This document presents the TERMPOL Review Report of the co-venture project led by Chevron Canada Ltd and Woodside Energy (Canada) International Ltd. Their proposition is to build and operate a liquified natural gas (LNG) facility and marine terminal to store and export LNG within the District of Kitimat, British Colombia. The report summarizes the outcome from the Technical Review of the proponent’s submissions of surveys and studies with regard to the marine transportation components of the proposed project.

On this page

- Glossary

- Acronyms

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Analysis

- Indigenous engagement

- Conclusion

- Appendices

Forward

This report was prepared and approved by the following government authorities:

- Transport Canada

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada (including Canadian Hydrographic Service)

- Canadian Coast Guard

- B.C. Coast Pilots

- Pacific Pilotage Authority

Glossary

Aids to Navigation: External devices or systems that help mariners determine position and course. The aids warn of dangers or obstructions and often indicate the preferred route through a given waterway. The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) is responsible for delivering operational aspects of navigation programs and services, including aids to navigation.

Automated Identification System (AIS): Vessels of 300 gross tonnes or more (other than fishing vessels) engaged on an international voyage and domestic vessels of 500 tonnes gross tonnage or more (other than fishing vessels) must be fitted with AIS. AIS automatically provides information, including the vessel identity, type, position, course, speed, navigational status and other safety-related information, to AIS-equipped shore stations, satellites, other vessels and aircraft. These vessels can automatically receive information from other similarly fitted vessels, as well. This improves a vessel’s situational awareness and the ability of shore VTS to identify and monitor marine traffic. All CCG Marine Communication Traffic Services (MCTS) centres regulating vessel traffic are equipped with AIS infrastructure.

Ballast Water: Water on board a vessel to increase the draught and change the trim of the vessel to regulate stability or maintain stress loads within acceptable limits.

Ballast Water Control and Management Regulations: Under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, the regulations apply to the management of ballast water on all ships entering waters under Canadian jurisdiction from beyond the Canadian exclusive economic zone.

Canada Marine Act: The principal legislation governing federal ports in Canada, including Canada Port Authorities and public ports. The Canada Marine Act includes federal ports’ authorities to maintain safe navigation and environmental protection within port boundaries, including directing and controlling vessel traffic.

Canada Shipping Act, 2001 (CSA, 2001): The CSA, 2001 is one of the principal laws that govern safety in marine transportation (including the protection of the marine environment). The CSA, 2001:

- Seeks to balance shipping safety and marine environment protection while encouraging maritime commerce

- Applies to all vessels operating in Canadian waters and Canadian vessels worldwide and in some cases, to foreign vessels up to the Exclusive Economic Zone

Canadian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ): The CanadianExclusive Economic Zone is an area of sea beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea of Canada, which extends to 200 nautical miles from the nearest point of the baselines. Within the EEZ, Canada has sovereign and jurisdictional rights for the purposes of exploration and economic exploitation. Canada has jurisdiction for conserving and managing the natural resources of the waters, seabed and subsoil.

Classification Societies: To help ensure vessel safety,organizations such as Lloyd’s Register, the American Bureau of Shipping, and Det Norske Veritas certify that vessels are built, maintained and operated according to established and recognized rules, regulations and standards.

Collision Regulations: The Collision Regulations (CRC, c1416), which are created under CSA, 2001, set out the rules that vessels must follow to prevent collisions while in Canadian waters. These rules are based on the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREG).The COLREGs provide uniform measures in regard to the safe conduct of vessels. The regulations describe rules of general conduct specific to the:

- Navigational, steering and sailing rules

- Navigational lights and shapes to be displayed

- Sound and light signals to be used by every vessel and pleasure craft in Canadian waters

Escort Tug: A ship capable of assisting or towing larger vessels. The scope and range of assistance capabilities can vary depending on the size and type of vessels tugs accompany. Some escort tugs can be tethered to the vessel to provide a different level of service.

Fisheries Act: The principal legislation that protects the sustainability and productivity of recreational, commercial and Indigenous fisheries. The Act and, more specifically, its fisheries protection provisions, establish authorities for the protection of recreational, commercial, and Indigenous fisheries. These authorities include the prohibition against carrying out projects that result in serious harm to fish and the powers related to fish passage and flow.

Flag State: Country of registry of a vessel, often a seagoing one. The Flag State sets the safety standards and pollution prevention requirements that apply to vessels flying its flag.

International Code for Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquid Gases in Bulk (IGC Code): The code for the construction and equipment of ships carrying liquefied gases in bulk. This code has been developed to provide an international standard for the safe carriage of liquefied gases by prescribing the design and constructional features of ships, and the equipment they should carry as to minimize the risk to the ship, its crew, and the environment.

International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments (BWM): Adopted in 2004, this Convention aims to prevent the spread of harmful aquatic organisms from one region to another by:

- Establishing standards and procedures for managing and controlling ships' ballast water and sediments

- Requiring all ships in international traffic to manage ballast water and sediments to a certain standard, according to ship-specific ballast water management plans

- Requiring all ships to carry a ballast water record book and an international ballast water management certificate

International Convention on Liability and Compensation for Damage in Connection with the Carriage of Hazardous and Noxious Substances by Sea (HNS Convention): The International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted the International Convention on Liability and Compensation for Damage in connection with the Carriage of Hazardous and Noxious Substances by Sea (2010 HNS Convention) in April 2010. This Convention is based on the model for pollution damage caused by spills of persistent oil from tankers. Once in force, it will have a two-tiered system for compensation to claimants in the event of a ship-source accident at sea involving HNS.

International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL): In Canada, discharges are governed under the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations. These regulations implement requirements of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), known as the MARPOL Convention. MARPOL is the primary international Convention aimed at preventing pollution of the marine environment by ships from operational or accidental causes.

International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation (OPRC Convention): Adopted in 1990, the OPRC Convention aims to provide a global framework for international co-operation in combating major incidents or threats of marine pollution. Parties to this Convention, including Canada, must establish measures for dealing with pollution incidents, either nationally or in co-operation with other countries.

International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW): This Convention sets minimum standards for the training, certification and watchkeeping of vessel crews that countries must meet or exceed.

International Maritime Organization (IMO): Established in 1948, the IMO provides a forum for countries to negotiate their government’s approved positions on international standards for the safety, security and environmental performance of international shipping. The IMO's primary role is to develop and maintain a comprehensive regulatory framework for shipping. The IMO scope includes safety, environmental concerns, legal matters, technical cooperation, maritime security and the efficiency of shipping. Canada is one of 171 IMO member countries. When agreement is reached at the IMO, member countries (like Canada) then create regulatory domestic frameworks for the shipping industry. There are over 50 IMO conventions covering a range of topics. The conventions are reflected in Canada’s marine safety and security system, including in the CSA, 2001. Canadian maritime laws apply to all vessels operating in Canadian waters and Canadian vessels worldwide.

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG): LNG is natural gas in liquid state. When natural gas is chilled to approximately minus 160° Celsius (minus 260° Fahrenheit) at atmospheric pressure, it becomes a clear, colourless, and odourless liquid. LNG is non-corrosive, non-toxic and cryogenic, and is classified as a hazardous and noxious substance by the IMO. LNG is converted back to natural gas after its arrival to the destination.Footnote 1 In liquid form, LNG is approximately 1/600th the volume of natural gas, which allows for efficient transport in purpose-built ocean carriers.

Marine Communications and Traffic Services (MCTS): The MCTS program provides safety radio-communication and commercial marine telephone services, and vessel traffic information on a 24/7 basis. Management and operation of the MCTS is under the purview of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans under Part 5 of the CSA, 2001. The CCG is the operational authority for the MCTS.

Marine Liability Act (MLA): In force since August 2001, the MLA is the principal law dealing with shipowner and vessel operator liability for passengers, cargo, pollution and property damage. The Act sets limits of liability and establishes uniformity by balancing the interests of shipowners and other parties. The MLA gives many IMO Conventions the force of law.

Oil Companies International Marine Forum (OCIMF): The OCIMF is a voluntary association of oil companies that promote the safe design and operation of tankers and terminal operations related to crude oil, oil products, petrochemicals and gas. Formed in 1970 in response to growing public scrutiny of marine pollution, the association aims to be the authority on the safe and environmentally-responsible operation of oil tankers and terminals. The current membership includes every major oil company in the world along with the majority of national oil companies. The association regularly represents the views of industry at the IMO and has become an advocate for marine safety standards and regulations.

Protocol on Preparedness, Response and Co-operation to Pollution Incidents by Hazardous and Noxious Substances (OPRC–HNS Protocol): Established in 2000 by the IMO as an addition to the OPRC Convention, the OPRC-HNS Protocol follows similar principles. The intent is to make ships carrying HNS and HNS-handling facilities subject to a preparedness and response program similar to what is in place for oil incidents.

Pacific Pilotage Regulations: Rules under the Pilotage Act for the operation, maintenance and administration of pilotage services in B.C. The regulations establish compulsory pilotage areas and describe minimum qualifications for holding licences and pilotage certificates within the Pacific Pilotage Authority’s (PPA) region.

Paris Memorandum of Understanding (MOU): Aims to eliminate the operation of substandard ships through a harmonized system of Port State Control. Port State Control ensures vessels meet international safety, security and environmental standards, and that crew members have adequate living and working conditions. The agreement consists of 27 participating maritime administrations, including Canada, and covers the waters of the European coastal states and the North Atlantic basin from North America to Europe.

Place of Refuge: Marine location where a ship in need of assistance can take action to conduct repairs, reduce hazards to navigation, and protect human life and the environment.

Pilotage: The rules requiring vessels operating within specified waters to be under the conduct of a licensed Canadian marine pilot with local knowledge of the waterway to help guide the vessel safely to its destination.

Pilotage Act: Enacted in 1972 and amended in 1998, the Act establishes Pilotage Authorities in four regions across Canada, including the Atlantic, the Laurentian, the Great Lakes and the Pacific. The Pilotage Authorities establish compulsory pilotage areas. In these areas, vessels of certain types, including all tankers, must take local marine pilots on board before they enter harbours or busy waterways. The local pilots must have expertise in navigation, the handling characteristics of the vessels they are guiding, as well as expertise in navigating the local waterways. They safely guide ships to port.

Port State Control: Inspection of foreign vessels in national ports to verify they meet major international conventions related to condition and equipment as well as crew and operations. Port State Control is Transport Canada’s primary means for ensuring compliance with the CSA 2001, the Marine Transportation and Security Act, and applicable international conventions that have been implemented into Canadian legislation. This is a vessel inspection program established under the IMO, whereby countries sharing common waters agree to share inspection responsibilities and information. For example, Canada is a Port State for foreign vessels that enter Canadian waters and vessels are inspected according to international agreements. In Canada, inspections determine compliance with conventions Canada has implemented.

Response Organizations and Oil Handling Facilities Regulations: These regulations are created under the CSA, 2001, and set out the rules related to the procedures, equipment and resources of response organizations and oil handling facilities during an oil pollution incident.

Ship Inspection Report Programme (SIRE): Launched in 1993 by the Oil Companies International Marine Forum to address concerns about substandard shipping, SIRE is a unique tanker risk assessment tool of value to charterers, vessel operators, terminal operators and government bodies concerned with vessel safety. SIRE includes a large database of up-to-date information about tankers and barges.

International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS): SOLAS is an international maritime safety treaty that specifies minimum standards for the construction, equipment and operation of ships, compatible with their safety. SOLAS includes the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974, and the Protocol of 1988 relating to the Convention. It is generally seen as the most important international treaty on merchant ship safety. Canada is a signatory to SOLAS.

TERMPOL “Technical Review Process of Marine Terminal Systems and Transhipment Sites”: The review originated in the 1970s when an interdepartmental committee reviewing marine pollution issues identified the need for a precise and reliable way to measure the navigational risks associated with placing and operating marine terminals for large oil tankers. The process was expanded in 1982 to include other cargos, and revised in 2001 and 2014 to reflect program and regulatory changes. TERMPOL is an extensive yet voluntary review process that a proponent who is involved in building and operating a marine terminal system for bulk handling of oil, chemicals and liquefied gases can request. It focuses on the marine transportation components of a project.

TERMPOL Review Committee (TRC): TC chairs the TRC for this Project. The following agencies and organizations have been involved in the TERMPOL Review Process: TC, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), CCG, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS), PPA and the BCCP.

Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding: Aims to eliminate the operation of substandard ships through a harmonized system of Port State Control. Port State Control ensures vessels meet international safety, security and environmental standards, and that crew members have adequate living and working conditions. The organization consists of 20 participating maritime administrations, including Canada, and covers the waters of the Asia-Pacific region.

Vessel Traffic Services (VTS): For the purpose of providing safe and efficient navigation and environmental protection, regulations have established Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) zones along Canada’s east and west coasts out to the limit of the territorial sea. VTS is a means of exchanging information between vessels and a shore-based centre. Shipping in VTS zones is monitored by the CCG’s Marine Communication Traffic Services (MCTS). Ships of 500 gross tonnes or more must report to an MCTS officer 24 hours before entering the VTS Zone and report prescribed information about the vessel and her intended route, including any pollutant cargoes and defects. Monitoring of vessel movements within a VTS Zone allows MCTS officers to provide navigational information and assistance that help on board navigational decision making.

Canada’s VTS system is operated by certified MCTS officers who monitor vessel movements using VHF (very high frequency) radio and direction-finding equipment, AIS, tracking computers and, in areas of high traffic density, surveillance radar. The CCG Western Region has two MCTS centers which operate three Vessel Traffic Services zones in B.C.; Vancouver is regulated by MCTS Victoria, and Tofino and Prince Rupert are regulated by MCTS Prince Rupert.

Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations (VPDCR): The VPDCR is created under the CSA, 2001, and sets out specific provisions for shipboard requirements and equipment to help prevent pollution from oil, noxious liquid substances, dangerous chemicals, sewage, garbage, and also include air emissions control for NOx and ozone-depleting substance.

Vessel Traffic Services Zones Regulations (VTSZR):The VTSZR is created under the CSA, 2001, and outlines communication and reporting requirements for Canadian and foreign vessels in Canadian waters. Specific requirements are in place for vessels entering Canadian waters, operating within Canadian waters or leaving Canadian waters.

VHF Radiotelephone Practices and Procedures Regulations (VHR Regulations): The VHF Regulations are created under the CSA, 2001, and set out the practices and procedures persons on board ships must follow when using bridge-to-bridge VHF radiotelephones to ensure safe navigation.

Acronyms

- AIS

- Automatic Identification Systems

- BC OGC

- B.C. Oil and Gas Commission

- CHS

- Canadian Hydrographic Service

- COLREG

- Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea

- DWT

- Deadweight Tonnage

- EEZ

- Exclusive Economic Zone

- GPS

- Global Positioning System

- HAZID

- Hazard Identification

- HNS

- Hazardous and Noxious Substance

- IMO

- International Maritime Organization

- IMDG

- International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code

- LNG

- Liquefied Natural Gas

- LNGC

- Liquefied Natural Gas Carrier

- MARCS

- Marine Accident Risk Calculation System

- MARPOL

- International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships

- MCTS

- Marine Communications and Traffic Services

- MLA

- Marine Liability Act

- MTPA

- Million Tonnes per Annum

- OCIMF

- Oil Companies International Marine Forum

- SIGTTO

- Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators

- SIRE

- Ship Inspection Report Programme

- SOLAS

- International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea

- SOPF

- Ship-Source Oil Pollution Fund

- STCW

- Standards for Training, Certification and Watchkeeping

- TERMPOL

- Technical Review Process of Marine Terminal Systems and Transshipment Sites

- TRC

- TERMPOL Review Committee

- UKC

- Underkeel Clearance

- VTS

- Vessel Traffic Services

- WCMRC

- Western Canada Marine Response Corporation

Executive summary

Project overview

As a co-venture project, Chevron Canada Ltd and Woodside Energy (Canada) International Ltd are proposing to build and operate a liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility and marine terminal to the store and export LNG within the District of Kitimat, British Columbia.

Natural gas will arrive at the Kitimat LNG terminal via a pipeline to be liquefied and loaded onto LNG Carriers ( LNGCs ) for export overseas. The development of the Kitimat LNG project will proceed in two phases (LNG trains), the first train is expected to produce 5.5 million tons per annum (MTPA), and the second train will double the volume to 11 MTPA. The resulting increase in marine traffic will amount to 150 vessel calls per year for a fully executed two-train project. The terminal berth will be designed to accommodate LNGCs ranging in size from 125,000 cubic meters (m3) to 217,000 m3 with overall lengths between 270 m and 315 m and draughts of 11 m to 12.5 m.

Purpose of TERMPOL review

In addition to fulfilling mandatory provincial and federal requirements, Chevron Canada and Woodside Energy (the proponent) have requested to have a TERMPOL Review Committee (TRC) assess the marine transportation components of their proposed Kitimat LNG Terminal Project (the project) under the voluntary Technical Review Process of Marine Terminal Systems and Transshipments Sites (TERMPOL). The membership of TRC consist of experts from federal departments and authorities with responsibilities related to safe marine transportation who review proponents’ submissions. It includes representatives from departments and agencies such as the Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard, the Pacific Pilotage Authority, and Environment and Climate Change Canada. The TERMPOL Secretariat at Transport Canada acts as the chair of the TRC.

The TERMPOL Review process aims to:

- Objectively appraise operational vessel safety, route safety and cargo transfer operations associated with a proposed marine terminal system, route or transshipment site

- Improve, where possible, those elements of a proposal which could, in certain circumstances, pose a risk to the integrity of a vessel’s hull while navigating and/or the cargo transfer operations alongside the terminal

- Critically examine the effectiveness of proponent’s plans and recommend additional potential marine safety mitigation measures where needed

TERMPOL recommendations and findings

As mandated by the TERMPOL process, in 2016, the proponent submitted a number of surveys and studies to Transport Canada (TC). The following suite of materials aims to show that:

- Kitimat LNG complies with or exceeds regulatory marine safety measures in the context of transport of hazardous materials; and

- The proponent can prevent, manage and mitigate unintentional loss of LNG containment and the associated risks with loading, navigation and natural hazards

The TRC urges the proponent to commit to implementing all 60 recommendations presented in the TERMPOL Report Appendix, including:

- LNGCs used for the Kitimat LNG project should limit their speed to a maximum of 12kn when accompanied by tug escort

- Kitimat LNG should ensure all carriers that call at the terminal possess a SIRE certificate that is no more than six months old, as part of their Carrier Acceptance Program

- Kitimat LNG should ensure that venting of boil-off gases does not occur when pilots are boarding project carriers or during pilot transfer by helicopter

- The proponent should ensure that all tug operators used for the project have undergone T2 training

- Kitimat LNG pursue full tug escort for both inbound and outbound vessels between the project terminal in the Douglas Channel and Browning Entrance, north of the Principe Channel

- Kitimat LNG should continue its efforts to obtain information on concentrations of marine mammal populations, including Minke whales, to develop speed profiles and other mitigation measures for underwater vessel noise. This includes participation in regional initiatives, such as future Smart Oceans workshops, to obtain the best data available concerning marine mammals along the project route

The Report also includes 41 findings that describe potential federal, provincial and marine authorities’ actions to enhance the overall safety of the project:

- The proponent and its carrier companies would need to satisfy any Canadian amendments resulting from implementation of the International Maritime Organization’s International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments

- Recommendations from the Pilotage Act Review would modernize the services provided by marine pilots in Canada’s compulsory pilotage areas, including the pilotage of vessels calling at the Kitimat LNG terminal

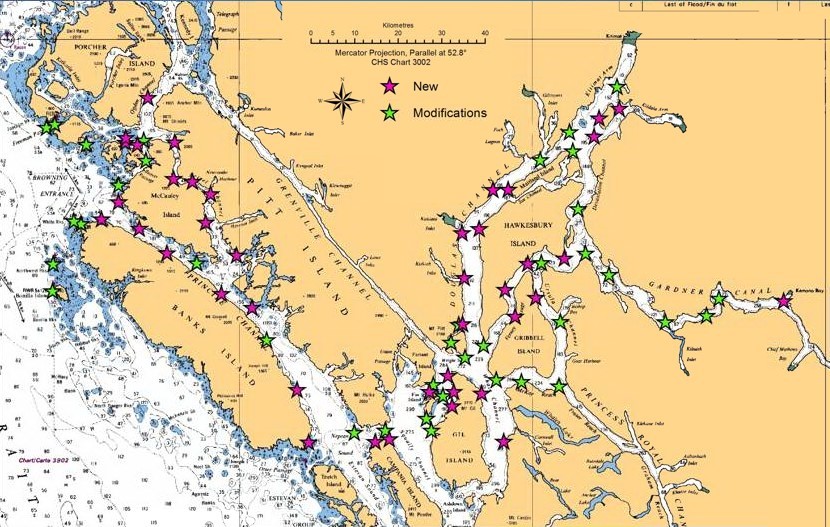

- The CHS can update nautical charts with a pilot boarding symbol if helicopter boarding is re-introduced for the North Coast

- Increased rescue towing capacity as a result of the stationing of two Emergency Towing Vessels at points along the West Coast has the potential to reduce the risk of drift grounding for LNGCs along the project route

- In consultation with the B.C. Coast Pilots and Canadian Coast Guard, Environment and Climate Change Canada may assess the need for new smart buoys to provide meteorological data to inbound vessels

A complete list of the TERMPOL Review Committee findings and recommendations in Appendix 1 can be found at the end of this document.

Introduction

Project background and description

Kitimat LNG proposes to build and operate a liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility in Bish Cove, near Kitimat, on the northwest coast of British Columbia. Bish Cove is located near the head of Douglas Channel, a fjord that penetrates approximately 130 nautical miles (241 kilometres) inland from the Pacific Ocean.

Kitimat LNG is a 50/50 joint venture between Chevron Canada Limited and Woodside Energy International. Originally, Apache Corporation was the lead investor in the Kitimat LNG project. However, in 2013, Chevron entered as an equal partner of the project, becoming the principal operator of the proposed marine facility.Footnote 2 In 2015, Apache sold its stake in the project to the Australian-based Woodside Energy, creating the existing arrangement. Footnote 3

LNG definition and context

LNG is natural gas in its liquid state. While it is comprised primarily of methane, it also includes heavier hydrocarbons and trace amounts of other compounds. When natural gas is cooled to approximately -162° Celsius at atmospheric pressure it becomes a clear, colourless and odourless liquid. LNG is cryogenic, non-corrosive and non-toxic. The process of liquefaction removes any water, oxygen, carbon dioxide and sulfur compounds from the natural gas. In liquid form, LNG is approximately 1/600th the volume of natural gas, which allows for efficient transport in purpose-built ocean carriers. The LNG is reheated and converted back into gas at the destination.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO)Footnote 4 classifies LNG as a hazardous and noxious substance (HNS). The IMO defines HNS as “any substance other than oil that if introduced into the marine environment would likely create hazards to human health, harm living resources and marine life, damage amenities or interfere with other legitimate uses of the sea.” The TRC accepts this IMO definition of LNG as a HNS, and uses this context throughout the Report. Under the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code (IMDG), LNG is classified as a liquefied flammable gas under Section 2.1, Methane, Refrigerated, Liquid or Natural Gas, United Nations, number 1972.

Project Overview

The Kitimat LNG marine terminal would be situated in Bish Cove, on the north side of the Douglas Channel near Kitimat, British Columbia. The terminal would consist of a single berth that could accommodate a range of LNG carriers (LNGCs) with cargo capacities between 125,000m3 and 217,000m3.Footnote 5 Natural gas would arrive to the export terminal via pipeline for liquefaction and then be loaded onto berthed LNGCs for export.

Project carriers would enter Canadian waters through Dixon Entrance, and use the Outside Passage for transiting to and from the terminal.Footnote 6 The route consists of the waters from Dixon Entrance north of Haida Gwaii through the Principe Channel to the Douglas Channel to berth at the proposed marine terminal. Tugs will also provide escort and berthing assistance to project vessels during their call.

The Kitimat LNG project would be delivered in two phases (LNG trains). The first LNG train would add 75 vessels to existing marine traffic in the Douglas Channel, with an additional 75 coming when the second train goes into operation. A fully executed, two-train Kitimat LNG project would export approximately 11 million tonnes per annum (MTPA).Footnote 7

Early works at the proposed site began in 2011, however full construction operations will begin once a Final Investment Decision (FID) is made.

TERMPOL report assumptions

Kitimat LNG presented potential project impact and mitigation strategies within its submission. These are based on the full build scenario and maximum size carriers able to call at the terminal, specifically the 217,000 m3 Q Flex carriers. The proponent’s rationale is that this will sufficiently account for smaller LNGCs that could also potentially call at the terminal.

Project carriers will operate in waters under Canadian jurisdiction and must comply with Canada’s regulatory regime for safe operation. Legislation, including the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 (CSA, 2001) sets out the requirements and responsibilities for safe vessel operation, including monitoring and enforcement. Moreover, the CSA, 2001 implements certain international conventions in Canada. In addition to Canadian and international requirements, project carriers will also comply with Kitimat LNG’s internal carrier vetting and terminal procedures, expressed in detail later in the report.

The TERMPOL report is based on existing traffic data and projections. It does not take into account the impact other potential projects would have on the Kitimat LNG project which would operate along the same waterway.

Environmental Assessment process

The Kitimat LNG project meets the requirements for an environmental assessment under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012, and B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Act, 2002. The proponent’s LNG facility was granted a Federal Environmental Assessment Certificate (EAC) in 2008, and the Government of B.C. issued a Provincial EAC in 2009. These certificates are subject to follow-up monitoring to verify accuracy of the assessment, and determine the effectiveness of mitigation measures.

TERMPOL process and review report

TERMPOL refers to the ‘Technical Review Process of Marine Terminal Systems and Transshipment Sites’ and is set out in TC’s Technical Publication TP 743E, TERMPOL Review Process 2001Footnote 8.

TERMPOL is a voluntary review process for proponents proposing to build and operate marine terminal systems for bulk handling of oil, chemicals and liquefied gases. The process considers the marine transportation components of a project, including the movement of vessels through Canadian waters and channels, and approaches to marine terminal berths to load or unload oil or gas. The intent of the process is to improve, where possible, the elements of a proposal which could, in certain circumstances, threaten the integrity of a vessel’s hull during navigation and/or cargo transfer operations at the terminal.

Throughout the process, the proponent works with the TRC. Committee members represent federal departments and authorities with applicable expertise or responsibilities. The TRC reviews the proponent’s TERMPOL submission and provides a report with recommendations and findings. The report:

- offers technical feedback and TRC perspectives

- may propose improvements to enhance the marine safety of a project and/or address any site-specific circumstances

The success of the TERMPOL process is largely dependent on the proponent’s adherence to the procedures described in the TERMPOL Review Process 2001 guidelines TP 743E (Review Guidelines), and the quality of data and analysis it submits to the TRC. The proponent is responsible for ensuring its surveys and studies meet the highest industry and international standards.

The TERMPOL process is not a regulatory instrument. No approvals or permits are issued as a result of the TERMPOL review or report. As such, the TERMPOL report should not be interpreted as a statement of government policy or federal government endorsement. Although TERMPOL report findings and recommendations are not binding, a proponent may integrate the suggested improvements into their engineering, planning and design.

The TERMPOL Review Process does not replace or reduce the safety, security, and environmental requirements of any Acts and/or Regulations that are in effect or subject to amendments. The process will not approve or reject the project. Kitimat LNG must obtain any such approvals from the appropriate regulatory authorities by following their own specific processes. The proponent and any associated carrier servicing an approved project would need to comply with all applicable legislation and regulations, including future amendments. TC and other agencies may also use the work and report of the TRC to identify potential regulatory improvements or special measures.

In addition to securing environmental assessment certificates, Kitimat LNG will need to obtain a suite of regulatory permits from the provincial government, including a LNG facility permit from the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission (BC OGC). Although an export license was granted by the National Energy Board in December 2013, Kitimat LNG must also obtain additional federal permits and approvals, such as Navigation Protection Act approval from TC.

Scope of TERMPOL

The TERMPOL Review Guidelines set out a maximum possible scope of assessment for vessel safety and the risks associated with vessel manoeuvres and operations. The proponent, in consultation with the TRC, selected the most appropriate scope for the project after considering existing shipping activities in the area and/or unique circumstances. The TRC and the proponent agreed on the following scope for the TERMPOL Review of the project:

- Vessel operations in Canadian waters along the proposed shipping routes to and from the Kitimat LNG marine terminal

- The analysis area includes both approach routes, from the western point of Dixon Entrance and from the southern entrance of the Hecate Strait

- Project LNGC characteristics, navigability, vessel routes in Canadian waters, other waterway users, the marine terminal and cargo transfer operations

The TERMPOL report examines:

- studies, surveys and technical data provided by Kitimat LNG in support of the TERMPOL Review Guidelines

- existing national and international regulatory frameworks to ensure safe carrier operations

The report assesses the proposed project’s marine transportation operations within the context of the existing marine regulatory regime, programs and services. The report does not examine land infrastructure such as natural gas receiving and LNG production facilities, or associated infrastructure such as power supply, water supply, and waste collection. The report notes that new measures, such as helicopter pilot boarding, could affect project operations. The appraisal allows the proponent to liaise with appropriate federal authorities to address new or changing issues, concerns, or priorities related to the project’s marine transportation components.

As set out in the TERMPOL Review Guidelines, Kitimat LNG submitted the studies, surveys, and technical data identified in Table 1 for TRC review and analysis. The surveys and studies were presented in the following order:

|

Number |

TERMPOL Survey/Study Title |

|---|---|

|

3.1 |

Introduction |

|

3.2 |

Origin, Destination and Marine Traffic Volume Survey |

|

3.4 |

Offshore Exercise and Offshore Exploration and Exploitation Activities Survey |

|

3.5

|

Route Analysis, Approach Characteristics and Navigability Survey |

|

3.6 |

Special Under Keel Clearance Survey |

|

3.7 |

Transit Time and Delay Survey |

|

3.8 |

Casualty Data Survey |

|

3.9 |

Ship Specifications |

|

3.10 |

Site Plans and Technical Data |

|

3.11 |

Cargo Ship Transfer |

|

3.13 |

Berth Procedures and Provisions |

|

3.15 |

General Risk Analysis and Intended Methods of Reducing Risks |

|

3.18 |

Contingency Planning |

|

3.20 |

Hazardous and Noxious Liquid Substances |

The proponent and TRC jointly agreed with the omission of two studies that are not applicable to the project:

- (3.14) Single Point Mooring Provisions

- (3.19) Procedures and Oil Handling Facilities Requirements

As the proponent submitted the Fishery Resources Survey (3.3) as part of the Environmental Assessment process, it is not part of its TERMPOL Submission. The Port Information Book (3.16) and Terminal Operations Manual (3.17) will be submitted at a later date, as that level of detail is not available in the early planning stages of a project. The TRC has advised Kitimat LNG that they must submit each of these documents at least six months prior to the start of project operations.

Methodology

On July 27, 2005, Kitimat LNG formally requested a TERMPOL review. TC approved the request and met with the proponent to discuss the scope of surveys and studies. Investor restructuring and uncertainty around the project’s viability delayed the proponent’s TERMPOL submission. However, on June 13, 2016, the proponent submitted its TERMPOL package of surveys, studies, technical data, and analysis related to the marine transportation components of the project. TC, as chair of the TRC, distributed copies of the package to committee members for review and comment.

The TRC is comprised of representatives from:

- Transport Canada (TC)

- Fisheries Oceans Canada (DFO), including:

- Canadian Coast Guard (CCG)

- Canadian Hydrographic Services (CHS)

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC)

- Pacific Pilotage Authority (PPA)

- British Columbia Coast Pilots (BCCP)

These member departments and authorities collaborate to deliver the federal government’s comprehensive regulatory framework. This helps to ensure Canada’s marine transportation system is safe, secure and environmentally responsible. The BC OGC and Natural Resources Canada also contribute input to the TRC, where necessary.

The TRC reviewed the proponent’s TERMPOL Submission from the perspective of their individual mandates, regulatory authorities and expertise. After a thorough review, the relevant authorities contribute to and approve the TERMPOL Report, which contains a number of recommendations and findings. By definition:

- ‘Recommendations’ propose suggested actions for Kitimat LNG

- ‘Findings’ highlight observations about the project or actions that may be undertaken by appropriate authorities

The TRC bases the analysis and commentary in this report on the information, documentation, and technology available at the time it was written. The project could be subject to reanalysis if the scope or timeline changes significantly. It is recommended this report be read in conjunction with the TERMPOL Review Process 2001 guideline (TP 743E).

Recommendation 1: Kitimat LNG should provide relevant authorities with advance notice if changes are made to project commitments, operational parameters or characteristics.

Analysis

The TERMPOL Submission (the submission) details the proponent's plans and mitigations as they relate to the marine transportation components of this project including attending carriers.

The TERMPOL Report (the report) reflects the TRC's analysis of the proponent's plans and mitigations. The report proposes recommendations and findings specific to the project that apply to project carriers, routing and terminal safety. Some recommendations can be implemented directly by the proponent, while others will involve working with appropriate authorities.

The TRC expects the proponent to deliver on the plans and mitigations it proposes within the submission because they are important elements of the TRC’s assessment of project’s safety.

The proponent is encouraged to adopt and implement the recommendations included in this report. The TRC recognizes that adequate lead time and discussion will be required where formal enhancements to the current marine safety regime are proposed.

This section of the report reviews the project details examines the key commitments made by Kitimat LNG in their submission. Specifically, the report analyzes:

- Vessel information

- Route information

- Terminal operations

- LNG/oil spill preparedness and response

Finding 1: Implementation of TERMPOL Review Committee recommendations may require individual agreement between the proponent and the responsible authorities.

Quantitative Risk Assessment

TERMPOL Element 3.15 was prepared by marine risk assessment specialists DNV GL for Kitimat LNG as part of the TERMPOL Review Process. Scenarios were developed that analyze the frequency and consequence of a potential LNG release. The proponent’s Transit Quantitative Risk Assessment describes incident frequencies and consequences of a loss of containment from a laden LNGC at points along the shipping route. The Terminal Quantitative Risk Assessment describes incident frequencies and consequences of a loss from a laden vessel berthed at the Kitimat LNG terminal in the Douglas Channel. Incident frequencies were calculated for the following events:

- Collision

- Powered grounding

- Drift grounding

The results were then combined in a single geospatial graphic to assess the potential safety risk from the proposed terminal sites. Results from the study have informed a suite of mitigation measures that have been proposed by Kitimat LNG. These include a number of specific mitigation measures to reduce the risks associated with collision, drift and powered grounding, as well as marine terminal operations. These measures are discussed in further detail in Section 3.2.4 of this report.

In calculating the frequency of all incident types, Kitimat LNG made the following assumptions:

- The design ship for this Project is a 217,000 m³ Q-Flex membrane type with approximately 315 m length overall (LOA)

- Impact from very steep angles (less than 22.5° and greater than 157.5°) will not penetrate the LNGC cargo tank

- The following size distribution of holes that would lead to a spill is: 23% of holes are 250 mm, 45% of holes are 750 mm and 32% of holes are 1100 mm

- All accident releases will ignite. Furthermore, 30% of collision incidents resulting in an accidental release will form a flammable gas cloud and ignite while the remaining 70% ignite immediately forming an LNG pool fire. The delayed ignition probability for grounding incidents that lead to an accidental release of LNG is 100%. Delayed ignition would allow a flammable gas cloud to reach its farthest extent prior to ignition and flash back source

- The terminal is built with good ignition controls based on the Atkins on-site ignition model

HAZID workshop

Hazard identification is the first step as part of the proponent’s risk analysis. In April 2014, Kitimat LNG held a two-day Hazard Identification (HAZID) workshop to identify potential navigational and loading hazards, as well as to discuss safeguarding measures for the transit route and terminal operation. The HAZID workshop presented a systematic approach to the identification of hazards and risk associated with carrier routes and berthing at the project terminal. The workshop participants were able to provide the proponent with local knowledge about the route and terminal operations to be incorporated into the risk assessment.

Representatives from TC, PRPA, BCCP, CCG, Seaspan, Apache, as well as from the Gitga’at, Haisla, and Heiltsuk First Nations took part in the discussion.

The proposed project route was divided into eight nodes; safeguards and mitigation measures were discussed considering the following events:Footnote 9

- Collision

- Drift grounding

- Powered grounding

- Striking the loading platform

- Striking the trestle

- Overfilling the cargo tank

- Striking the vessel while loading

- Release from the loading arms

The workshop highlighted several areas of concern for local residents and stakeholders, including:

- tug assistance strategies both along route and at the terminal

- additional navigational aids and new land-based radar

- traffic separation schemes and limiting passing and overtaking

- vetting processes

The proponent has advocated for solutions to the above suggestions within its TERMPOL submission. In some instances, members of the TRC have directly addressed these perceived gaps, while others are contained in the TERMPOL report in the form of findings and recommendations.

Vessel information

This section provides an overview of the Canadian and international laws and regulations that LNGCs must comply with. Three important Acts and pursuant regulations are:

The Canada Shipping Act, 2001

This is the main legislation that regulates safety in marine transportation and protects the marine environment from vessel-source pollution in Canada. The CSA, 2001 implements several international conventions in whole or in part through its regulations and seeks to balance vessel safety and marine environment protection with the need for maritime commerce. It also provides authority to investigate and, if necessary, to prosecute using various tools and actions.

The Pacific Pilotage Regulations of the Pilotage Act

This establishes marine zones along the B.C. coast where vessels are subject to mandatory pilotage.

The Marine Transportation and Security Act (MTSA)

This provides for the security of marine transportation and applies to prescribed vessels, ports and marine facilities in Canada, Canadian vessels outside of Canada, and marine installations and structures.

Each project carrier will have to meet the requirements of the IGC Code and hold a valid Certificate of Fitness for the Carriage of Liquefied Gases in Bulk. Project carriers will also be subject to other certifications while in Canadian waters, as required by TC, classification societies, and the IMO.

Modern carriers are equipped with the latest navigational systems and radar systems that provide timely information to facilitate safe navigation. Further, Kitimat LNG should ensure that all project carriers meet the Emergency Towing Procedures requirements of SOLAS Regulation II-1/3-4.

Carrier tank types

The Kitimat LNG terminal berth would accommodate two common types of double-hulled carriers with different tank types. Both tank types effectively maintain cryogenic temperatures needed for safe LNG storage and transport. Each tank type has unique characteristics:

Kvaerner-Moss spherical tank type

This is typical for smaller and mid-size carriers up to 140,000m3, as larger-capacity spherical tanks would limit a vessel’s external dimensions and prevent it from meeting port thresholds. Moss tank vessels are more susceptible to effects of high winds, which can pose challenges during berthing.

Membrane tank type

This vessel has a lower main deck profile and is less susceptible to high winds. These tanks are more common in vessels ranging from 140,000m3 to 265,000m3 in size.

Design vessels

The Kitimat LNG terminal plan features a single LNG loading berth that is able to accommodate both Moss tank LNGCs and Membrane tank LNGCs. Kitimat LNG plans for vessels with tank capacity between 125,000 m3 to 217,000 m3 to berth at the terminal (see Table 2). The overall length of the ships being considered is between 272 m and 315 m.

Although the proponent expects the Q Flex carrier to be the largest vessel to visit the terminal, other carriers of varying sizes may also call. Accordingly, the design vessels of the submission represent only a general range of the terminal’s capabilities – what is referred to as the “typical expected vessel.”

|

Description |

Project Design Vessel Maximum |

Project Design Vessel Minimum |

|---|---|---|

|

Capacity, m3 |

217,450 |

127,737 |

|

Length Overall, m |

315 |

272 |

|

Ballast draught, m |

9.7 |

9.0 |

Carrier speed

As part of their submission, Kitimat LNG has detailed the speed profile of a vessel calling at their proposed marine terminal. At all times, project carriers must maintain safe speed, as per Rule 6, Part B – Steering and Sailing Rules, found in Schedule 1 of the Collision Regulations created under the CSA, 2001. Kitimat LNG states that the average LNGC service speed at sea for its design vessels is between 18 to 21 knots, depending on hull form and installed engine power.Footnote 11 However, it is necessary for speed to be reduced for safe transit within Canadian waters.

To outline the approximate speed of a vessel at specific points along the route, Kitimat LNG has divided the route into two segments:

- The Open Water Section which includes the section from Dixon Entrance to Browning Entrance

- The Channel Section which includes Dixon Island, Otter Channel, Lewis Passage, Emilia Island, and Wright Sound

The proponent estimates that carriers will travel at speeds between 12 and 17 knots in the Open Water Section of the route, and 8 to 14 knots in the Channel Section. The estimated time for transit to the Kitimat LNG terminal is 11 to 18.2 hours.Footnote 12 In practice, however, the speed profile for carriers may differ because it will be dependent on factors such as environmental conditions (e.g. weather, sea state) as well as other marine traffic along the route.

In addition, vessel speed may be limited in sections where tugs are used in escort. Simulations revealed the maximum speed where a tug can be effective in case of an emergency is in the range of 10 to 12 knots. Escort at higher speeds would require a custom built tug.

Recommendation 2: LNGCs used for the Kitimat LNG project should travel at a safe speed that is mutually agreed upon by the Master and the Pilot, while taking into account the speed capability of tugs in escort.

Recommendation 3: If Kitimat LNG is inclined to pursue transit speeds faster than 12 knots within the Channel Section of the route, they should work with tugboat providers to develop a custom tug design that is still able to be effective in the event of an emergency at a higher speed.

Carrier manoeuvring

Industry best practices have established the appropriate timing for certain actions that must be taken at different points of a carrier transit, including:

- preparing the engine for immediate manoeuvre

- manning the engine room

- readying the crew to respond to potential adjustments in carrier speed (i.e. stand-by mode)

The TRC notes that the crew should be in full attendance at the carrier’s manoeuvring stations (i.e., bridge, engine control room and steering gears) at critical times, such as:

- at least one hour before arrival in Dixon Entrance, the crew must ensure the carrier is fully manoeuvrable to take appropriate action in the event of unforeseen scenarios

- manning the engine room to maintain schedule and berthing at the terminal as close to the estimated time of arrival as possible

- manning the engine room to ensure the vessel can depart unexpectedly if an emergency occurs while loading/unloading

Recommendation 4: The proponent should include in its Port Information Book that Masters must ensure project carriers are ready for immediate manoeuvring at all times, especially during critical points of transit. The engine room should also be fully manned at least one hour before arrival in Canadian waters, and remain manned until the vessel is alongside the marine terminal.

Canadian requirements and international conventions

Project carriers must comply with the safety and environmental protection requirements of:

- International conventions (such as the IMO)

- Canada’s marine safety regulatory regime, notably the CSA, 2001 and its regulations while in Canadian waters

- The International Code for the Construction and Equipment of Ships carrying Liquefied Gases in Bulk (IGC code)

Canadian and international requirements address areas such as:

- safe vessel design and construction

- safe manning

- crew qualifications and training

- working conditions

- safety management systems

- radio communications equipment and equipment for safe navigation including Electronic Chart Display Information System (ECDIS) and AIS

- voyage planning

- vessel reporting

- rules to prevent collisions

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS)is the main international convention for vessel safety. The main objective of SOLAS is to set specific minimum standards for construction, equipment, and operation of ships compatible with their safety. Administrations certify and regularly inspect vessels trading internationally (including LNGCs) that fly their flags, as set out in the relevant international conventions.Footnote 13

Flags and registries link each vessel with a nationality, or Flag State. Under the registries the vessels are required to follow the applicable regulations of the country where they are registered. The country where the vessel is registered is responsible for ensuring the vessel complies with applicable national laws and international conventions.

LNG carrier construction

The construction of a LNGC must comply with the requirements of the Flag State as well as the appropriate instruments of IMO conventions and codes. LNGCs must also comply with the version of the International Code for Construction and Equipment of Ships Carrying Liquid Gases in Bulk (IGC Code) in force at the time of their construction, and the guidelines of classification societies. Guidelines and recommendations are also issued by the Oil Company International Marine Forum (OCIMF) and the Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators (SIGTTO)

IGC Code includes requirements for the following items and controls:

- Cargo containment construction materials

- Cargo pressure and temperature control

- Environmental control

- Fire protection and extinguishment

- Personnel protection

- Capacity limits for cargo tanksFootnote 14

If a carrier meets every requirement, the Flag State will issue a Certificate of Fitness for the Carriage of Liquefied Gases in Bulk. This certificate is valid for five years.

Shipping conventions

Carriers must comply with all shipping-related IMO conventions that Canada has ratified and adopted into legislation, including the:

- SOLAS Convention

- International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL)

- Standards for Training, Certification and Watchkeeping (STCW) Convention

- Maritime Labour Convention 2006

According to MARPOL Annex 1 Regulation 1(4), carriers must:

- have an International Oil Pollution Prevention Certificate

- possess a Shipboard Marine Pollution Emergency Plan (SMPEP), which incorporates the Shipboard Oil Pollution Emergency Plan (SOPEP)

Classification Societies

Classification Societies perform statutory inspection and certification functions on vessels around the world and have extensive expertise in the construction and operation of modern ships. TC has entered into formal agreements with certain Classification Societies, under the authority of section 12(1) of the CSA, 2001. These agreements delegate certain statutory inspection and certification functions. Seven Classification Societies are currently able to conduct vessel inspection and certification in Canada.

Through the Delegated Statutory Inspection Program (DSIP), vessel owners may enroll to have the third-party Classification Societies perform these functions on their vessels. The DSIP is mandatory for vessels 24 m in length and above in Canada.

TC conducts oversight audits of delegated vessels and the Recognized Organization in accordance with the DSIP. When a vessel is delegated to receive a statutory inspection and certification service from a Recognized Organization (RO), TC continues to monitor the performance of both vessel operators and the RO through planned and unplanned risk-based compliance inspections.

Port State Control

Canada has measures in place under CSA, 2001, which help ensure large foreign vessels (including project LNGCs) entering Canadian waters comply with international and Canadian requirements and do not pose an undue risk to safety or the environment.

Port State Control is TC’s primary means for enforcing the CSA 2001, the Marine Transportation and Security Act, and applicable international conventions Canada has incorporated into its laws. This is a vessel inspection program established under the IMO, whereby countries sharing common waters agree to share inspection responsibilities and information. For example, Canada is a Port State for foreign vessels that enter our waters and we inspect them according to international agreements. Moreover, Canada is a member of:

- The Paris Memorandum of Understanding, an agreement between coastal countries of the North Atlantic

- The Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding governing the Asia-Pacific region

The IMO and the International Labour Organization provide the regulatory framework for the Port State Control program. The objective is to inspect foreign vessels of all types, including tankers, against international standards to detect and eliminate sub-standard vessels and the threat that they pose to life, property, and the marine environment.

It is TC’s policy to inspect or audit every foreign tanker vessel calling at a Canadian port on its first visit to Canada, and at least once a year thereafter. Canada considers LNGCs as tankers for inspection purposes, making them subject to this policy. TC specifically targets vessels that have previous history of non-compliance, a poor safety record, and which are generally more than 12 years old for more detailed or expanded inspections. Inspections may include:

- vessel certificates and documents (crew training, ballast water reports, etc.)

- confirmation of watertight/weather tight condition, stability, and loading or discharge plans

- determination as to whether deficiencies found by a Port State authority at a previous inspection have been corrected

- structural condition (exterior as well as inside ballast tanks)

- emergency system and emergency preparedness measures

- propulsion machinery

- pollution prevention measures

When inspectors find defects, TC may use a range of enforcement actions and depending on the severity of the infraction, can:

- require the vessel to perform repairs before sailing

- detain the vessel at port

- fine the ship owner

- prosecute the ship owner under the CSA 2001

Transport Canada publishes all defects on the Port State Control database. TC may also impose fines for non-compliance under Administrative Monetary Penalties and Notices (CSA, 2001) Regulations. Even minor defects have financial consequences for the vessel’s owner or operator, as once defects are noted on the Port State Control database a vessel’s risk profile may change leading to increased inspections at ports around the world. This makes Port State Control an effective incentive for ship owners to comply with international conventions and national regulations. TC would perform compliance inspections of project carriers as part of its regular inspection regime.

LNG carrier vetting criteria

Kitimat LNG will require vessels to gain approval through Chevron’s ‘LNG Carrier Acceptance Program’ before being able to proceed to call at the Project terminal. The acceptance process is divided into two parts:

- The Compatibility Assessment, which assesses a ship’s physical particulars, including deck arrangement and cargo and mooring systems, in order for the vessel to be deemed adequate to conduct cargo transfer at the terminal

- The Quality Assessment, which requires a quality assessment of the vessel, owner, and technical manager; some controls are internationally-accepted safety benchmarks introduced by independent bodies such as the Oil Companies International Marine Forum (OCIMF), while others are specific to Chevron’s in-house LNG Carrier Acceptance Program

The OCIMF is a voluntary association of oil companies. It promotes the safe design and operation of tankers and terminal operations related to crude oil, oil products, petrochemicals and gas. The association regularly represents the views of industry at the IMO and has become an advocate for marine safety standards and regulation.

For instance, the Ship Inspection Report Programme (SIRE) is a voluntary inspection process OCIMF members that employ tankers/barges pay for as part of their business. The OCIMF member companies commission vessel inspections by an accredited SIRE inspector. The inspector then uploads the SIRE report to the SIRE database, which OCIMF members and partners can access for a small fee. Industry adherence to the SIRE programme promotes continuous improvement. It is standard that all carriers calling at the project terminal possess a SIRE certificate that is no more than six months old.

The OCIMF has also introduced the Tanker Management Self-Assessment Survey (TMSA) as best-practice guidance to help vessel operators assess, measure and improve their safety management systems. The guidance document allows operators to self-assess against 12 key performance indicators. The TRC recognizes the value of the TMSA as an added carrier safety measure.

Finding 2: The Ship Inspection Report Programme (SIRE) and Tanker Management Self-Assessment Survey (TMSA) are important tools terminals and energy companies use to enhance carrier safety and exceed minimum regulatory requirements.

Recommendation 5: As part of their Carrier Acceptance Program, Kitimat LNG should ensure all carriers that call at the terminal possess a SIRE certificate that is no more than six months old.

As part of the Quality Assessment, the proponent will require:

- results of the current TMSA to assess the technical manager’s Safety Management System

- a Vessel Inspection Report (VIR) loaded on the SIRE website and reviewed to assess safe operations of LNGC. The review may require that a new VIR be performed if it is outside the age requirements for the validity of the VIR

- an Online Crew Matrix loaded on the SIRE website and reviewed to verify adequate experience, including STCW requirements and SIGTTO recommendations

- LNGC Class Status to be in accordance with Class rules and recommendations

- Port State Control Inspections and detentions, as well as casualty data to assess safe operation of the LNGC

- Terminal Feedback to assess safe operation at terminals

- Vessel Age and Condition Assessment Program certification to ensure it is within Kitimat LNG acceptance criteria

- compliance with International Ship and Port Facility Security Code

Additionally, LNGCs used for the Kitimat LNG project, will be subject to the following regulatory body inspections:

- Flag State

- Port State Control

- Class

- Owners

- Third-Party Vetting Companies

The proponent has not stated whether it will own and operate the LNGCs that call on the terminal. If the proponent charters from the open market, or acquires new vessels, it will be responsible for ensuring any carrier meets all required legislation and best-practice criteria.

Ballast water requirements

The project would involve project carriers up to 217,000 m3 arriving ballasted with sea water. These carriers must comply with Canada’s Ballast Water Control and Management Regulations, including and as applicable, the IMO’s International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments. The Ballast Water Control and Management Regulations came into force in 2011, and require vessels to exchange their ballast water under the conditions set out by the regulations. Four management methods are permitted, as outlined in section 4(1) of the BWCM Regulations:

- Ballast water exchange

- Treatment using a ballast water management system (BWMS)

- Transfer to a reception facility

- Retention on board the ship

In 2010, Canada signed on to the International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments, 2004, which has reduced the risk of aquatic species invasions compared to Canada’s existing regulations. Formerly, it was required that ballast water exchange take place at least 200 nautical miles from the shore where the water is at least 2,000 metres deep. Now, as of September 8, 2017, the Convention will require new ships to limit the number of viable organisms they discharge in ballast water through the use of a treatment system aboard the vessel. A ship-specific schedule aims to spread compliance by existing ships over the next seven years. As it will not be possible to use ballast water exchange to meet the Convention’s standard, most ships are expected to fit BWMS to comply. TC is participating in ongoing efforts at the IMO to develop a roadmap for applying the Convention.

Vessels bound for a Canadian port, offshore terminal or anchorage must submit a Ballast Water Report to TC to demonstrate compliance with the regulations. Upon arrival, Ballast Water Reports are processed by TC inspectors. If the vessel is flagged for having a poor compliance record, or carries a high environmental risk profile, the vessel may be subject to further inspection by TC inspectors. Vessels can also be randomly inspected to ensure compliance or for demonstration of salinity measurement methods.

Note: Reports must include information on all ballast tanks, whether empty, ballasted, or have residuals.

In the event of non-compliance, TC may use a range of enforcement tools depending on the severity of the infraction. These include verbal advice, written warning, retention of ballast water, detention, and in certain cases, prosecution under the CSA, 2001.

Finding 3: The proponent and its carrier companies would need to satisfy any Canadian amendments resulting from implementation of the International Maritime Organization’s International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments.

Vessel security requirements

Vessel security requirements are administered through national and international regulatory frameworks beyond the scope of the TERMPOL review. All vessels must comply with national legislation and international frameworks for vessel and terminal security such as the Canadian Marine Transportation Security Regulations (MTSR).

Recommendation 6: Kitimat LNG should liaise directly with Transport Canada’s Marine Security Branch to ensure compliance with all aspects of the Marine Transportation Security Regulations.

Automatic Identification System (AIS)

The Navigation Safety Regulations created under the CSA, 2001 and SOLAS requires vessels engaged on an international voyage of 300 gross tonnes or more, and domestic vessels of 500 gross tonnes or more, to be fitted with an AIS.Footnote 15 AIS automatically provides information, including the vessel’s identity, type, position, course, speed, navigational status and other safety-related information, to AIS-equipped shore stations, other vessels, and aircraft. AIS improves a vessel’s situational awareness and greatly enhances the traffic-monitoring capabilities of the CCG’s AIS-equipped Marine Communications and Traffic Services (MCTS) centre, located in Price Rupert. The use of AIS would be mandatory for all project carriers.

Note: These requirements do not apply to fishing vessels.

As of 2018, Prince Rupert MCTS is finalizing their AIS data capture and processing protocol. AIS is operational and 99% is integrated into the traffic management system. The CCG is working to fill in dark spots, as well as determine areas for enhanced monitoring capability (radar) for the North Coast. This includes study into areas such as Whale Channel, south Douglas Channel and south Grenville Channel.

Finding 4: The Canadian Coast Guard will continue to improve upon the existing AIS system on the North Coast to enhance monitoring capability

Crew certification/manning

Project LNGCs must be equipped and manned to uniformly high industry standards. Kitimat LNG will ensure project carriers are staffed according to the SOLAS Safe Manning Document. The proponent expects shippers of its cargo to follow the LNG shipping practice of aligning certification and experience levels for deck and engineering officers with the Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators (SIGTTO) Office Experience Matrix. The SIGTTO Experience Matrix considers a number of factors, including length of sea service, experience by rank, and experience in LNG operations.

Kitimat LNG also understands project carriers must meet all required elements of the Marine Personnel Regulations (MPR) created under the CSA, 2001, which feature minimum experience and training requirements for LNGC crew. Under the MPR, officers must hold a valid Liquefied Gas Tanker Familiarization certificate or endorsement to work onboard a LNGC. To obtain this license or endorsement, the applicant must fulfill training and experience requirements.

Specifically, a new applicant must successfully complete approved training in LNG carrier familiarization. This includes spending at least three months onboard an LNG carrier as part of this mandatory training. Assigned duties relate to the loading, discharging or transferring of cargo, and the operation of cargo equipment. Further, the applicant would need to hold a certificate in basic marine first aid, in addition to a Marine Emergency Duties (MED) certificate with respect to the IMO STCW.

Canadian Marine Emergency Duties training courses are aligned with STCW Convention and STCW Code requirements to ensure adherence to international standards.

- MED training includes basic safety training, firefighting operations and use of survival craft in emergency situations

- The Liquefied Gas Tanker Familiarization certificate or endorsement renewal process features similar minimum requirements for emergency training

Finding 5: The TERMPOL Review Committee supports Kitimat LNG’s commitment to adhere to Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators (SIGTTO) Officer Experience Matrix certification and experience levels.

Route information

Overall route

This section outlines the proponent’s proposed shipping routes to the terminal berth at Bish Cove in the Douglas Channel, along with relevant background on marine activities and authorities in the area.

Carrier route overview

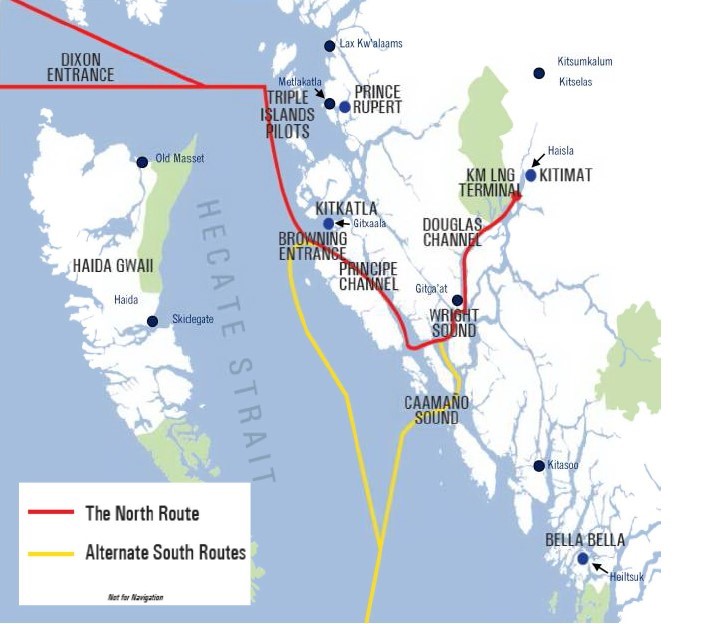

Kitimat LNG has proposed that project carriers transit through Canadian waters via two routes:

- The North Route, via Dixon Entrance north of Haida Gwaii

- The South Route by way of Hecate Strait, entering either at Browning Entrance or Caamano Sound

However, Kitimat LNG states in their submission that they will not use the South Route for project operations.Footnote 16 There are a number of reasons as to why the South Route is not viable, including:

- inclement weather and tidal conditions throughout the year

- the need for additional NavAids

- the need for a new pilot boarding station

Recommendation 7: The TRC supports Kitimat LNG’s commitment to not use the South Route. Use of this route should not be attempted without consultation with the PPA, confirmation of adequacy of NavAids, and full mission bridge simulations.

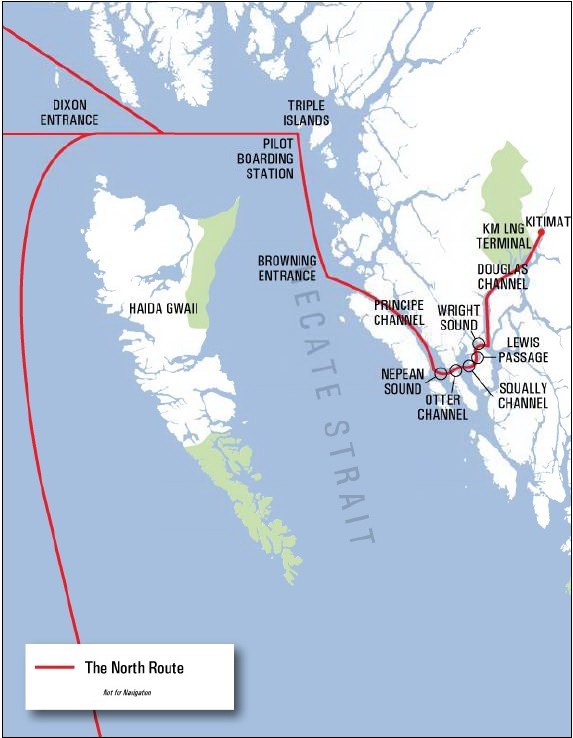

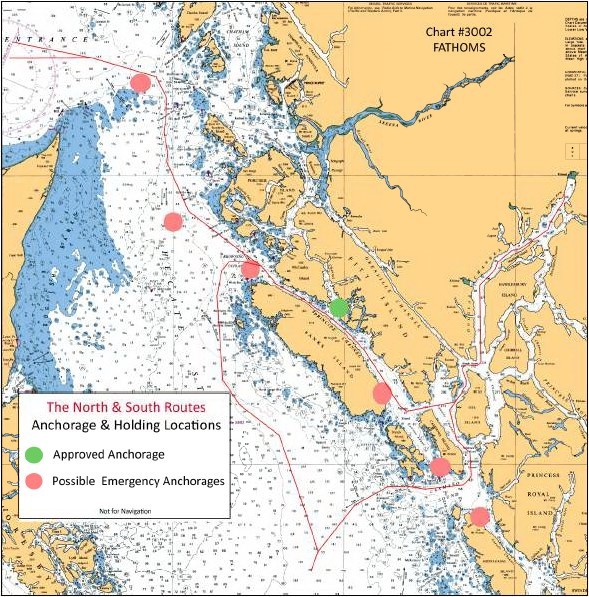

Figure 1 – The North Route:Footnote 17

Figure 2 – The South Route:Footnote 18

Kitimat LNG has stated it will use a passage plan and electronic navigation equipment to follow the best possible route, accounting for traffic, as well as weather and other navigational hazards that may be encountered. The proponent indicates that Project vessels will travel at mid-channel along the proposed route, unless there is a navigational safety reason not to do so.

The north route

LNGCs transiting via the north route will:

- arrive from the Pacific Ocean to enter the marine route through the Dixon Entrance

- take on a pilot near the Triple Island pilot boarding station, either by boat or by helicopter, before travelling south to Browning Entrance and into Principe Channel

- at the south point of Principe Channel, transit through Otter Passage, Squally Channel, Lewis Passage, and then across Wright Sound

- head north in Douglas Channel and enter Kitimat Arm to reach the Project marine terminal at Bish Cove

Kitimat LNG has stated it will use a passage plan and electronic navigation equipment to follow the best possible route, accounting for traffic, as well as weather and other navigational hazards that may be encountered. Kitimat LNG indicates that Project vessels will travel at mid-channel along the proposed route, unless there is a navigational safety reason not to do so.

The proponent must always comply with the Canadian Collision Regulations when in Canadian waters. Rule 9 of the COLREGS states that when a vessel is proceeding along the course of a narrow channel, it will keep as near to the outer limit which lies on the starboard side, as is safe and practicable.

Inbound LNGCs will initiate End of Sea Passage (EOSP), by slowing the vessel from full speed to a manoeuvring speed at a safe position to the west of Triple Island.Footnote 19 Before the marking of EOSP, a number of routine provisions and safety checks are done to prepare for passage through Canadian waters. The engine room should also be fully manned before the process is commenced. Kitimat LNG should ensure EOSP is made in time to accommodate pilot boarding from boat or by helicopter, outlined in the PPA “Notice to Industry” (08/2015) and described in more detail in the following section.

Pilotage

Pilotage involves licensed marine pilots boarding vessels in specific areas to navigate through difficult waterways to avoid local hazards. Pilots provide extensive expertise and knowledge of a local waterway for vessels travelling to and from Canadian ports. All coastal areas below the 60th parallel of the country fall under the jurisdiction of one of four Pilotage Authorities that are governed by the Pilotage Act:

- Atlantic Pilotage Authority

- Great Lakes Pilotage Authority

- Laurentian Pilotage Authority

- Pacific Pilotage Authority

These authorities establish compulsory pilotage areas, in which every ship over 350 gross tons and every pleasure craft over 500 gross tons must take local marine pilots on board before they can enter harbours or busy waterways. The local pilots must have expertise in navigation of local waterways and the handling characteristics of the vessels they are guiding.

Figure 3 – Compulsory Pilotage Areas in British Columbia

The authorities also regulate the requirements for certain classes of vessels, including LNGCs. The Pacific Pilotage Regulations under the Pilotage Act govern pilotage activities in Canada’s western waters. The PPA is a federal Crown corporation whose mandate is to administer marine pilotage service in Canadian waters off the B.C. coast.

In December of 2017, the Government of Canada announced a review of the Pilotage Act, through the Ocean’s Protection Plan. Efforts will be made to modernize the Pilotage Act to align with the goal of creating a world-leading marine safety system.

Released in May of 2018, the Pilotage Act Review has provided a list of recommendations centered on modernising the services and the management approaches within Canada’s compulsory pilotage areas. More specifically, the Pilotage Act reinstated its emphasis on safety and efficiency of delivery of pilotage services. The Review has also touched upon a variety of issues consisting of but not limited to:

- addressing regional inconsistencies in medical standards applied to pilots

- updating fine structures for elusion from pilotage services

- considering new, technology-augmented pilotage regimes

- expanding Transport Canada’s role in safety regulatory-making powers to advance a safe and streamlined management regime