by Michael Schuster, Chief Instructor, Aviation Solutions

Windshear is quite simply rapidly changing wind. It could be horizontal (such as from a low-level jetstream) or vertical (such as from convective weather). The term windshear literally means a “tearing” of the wind as it changes abruptly.

However, what many pilots cannot easily define is how much tearing is required for windshear to be present. In the Flight Safety Foundation Approach and Landing Accident Reduction Toolkit, Briefing Note 5.4, windshear is defined as unexplained:

- Airspeed deviations of +/- 15 knots or more

- Vertical-speed excursions of 500 fpm or more

- Pitch attitude excursions of 5 degrees or more

- Glideslope deviations of 1 dot or more

- Heading variations of 10 degrees or more

- Unusual power requirements

- Groundspeed variations

The dangers of windshear are well known and the accident list regretfully long. One common theme across many windshear accidents is unfortunately that the crew did not recognize it early enough to carry out an effective recovery.

Recognizing windshear is a critical first step to recovering from it. From personal experience, I’ve seen many pilots be their own worst enemy and initially mask the windshear event. For example, a pilot may be so focused on flying their target approach speed that they may not notice they have adjusted their pitch attitude or vertical speed significantly in order maintain that airspeed. They may still have the target speed, but the vertical speed has come to zero and the pitch attitude has changed by more than five degrees and, in some cases, they have had to pull the power to idle to do so.

Another “gotcha” is heading variations: many pilots forget that windshear could come from a lateral position such as a thunderstorm cell located on the left or right; that’s why heading and groundspeed are in the above list as well. As you climb and descend, you can expect a normal amount of veering or backing of the wind. However, an abrupt change in direction or speed can be an early indicator of windshear. With so many of today’s aircraft equipped with advanced avionics and complete GPS packages, monitoring groundspeed should not be cumbersome.

When it comes to recovery, the general rule of thumb (barring any specific directive in the POH/AFM or company standard operating procedures) is to climb away from the ground at the best lift/drag ratio. For smaller aircraft, this is Vy, and for larger aircraft, V2 or Vga.

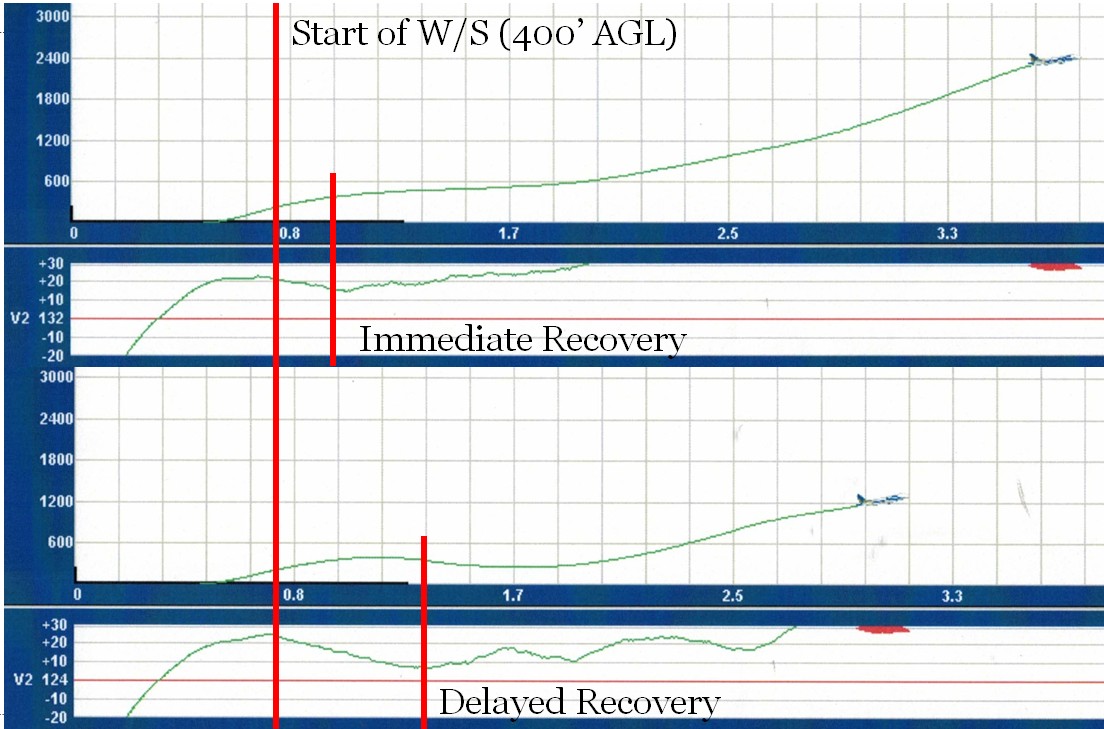

While flying at the correct escape airspeed is important, clearly understanding when you’ve entered windshear may be even more important. Below are two representative recovery profiles taken from a windshear encounter in a simulator.

In both cases, the performance decreasing shear started as the aircraft was climbing through 400 ft above ground level (AGL). In the first case, the pilot quickly recognized that the aircraft speed should not be decaying and initiated recovery immediately. In the second case, the pilot waited until speed had decayed to nearly V2 before initiating recovery—approximately ½ nautical miles (NM) later along the departure path.

It should be noted that the second pilot flew the recovery more effectively; they were much more accurate at maintaining the target speed of V2. However, the first pilot, even though they flew at V2 +20, didn’t get a sink during the manoeuvre like the second pilot did. Why? It may be worth considering the extra energy the aircraft was carrying when the recovery was initiated in Case 1.

Ultimately, both recognition and recovery skills are critical in any windshear encounter. But, as pilots, we may want to increase our focus on improving recognition skills.

A version of this article originally appeared on Aviation Solutions website. Mike Schuster is an experienced Class 1 flight instructor who has taught at all levels, from ab initio to airline. He is the Chief Instructor at Aviation Solutions, which is an authorized Flight Instructor Refresher Course provider for rating renewal.

Text Description

Windshear at 400’ AGL

in the first case, Immediate recovery, the pilot initiated recovery immediately, even though they flew at V2 +20, didn’t get a sink during the manoeuvre like the second pilot did.

In the second case delayed recovery, the pilot waited until speed had decayed to nearly V2 before initiating recovery—approximately ½ nautical miles (NM) later along the departure path.