by Robert Kostecka, Inspector, Flight Standards Division, Civil Aviation, Transport Canada

Over the years, there have been many accidents and incidents related to approaches and landings in reduced visibility conditions. The Transportation Safety Board (TSB) has rightly expressed concern that these incidents have persisted, even after the implementation of the current approach ban regulations.

Between December 2006 (the implementation date of the current regulations) and May 2020, the TSB identified 32 events that occurred following approaches conducted with inadequate visual references. Of these 32 incidents, 18 occurred during a landing in weather conditions where the reported visibility was below the charted visibility value published on the instrument approach procedure (IAP).

The analysis of the accidents and incidents that occurred in visibility that was less than the charted visibility clearly demonstrates that approaches in these conditions carry an increased level of risk. This is the fundamental issue that Transport Canada is striving to address through the approach ban safety initiative.

The analysis of accidents and incidents in visibility that was less than the charted visibility clearly demonstrates that approaches in these conditions carry an increased level of risk.

Credit: Transportation Safety Board of Canada

To better understand this important safety issue, as well as the necessary steps to address it, this article will outline:

- why adherence to the charted visibility is important to reducing risk;

- why the current situation in Canada needs to be addressed; and

- the solutions that are under development to address the identified safety issues.

Why adherence to charted visibility is important to reducing risk

The visibility that is published on an IAP serves a very important purpose. It specifies the minimum visibility at which pilots should have sufficient visual cues available to transition to flight by visual reference and successfully land the aircraft.

Pilots and operators need to understand the important purpose that charted visibility serves.

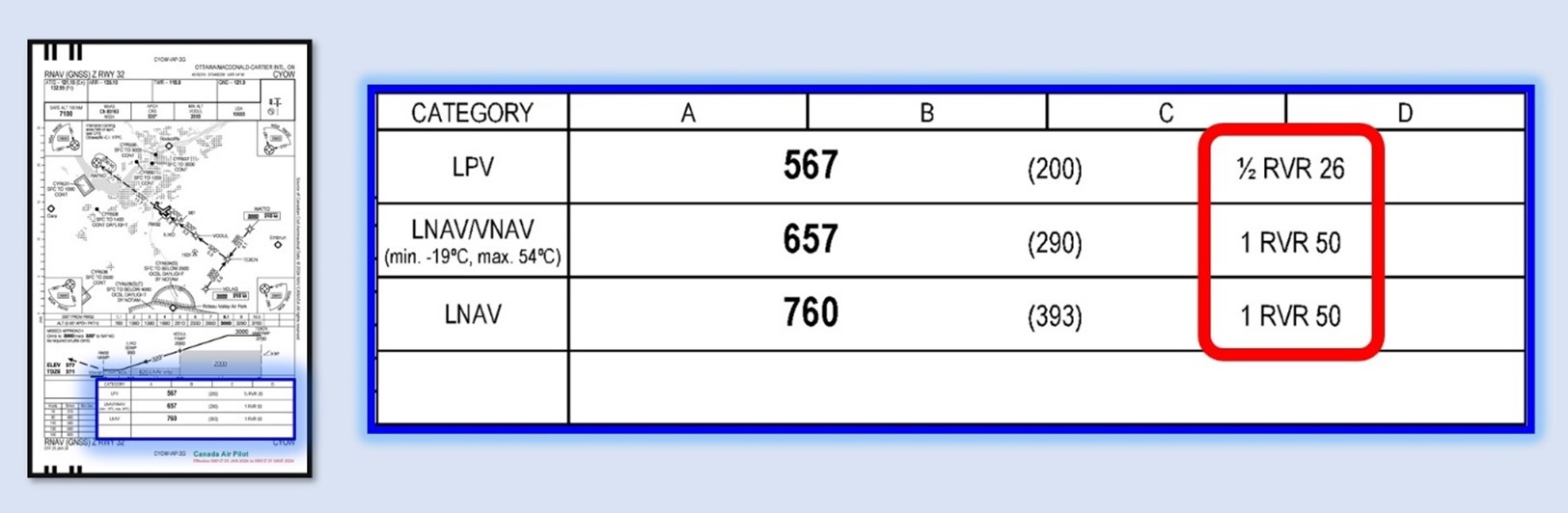

Example instrument approach procedure via NAV CANADA.

Not for navigation

When conducting an instrument approach, in order to continue the descent to a landing, the pilot must establish the required visual reference no later than the decision altitude (DA), decision height (DH) or minimum decision altitude (MDA). As the descent to landing continues, the pilot needs to have sufficient visibility to:

- assess the position of the aircraft relative to the runway;

- maintain control of the flight path both laterally and vertically;

- counter the effect of crosswind and prevent lateral drift;

- align the fuselage during the landing flare; and

- maintain directional control during the touchdown and rollout.

The charted visibility that appears on an IAP is the minimum visibility required to provide the pilot with sufficient visual cues to safely perform the critical tasks listed above, while continuing the descent (below DA, DH or MDA) to a landing.

The charted visibility is the minimum visibility required to provide the pilot with sufficient visual cues to safely continue the descent (below DA, DH or MDA) to a landing.

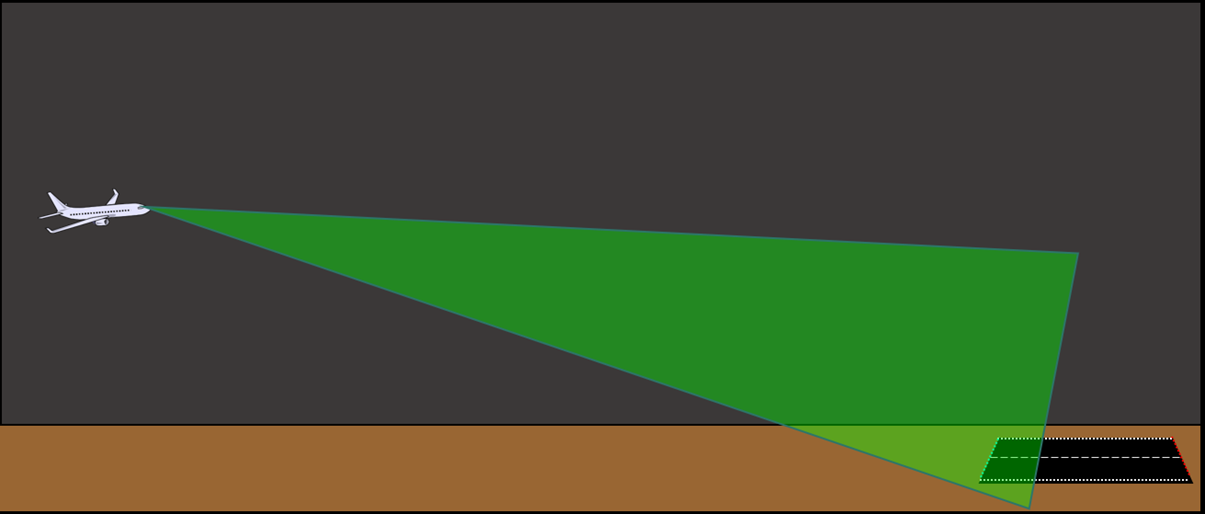

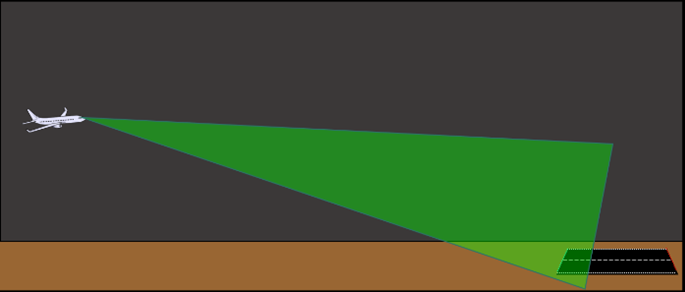

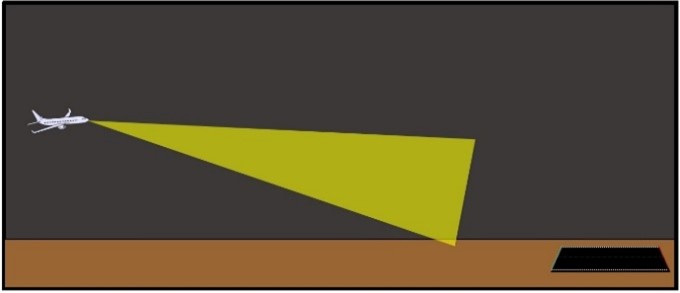

Illustration by Robert Kostecka

The charted visibility is established through requirements specified in TP 308–Criteria for the Development of Instrument Procedures. These requirements include such things as the approach type, DH or HAT and approach lighting, to name just a few.

Throughout the world—as per the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standard—the reported visibility must be equal to or greater than the charted visibility for an instrument approach to be continued into the final approach segment. Simply put, the required minimum visibility is the charted visibility.

In contrast, here in Canada, we currently consider the charted visibility as being merely “advisory visibility.” For the reasons described below, this needs to change.

Why the current situation in Canada needs to be addressed

At present, under the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), all air operators are permitted to conduct an instrument approach with 75% of the charted visibility, and those with specific approval can be authorized to conduct an instrument approach with as little as 50% of charted visibility. There is no requirement respecting charted visibility for air operators North of 60˚, unless runway visual range (RVR) is reported.

For general aviation, the approach ban specifies visibility as low as RVR A 1200 and RVR B 600. This means that general aviation pilots and operators have the same visibility requirements for instrument approaches as airline pilots conducting Category II approaches. It should be noted that this requirement is only applicable to those runways where RVR is installed, and general aviation pilots do not have the aircraft equipment, ground equipment or training that are necessary to conduct Category II operations.

In considering the current regulations, we need to remember that, in accordance with the approach design criteria, the charted visibility is the minimum visibility required to provide the pilot with sufficient visual cues to safely continue the descent (below DA, DH or MDA) to a landing. The current regulations are based on using some portion of the charted visibility (i.e., some portion of the minimum visibility dictated by the IAP design criteria).

How Canada’s current approach ban regulations stack up

CAR 700.10 allows any commercial operator to conduct approaches with 75% of charted visibility.

This is only 75% of the minimum visibility required to provide the pilot with sufficient visual cues to safely continue the descent (below DA, DH or MDA) to a landing.

CAR 703.41, 704.37 and 705.48 allow commercial operators with a specific approval to conduct approaches with 50% of the charted visibility.

This is only 50% of the minimum visibility required to provide the pilot with sufficient visual cues to safely continue the descent (below DA, DH or MDA) to a landing

CAR 700.10 stipulates that there is no approach visibility requirement North of 60˚, unless RVR is reported.

CAR 602.129 stipulates that for general aviation, there is no approach visibility requirement unless RVR is reported.

Illustrations by Robert Kostecka

The risks associated with conducting an approach in less than the charted visibility are effectively described in TSB Report A15H0002. This collision with terrain occurred on March 29, 2015 in Halifax, NS, when the reported visibility was 50% of the charted visibility. The report points to elements such as the flight crew’s expectations and plan continuation bias that are common to other accidents and incidents that have occurred during approaches with less than the charted visibility. These human factors are discussed in detail in Being Led Down the Garden Path: Understanding the Human Factors Contributing to Low Visibility Approach Accidents, which appears later in this issue.

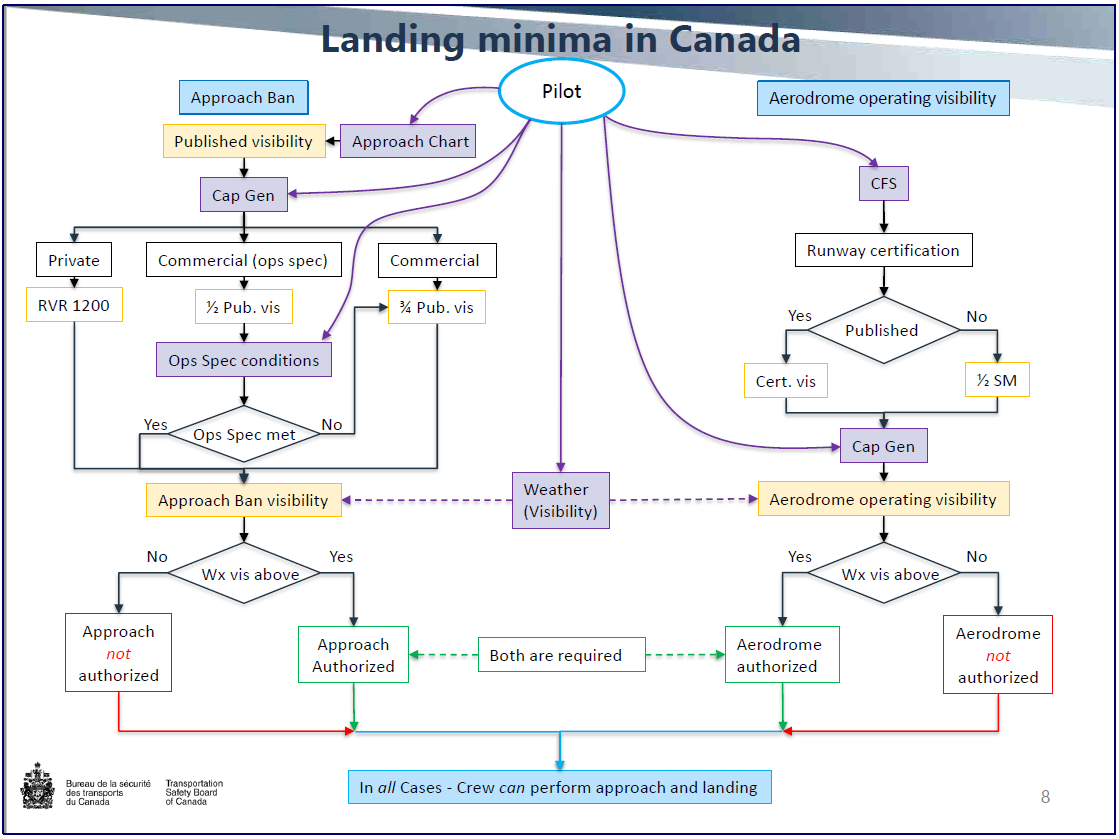

In a subsequent investigation of another accident that occurred when the reported visibility was less than the charted visibility (TSB Report A18Q0030), the TSB also commented on how complicated the current regulations and procedures for determining approach visibility are. The complex regulations governing whether a flight crew is permitted to conduct an approach is compounded by another complex set of requirements related to runway level of service; these requirements are used to determine whether the visibility is sufficient to operate on the aerodrome. In addition, the hierarchy of visibility reports used for runway level of service is also overly complicated and does not align with the hierarchy of visibility reports used in the approach ban regulations.

To illustrate the situation, the TSB produced a flowchart that depicts these two separate unaligned decision-making processes. This has informally been referred to as the “spaghetti diagram.”

The TSB used this diagram (Landing minima in Canada) to illustrate the complexity of the current regulations and associated procedures for determining if the visibility is suitable for conducting an approach.

Pilots find the current regulations to be overly complicated, confusing and a source of unnecessary workload and distraction during critical phases of flight. Several air operators have also expressed their safety concerns about the excessive complexity of our current regulations and have called for change.

In view of the current situation, the TSB made two key recommendations that require action:

- TSB Recommendation A20-01—Landing Minima in Canada:

- The Transportation Safety Board of Canada recommended that the Department of Transport review and simplify operating minima for approaches and landings at Canadian aerodromes.

- TSB Recommendation A20-02—Landing Minima in Canada:

- The Transportation Safety Board of Canada recommends that the Department of Transport introduce a mechanism to stop approaches and landings that are actually banned.

The solutions being developed to address the identified safety issues

Canada’s proposed regulationswould prescribe the visibility required to continue an instrument approach into the final approach segment in a simple and straightforward manner. Simply put, the reported visibility would need to be equal to or greater than the visibility published on the IAP.

To facilitate this change, IAP design criteria are being updated to ensure that the required visibility published for all instrument approaches will be greater than or equal to the runway level of service.

In addition, Transport Canada (TC) has conducted a comprehensive review of the processes for determining the required visibility for all phases of flight. During this review, numerous opportunities for improvement were identified; these would be addressed by simplifying and harmonizing the visibility report hierarchies for all phases of flight.

These changes are intended to eliminate the two separate decision-making processes that pilots currently have to determine the required visibility for the approach and landing. The alignment of visibility report hierarchies would also simplify the decision-making process for take-off.

TC is also developing regulations that would provide specific exceptions to the general rule. These proposed provisions are intended to provide operational flexibility while ensuring that the safety imperative is respected.

Transport Canada’s goal is one that is shared by all pilots and operators: advancing flight safety. Our proposed regulations are being designed to address the fundamental safety issues that have been identified. They are also intended to benefit pilots and operators by providing regulations that are easy to understand and easy to apply.

Robert Kostecka holds type ratings on a variety of Airbus and Boeing aircraft, as well as the DHC-8 and CRJ. His 13 000 hrs of flying time includes 4 000 hrs in command on large Transport Category jet aircraft. He has instructed on a wide variety of aircraft types and holds Category 1 Flight Instructor Rating. Robert’s experience at TC includes leading the development of flight operations guidance on wet and contaminated runways and serving on the international team that conducted the operational evaluation of the Airbus A380.