Vehicle Regulation Directorate

RS-2008-02

March 2008

BACKGROUND

There is considerable evidence that cell phone use impairs driving performance, and that this impairment significantly increases collision risk ( e.g. , Harbluk et al., 2002; 2007). Furthermore, the majority of Canadians believe that distracted driving is a serious road safety problem (Vanlaar et al., 2007). Little is currently known about the actual nature and amount of phone use while driving on Canadian roads. The present study tried to quantity this by collecting data on observed driver phone use across Canada.

Data on cell phone use by drivers was collected as supplementary information during the observational seat belt use surveys carried out in rural areas of Canada in September 2006 and urban areas in the same week in September of 2007.

METHOD

The September 2006 and September 2007 surveys measured primarily the seat belt usage of all occupants and also cell phone use by drivers separately in rural Canada and urban Canada. Rural Canada includes towns with a population of fewer than 10,000 but more than 1,000 inhabitants that are located outside any census metropolitan area or census agglomeration1. Urban Canada includes communities with a population over 10,000, plus those communities with a population of less than 10,000 that are located within a census metropolitan area.

In the collection of data on cell phone use, the rural survey targeted the drivers of light-duty vehicles, which included passenger cars, light trucks, minivans and sport utility vehicles ( SUVs ). The survey, which occurred over the week of September 15 to 21, 2006, involved 249 sites. Each observation period was two hours long and took place during daylight hours (between 7:30 a.m. and 18:30 p.m.). A total of 41,137 vehicles and drivers were observed during the course of the survey.

The urban survey targeted the drivers of light-duty vehicles, which included passenger cars, light trucks, minivans and SUVs . This survey, which was conducted over the week of September 15 to 21, 2007, involved two separate observation periods at each of 270 sites. Each observation period was one hour long and took place during daylight hours (between 7:30 a.m. and 18:30 p.m.). A total of 92,440 vehicles and drivers were observed during the course of the study.

Therefore, during the two surveys, a total of 133,577 vehicles and drivers were observed at 519 sites across Canada.

RESULTS

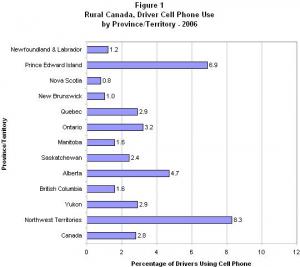

Driver Cell Phone Use by Jurisdiction

Figure 1 shows that an estimated 2.8% (± 0.2%) of drivers in rural communities were using a cell phone in 2006. Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Ontario, Alberta, the Yukon and the Northwest Territories were at or above the national average. Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia were below the national average. No data was collected in Nunavut in 2006.

Figure 2 shows that in 2007 an estimated 5.9% (± 0.4%) of drivers in urban communities were using a cell phone. Ontario and Alberta were at or above the national average. Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Yukon and the Northwest Territories were below the national average.

Figure 3 shows that an estimated 5.5% (± 0.3%) of drivers in Canada were using a cell phone. Ontario and Alberta were at or above the national average. Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Yukon and the Northwest Territories were below the national average. No data was collected in Nunavut in 2006.

CONCLUSION

Transport Canada recommends against using cell phones while driving. Drivers need to stay focused on the driving task. The use of cell phones, and other distractions, impairs the driver's ability to safely control their vehicle and effectively monitor and respond to events occurring in the road traffic environment. These events are often unpredictable; they could be anything from a changing traffic signal, to a sudden appearance of a pedestrian or bicyclist, to another vehicle stopping directly ahead. There is no “safe time' for distractions while driving.

Hand-held phone use by drivers was revealed, in this study, to be a common behaviour on Canadian roads, despite the risks and public concern. During the observation period, more than 1 in 10 drivers were observed using a phone in some urban communities. Rates of phone use would have been even higher if they could have also accounted for hands free phones.

The impact of this risky behaviour is likely to increase as wireless communications become even more common. The results of this study highlight the need for further countermeasures to reduce driver phone use. Newfoundland and Labrador banned hand-held phone use by drivers in 2003; Quebec and Nova Scotia followed in April 2008. Other provinces and territories are actively considering similar legislation.

Since historical data on cell phone use by drivers do not exist, any trends showing increased or decreased usage cannot be determined at this time. As the data are collected in future seat belt use surveys, trend lines will develop. The data presented above on cell phone use by drivers of light duty vehicles in 2006 and 2007 in Canada will become the foundation for comparison of future data. It could provide a baseline on which to evaluate the impact of legislative, and other, countermeasures.

REFERENCES

Harbluk, J.L., Noy, Y.I., & Eizenman, M. (2002). The impact of cognitive distraction on driver visual behaviour and vehicle control, report no. TP13889E. Transport Canada, Ontario.

Harbluk, J.L., Noy, Y.I., Trbovich, P.L. & Eizenman, M. (2007). An on-road assessment of cognitive distraction: Impacts on drivers' visual behavior and braking performance. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 39, 372-379.

Vanlaar, W., Simpson, HM, Mayhew, D. & Robertson, R. (2007). The Road Safety Monitor 2006: Distracted Driving. Ottawa: Traffic Injury Research Foundation available at: www.trafficinjuryresearch.com/publications

1To be more exact, the definition used in this survey also includes those communities that have a population over 10,000 but are not classified as census agglomerations in Statistics Canada 2001 census.