The CPA ports are (in alphabetical order): Belledune, Halifax, Hamilton, Montréal, Nanaimo, Oshawa, Port Alberni, Prince-Rupert, Québec, Saguenay, Saint John, Sept-Îles, St. John's, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Trois-Rivières, Vancouver Fraser and Windsor. Four of these ports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, five in Québec, five in Ontario and four in British Columbia.

The map of Canada also shows the layout and extent of the Canadian rail system. This system currently has over 45,000 route-kilometres of track. The network is illustrated by orange lines for a geographical representation of rail infrastructure.

Finally, it shows the location of the National Highway System (NHS). The NHS includes over thirty-eight thousand kilometers of Canada’s most important highways from coast to coast. It is illustrated by blue lines for geographical representation of basic road infrastructure.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Transport, 2018.

Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Les transports au Canada 2017, Un survol.

TP No. 15388 E

TC No. TC-1006006

Catalogue No. T1-21E-PDF

ISSN 1920-0854

Permission to reproduce

Transport Canada grants permission to copy and/or reproduce the contents of this publication for personal and public non-commercial use. Users must reproduce the materials accurately, identify Transport Canada as the source and not present theirs as an official version, or as having been produced with the help or the endorsement of Transport Canada.

To request permission to reproduce materials from this publication for commercial purposes, please complete the following web form:

www.tc.gc.ca/eng/crown-copyright-request-614.html

Or contact TCcopyright-droitdauteurTC@tc.gc.ca

An electronic version of this publication is available at https://www.tc.gc.ca/en/transport-canada/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/annual-reports.html

Table of contents

- Minister's Message

- Transportation 2030

- Highlights

- Report Purpose

- Chapter 1 The Role of Transportation in the Economy

- Chapter 2 Overview of Canada’s Transportation System

- Chapter 3 Air Transportation Sector

- Chapter 4 Marine Transportation Sector

- Chapter 5 Rail Transportation Sector

- Chapter 6 Road Transportation Sector

- Chapter 7 Transportation of Dangerous Goods

- Chapter 8 Performance of the Canadian Transportation System in 2017

- Chapter 9 Outlook, Trends, and Future Issues

- Annex A: Maps and Figures

- Annex B: List of Addendum Tables and Figures

Minister's Message

It is with great pleasure that I submit Transportation in Canada 2017, the annual report on the state of transportation in Canada.

A modern, safe and efficient transportation system that is environmentally responsible is necessary to the strength and competitiveness of Canada’s economy, and is also critical in ensuring the quality of life of all Canadians. Transportation is essential both for trade and businesses and for connecting people and communities.

In 2017, our transportation system met rising demand amid strong economic growth in Canada and in our key trading partners. Our overall safety record remains among the best in years even as flows of passengers and merchandise continue to grow. Our environmental initiatives have kept transportation-related greenhouse gas emissions down.

To ensure our system is better, smarter, cleaner and safer, the Government of Canada continues to work hard to implement our Transportation 2030 Strategic Plan. In May 2018, Bill C-49, the Transportation Modernization Act, received Royal Assent. It is a first step towards establishing new air passenger rights, providing travellers with more choice by increasing air carrier competitiveness, improving rail safety and sustainable long-term investment in the freight rail sector.

The Government of Canada also continues to deliver on its commitment to strengthen environmental protections by implementing the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, including carbon pricing measures, clean fuel standards, and a Canada-wide strategy on zero-emission vehicles. In addition, the Government has announced initiatives under the $1.5 billion Oceans Protection Plan to ensure that our coasts are protected in a modern and advanced way that ensures environmental sustainability, safe and responsible commercial use, and collaboration with coastal and Indigenous communities. Also of significance, the Government of Canada successfully implemented a vessel speed restriction in the Gulf of St. Lawrence through the summer and fall of 2017 to protect the endangered North Atlantic right whale population from further fatal vessel strikes.

In July 2017, we launched the Trade and Transportation Corridors Initiative (TTCI) to build stronger, more efficient transportation corridors to international markets. The core element of the TTCI is the merit-based National Trade Corridors Fund, which will provide $2 billion over 11 years to strengthen Canada’s trade infrastructure and support the flow of goods and passengers by reducing bottlenecks.

As part of this announcement, we also launched a Trade and Transportation Information System, supported by a new Canadian Centre on Transportation Data, to provide access to high-quality, timely and accessible information on our transportation system.

Transportation 2030 will continue to bring partners together to maintain Canada’s competitive advantage in its overseas markets and protect Canadian jobs. In addition, Transport Canada will continue contributing to the Government of Canada’s commitment to becoming a world leader in gender equity by applying gender equity principles to our transportation policies, programs and services.

I trust that this edition of the report and its supporting statistical addendum provide valuable information to better appreciate the significant importance of the transportation system in Canada, as well as the many exciting opportunities and challenges it presents.

Sincerely,

The Honourable Marc Garneau, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Transport

Transportation 2030

The Government of Canada’s Strategy for the Future of Transportation in Canada

Transport Canada continues to make progress in implementing the Transportation 2030 strategic plan. Transportation 2030 is based on 5 themes:

- the Traveller

- Green and Innovative Transportation

- Trade Corridors to Global Markets

- Waterways, Coasts and the North

- Safer Transportation

Transportation Modernization Act

In May 2018, the Transportation Modernization Act received Royal Assent. It is a first legislative step to deliver on early measures that are part of Transportation 2030.

The Act will improve the transportation system in the following ways:

- Create a clear set of rules about how airlines in Canada must treat passengers

- Changes to passenger airline ownership rules that should result in lower air fares

- Allow airports to pay for additional services to improve the security screening experience for passengers

- Put recording devices locomotives to provide information about railway accidents

- Allow foreign ships to move empty containers between places in Canada without a special licence

- Allow Canadian Port Authorities to access funding from the Canada Infrastructure Bank

Transport-related Initiatives

A number of actions have been initiated, or are in development, to support a safe, secure, innovative and integrated transportation system that promotes trade, economic growth, a cleaner environment and greater consideration to gender and diversity outcomes.

The Oceans Protection Plan

$1.5 billion over eleven years to improve marine safety and responsible shipping, protect Canada’s marine environment, and offer new possibilities for Indigenous and coastal communities

National Trade Corridors Fund

$2 billion over 11 years to make Canada’s trade corridors more efficient and reliable

Modernize Canada’s Transportation System

Developing strategies, regulations and pilot projects for the safe adoption of connected and autonomous vehicles, and unmanned aircraft systems

Trade and Transportation Information System

Supporting evidence-based decision making by filling data and analytical gaps, strengthening partnerships, and increasing transparency regarding strategic transportation information

The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change

Supporting the development of measures including the federal carbon pricing benchmark, the clean fuel standard, and a national Zero-Emission Vehicle Strategy

For more information on our progress visit: tc.gc.ca/eng/future-transportation-canada.html.

Highlights

Government of Canada Actions

Transport Canada continues making progress in implementing initiatives under Transportation 2030. In May 2018, the Transportation Modernization Act received Royal Assent. This is an important legislative step toward improving the air passenger experience as well as the safety and efficiency of the rail system.

In addition, other initiatives continue to be implemented including the Oceans Protection Plan, the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, the Trade and Transportation Corridors Initiative, which includes the Canadian Centre on Transportation Data.

To further improve the safety of the Canadian transportation system in 2017, the Minister of Transport launched the Statutory Review of the Railway Safety Act, introduced the Transportation Modernization Act and is strengthening the Motor Vehicle Safety Act. Safety in the transportation of dangerous goods was also strengthened across Canada through increased inspections, regulations updates, and outreach and awareness to stakeholders. Canada also continued its work to facilitate the flow of legitimate passengers and freight while maintaining a high level of security through inspections, information sharing and stakeholder engagements.

Through the summer and fall of 2017, the Government of Canada also successfully implemented a vessel speed restriction zone for large vessels passing through a large portion of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This action substantially reduced the risk of fatal vessel strikes for the endangered North Atlantic right whale population that resided in the area during this period.

In 2017, the Government of Canada continued its efforts to ensure transportation is increasingly environmentally responsible through different measures including: work on the development of a Canada-wide strategy for zero-emission vehicles in collaboration with provincial and territorial governments, the implementation of carbon dioxide standards for new airplanes, the publishing of draft greenhouse gases (GHG) regulations for heavy duty road vehicles, the development of the Locomotive Emission Regulations, and the entry into force of the Ballast Water Control and Management Regulations.

In 2017, the Government of Canada also announced a number of measures through the Oceans Protection Plan’s initiatives to strengthen environmental protection, prevent marine incidents and improve emergency response capacity.

Transportation Volumes and Performance

Global economic growth was relatively strong in 2017, with accelerating growth observed in most major economies. In Canada, this stronger than expected worldwide economic growth translated into higher merchandise flows both to and from international markets, resulting in higher demand for transportation services.

Both, the volume of international air cargo and trucking activity to and from the U.S. increased in 2017.

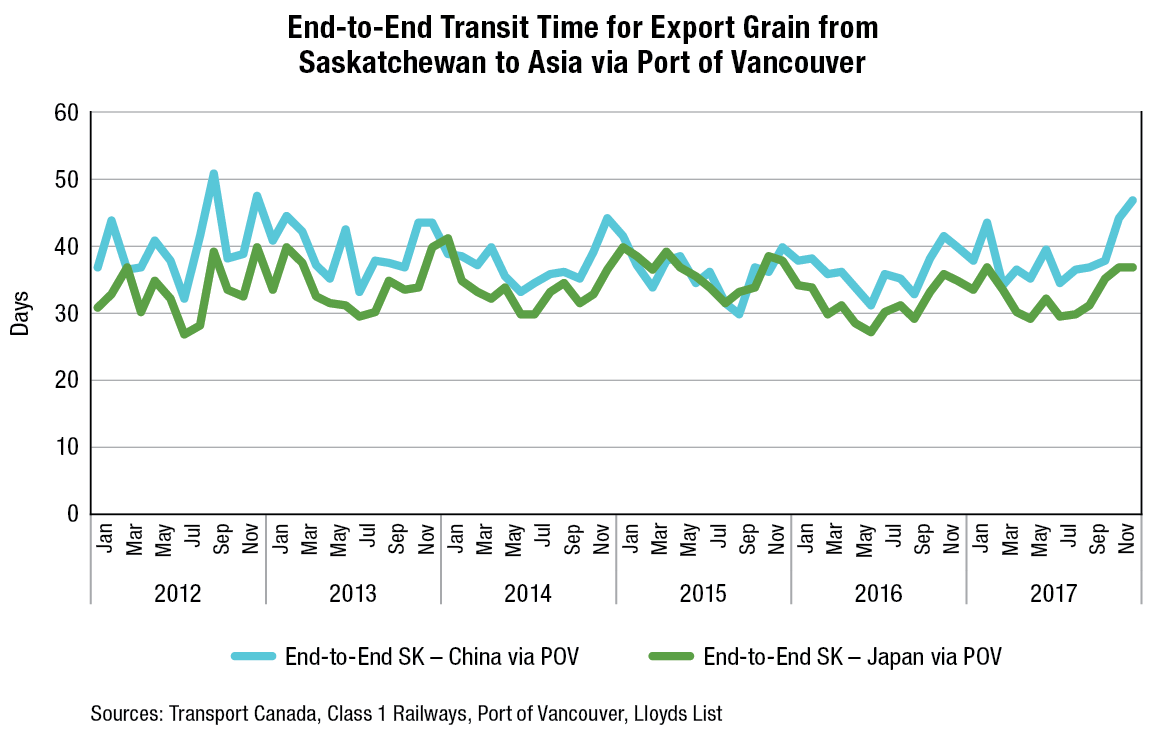

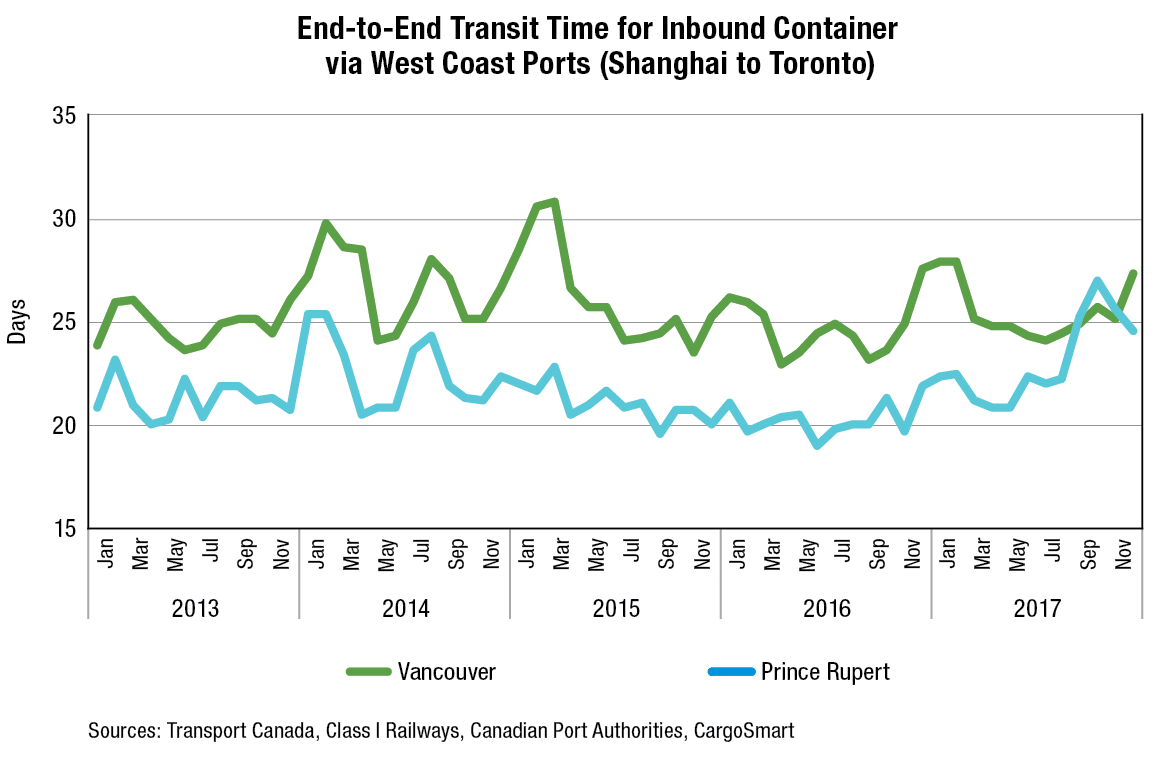

Total rail freight tonnage moved increased in 2017 after having declined in 2016, with notable growth in key commodities such as petroleum products, potash, containers, grain, coal, metals and iron ore. Similarly, the value of international waterborne traffic also increased, as did volumes handled at most major Canadian ports (Vancouver, Prince Rupert, Montréal and Halifax).

Despite higher than expected transportation demand in 2017, marine and surface freight transportation was relatively fluid overall for most of the year, moving increased volumes on time. However, harsh winter conditions, combined with capacity challenges experienced by some railways, and construction at the Port of Vancouver and Prince Rupert, did hamper performance. This resulted in fluidity and congestion issues toward the end of the year throughout Western Canada, notably in the Lower Vancouver Mainland area. Partners are collaborating to ensure better coordination and planning to address emerging capacity and performance challenges.

The number of international passengers moved across all modes set a new record high during Canada’s 150th anniversary celebration year of 20.8 million trips of one or more nights, surpassing the previous record set in 2002. The volume of air passengers travelling on domestic and international flights recorded solid gains compared to 2016.

Environment, Safety and Security

GHG emissions have decreased since 2006 from air transportation due to improved fuel efficiency and from marine transportation due to declining traffic as shippers shift to other modes. In contrast, emissions from rail and road transportation, the latter accounting for 85% of all transport-related emissions in Canada, have increased over the same period, mostly due to increased traffic.

Canada continues to have one of the safest and most secure transportation systems in the world. The total number of aviation and rail accidents rose in 2017, while it declined for the marine and road sectors. The number of accidents however remained close to, or lower than, the 10-year average for all modes.

Transportation Outlook

Ongoing and emerging socio-demographic, technological and environmental trends will require governments and stakeholders to continuously adapt in order for the transportation system to remain competitive, resilient, safe and secure.

Looking ahead, developing markets are expected to be the primary engine of growth, while growth prospects for Canada’s other major trading partners, which include industrialized nations, will be facing the consequences of aging populations (e.g., lower labour force participation rate) leading to expectations of lower demand for Canadian products. Over the near to medium term, transportation demand for Canadian commodities is projected to be high due to an improved economic climate, despite North American trade uncertainty. The number of air passengers in Canada should continue rising over the next decade, with the strongest increase in international passengers (i.e., other than the U.S.) and growth from emerging markets. However, moderate domestic economic growth and adverse demographics, including an aging and slowly growing population, are expected to moderate growth in domestic demand for air passenger transportation.

Report Purpose

As mandated by the Canada Transportation Act of 2007, subsection 52, each year the Minister of Transport must table in both Houses of Parliament an overview of the state of transportation in Canada.

In this report, the 11th edition submitted by the Minister under the Act, readers will find an overview of transportation in Canada based on the most current information available for all modes at the time of publication.

The report highlights the role of transportation in the economy and provides an overview of the four transportation modes (air, marine, rail, road) in terms of infrastructure, safety and security, and environment, as well as major industry and policy developments in the transportation sector over the course of 2017. It also presents a short overall assessment of the performance of the Canadian transportation system in 2017, looking both at the use and the capacity of the system. The report concludes with an outlook on expected trends in freight and air passenger transportation.

Canadian Center on Transportation Data

While transportation stakeholders require access to high quality, timely and accessible information to support innovations that will move goods more efficiently across supply and distribution chains, providing an understanding of the state of transportation in Canada is impaired by the lack of timely, relevant and consistent system-wide data.

Following the Government of Canada’s commitment to improve access to, and availability of, data and information on transportation in its 2017 Budget, Transport Canada and Statistics Canada jointly launched the new Canadian Centre on Transportation Data (CCTD) in April 2018.

Along with other participating stakeholders, including provinces, territories, academia and industry, the CCTD now represents, along with Transport Canada’s annual report and statistical addendum, a comprehensive and authoritative source of multimodal transportation data and performance measures.

New Transportation Data Hub

Through a new data hub, the CCTD now provides easy access to a comprehensive, timely and accessible source of multimodal transportation data and transportation system performance measures. This includes maps, analysis and data from different transportation stakeholders, as well as a first national transportation performance dashboard and access to the data in the annual statistical addendum in electronic form. This hub will be continuously developed to add new and relevant content that is useful to the transportation community. The longer term goal is to share information that will contribute to effective decision-making in Canada so as to take full advantage of the transportation system to support a strong economy.

Supply Chain Visibility Projects

Transport Canada continues to invest in multi-stakeholder partnership projects on supply chain visibility. After investing more than $2 million to support trucking visibility at the terminal gates of the Ports of Vancouver, Montréal and Halifax, Transport Canada is building on those initial investments and in 2017 announced a $250,000 contribution to the initial phase of a supply chain visibility project at the Port of Vancouver.

This project will provide access to real-time information on the grain and fertilizer supply chain performance for rail cargo moving to and from the Port of Vancouver. This information will support rail network planning and infrastructure decisions to further develop trade movements and contribute to higher volumes of trade. Other multi-stakeholder visibility projects are in development in:

- Montréal, to maintain the efficiency of the supply chains and efficient connectivity between the modes through better collaboration and data exchange between the partners;

- Toronto, on the development of an e-commerce collaborative platform in partnership with the Ministry of Transportation of Ontario and the Peel region; and,

- Halifax, to explore with the port and airport the opportunities to increase agri-food export trade from the region.

Forecasting

As part of the Trade and Transportation Information System initiative announced in Budget 2017, Transport Canada will be expanding its forecasting in order to include the development of long-term freight transportation demand forecasts based on economic drivers. Expansions will include:

- Developing annual forecasts of transportation demand for key supply chains and containers, by mode of transport for each of the key trade routes;

- Expanding the coverage of air passenger forcasts and developing intercity rail and road passenger forecasts.

Specific examples of how these forecasts would support Government of Canada initiatives include infrastructure project evaluation, assessment of future dangerous goods shipments and measurement of fuel and pollutant emissions linked to freight movements.

Chapter 1 The Role of Transportation in the Economy

Highlights

- The transportation and warehousing sector’s GDP increased 4.8% in 2017, 1.5 times the growth rate for all industries

- Aggregate household expenditures on transportation (including insurance in 2017) amounted to $194.8 billion– second only to shelter

- In 2017, total international trade increased by 5.4% to $1,107 billion

The Transportation Sector

Transportation and warehousing is important to the Canadian economy, representing 4.6% of total gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017. This sector grew by 4.8% in real terms in the past year, nearly 1.5 times the growth rate for all industries. The compound annual growth rate for GDP in the transportation sector over the previous five years of 3.3% also exceeds that of the economy as a whole (1.9%).

In 2017, 905,000 employees (including self-employed people) worked in the transportation and warehousing sector, up 0.9% from 2016.

Employment in commercial transport industries accounts for about 5% of total employment, a share that has remained stable over the past two decades. There were approximately 1.8 unemployed people with relevant work experience for every vacant job in the sector, compared to a ratio of 4.9 for the overall economy.

Transportation and the Economy

GDP measures only the economic activities directly linked to for-hire or commercial transportation. However, the importance of transportation is broader as it is also integral to other activities that are not included in economic measures, such as the value of personal travel.

In 2017, aggregate household final consumption expenditures on transportation (including insurance) amounted to $194.8 billion, second only to shelter in terms of major spending categories. Household spending for personal travel accounted for about 11% of GDP. Furthermore, federal and provincial government expenditures on infrastructure represented just under 1% of GDP.

The value of interprovincial merchandise trade totaled $152 billion (current dollars) in 2016, up 0.9% from 2015.

Transportation and International Trade

Transportation is a necessary element of Canada’s trade with other countries. In 2017, total international merchandise trade amounted to $1,107 billion, a 5.4% increase compared to 2016 and the highest value of total trade recorded. The U.S. remains Canada’s top trade partner, with $703 billion in total trade ($415 billion exported, $288 billion imported), up 4.5% from 2016. The U.S. accounted for 63% of total Canadian trade in 2017.

In addition to the U. S., Canada’s top 5 trading partners in 2017 included China, Mexico, Japan and the United Kingdom. The latter four nations accounted for 17.5% of Canada’s total international trade in 2017, surpassing the 17.0% recorded in 2016 as the new high mark for this group. They have also remained constant as Canada’s second through fifth trading partners over the past six years.

Canadian Transportation Economic Account

- As part of the Trade and Transportation Information System initiative, Statistics Canada in collaboration with Transport Canada, released the Canadian Transportation Economic Account (CTEA) in March 2018.

- The CTEA provides better estimates of the importance of transportation services produced in the Canadian economy. The CTEA provides desegregated information by mode and industry, and allows users to distinguish between for-hire and own- account services.

- According to the CTEA, output for total transportation activity was estimated to be $127.6 billion in 2013. Own-account transportation activity in air, rail, water and trucking collectively constituted 32% of overall transportation. Wholesale trade, manufacturing, retail trade, mining and construction together represented about 65% of the total own-account transportation activity.

- In the future, Statistics Canada will work to develop a measure of transportation use for the household sector by mode to better measure the impact of investments on various transport modes, including urban transit and passenger rail transportation.

Chapter 2 Overview of Canada’s Transportation System

Inefficiencies or vulnerabilities in Canada’s national transportation system have the potential to constrain national economic growth. Budget 2017 detailed the Government’s 11-year, $186 billion Investing in Canada infrastructure plan. The Plan will invest $10.1 billion in national trade and transportation infrastructure to provide a foundation for long-term national economic growth, support job creation, and position Canada as an attractive investment opportunity for international investors.

In 2017, the Government also established the Canada Infrastructure Bank as an arm’s-length organization that will work with provincial, territorial, municipal, Indigenous, and private sector institutional investment partners to build infrastructure across Canada. The Canada Infrastructure Bank will invest strategically, alongside private and institutional investors, with a focus on large revenue-generating projects. The Canada Infrastructure Bank has been allocated $35 billion over 11 years, including at least $5 billion for trade and transportation infrastructure.

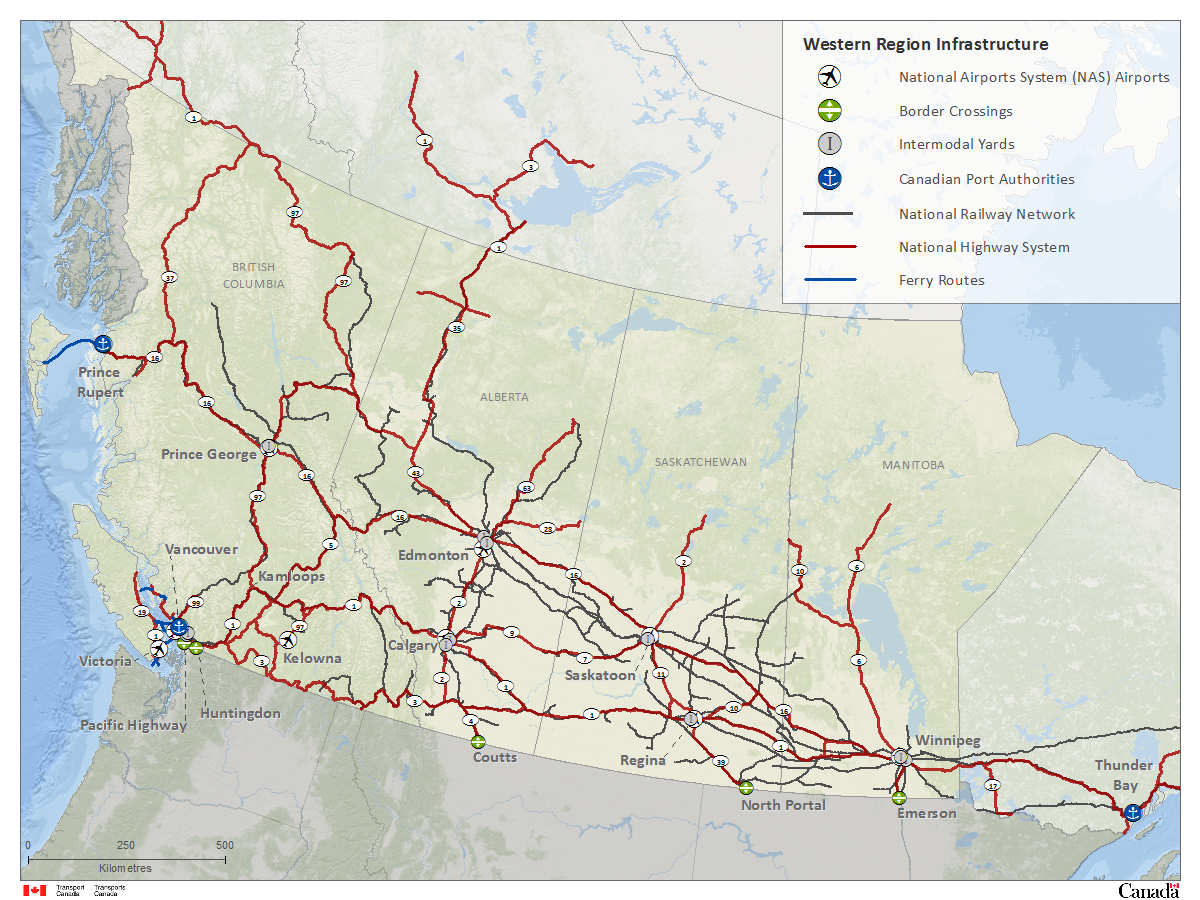

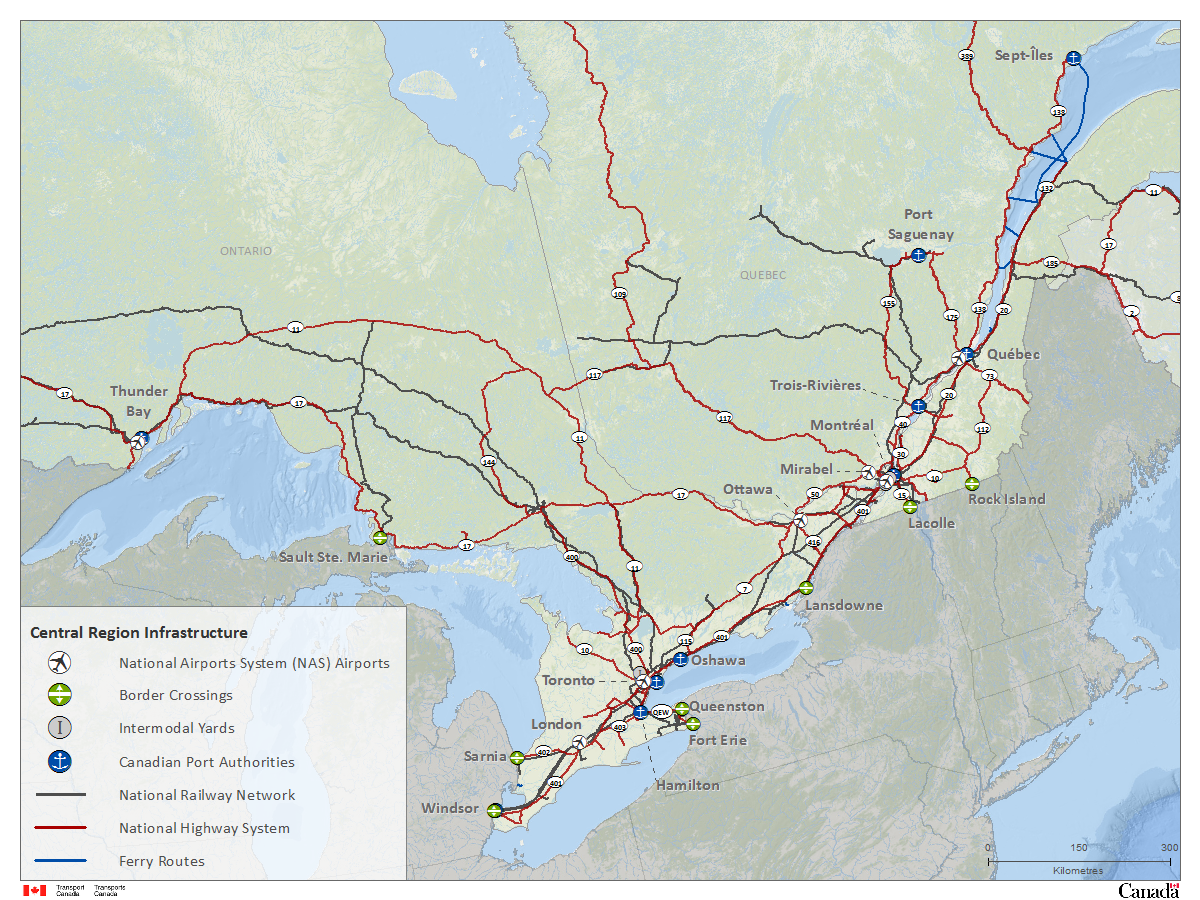

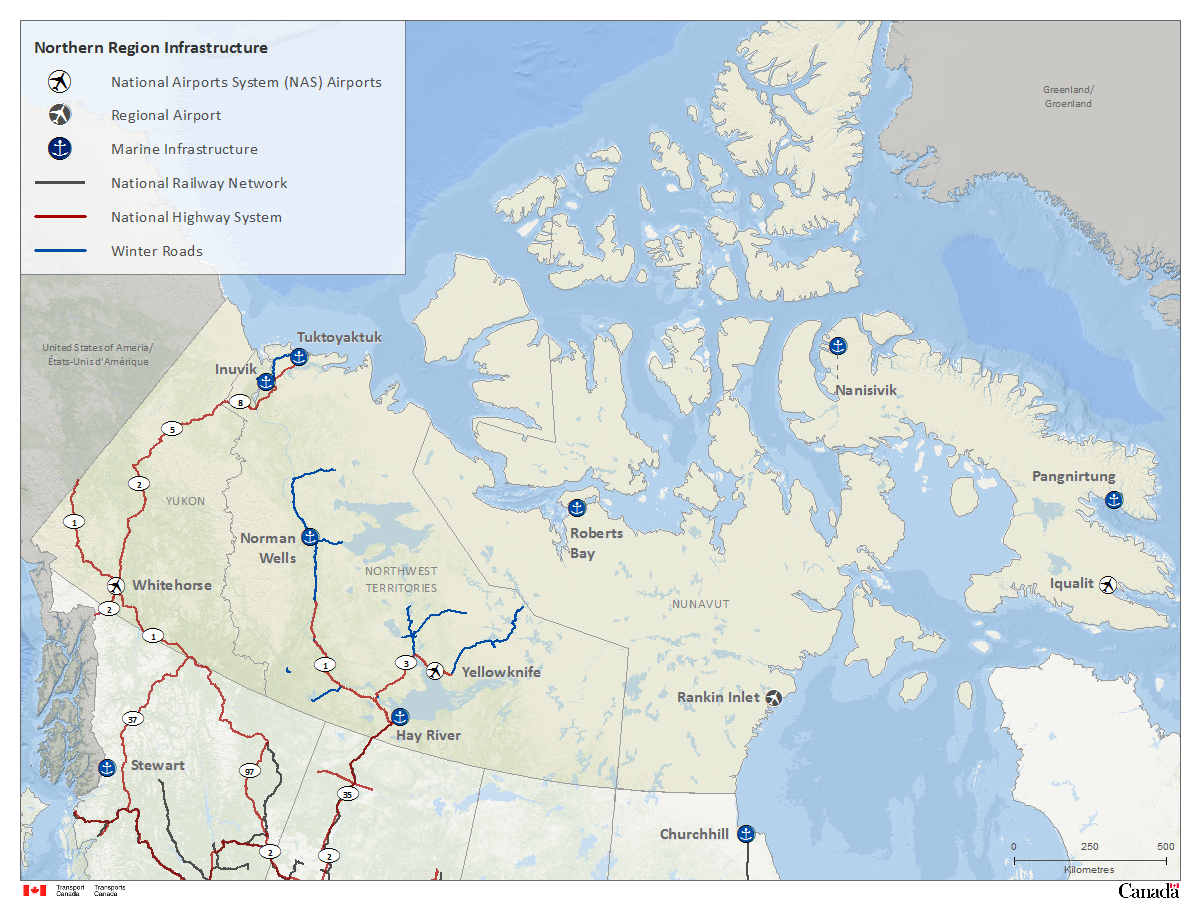

Canada’s National Transportation Network

With a land area of close to 10 million km2, Canada is the second largest country in the world. With such a large territory, the transportation network must reliably span large distances and varying topography in order to reliably support the movement of passengers and freight across the country and internationally. Canada’s vast and varied geography means that different regions within the country have had to develop distinct solutions to their transportation challenges (see Regional Maps, 1 to 4, in Annex A).

Canada’s national road transportation system

Canada transportation system is primarily based on road transportation, both for passengers and freight. The country is connected from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic and Arctic coasts by a network of highways anchored by the Trans-Canada Highway (TCH), and has extensive road networks across the southern, more populated, portions of the country.

Trucking is the primary form of freight transportation, especially in central Canada where it is primarily used for moving food products and manufactured and other processed goods. Ontario and Québec also have the busiest road border crossings in Canada, especially in the Ontario region where manufactured goods will cross and re-cross the border with the U.S. several times throughout the production process. In central Canada, 55% of total merchandise exports by value, excluding pipelines, were exported by road in 2017. This is compared to 32% and 21% in the Western and Atlantic regions of Canada, respectively, which rely more on marine transportation.

Yukon has the most extensive highway system in northern Canada carrying the most northern traffic in tonnage terms, at over 40% of total tonnage in the region. The all-weather northern highway system has also recently been extended to Tuktoyaktuk, on the Arctic coast in the Northwest Territories. Northern communities also rely on a network of ice roads to transport people and cargo during the winter.

Canada’s national rail transportation network

Two major freight railways, Canadian National and Canadian Pacific, and a number of short line railways are instrumental in transporting containerized merchandise and bulk resources to and from major ports and to the U. S..

Passenger rail services provided by Crown-owned VIA Rail operate mostly in Central Canada along the Québec-Windsor Corridor. VIA Rail also operates long-haul passenger routes between Toronto and Vancouver, and Montréal and Halifax, as well as regional services, including Jasper and Prince Rupert, Winnipeg and Churchill. In 2017, VIA Rail transported a total of 4.4 million passengers.

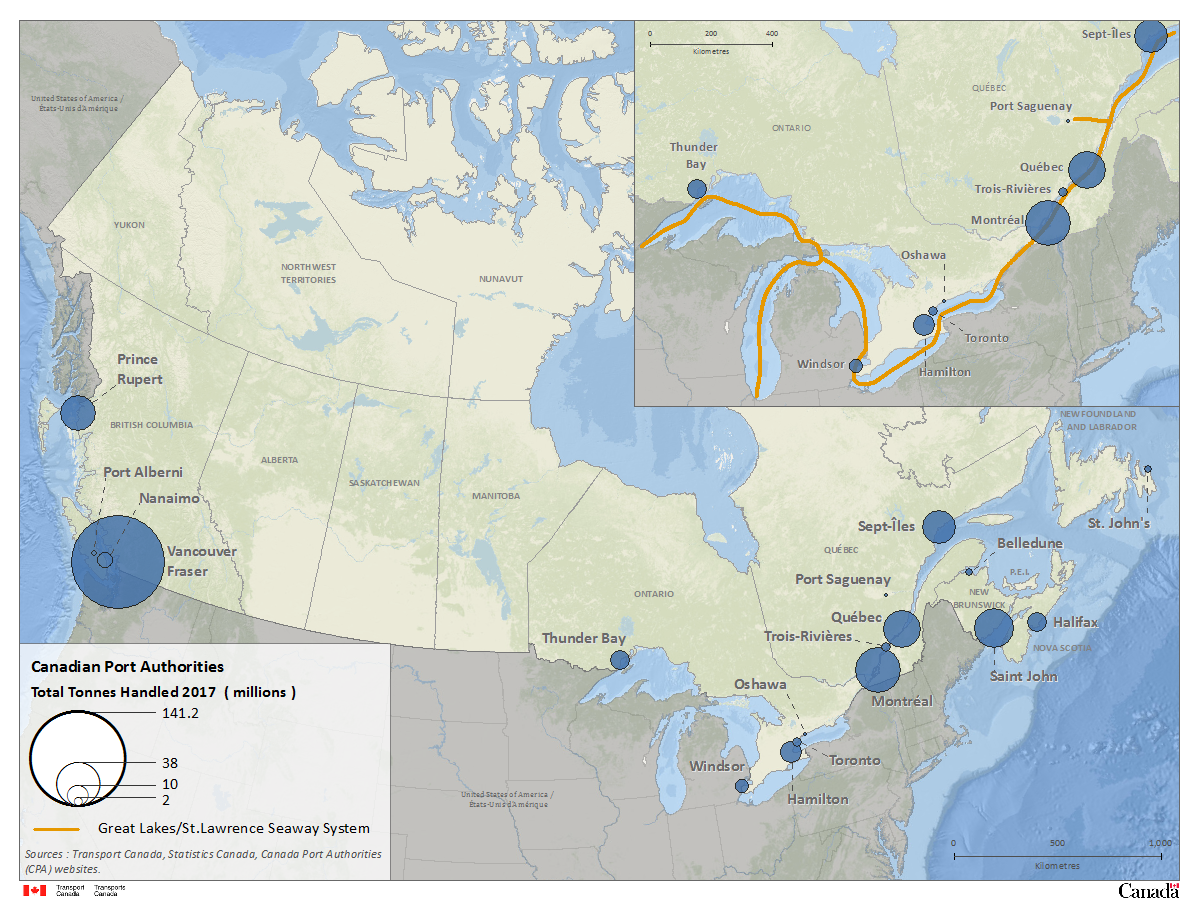

Canada’s marine transportation network

Canadian ports are the main point of entry for imported containerized manufactured goods. These goods are then shipped to the rest of the country or transshipped to the U.S. by railways and trucks.

The Port of Vancouver in western Canada is Canada’s largest port in terms of traffic volume. It handled 142.1 million tonnes (Mt) of traffic in 2017, predominantly destined for and arriving from Asian markets. The Port of Prince Rupert, another important port on the West coast, handled 24.1Mt in 2017, also linked to Asian markets.

The Port of Montréal in central Canada is Canada’s second largest container port. It mainly serves Québec, Ontario and the U.S. Midwest. In 2017, the port handled more than 38Mt of cargo from around the world, but most predominantly Europe.

Marine transportation activities are also high in the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence Seaway (“the Seaway”), which provides waterway access into central Canada and the North American heartland. The Seaway serves 15 major ports and 50 regional ports that connect to more than 40 provincial or interstate highways and 30 railway lines. In 2017, 10.2Mt of grain was moved through the Seaway. In 2017, other commodities of importance to Seaway traffic included iron ore (8.2Mt), coal (2.3Mt) and petroleum products (2.7Mt).Footnote 1

The Port of Halifax is the largest container port in Atlantic Canada and handles most of the region’s trade with 4.6Mt of containerized cargo traffic in 2017. Petroleum products and vehicles also represent an important part of the port activities. In addition, the Port of Saint John in New Brunswick is Atlantic Canada’s largest port, handling 30.5Mt of cargo annually. It is an important port for the processing, refinement and shipment of crude oil. The port of Come-by-Chance in Newfoundland and Labrador also mainly handles petroleum products from the province’s offshore oil project sites.

Many remote northern communities are highly dependent on seasonal sealifts for their bulk transportation needs. With limited permanent port facilities in these small communities, this sealift system is limited to shallow draft barge docks.

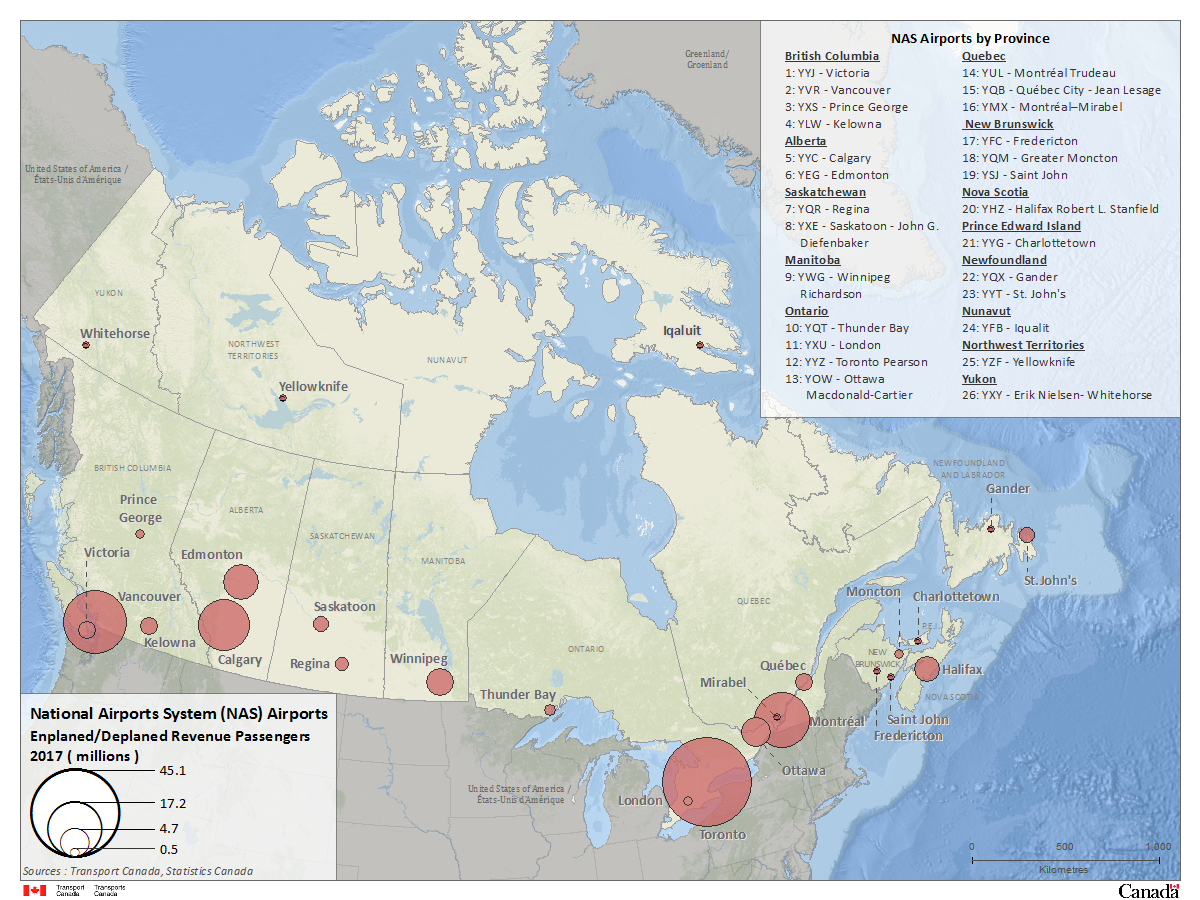

Canada’s national air transportation network

Canada’s air transportation system is an important means of efficient passenger movement across a country spanning six time zones, and to destinations around the globe. Major airports include Toronto’s Pearson Airport, Canada’s busiest, moving 45.1 million passengers in 2017, Vancouver International which handled 23.6 million passengers and Montréal’s Trudeau, which handled 17.2 million passengers. In 2017, the top 20 Canadian busiest airports moved 134.5 million passengers.

International airports in each major city also provide cargo services to domestic and international markets. Major cargo airports included Toronto Pearson International (444.6 thousand tonnes), Vancouver International (286.1 thousand tonnes), and Hamilton (99.2 thousand tonnes).

Air transportation is also crucial in Canada’s remote northern regions where road or marine access is seasonal or non-existent for travel, essential services such as medical emergencies, all-season resupply including food and mail, tourism, and other economic development. The northern air system has scheduled air carriers which provide mainline services between southern Canada and an extensive network of connecting or feeder services across the North.

National Trade Corridors Fund

- The centerpiece of the National Trade Corridors Initiative is the $2 billion, 11 year, National Trade Corridors Fund (NTCF), which was launched in July 2017.

- Building on Canada’s previous gateways and trade corridors programming, the NTCF will be nationally delivered and consist of competitive, merit-based calls for proposals. The first call for proposals was run in 2017. The NTCF will invest to address urgent capacity constraints and freight bottlenecks at major ports of entry, and to better connect the rail and highway infrastructure that delivers economic growth across Canada. NTCF projects will also help the transportation system withstand the effects of climate change and make sure it is able to support new technologies and innovation.

- In addition to focusing on facilitating international trade and getting Canadian goods to market, the NTCF has a dedicated allotment of up to $400 million to address critical transportation needs in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon. Northern investments will improve the flow of supplies to communities, foster economic and social development, and enhance safety.

Challenges for the Future in Canada’s Transportation System

Canada’s vast and varying geography and sometimes harsh climate make it a challenging and expensive environment in which to operate transportation services. When these factors are taken together with the evolution of trade and travel patterns across Canada and to the rest of the world, certain parts of today’s transportation system are critical to the stable operation of multiple supply chains and passenger travel.

The Port of Vancouver is both the preferred point of exit for many of Canada’s exporters of bulk commodities from western Canada and the preferred point of entry for many importers of containerized goods into central Canada. This prominence in so many important national supply chains makes the efficient operation of the Port of Vancouver a matter of national interest. This high volume of traffic combined with the density of urban development in the surrounding area makes transportation operations around the port facilities challenging, with high risk of congestion that can unbalance supply chains across Canada.

Between Canada’s Pacific Coast and inland Canada, both the Trans-Canada Highway and Canada’s railroad infrastructure must cross the Rocky Mountains, one of the longest mountain chains in the world with the Canadian portion spanning close to 1,500 km. The railroads have had to adapt their operations to suit this challenging terrain. However, in the Fraser Canyon, within a 10 km rail stretch in British Columbia, rail operations are particularly susceptible to weather events that can severely disrupt rail access between the Vancouver lower mainland and the rest of Canada, with consequential impacts on all of the supply chains that depend upon this access.

Central Canada is a highly populated chain of urban areas, particularly between Windsor through Toronto and Montréal, up to Québec City. This area is well integrated by road networks to neighbouring American urban areas from Detroit, Michigan, to the northeastern U.S. Canada’s urban agglomerations, including as well high urban concentrations in the lower mainland of British Columbia around Vancouver, and in Calgary and Edmonton in Alberta, share the same traffic congestion challenges as other urban areas around the world. Urban congestion imposes significant costs on the national economy in terms of both lost productivity due to excessive commuting times and lost efficiency due to challenges in completing the first or last mile of supply chains.

Climate change is affecting transportation infrastructure across Canada, as elsewhere in the world. With rising temperatures in the Arctic, the conventional approach of constructing ice roads to support winter community travel and resupply is being challenged by shorter seasons and less reliable weather conditions. More variable weather, particularly freeze-thaw cycles that destabilize terrain or fast winter melts that cause flooding, can disrupt both road and rail transportation. Rising sea levels, and heightened storm surges can also compromise transportation infrastructure, such as in the Chignecto Isthmus that connects Nova Scotia to the rest of the country by road and by rail.

Chapter 3 Air Transportation Sector

Image Description - Map: Air Transportation Network

The map of Canada shows the 26 airports of the NAS. Each airport, represented by a black plane in a white circle, is identified geographically to illustrate basic air infrastructure. Seven of these airports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, three in Québec, four in Ontario, six in the Prairie Provinces and three in British Columbia. Three other airports are found in the capital of each territory.

Highlights

- Canada concluded expanded agreements with several markets, including Ethiopia, Israel, Qatar, Thailand, and South Africa, as well as a first-time agreement with Cameroon

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection pre-cleared around 13 million U.S. bound passengers at Canada’s eight preclearance airports under the current Agreement on Air Transport Preclearance

- The sector has been improving fuel efficiency through voluntary measures under signed agreements with the Government of Canada since 2005

Industry Infrastructure

Canada is the third largest aerospace sector in the world, and has 18,000,000 kilometres (km)2 of airspace managed by the second largest Air Navigation Service provider in the world, NAV CANADA.

NAV CANADA is a privately run, not-for-profit corporation that owns and operates Canada’s civil air navigation system. It operates air traffic control towers at 41 airports and flight service stations at 55 airports. Map 5 in Annex A is a detailed representation of National Airport System Airports.

The Canada Flight Supplement and the Canada Water Aerodrome Supplement listed 1,572 certified and registered sites in 2017. They fall into three categories:

- 223 water aerodromes for float and ski planes;

- 346 heliports for helicopters; and,

- 1,003 land aerodromes for fixed-wing aircraft.

Industry Structure

In 2017, 6.4 million aircraft movements took place at airports, 3.7 million of which were made by airlines. The other 2.7 million movements were itinerant and local movements made by general aviation companiesFootnote 1.

There were 36,588 Canadian registered aircraft, 68,812 licensed pilots, and 2,213 licensed authorities held by 1,425 air carriers operating in Canada (42% Canadian and 58% foreign) in 2017.

Canada had 17,658 aircraft maintenance engineers, 1,001 approved maintenance organizations, and 517 certified and 1,055 non-certified aerodromes in 2017.

Air Canada

In 2017, Air Canada, Air Canada Express and Air Canada Rouge together accounted for 55% of available seat- kilometres in the domestic air marketFootnote 2.

Air Canada, Air Canada Express, and Air Canada Rouge operated on average 1,602 scheduled flights per day. The Air Canada network has three hubs (Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver) and provided scheduled passenger services to 64 Canadian destinations, 57 U.S. destinations and 96 other foreign destinations on six continents.

As of December 2017, Air Canada had a fleet of 175 aircraft, while Air Canada Express was using 156 aircraft, and Air Canada Rouge operated 49 aircraft.

WestJet

In 2017, WestJet and WestJet Encore together accounted for 37% of available seat-kilometres in the domestic air market.

WestJet and WestJet Encore operated on average 675 scheduled flights per day. They provided scheduled passenger services to 39 Canadian destinations, 28 U.S. destinations and 34 destinations in the Caribbean and Mexico. In December 2017, WestJet had a fleet of 123 aircraft, while WestJet Encore had a fleet of 43 aircraft.

Other Carriers

In 2017, Porter Airlines, a regional carrier based at Toronto’s Billy Bishop airport, used a fleet of 29 turboprop aircraft to provide direct, non-stop scheduled passenger services to 21 destinations in Canada and nine in the U.S.

Air Transat was the largest leisure carrier in Canada for 2017, with a fleet of up to 40 aircraft, depending on the season, serving 65 international destinations in 26 countries.

Sunwing Airlines is Canada’s second largest leisure carrier. It operates a fleet of up to 30 aircraft, depending on the season, serving 32 international destinations in 11 countries.

In 2017, four ultra-low cost carriers, Enerjet, Canada Jetlines, Flair Airlines, and Swoop announced their intentions to start or expand service in 2018. As well, a new air carrier, FlyGTA Inc., introduced local scheduled air taxi services connecting Toronto to points in southern Ontario.

In 2017, foreign operators offered 12.8 million scheduled seats from Canada on an average of 273 flights per day. This is up from the 12.7 million seats offered in 2016.

As of December 2017, Canada had air transport agreements or arrangements with over 100 bilateral partners. In 2017, Canada concluded expanded agreements with several markets, including Ethiopia, Israel, Qatar, Thailand, and South Africa. A first-time agreement was also concluded with Cameroon.

Safe And Secure Transportation

Transport Canada delivers approximately 120,000 Civil Aviation services per year. In 2016-17 the Department delivered 24,846 pilot or flight engineer licensing requests, 1,107 air operator certificates, 6,108 Aircraft Registration requests, 47,053 Medical Assessments, 3,208 unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) Special Flight Operating Certificates, and thousands of inspections.

In 2017, U.S. Customs and Border Protection pre-cleared approximately 13 million U.S.-bound passengers at Canada’s eight preclearance airports under the current bilateral Agreement on Air Transport Preclearance. Once the new bilateral Land, Rail, Marine and Air Transport Preclearance Agreement (LRMA), signed in 2015, comes into force for each mode, it will be possible to expand preclearance to the land, rail and marine modes and to new locations in the air mode. The enabling legislation, the Preclearance Act, 2016, received Royal Assent on December 12, 2017, and will enter into force once the associated regulations are in place and the new agreement is ratified. Implementation will be phased in starting with the air mode.

Green And Innovative Transportation

The sector has been improving aviation fuel efficiency through voluntary measures under signed agreements with the Government of Canada since 2005. The latest agreement, signed in 2012, is Canada’s Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Aviation. The Action Plan sets a target to improve fuel efficiency by a 1.5% annual average until 2020 from a 2008 baseline.Footnote 3

In 2016, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) agreed on a new Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Standard for airplanes. The new standard will take effect in 2020 for newly designed airplanes and be phased in from 2023-2028 for in-production airplanes. The CO2 Standard addresses emissions at the source and is projected to cut emissions globally by 650 million tonnes over 2020-2040.

In 2016, the ICAO also agreed to implement a global market-based measure to reduce GHG emissions from international civil aviation, the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). Under CORSIA, airplane operators with emissions over 10 000 tonnes from international flights will be required to purchase acceptable emission units, primarily from other sectors to offset the growth of emissions in international aviation from 2020.

Canada has signed on to CORSIA from the outset, with monitoring, reporting and verification of emissions set to begin in 2019, and the offsetting component in 2021.

Chapter 4 Marine Transportation Sector

Image Description - Map: Marine Transportation Network

The map of Canada shows the approximate location of the 18 CPA. Each is represented by an anchor in a blue circle. The CPA ports are (in alphabetical order): Belledune, Halifax, Hamilton, Montréal, Nanaimo, Oshawa, Port Alberni, Prince-Rupert, Québec, Saguenay, Saint John, Sept-Îles, St. John's, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Trois-Rivières, Vancouver Fraser and Windsor. Four of these ports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, five in Québec, five in Ontario and four in British Columbia.

Highlights

- As part of the Oceans Protection Plan, the Government has been announcing initiatives worth more than $1.5 billion to restore and preserve marine ecosystems, strengthen partnerships with Indigenous communities, and invest in evidence-based emergency preparedness and response

- Investments in port infrastructure have helped Canadian Port Authorities to diversify their services as well as open up access to new global markets

- Transport Canada temporarily implemented a speed restriction for vessels in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to reduce the risk of incidents with North Atlantic right whale

- The International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments including sixty-seven countries, came into force

Industry Infrastructure

The Canadian Port System

Ports and harbours offer vital connections to support domestic and international economic activity. As of December 2017, Canada had 559 port facilities and had 866 fishing harbours and 129 recreational harbours.

Transport Canada has the mandate for two categories of ports: 18 ports independently managed by Canada Port Authorities (CPAs), shown on Map 6 in Annex A, and 47 port facilities currently owned and operated by Transport Canada.Footnote 1

Investments in new and existing port infrastructure have helped CPAs to diversify their services as well as open up access to new global markets. Examples include:

- The Port of Vancouver Authority initiated construction of the Deltaport truck staging facility in 2017, expected to be completed in 2018. The project will improve road safety, reduce port-destined truck queues and result in less engine idling and traffic congestion around the Deltaport marine terminal.

- In August 2017, the Port of Trois-Rivières inaugurated Terminal 13, a two-berth multi-purpose terminal for dry and liquid bulk. The terminal includes a large outdoor storage area as well as rail and road links.

- In September 2017, the Montréal Port Authority completed the revitalization of its Alexandra Pier and cruise terminal. The project will allow the port to accommodate an increasing number of passengers from marine tourism on the St. Lawrence River.

The private sector also continues to invest in CPAs through privately-funded infrastructure projects, such as the $50-million G3 Canada Ltd. grain terminal at the Port of Hamilton that opened on June 2017.

In 2017, DP World completed the expansion of the Fairview Container terminal at the port of Prince Rupert, which increases annual throughput capacity by 60%, from 850,000 to 1.35M Twenty-Foot-Equivalent Units (TEU). The terminal can now accommodate the largest container vessels in the world.

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System

In 2017, the agreement between the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation and Transport Canada to manage, maintain and operate the St. Lawrence Seaway was extended to March 31, 2023. See the section on Canada’s Transportation System, for more details on the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System.

Industry Structure

International

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 80% of the world’s trade travels by sea. This represented 10.3 billion tonnes in 2016. According to UNCTAD’s Maritime Transport 2017, the world’s seaborne trade volumes increased by 2.6% in 2016, up from 1.8% in 2015. This is still below the historical average of 3% recorded in the past 40 years.

A number of structural changes in the maritime world have impacted business models and merchandise flows both at home and abroad.

For example, the international marine industry is actively pursuing the implementation of new technologies, such as autonomous ships and blockchain, with the goal of creating efficiencies and enabling growth.

Overcapacity in recent years has also triggered a series of new mega alliances between container carriers. Vessel sharing agreements are not new, but three mega alliances now control almost 90% of container capacity on major trade lanes.

In June 2016, the expanded Panama Canal began commercial services, doubling its capacity. The Canal, which can now accommodate Post-Panamax vessels of up to 13,000–14,000 TEUs, has diverted some flows of international traffic from the North American West Coast to the East and Gulf Coasts, as well as causing vessel deployment patterns to shift. The increasing use of larger vessels in the global fleet requires ports to have sufficient capacity to service them. This in turn, requires matching surface connection capacity to ensure the efficient flow of goods along the supply chains.

In an effort to further improve our relationship with key trading partners and enhance the attractiveness of Canada as a gateway to the North American market, the Canada-European Union (EU) Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement introduced new market access for EU entities to the domestic marine sector. Effective September 21, 2017, eligible EU and Canadian entities can engage in the following activities without a coasting trade licence:

- the repositioning of their owned or leased empty containers on a non-revenue basis;

- providing feeder services for exported or imported goods between the Ports of Halifax and Montréal;

- privately procured dredging service contracts using vessels of any registry; and,

- provisions allowing EU enterprises using EU- registered vessels to bid for federal dredging project contracts above the Agreement’s procurement threshold of 5 million Special Drawing Rights (i.e., CDN$8.5 million) while still requiring a coasting trade licence. However, the licencing requirement that a “suitable Canadian registered and duty-paid vessel not be available” will not apply.

Domestic

Canadian registered vessels are active in domestic commercial activities, carrying on average 98% of domestic tonnage, as well as in trade between Canada and the U.S. In contrast, Canadian shippers rely predominantly on foreign registered fleets to carry goods to non U.S. international destinations.

The domestic marine sector’s main activity is the transportation of bulk cargo. This sector is also critical for northern resupply and offshore resource development. There are also a number of passenger services across Canada.

Ferries in Canada provide an important transportation link for coastal and island communities, as well as communities separated by river or lake crossings where crossing demands do not warrant building a bridge. Ferries also play a vital role in resupplying some communities across the country. The members of the Canadian Ferry Association, which includes all major ferry routes in Canada, carried more than 55 million passengers and more than 19 million vehicles in 2015.

The Canadian Commercial Fleet

In 2017, Canada’s commercial registered fleet (1,000 gross tonnage and over) had 189 vessels with a total of 2.3 million gross tonnesFootnote 2. The dry bulk carriers formed the fleet’s backbone, with 50% of the gross tonnage and 30% of vessels, followed by tankers and general cargo vessels.

There was also a large active fleet of 510 tugs and 2,031 barges (15 gross tonnage and over) operating in Canada, mainly on the Pacific coast.

Safe And Secure Transportation

In 2016, the Prime Minister launched a $1.5 billion national Oceans Protection Plan (OPP) to support responsible shipping; restore and preserve marine ecosystems; strengthen partnerships with Indigenous and coastal communities; and, invest in evidence-based emergency preparedness and response to protect Canadians and our coasts.

As part of the OPP, the Government of Canada also announced other initiatives, including:

- funding in science to help mitigate and prevent marine incidents;

- the opening of the first of seven new search rescue lifeboat stations in Newfoundland and Labrador; and,

- an inshore Rescue Boat Station in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut for search and rescue capabilities.

As part of the OPP, the Government of Canada launched a national Strategy to Address Abandoned and Wrecked Vessels. The Strategy includes the implementation of measures to address the impacts and risks posed by abandoned, dilapidated and wrecked vessels, including measures related to education and awareness, research on boat recycling, legislative changes, enhancements to vessel owner identification systems, development of an inventory of vessels and risk ranking methodology, and both short and long term funding that will help remove abandoned and wrecked vessels from the water.

Under this Strategy, Bill C-64, the Wrecked, Abandoned and Hazardous Vessels Act (WAHVA), was introduced in Parliament in October 2017. This proposed legislation aims to protect coastal and shoreline communities, the environment and infrastructure by implementing the Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks, 2007, and by holding vessel owners responsible for their vessel throughout its life-cycle, including its disposal.

As a core member of the Marine Security Operations Centres, Transport Canada continues to partner with other federal government departments and agencies to leverage our combined capability, capacity and authority to enhance Canada’s marine security.

Green And Innovative Transportation

In 2013, Canada adopted a number of measures developed at the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to reduce air pollutant and GHG emissions from ships.

Since January 1, 2015, under the North American Emission Control Area in coastal waters, vessels operating in Canada must use fuel with a maximum sulphur content of 0.1% or use technology that results in equivalent sulphur emissions, to reduce air pollutants. In the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System, progress continued under the Fleet Averaging Regulatory Regime to reduce sulphur emissions from domestic vessels. It is expected that these measures will reduce sulphur oxide emissions from vessels by up to 96% by 2020.

The Energy Efficiency Design Index requires newly-built vessels engaged in international maritime transport to meet progressively stricter minimum energy efficiency standards from January 1, 2015 onwards. The Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan requires all ships to monitor their energy efficiency.

To protect Canadian waters from invasive species, Transport Canada:

- requires ships to manage their ballast water; and,

- conducts joint inspections with U.S. authorities to verify that all vessels from overseas entering the Seaway meet ballast water regulations.

In 2010, Canada acceded to the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments, 2004, requiring ships to manage their ballast water. On September 8th, 2017 more than sixty countries, including Canada, welcomed its entry into force. Moving forward, Transport Canada will be amending its Ballast Water Control and Management Regulations to fully bring the Convention into force in Canada and will continue to work closely with the U.S. towards compatible, practicable and environmentally protective ballast water requirements on the Great Lakes.

A world-leading marine safety system requires strong environmental protection for Canada’s coastal habitants, ecosystems and marine species, including whales.

Through the OPP, the Government of Canada is committed to preserving and restoring coastal marine ecosystems that are vulnerable to increased marine shipping marine shipping, while reducing the impact of day-to-day vessel traffic on endangered whales, including from the effects of underwater vessel noise and vessel. Through the OPP, the Government of Canada is committed to preserving and restoring coastal marine ecosystems that are vulnerable to increased strikes. The Government of Canada is working on this in collaboration with many partners, including the shipping industry, academia, Indigenous groups and environmental organizations.

Recent actions in regards to underwater noise include:

- Supporting a Green Marine study on anthropogenic sources of noise, and the development of a performance measurement target for noise within the Green Marine program;

- Supporting a noise metrics workshop in collaboration with the Coastal Oceans Research Institute to identify how to best quantify noise relative to the Southern resident killer whale;

- Undertaking a Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat process to evaluate the feasibility of options to mitigate noise;

- Hosting a Southern Resident Killer Whale Symposium to bring together Indigenous groups, other governments and stakeholders to discuss how we can work together collectively to address threats to these whales in a more integrated and effective manner;

- Launching a formal risk assessment process of key noise mitigation options; and working to bring attention to this issue at the IMO.

In response to the 12 North Atlantic right whale deaths during the summer of 2017, some of which were determined to be as a result of ship strikes, Transport Canada temporarily implemented a speed restriction (August to January) for vessels 20 metres or more to a maximum of 10 knots in the western Gulf of St. Lawrence. The Government of Canada continues to work closely with all relevant stakeholders on approaches to reducing the risk of vessel strikes in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to help protect the North Atlantic Right Whale.

Highlight: Oceans Protection Plan

As part of the OPP, the Government has announced initiatives worth more than $1.5 billion, including:

- Building Meaningfull Partnerships

Coordination of a national approach for engagement and building regional Indigenous partnerships.

- Whales - Marine Mammals

Completion of three science reviews of recovery actions, organization of engagement sessions, a Symposium on Southern Resident Killer Whales, a Minister's roundtable on the North Atlantic Right Whale and, imposition of slowdowns zones in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

- Cumulative Environmental Impacts

Identification of six pilot sites to collect environmental data and improve understanding of cumulative effects to protect sensitive habitat and species.

- Pilotage Act Review

Finalization of the final report following completion of roundtables.

- Engaging Canadians

Creation of the Let's Talk OPP Portal to consult Canadians on OPP initiatives.

- Vessels of Concern

Implementation of a National strategy on abandoned and wrecked vessels: introduction of new legislation (Bill C-64), creation of the Abandoned Boats Program and the Abandoned and Wrecked Vessel Removal Program, engagement on improvements to vessel owner identification systems and on the creation of owner-financed remediation funds, development of a national inventory and risk ranking methodology.

Chapter 5 Rail Transportation Sector

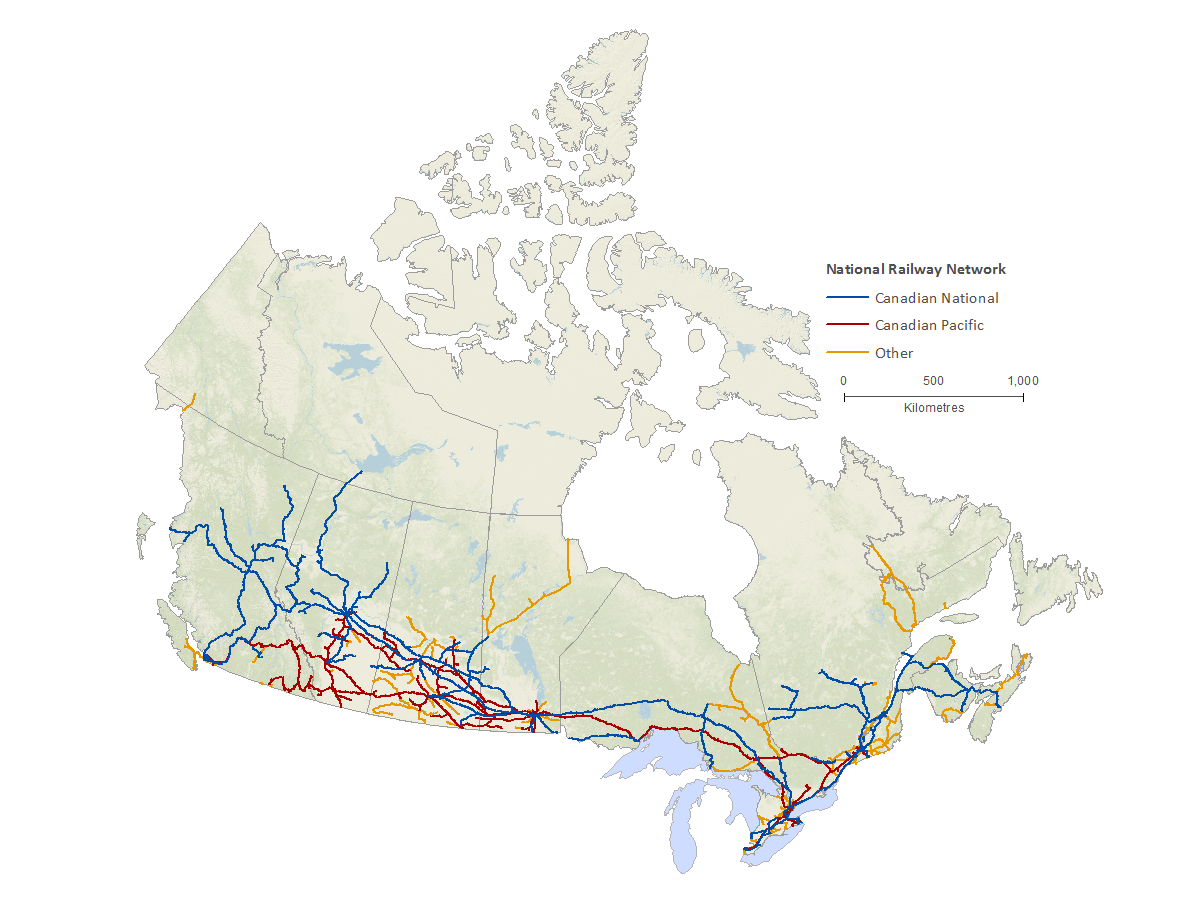

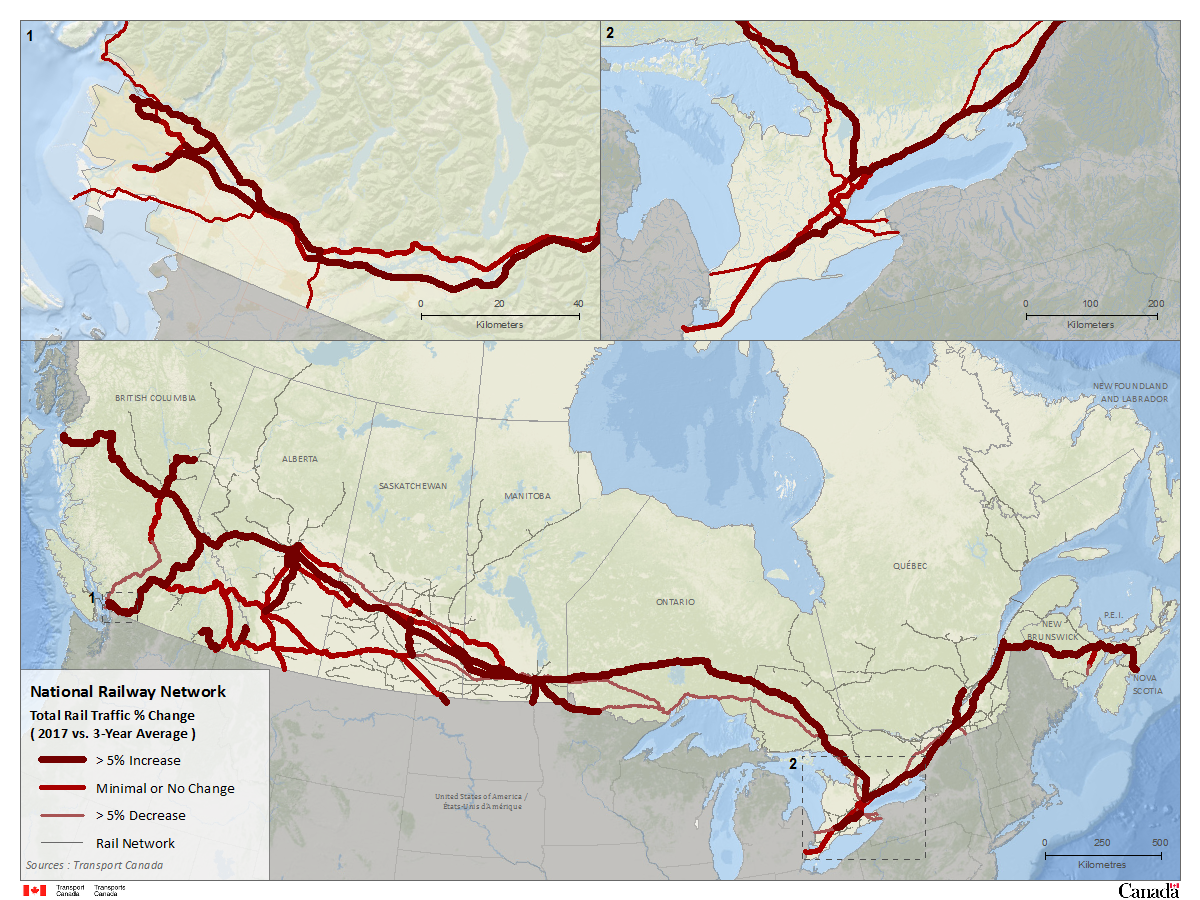

Image Description - Map: Rail Transportation Network

The map of Canada shows the layout and extent of the Canadian rail system. This system currently has over 45,000 route-kilometres of track broken down into Canadian National track (52.2 per cent of the system, represented by blue lines), Canadian Pacific track (30.8 per cent, represented by red lines) and other railways track (17.0 per cent, represented by orange lines).

Highlights

- The recently passed Transportation Modernization Act will improve rail system efficiency, safety, competition and transparency

- The Minister of Transport launched the Statutory Review of the Railway Safety Act a year ahead of schedule

- The Locomotive Emissions Regulations, which came into force in June 2017, will limit harmful emissions through mandatory emission standards and reduced idling

- Transport Canada announced funding under the Rail Safety Improvement Program to support improvement on the rail network, the use of technologies, as well as research

Industry Infrastructure

The Canadian rail system currently has 41,711 route- kilometers (km) of track, as illustrated on Map 7 in Annex A:

- Canadian National (CN) owns 52.2% (21,782 km);

- Canadian Pacific (CP) owns 30.8% (12,856 km); and,

- Other railways own 17.0% (7,073 km).

The rail system also includes:

- 19 intermodal terminals operated by either CN or CP to run truck/rail and container intermodal services;

- 27 rail border crossings with the U.S.; and,

- Multi-modal inland ports, such as CentrePort Canada in Manitoba and Global Transportation Hub Authority in Saskatchewan.

Industry Structure

The freight rail transportation sector specializes in moving heavy bulk commodities and containerized traffic over long distances.

The passenger rail sector provides commuter, intercity and tourist transportation services.

The Canadian rail system is operated by over 60 rail companies, 26 of them being federally-regulated companies holding a valid Certificate of Fitness from the CTA.

Canada has two major Class I freight railways, CN and CP, responsible for most freight rail traffic.

VIA Rail, a Crown corporation established in 1977, operates Canada’s national passenger rail service on behalf of the Government of Canada.

VIA Rail operates intercity services in the Québec- Windsor corridor, long-distance services across Canada and regional services that provide mobility to rural communities. VIA Rail operates mainly over CN and CP tracks. VIA Rail’s proposal for high-frequency rail includes sections of dedicated tracks and has the potential to provide Canadian travellers with better service by reducing trip times, improving reliability and enhancing flexibility. Budget 2018 has provided funding to continue an in-depth assessment of this proposal.

Budget 2018 announced funding to acquire 32 bi- directional train sets to replace the current rolling stock operating within the Québec City- Windsor corridor. The new fleet will provide continued safe and reliable passenger rail services, reduced environmental impacts, improved traveller experience, and accessibility for people with reduced mobility.

Amtrak, an American passenger railroad, provides two cross-border passenger rail services to Montréal and Vancouver and a joint cross-border service to Toronto with VIA Rail.

Some large U.S.-based carriers have freight rail operations in Canada. Examples include the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railway Company and CSX Transportation Inc.

CN, CP, and BNSF provide strategic links in the trade route between Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. BNSF’s service to Canada’s Pacific Gateway gives Vancouver the unique advantage of being the only port on the North American West Coast served by three Class I railroads.

Canada is also serviced by more than 50 short line railways, some of which are federally regulated while others are provincially regulated. Short lines typically connect shippers to Class I railways, to other short lines or to ports to move products across longer distances. Short lines are collectively responsible for transporting $20.3 billion worth of freight to and from continental rail networks, such as CN and CP, and to ports and terminals. In addition to short lines focused on moving freight, there are also short lines that focus on providing tourist rail services, such as the Rocky Mountaineer Railway.

In terms of equipment, Class I railway carriers had 2,766 locomotives in 2016, and 52,060 freight cars, mainly hopper cars, boxcars, flatcars and gondolas.

In May 2017, following extensive consultation with stakeholders, the government tabled Bill C-49, the Transportation Modernization Act, in Parliament. It received Royal Assent in May 2018. This legislation will support a transparent, fair, efficient, and safe Canadian freight rail system that meets the long-term needs of users and facilitates trade and economic growth.

Bill C-49’s freight rail amendments aim to address emerging pressures in the system, to ensure it meets the need of users and the economy over the long-term. This includes a new and improved suite of measures, including more timely and effective shipper remedies with the Canadian Transportation Agency, as well as new data provisions that would greatly improve the transparency of the supply chain and help proactively identify and address transportation challenges in the future.

Beginning in the fall of 2017, a harsh winter combined with strong demand for rail services exposed temporary capacity issues with parts of Canada’s freight rail system. In response to this highly publicized event, in March 2018 the Minister of Transport took measures to ensure the public reporting of recovery and future investment plans for the information of all members of the affected supply chains. The passage of Bill C-49 and the implementation of the Canadian Centre on Transportation Data, among other measures, will ensure that similar transparency is standard in the future.

Safe And Secure Transportation

On April 26, 2017, the Minister of Transport launched the Statutory Review of the Railway Safety Act, a year ahead of schedule. The Review focuses on the effectiveness of the federal rail safety legislative and regulatory framework, the operations of the Act itself, and the degree to which the Act meets its core objective of ensuring that rail safety is in the best interest of Canadians. The Report was tabled on May 31, 2018.

Bill C-49 will require the mandatory installation of locomotive voice and video recorders in locomotive cabs while protecting the privacy of railway employees.

On June 16, 2017, the Prevention and Control of Fires on Line Works Regulations came into force, which set out the planning and prevention measures required by railway companies to reduce the likelihood of fires caused by railway operations.

On November 11, 2017, a Notice of Intent was published in the Canada Gazette, Part 1, to outline a proposed approach to incorporate up-to-date fatigue science in current requirements and further strengthen Canada’s rail safety regime.

In 2017, the Minister of Transport announced more than $20 million of funding under the Rail Safety Improvement Program. Funding was used to support 131 projects covering safety improvements on rail crossings and along rail lines, the use of innovative technologies, research to improve rail safety, closures of grade crossings and public education and awareness initiatives.

In addition, Transport Canada continued applying regulations that had previously came into force, such as the:

- Administrative Monetary Penalties Regulations;

- Railway Operating Certificate Regulations;

- Grade Crossings Regulations;

- Railway Safety Management System Regulations, 2015; and,

- Amendments to the Transportation Information Regulations.

Freight trains transporting dangerous goods can be particularly vulnerable to misuse or sabotage, given the harmful nature of the goods and the extensive and accessible nature of the railway system. To mitigate these risks and to demonstrate the Government of Canada’s commitment to safe communities and better aligning Canadian standards with international standards, Transport Canada is proposing the introduction of risk-based security regulations for the transportation of dangerous goods by rail in Canada. The proposed Transportation of Dangerous Goods by Rail Security Regulations were pre-published in Canada Gazette Part I in June 2017. The section on Transportation of Dangerous Goods provides more information on the different initiatives related to dangerous goods.

In response to recent terrorist attacks in various countries, such as the Saint Petersburg metro bombing in April 2017, among others, Transport Canada continues to conduct security inspections at freight and passenger rail sites across Canada. In 2017, Transport Canada continued to engage with key stakeholders through various means, including regional multimodal classified security briefings and the annual Canadian Surface Transportation Security Roundtable. These initiatives promote information sharing and the discussion of best practices, in order to improve the security of Canada’s transportation system.

Transport Canada continues to carry out ongoing oversights and enforcements of the rail safety legislative and regulatory regime.

Green And Innovative Transportation

Transport Canada has been working with the rail industry to address GHG emissions through voluntary work under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Railway Association of Canada.

The current MOU has been in place since 2011 and was extended to the end of 2017. The latest annual report published under the MOU shows the GHG emission intensity from rail freight operations in 2015 increased slightly by less than 1% compared to 2014. The emissions from intensity from intercity passenger operations did not substantially change. However commuter operation emissions intensity increased by 13%, attributed to increased service levels.

To support the research of new and emerging clean technologies with application to the rail industry, ten grants of $25,000 each were awarded to academic research programs in 2017. Example areas of study in 2017 were advancements in alternative energy sources, light weighting material, and electrical energy storage.

On June 9, 2017, the Locomotive Emissions Regulations entered into force. The Regulations will limit harmful emissions from locomotives operated by railway companies under federal jurisdiction through mandatory emission standards and reduced idling. These regulations align with those of the U. S., which was one of the goals of the Canada-U.S. Regulatory Cooperation Council Locomotive Emissions Initiative.

Chapter 6 Road Transportation Sector

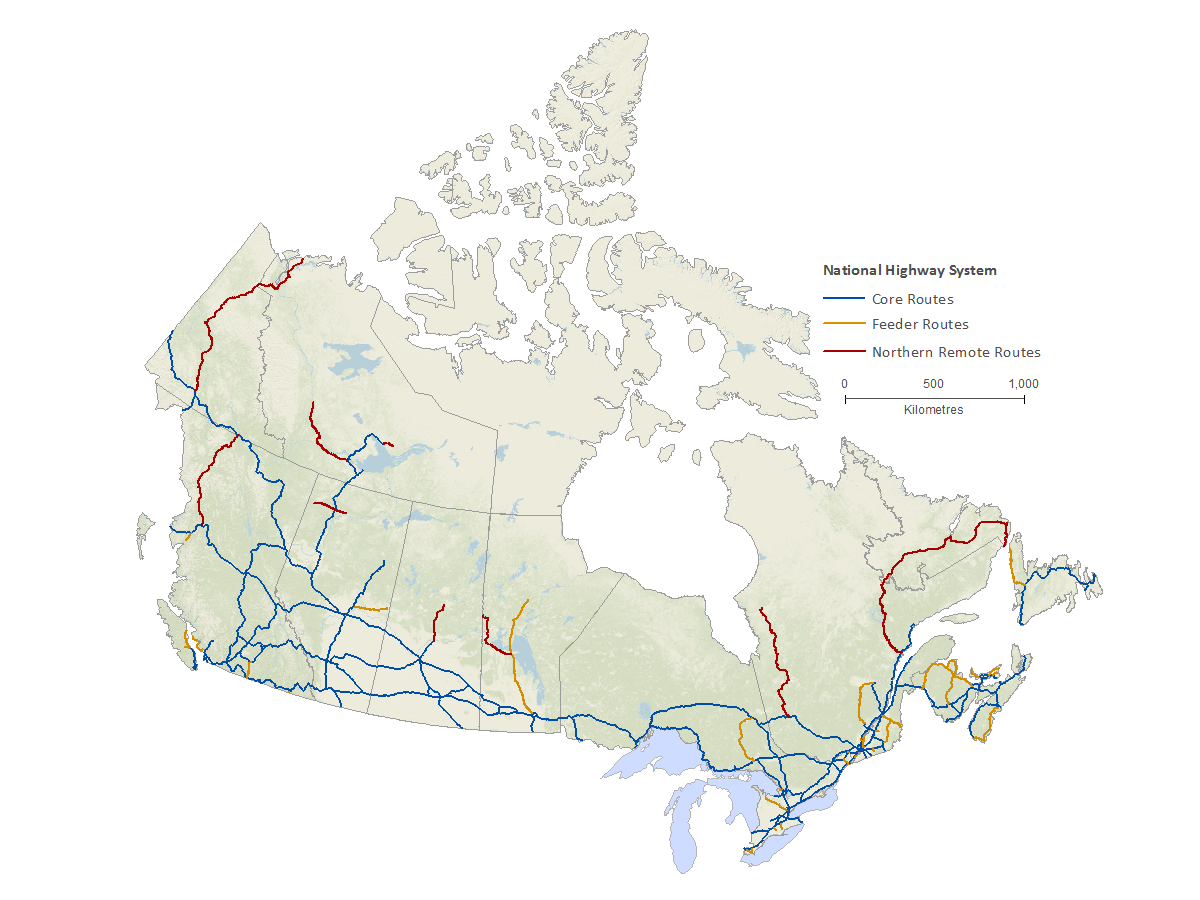

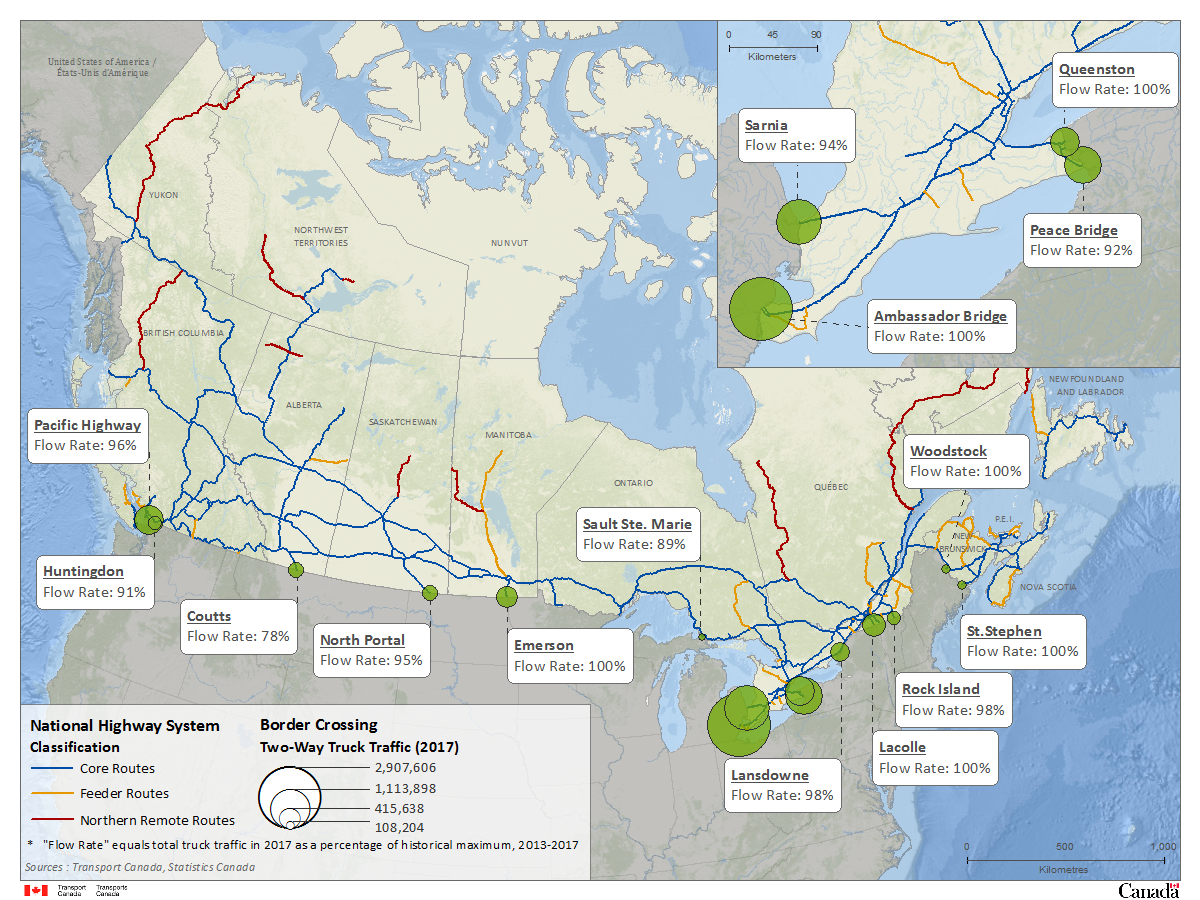

Image Description - Map: Road Transportation Network

The map of Canada shows the location of the NHS. The NHS includes over 38,000 kilometers of Canada’s most important highways from coast to coast. Core routes (which represent 72.9 per cent of the NHS) are illustrated by blue lines, Feeder routes (which represent 11.6% of the NHS) by orange lines and Northern and Remote routes (which represent 15.5 per cent of the NHS) by red lines.

Highlights

- Bill S-2, an amendment to the Motor Vehicle Safety Act, will enhance defect and recall powers, provide an administrative monetary penalty system and provide some flexibilities for introducing new technologies

- Transport Canada launched the Program to Advance Connectivity and Automation in the Transportation System to help Canadian jurisdictions prepare for the introduction of connected and automated vehicles

- The Government of Canada continues to work with provinces and territories on the development of a Canada-wide strategy for Zero Emission Vehicles

Industry Infrastructure

Most passengers and goods in Canada travel by road. In 2016, more than 24.2 million road motor vehicles were registered in Canada, up 1.45% from 2015. 92.3% were vehicles weighing less than 4,500 kilograms, mainly passenger automobiles, pickups, Sport Utility Vehicles (SUV) and minivans. 4.3% were medium and heavy trucks weighing 4,500 kilograms or more, and 3.3% were other vehicles such as buses, motorcycles and mopeds.

There are more than 1.13 million two-lane equivalent lane-kilometres of public road in Canada.Footnote 1 Approximately 40% of the road network is paved, while 60% is unpaved. Four provinces — Ontario, Québec, Saskatchewan, and Alberta — account for over 75% of the total road length.

In 2016, the National Highway System (NHS) included over 38,049 lane-kilometres:Footnote 2

- 72.9% were classified as Core routes;

- 11.6% were classified as Feeder routes; and,

- 15.5% were classified as Northern and Remote routes.

As shown on Map 8 in Annex A, the NHS consists mainly of interprovincial and international road linkages.

All travel on the NHS increased 12% from 2005 to 2015. Truck travel on the Northern/Remote Network increased 72% from 2005 to 2015.

Industry Structure

As of December 2017, there were 69,411 businesses whose primary activity was trucking transportation. Trucking includes many small for-hire carriers and owner-operators, and some medium and large for-hire companies that operate fleets of trucks and offer logistic services. Trucking companies were concentrated in four provinces: Ontario (41.9%), Alberta (16.4%), Québec (14.6%), and British Columbia (14.3%).

The trucking industry is involved in three main types of trucking activities.

- For-hire trucking services, which fall into two main categories:

- less-than truckload, meaning the transportation of relatively small-sized freight from different shippers in a truck; and,

- truckload, meaning the transportation of a shipment from a single shipper in a truck.

- Courier operators, which specialize in transporting parcels. As of December 2017, there were 12,033 companies with courier or messenger services as their main line of business.

- Private carriers, where businesses maintain a fleet of trucks and trailers to carry their own goods, such as Walmart and Costco. While the Government of Canada has not tracked this component of trucking in the past as it was not the primary activity of such non-transportation companies, investment is being made to track this activity in the future as part of the new Canadian Centre on Transportation Data.

Trucking companies can also be classified as intraprovincial or extraprovincial, meaning ones that routinely cross provincial or international boundaries.

At the September 2016 meeting of the Council of Ministers Responsible for Transportation and Highway Safety, the Ministers agreed to form a new federal/ provincial/territorial task force to study interprovincial truck-related regulations and improve the efficiency of interprovincial trucking wherever possible. The Task Force was formed in January 2017 with a final report expected by fall 2019.

In December 2016, Canadian Tire unveiled 53 and 60-foot prototype intermodal trailers for use on Canadian highways, and were successfully tested on CP’s network. In 2017, Ontario continued to examine the use of 60’ semitrailers, as compared to conventional 53’ semitrailers, via the Extended Semitrailer Trial, which was expanded beyond the retail sector. British Columbia is also working with Canadian Tire on piloting the operation of 60’ container trailers.

Safe And Secure Transportation

In 2018, Bill S-2, an amendment to the Motor Vehicle Safety Act, will soon become law. It will:

- enhance defect and recall powers;

- provide an administrative monetary penalty system; and,

- provide some flexibilities for introducing new technologies.

Green And Innovative Transportation

Throughout 2017, the Government of Canada worked with provinces and territories on the development of a Canada-wide strategy for zero emission vehicles (ZEVs). An Advisory Group and a number of experts from industry, non-governmental organizations, academia and other stakeholders were engaged to conduct detailed analyses of challenges and opportunities. They provided advice on topics related to vehicle supply, charging and refueling infrastructure readiness, costs and benefits of ownership, public awareness and education, and clean growth and jobs.

The Government of Canada has already taken steps to support ZEVs by investing over $180 million in charging stations and other alternative refueling infrastructure. Federal, provincial and territorial Ministers of Transport agreed to finalize a strategy in 2018. The Government of Canada continued its work to develop emissions standards for post- 2018 model year on-road heavy-duty vehicles and engines, building on the existing regulations covering model years 2014 to 2018. On March 4, 2017, the Government of Canada published proposed amendments to the existing Heavy-duty Vehicle and Engine Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations.

These proposed amendments would:

- establish progressively stricter standards to further limit GHG emissions from new on-road heavy-duty vehicles and their engines of the 2021 and later model years; and,

- introduce new standards for new trailers hauled by on-road transport tractors in Canada beginning in the 2018 model year.

The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change includes a commitment for the federal government to work with provinces, territories and industry to develop new requirements for heavy-duty trucks to install fuel-saving devices like aerodynamic add-ons. The work was initiated in 2017.

With funding received under Trade and Transportation Corridor Initiative, in 2017, Transport Canada launched the Program to Advance Connectivity and Automation in the Transportation System. The program aims to help Canadian jurisdictions prepare for the array of technical, regulatory and policy issues that will emerge as a result of the introduction of connected and automated vehicles.

Chapter 7 Transportation of Dangerous Goods

Highlights

- In 2017, Transport Canada continued to strengthen oversight of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods, having close to 90 inspectors, resulting in approximately 5200 inspections and 154 enforcement actions during the year. Training for inspectors and their supporting employees has also increased.

- Completion of additional phases of the Jack Rabbitt II project to address rapid large- scale release of Toxic Inhalation Hazard gases from railcars

- In 2017, progress was made on the regulatory review and amendments to several parts of the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations to enhance current regulations for increased compliance, and improvement in the public safety of Canadians

Safety in the transportation of dangerous goods continues to be strengthened across the country through the following measures and initiatives that Transport Canada has undertaken:

Increasing Resources and Capabilities in Inspection Regime