As part of the Oceans Protection Plan, we committed to “set tougher requirements on industry to provide quicker action for any spills from a ship.” To meet this commitment, we’re reviewing the regulations and standards that govern Canada’s oil spill response organizations.

This page is meant to prompt discussion about Canada’s oil spill preparedness and response, with a focus on how we certify industry response organizations. It is not final and does not reflect the final views of Transport Canada.

On this page

Introduction

After several high-profile oil spills, including the Nestucca in 1988 and Exxon Valdez in 1989, the Government of Canada commissioned the Public Review Panel on Tanker Safety and Marine Spills Response Capability. In 1990, the panel delivered a report on how to improve oil spill preparedness and response in Canada. There were two outcomes:

- Together with industry, we created the Ship-Source Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime

- Canada’s shipping and oil industries created 4 oil spill response organizations to prepare for and clean up oil spills caused by their vessels or oil-handling facilities

Canada is recognized as having strong oil spill preparedness and response but the requirements for response organizations were developed over 20 years ago. Since then, environmental response has evolved. It is time to review the standards and regulations so we can identify areas for improvement.

Background

About the regime

We created the Ship-Source Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime in 1995. It aims to fulfill Canada’s obligations under the International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation (OPRC).

States that are party to the OPRC Convention must have measures for dealing with pollution incidents, either nationally or in co-operation with other countries. This convention is part of a global system of agreements coordinated by the International Maritime Organization.

The Environmental Prevention and Response National Preparedness Plan outlines the roles and responsibilities for government and industry in Canada’s regime.

Who takes responsibility if a spill happens

In Canada we follow the “polluter pays principle,” which is supported by both industry and the government.

As set out in the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, the ship owner is liable for preventing and cleaning up pollution from ships. As well, under the Marine Liability Act, the owner of a ship is under strict liability to take financial responsibility, subject to specific exemptions, for reasonable measures to prevent, repair, remedy or minimize pollution damage by the ship. A polluter can meet their responsibilities through direct action or a third party such as a certified response organization.

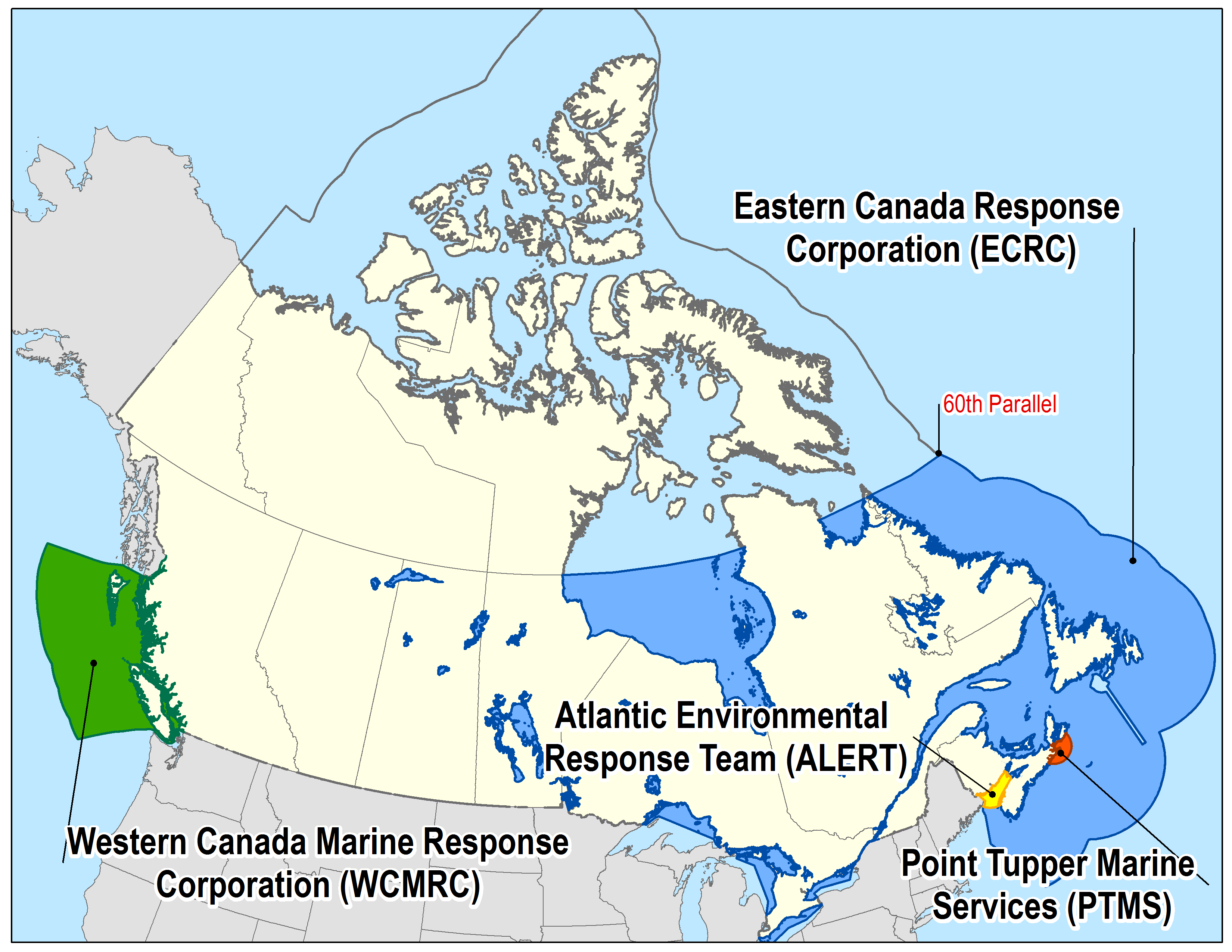

Four industry response organizations provide spill response capability across Canada (except in the Arctic). Industry created these organizations to make sure polluters minimize damage if a spill happens. Transport Canada oversees and certifies the response organizations every three years.

The Canadian Coast Guard is the lead federal agency for all ship-source spills in waters under Canadian jurisdiction. In the case of a spill, the Coast Guard advises the polluter of its responsibilities and, once satisfied with the polluter’s response plan, monitors the clean-up efforts.

However, if we can’t identify a polluter, or the polluter is unwilling or unable to respond, the Canadian Coast Guard manages the clean-up itself. In both cases, the Coast Guard ensures an appropriate response to the spill, working in a unified command until the incident is resolved. The Canadian Coast Guard works with:

- the polluter (when possible)

- federal, provincial and territorial agencies

- Indigenous Nations

- coastal communities and municipalities

Even when the Canadian Coast Guard manages the response, the ship’s owner remains liable for polluting under the Canada Shipping Act, 2001. The ship’s owner is also financially responsible under the Marine Liability Act for the spill, up to set amounts. In addition, affected parties can potentially seek compensation from two sources. They are:

- the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds

- Canada’s domestic Ship-Source Oil Pollution Fund

Environment and Climate Change Canada gives scientific and technical advice during an oil spill to ensure we do all we can to protect the environment. Fisheries and Oceans Canada also supports, along with other federal, provincial and territorial departments and agencies.

In the Arctic, the polluter pays principle and spill preparedness requirements for select vessels and oil-handling facilities are in effect but there are no response organizations. When a maritime oil spill happens, the polluter responds. If the polluter can’t or won’t take responsibility, the Canadian Coast Guard responds.

About the response organizations

Transport Canada certifies response organizations every 3 years. Through regulations and standards, we also set the level of preparedness that response organizations must maintain. This includes being able to respond to spills of up to 10,000 tonnes of oil within set times and operating environments.

To operate in Canada, prescribed vessels and certain oil-handling facilities must have an arrangement for oil spill response services with a certified response organization.

Prescribed vessels and oil-handling facilities include:

- oil tankers of 150& gross tonnage or more

- vessels of 400 gross tonnage or more that carry oil as cargo or as fuel

- groups of vessels that are towed or pushed, are of 150 gross tonnage or more in aggregate, and carry oil as cargo

- oil-handling facilities that received more than 100 tonnes of oil during the last 365 days

Funding

Prescribed oil-handling facilities and vessels pay an annual fee to response organizations. In addition, a fee is levied on vessels that carry oil in bulk. This bulk oil cargo fee is the largest source of capacity funding for response organizations. One response organization (Western Canada Marine Response Corporation) has also collected a capital asset/loan fee.

Response organizations use capacity funding to:

- maintain equipment stockpiles

- employ and train staff

- do exercises to prepare for oil spills

If an oil spill happens, response organization actions are funded by:

- the polluter

- the Government of Canada, if the polluter is unknown

Areas of response

The location of a response organization’s equipment and people is determined by the time standards in the Response Organization Standards. These standards use several terms we reference on this page, including:

- Geographic area of response—the overall portion of Canadian waters in which a response organization offers their services

- For example, Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC) serves the entire west coast

- Designated port—the location where a response organization must keep equipment and resources in order to meet time standards

- Primary area of response—usually the Canadian waters within a 50 nautical mile radius of a designated port

- Enhanced response area—a part of Canadian waters in which stricter time standards apply

- Unlike a primary area of response, the enhanced response area isn’t centered on a designated port

As an example, for illustrative purposes, this map shows areas of response for the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation.

The following map shows geographic areas of response for Canada’s 4 response organizations.

For discussion: response organization requirements

We are seeking input from across Canada to help improve how we regulate oil spill response organizations. Here are key areas to inform the discussion.

Recognizing local conditions and risks

The current Response Organization Standards are “one-size-fits-all” as response capacity requirements are the same across Canada, no matter the types and sizes of vessels that travel through an area.

Each response organization is required to maintain 150 tonnes of capacity in a designated port and also be able to deliver:

- 2,500 tonnes of capacity in each of their primary areas of response

- 10,000 tonnes of capacity for their geographic area of response

By defining primary areas of response around ports with major oil-handling facilities, the standards also emphasize being prepared for large crude oil spills. This approach made sense following major tanker spills in the 1970s and 1980s. But it is less relevant today. Non-tanker vessels have caused most oil spills in Canadian waters since 1995.

The standards aren’t very flexible. They don’t reflect regional differences or account for new shipping routes or increased vessel traffic. For example, in the port of Prince Rupert in Northern B.C., cargo vessels often carry bunker fuel in excess of 10,000 tonnes. Prince Rupert isn’t a designated port, so the response organization is not required to maintain equipment locally.

Key question:

- How could the requirements for response organizations be made more flexible, so they are based on local conditions and risks?

Strengthening response times and capacity

The Response Organization Standards tell us how quickly response organizations should respond to oil spills of different sizes.

These time standards emphasize using significant resources for large spills of persistent oil products near a designated port. However, since the standards were created:

- Most spills have been small volumes of oil

- A number of high-profile spills have happened outside a primary area of response or enhanced response area

The public expects that a response to an oil spill will be immediate and measured in hours, not days. People question whether the current time standards are adequate.

Current response times set out how long a response organization can take to respond to spills in:

- a designated port

- a primary area of response or enhanced response area

- their geographic area of response

We created response times for 4 tiers of spills. They are outlined in the table below. Times reflect how quickly a response organization should be able to deliver equipment to a spill site.

| Tier 1

150 tonnes |

Tier 2

1,000 tonnes |

Tier 3

2,500 tonnes |

Tier 4 10,000 tonnes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designated port | 6 hours | 12 hours | 18 hours | 72 hours |

| Inside primary area of response | 18 hours | 18 hours | 18 hours | 72 hours |

| Inside enhanced response area | 18 hours | 18 hours | 18 hours | 72 hours |

| Inside the geographic area of response, but outside the primary area of response or enhanced response area | 18 hours + travel time | 18 hours + travel time | 18 hours + travel time | 72 hours + travel time |

The standard is similar for spills that happen within a response organization’s geographic area of response, but outside a primary area of response or enhanced response area. However, it allows more time based on travel. For example, for a spill of 2,500 tonnes, the response organization has 18 hours plus the time it takes to travel to the site. We base travel time on equipment being transported at 6 knots by sea, 65 km per hour by land and 100 knots by air.

Key question:

- How can we improve time standards for oil spill response?

Planning for cascading resources

Large oil spills likely need resources beyond one port or area. This is a guiding principle in oil spill response. Cleaning up a large spill may require resources from across a country, or even from multiple countries.

Cooperation between jurisdictions is written in the international convention for oil spill response. This concept is called “cascading resources.”

Canada’s current standards for response organizations don’t mention cascading resources. Instead they focus on the resources each response organization needs to have within their geographic and primary areas of response.

Key question:

- How could the certification process include the concept, that for large oil spills, the resources of multiple Canadian response organizations and/or international sources would be used?

Improving the certification process

In their 2013 report, the Tanker Safety Expert Panel said that “transparency [is] an important opportunity to engage the public and other local stakeholders in the planning process and in the continual improvement of the regime.”

Transport Canada reviews response organization plans every 3 years. The certification requirements for response organizations are outlined in the:

If a response plan meets these requirements, we re-certify the response organization.

The Response Organization Standards are fully available to the public. However, we also use guidance documents to help us interpret the requirements for response organizations that aren’t publicly available. Most important are the 1994 Final Standards for Response Organizations. These documents, including the 1994 Final Standards, aren’t mentioned in either the standard or regulations.

Response organization plans are not available to the public. As a result, stakeholders can’t review the level of preparedness established for a particular area.

Key question:

- How could the certification process for response organizations be more transparent?

Improving public awareness and participation

Response organizations are an important part of Canada’s system for environmental response. Yet many Canadians aren’t fully aware of how response organizations work, or about the challenges of oil spill response.

We want to build relationships between Indigenous groups, local communities and industry that goes beyond sharing information. Response organizations are hosting town hall meetings, doing community training, and offering awareness sessions. But there are still ways we can improve awareness and participation in oil spill preparedness and response.

Key questions:

- How can we improve public awareness about response organizations and oil spill response operations?

- As a member of an Indigenous group, or local coastal community, how would you like response organizations to involve you in their preparedness for oil spills?

Tell us what you think

We want your feedback on the current Ship-Source Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime.

If you would like to provide comments on anything you read here, or other issues related to oil spill preparedness and response, please send them to:

Email: TC.OPPRegResponsePlanning-PPOPlanreginterventions.TC@tc.gc.ca