by Joel Morley, Chief of Aviation Safety Analysis, Civil Aviation, Transport Canada

Background: A slow move from advisory to prescribed visibility

The International Civil Aviation Organization standards and recommended practices (ICAO SARPS) are established to ensure a uniform safety standard throughout the world. They stipulate that an instrument approach shall not be continued into the final approach segment unless the reported visibility is at or above the visibility specified on the instrument approach procedure (commonly referred to as the “charted visibility”).

In spite of this globally accepted ICAO standard, historically in Canada the published visibility associated with an instrument approach has only been advisory. Up to now, although there has been some movement towards the internationally accepted standard, this progress has been very slow.

This article describes:

- the increased level of risk that exists when approaches are conducted with less than the charted visibility;

- an analysis of accidents that occurred with less than the charted visibility and the critical human factors that are common to them; and

- how the new, simplified regulations will help improve safety during instrument approaches and align Canada with the global aviation community.

Overview of approach ban regulation development in Canada

Historically: Only runways serviced with a runway visual range (RVR) were subject to an approach ban. Approaches were permitted anytime RVR was greater than 1200 or was not provided.

2002: Following a number of accidents, the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) issued recommendation A02-01, calling on the Department of Transport to “expedite the approach ban regulations prohibiting pilots from conducting approaches in visibility conditions that are not adequate for the approach to be conducted safely.”

2006: Current approach ban regulations were published. Due to a series of compromises, the resulting approach ban regulations remained unchanged for general aviation and allowed commercial operators to perform approaches with 75% of the published advisory visibility or 50% if the company had been granted the required operations specification.

2017: Following a low visibility approach accident (A15H0002), Transport Canada Civil Aviation (TCCA) began re-examining the approach ban. A white paper was produced, recommending that TCCA take the necessary steps to implement prescribed visibility limits for instrument approaches.

2020: Responding to additional reduced visibility approach and landing accidents, the TSB issued recommendations A20-01 and A20-02, calling on the Department of Transport to review and simplify operating minima for approaches and to induce a mechanism to stop approaches that are not permitted by regulation.

2021: Transport Canada (TC) issued Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA) 2021-011, outlining the intent to move toward prescribed approach visibility limits

Being led down the garden path: How reduced visibility approaches increase risk

Given that the published approach visibility has been advisory for many years in Canada, it is reasonable to conclude that most of the approaches conducted in accordance with these regulations end successfully (with either a missed approach or an uneventful landing).

However, accidents continue to happen. In 2020, the TSB identified 18 approach and landing accidents where the reported visibility was less than that published on the approach chart. Significantly, these accidents took place during the 14 years following the introduction of the current approach ban regulations in 2006.

There is a clear pattern that emerges when one studies reduced visibility approaches that were unsuccessful. This pattern clearly demonstrates how these approaches carry an increased level of risk. This article will examine five of these accidents to illustrate this pattern.

Table 1 provides a summary of five low visibility landing accidents. In each case, the crew were aware of the threat presented by the weather. They had been monitoring it throughout the flight and had reviewed the missed approach procedure and plans for diversion to the alternate. However, in all cases, attempting the approach was permitted by the current regulations (or was believed to be permitted).

When faced with visibility below the advisory for the approach to be conducted but above the minimum required by the regulation, the flight crews were faced with an obvious choice. In these circumstances, crews will almost always conduct the approach and attempt to land.

Upon arriving at minimums, all the occurrence flight crews observed some visual cues. While these visual cues may have been enough to identify the runway environment, there may not have been enough visual cues to fully judge and control the aircraft’s trajectory towards the runway. At this point, decision-making required more judgement, since there are no clear criteria for what visual references are sufficient. In these occurrences, expecting the visual cues to improve as they get closer to the runway, each of these flight crews continued.

At some point in all these accidents, there was some disturbance to the flight path that required intervention by the flight crew. In several cases, the aircraft was above the ideal trajectory, in several cases, it was below, and in one case, a lateral deviation was introduced. In some cases, these deviations were noted, and attempts were made to correct, and in others, the crew were not aware of the deviation until it was too late.

The question often posed in relation to these occurrences (with the benefit of hindsight) is why, when faced with minimal visual cues and a disturbance to the flight path, did the crew not execute a missed approach in time to prevent an accident?

The answer is that during a period of high workload, where information is arriving piece-meal or is unclear and the task of landing the aircraft is almost complete, biases in information processing are at their strongest, and the available information is not sufficiently compelling to prompt a change of plan.

Information processing biases are a normal byproduct of the human ability to direct their limited attentional resources when operating in complex environments. Expectation bias and plan continuation bias help explain why the cues available in these occurrences were insufficient to prompt a timely go-around.

Expectation bias: When people expect one situation, they are less likely to notice cues indicating that the situation is not quite what it seems. Expectation bias is worsened when people are required to integrate new information that arrives piecemeal over time in incomplete, sometimes ambiguous, fragments.

Plan continuation bias: Once a plan has been made and implemented, cues indicating the plan is not working need to be more salient or compelling if they are to be recognized due to the natural tendency of our attentional processes to attend more to information that supports our current view. Plan continuation bias becomes even stronger when a task (e.g., a landing) is on the verge of being completed.

This combination of poor-quality visual cues and normal limitations in information processing make it more difficult to recognize the fact that these cues were insufficient to effectively judge the aircraft’s trajectory relative to the runway contributed to the very late detection of an undesired aircraft state. By the time the deviation was detected by the crew, the aircraft was close to the ground, in a low energy state with few visual cues from which to execute a missed approach. All five examples resulted in accidents including landing short, runway overruns, a lateral runway excursion and one loss of control.

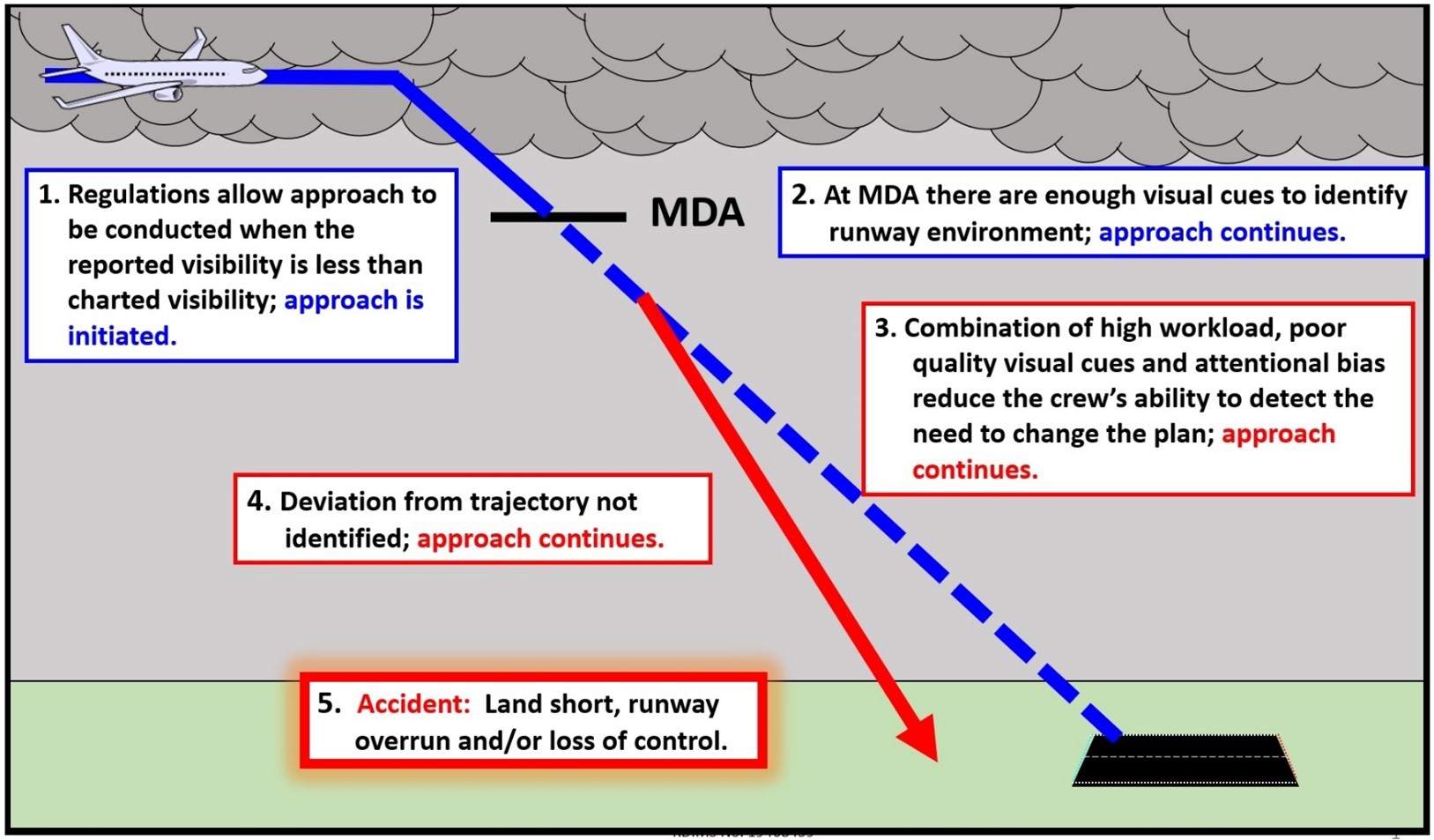

Anatomy of a reduced visibility landing accident.

Illustration by Joel Morley / Robert Kostecka

Anatomy of a reduced visibility landing accident - Text version

- Regulations allow approach to be conducted when the reported visibility is less than charted visibility; approach is initiated.

- At MDA there are enough visual cues to identify runway environment; approach continues.

- Combination of high workload, poor quality visual cues and attentional bias reduce the crew’s ability to detect the need to change the plan; approach continues.

- Deviation from trajectory not identified; approach continues.

- Accident: Land short, runway overrun and/or loss of control.

Being “led down the garden path” is a useful idiom to describe the sequence of events in these occurrences. In common usage, the phrase means to deceive or mislead someone. While the exact origins of the phrase are not known, it is often attributed to referring to “deceitful courtships or dalliances in pleasant and possibly secluded places.” In all of these occurrences, the crew were seduced by the presence of a few visual cues, whose aim was to lead them further down the approach and whose inadequacies were not recognized until it was too late.

How clear regulations will help

Bringing Canada’s regulations in line with international best practice by adopting a prescribed visibility limit for instrument approaches will serve to provide clear decision-making guidelines for crews. Approaches with a higher risk of placing crews in a situation with inadequate visual cues will no longer be permitted, and crews will have clear guidance to assist them in their decision-making.

Like the principle of establishing clear stabilized approach criteria to make sure that all involved explicitly understand when a missed approach is expected, prescribed visibility limits will serve to set clear expectations about when an approach, carrying increased risk and with limited probability of being successful, should not be attempted.

Table 1: A selection of reduced visibility occurrences

A97H0011: A CL-65 aircraft conducted a CAT 1 ILS approach to Runway 15 in Fredericton. The weather on arrival was reported visibility of mile in fog with an RVR of 1200. An approach was permitted under the regulations at the time. At minimums, the pilot monitoring called approach lights, and the pilot flying (PF) indicated they would continue with the landing. Shortly after autopilot disconnect, the aircraft began to deviate above the glidepath, and efforts to recover were unsuccessful. Upon reaching 35 ft, the captain assessed that the aircraft was not in a position to land safely and called for a go-around. During the go-around, the aircraft stalled aerodynamically and came to rest in the trees to the side of the runway. Nine passengers received serious injuries.

A05W0010: A DC-9 conducted a CAT 1 ILS approach and landed on Runway 34 in Calgary with a reported RVR of 1400. At minimums, the PF acquired the approach lights and elected to continue. A left roll was detected by the pilot monitoring shortly after auto-pilot disconnect, and the PF attempted to correct. The aircraft touched down left of the centre line, departed the runway and travelled 1 600 ft before climbing out on the missed approach procedure. While on the ground, an airport sign was struck damaging the aircraft’s landing gear. The aircraft returned to Calgary for a second ILS approach to the same runway and a successful landing. The TSB investigation found that with mile visibility in blowing snow, the available visual cues were inadequate to detect and correct the lateral deviation in the late stage of the approach and landing.

A08O0333: A DHC-8-100 conducted a localizer approach (ILS with glideslope inoperable) to Runway 08 in North Bay using a Standard Constant Descent Angle (SCDA) technique. The weather at the time was 100-ft ceiling with visibilities of to statute miles in light drizzle and mist. The advisory visibility for this approach is 1 SM, and the crew applied the company ops spec that allowed them to conduct the approach with SM visibility. The SCDA was initiated approximately 1 nautical mile after crossing the final approach fix. As a result, the vertical profile was above the desired approach profile, and the aircraft arrived at the missed approach point approximately 220 ft above the minimum descent altitude (MDA). The crew were not aware they were above the desired flight path or the distance to the runway. At or near the MDA, the crew saw a few runway edge lights and decided to continue the approach. The runway end lights were obscured by a windrow, and the crew had no good visual references to indicate the distance down the runway. The aircraft touched down with approximately 1 100 ft of runway remaining and shortly after touchdown, the approach lights for Runway 26 came into view. The aircraft ran off the end of the runway and stopped in 2 to 3 ft of snow. There were no injuries, and the aircraft sustained minor damage.

A15H0002: An A320 aircraft conducted a localizer approach to Runway 05 in Halifax. A snowstorm was taking place at the time, and the aircraft had entered a hold due to a reported visibility of SM in heavy snow. The crew were monitoring the situation and were preparing to divert to their alternate airport of Moncton. Upon receiving a special weather update reporting SM visibility in snow and drifting snow and a vertical visibility of 300 ft, the crew requested and were cleared for the approach. The company held an ops spec allowing an approach with 50% of the advisory visibility and, as such, the approach was now permitted. At minimums, the pilot monitoring (PM) called “lights only,” and the PF called “landing.” During the approach, the aircraft drifted below the required vertical profile, and this went undetected by the crew. On very short final, power lines came into view, and an attempt was made to climb. The aircraft struck the power lines and impacted the ground 740 ft short of the runway threshold. Overall, 25 people sustained injuries, and the aircraft was destroyed.

A18Q0030: A Beechcraft King Air A100 conducted a localized/distance measuring equipment (LOC/DME) approach to Runway 08 at Havre St. Pierre, Quebec landed 3 800 ft down the 4 500-ft runway and ran off the end. The reported visibility was SM in heavy snow and, although the approach ban regulations in place at the time would have required 75% of the advisory visibility of 1 SM for to conduct the approach, the captain believed the regulation did not apply to a weather report generated by an automated Weather Observing Station (AWOS). At minimums, the pilot monitoring called “minimums, no contact,” but the PF reported having contact and continued the approach. Crew coordination issues meant the aircraft was not configured for landing in a timely manner and, as a result, landing distance increased. Late on the approach, the crew acquired visual contact with a bare patch of pavement and attempted to align the aircraft with it. The PF lost awareness of distance over the runway and continued with the landing.

Table 2: Decision-making and information processing sequence in unsuccessful reduced visibility approaches

| Occurrence Approach Conducted Advisory Visibility | Reduced visibility approach permitted by regulations 1 1 | Some cues available at minimums–decision to continue 2 2 | Ability to detect flight path deviation after minimums limited 3 3 4 4 | Outcome 5 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

A97H0011 |

RVR 1200 met minimum for approach ban at the time ( mile visibility in fog). |

PM had approach lights. Continued. |

Aircraft deviated above glide path after autopilot disconnect. Captain called for go-around at 35 ft. |

Aircraft stalled aerodynamically during go-around. |

|

A05W0010 |

RVR 1400 met minimum for approach ban at the time (visibility to mile in blowing snow). |

Identified approach lights and continued. |

Left roll induced after autopilot disconnect. PM called deviation, PF correcting. |

Aircraft departed left side of runway after touchdown. Impacted airport signage. Go-around initiated and returned to land. |

|

A08O0333 |

Visibility variable between and SM. Crew applied company ops spec that allowed approach at SM. |

Crew had some of runway edge lights in view. Runway end lights obscured by windrow. Continued. |

Late initiation of descent and resulting trajectory above the desired vertical profile not recognized by the crew placing the aircraft close to the runway at MDA. Crew did not have runway end lights (obscured by windrow) or other visual cues to effectively assess position relative to runway length. |

Aircraft touched down 8 900 ft past the threshold of the 10 000-ft runway and ran off the end. |

|

A15H0002 |

Due to visibility of SM in heavy snow, crew held to wait for visibility to improve. Upon receiving report of SM (50% of advisory visibility as allowed by company ops spec) crew initiated the approach. |

Identified approach lights. |

Aircraft descended below desired descent profile. Not detected by crew until power lines came into view on very short final. |

Aircraft struck power lines and impacted the ground 740 ft short of the runway threshold. |

|

A18Q0030 |

AWOS reported visibility was SM in heavy snow. Although regulations in place required 75% of advisory visibility ( SM in this case), captain believed AWOS visibility was not limiting and believed approach was permitted. |

PM called “minimum, no contact.” PF indicated having visual contact and continued approach. |

Aircraft not configured for landing increasing landing distance. Crew had visual contact with bare patch of pavement and attempted to align aircraft. Distance down runway not recognized. |

Aircraft touched down 700 ft from the end of the runway and ran off the end. |

Joel Morley is the Chief of Aviation Safety Analysis for Transport Canada Civil Aviation. Prior to taking on this role, Joel served as a Human Factors Investigator with the Transportation Safety Board of Canada and as an Operational Safety and Human Factors Specialist with NAV CANADA. Joel completed his graduate education in Applied Psychology from Cranfield University in the UK.