Final Report of The National Supply Chain Task Force 2022

Letter to the Honourable Minister of Transport

Dear Minister,

The National Supply Chain Task Force is honoured to submit to you our final report, which embodies our urgent call to address Canada's transportation supply chain crisis. This report is the product of extensive consultations and engagements with a broad range of transportation organizations, stakeholders and industry experts across the country. Organizations and departments in the United States, Canada's largest trading partner, were also consulted to understand their perspectives on how to strengthen the North American supply chain.

A recurring theme in the report is the struggle of both government and industry to cope with uncertainties arising due to critical factors such as rapidly changing trade patterns, human and climate-caused disruptions, shifting geopolitical risk, and increased consolidation in major transportation modes. As a medium-sized player in the global market, Canada is finding it difficult to overcome these challenges, which have exposed and exacerbated longstanding weaknesses in the Canadian transportation supply chain.

To position Canada as a strong competitor in the global market and strengthen our economy, it is imperative that the Government of Canada join forces with industry stakeholders to address the transportation supply chain crisis. This report recommends taking a national approach to doing so, encouraging governments and private sector stakeholders to collaborate in building digital data hubs that will help improve our understanding of the intricate transportation network, which in turn will enhance planning and real-time decision making.

It further recommends that Canada's regulatory framework be modernized to reflect the future needs of an evolving transportation system.

Additionally, the report includes a series of specific short and long-term action items to help address operational shifts, service reliability and resilience, labour shortages, capacity constraints, infrastructure, supply chain visibility, regulatory certainty, and shifts in governance.

It has been a privilege for the Task Force to serve Canada, especially at a time when action, collaboration and transformation are so desperately needed. We owe thanks to all those who took the time to present their views, send their submissions and participate in various discussion platforms. Without them this report would not have been possible.

Submitted respectfully,

The National Supply Chain Task Force

Co-Chair

Co-Chair

Contents

- 2. Executive summary

- 5. Introduction

- 12. Establishing the National Supply Chain Task Force

- 16. Recommendations

- 36. Annex A – National Supply Chain Task Force: Mandate

- 42. Annex B – Brief Summary of Industry Perspectives

- 50. Annex C – Stakeholder Engagement List

- 56. Annex D – A Word of Acknowledgement

Executive summary

Action. Collaboration. Transformation. These three words embody both the spirit of the recommendations contained in this report and our call to action to government, transportation supply chain stakeholders and all Canadians to address the transportation supply chain crisis.

Canada is a medium-sized player in a global market currently wrestling with numerous factors that are contributing to high levels of uncertainty: rapidly changing trade patterns, human and climate-caused transportation supply chain disruptions, shifting geopolitical risk, increased consolidation in major transportation modes, and many more. Both industry and government have struggled to cope with these near-term difficulties, which have also exposed and exacerbated several longstanding structural and systemic weaknesses in Canada's transportation supply chain. As such, government, transportation and logistics providers, shippers, producers, manufactures and retailers must act decisively and urgently together to create a supply chain system that is more agile, flexible, resilient, competitive and efficient than it is today.

Collaborative action is the key to transformation

Building such a system will require a national approach, with collaboration playing a central role. The economic deregulation of transportation policies over the past 30 years successfully unleashed the power of competitive, market-based forces across the sector (for example, the establishment of arms-length port and airport authorities to operate federally owned national ports and airports on a commercially autonomous basis). Today, Canada's transportation supply chain is a network of independently operated yet inter-related (and often inter-reliant) port and airport authorities along with countless transportation supply chain businesses that are privately held and, in some cases, publicly traded. Each has its own performance requirements and objectives, resulting in a fragmented and siloed approach. While some small, isolated efforts are being made to synchronize operations, generally each of the transportation modes (rail, trucking, marine and air) and Canada's port terminals, transload facilities, warehouses, shippers, receivers, exporters and importers all seek to optimize their own operations without considering their impacts on others in the supply chain.

Act

See page 34 and 35 for the Summary Tables and Recommended Timeline to Complete all Actions

With that context in mind, all government and private sector stakeholders in the transportation supply chain must redirect their energies to building digital data hubs that will allow for planning, real-time decision-making and an innate understanding of how each part of the chain is operating. Modernized and future-proof regulatory frameworks, along with intensified cooperation between and within the public and private sectors, will be needed if Canada is to remain relevant in the global marketplace.

The economic impact of Canada's transportation supply chain

That kind of transformation is vital given that Canada's transportation supply chain has both direct and indirect impacts on the prosperity and quality of life of all Canadians. International trade has contributed to more than half the value of Canada's gross domestic product (GDP) every year since 1992, peaking at more than 80% in 2000. In 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 supply chain shutdowns, trade still accounted for 61% of Canada's GDP. In 2021, Canada's international merchandise trade amounted to approximately $1.24 trillion, a 16.8% increase from 2020 — and the highest annual value of total trade on record. In 2021 the U.S., Canada's top trading partner, accounted for $774 billion ($476 billion exported, $298 billion imported), in total trade, comprising 62% of all Canadian trade that year.Footnote 1 This trade would not occur without the backbone of the transportation supply chain.

Canada's trading opportunity has never been so great. The world wants and needs Canadian natural resources and products, including critical minerals, potash, energy and grains. But we can capitalize on that opportunity only if those resources and products can be delivered competitively, efficiently and reliably. As Canada's trade volumes continue to increase, investment in critical infrastructure assets such as seaports, railways, highways and roads, and airports must also increase to meet demand. Furthermore, we must “sweat” these assets in every way possible, including through operational innovation. Building new infrastructure is only part of the solution. Data and visibility can also unlock capacity.

Our recommendations

Of course, creating a connected, resilient and efficient system is not a simple proposition. It goes beyond the practicalities of establishing critical gateways and corridors, identifying pinch points, and planning for and financing physical infrastructure for surge capacity or redundancy. It requires all stakeholders to work collectively and singularly toward the goal of organizing and adapting a transportation supply chain that functions in the national public interest: one that is operated for the common good of the country to ensure the general welfare, safety, security and well-being of Canadians.

To that end, the National Supply Chain Task Force offers eight long-term strategic recommendations along with a number of immediate and urgent actions that each fall into one of the Action, Collaboration and Transformation streams:

|

Action |

Collaboration |

Transformation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The time for bold action is now. The time for intense collaboration is now. The time for generational transformation is now. Let us begin.

Introduction

Canada's transportation supply chainFootnote 2 is nearing its breaking point. The major disruptions seen over the last two years have brought to light longstanding and newly emerging issues that must be addressed now — before our country's reputation as a reliable trading partner is further tarnished, as we heard from stakeholders and U.S. trading partners. Wild swings in supply and demand due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as climate shocks (e.g., wildfires, floods) and growing geopolitical uncertainty, have put trade norms and flows at risk. These challenges come at a time when Canada's natural resources, such as critical minerals, potash, energy and grains, are in high demand globally. But the only way to capitalize on that opportunity is to act now to ensure we can transport them to market competitively, efficiently and reliably.

The impacts of the last two years have also exposed the system's limited redundancy and resiliency, making it essential to take action immediately. Investment and planning at a national level are required to ensure Canada's transportation supply chain can withstand shocks and adjust to fluctuating demands and global trade dynamics. This transformation requires unprecedented collaboration and enhanced cooperation between the public and private sectors, as well as within the private sector itself. All players must mobilize, innovate and address gaps, and prioritize the building of efficiencies into the national transportation supply chain so it operates successfully for everyone.

Why Canada needs a resilient transportation supply chain

Canada's transportation supply chain is a key cornerstone of our economy that directly and indirectly impacts our prosperity and quality of life. The transport sector alone comprised 3.6% ($72 billion) of Canada's total real GDP in 2021,Footnote 3 and had a total industry output of $151.3 billion in 2019,Footnote 4 just prior to the onset of the global pandemic. In 2020, the sector directly employed 539,100 people (down from more than 631,650 people in 2019), accounting for 3.4% of Canada's workforce.Footnote 5

Broader impacts that the sector brings to our economy include the following:

- In 2019 the sector indirectly contributed $11.2 billion to Canada's GDP, and indirectly boosted employment by 103,349 jobs.Footnote 6

- International trade has contributed to more than half the value of our GDP every year since 1992, peaking at more than 80% in 2000.

- At the height of supply chain shutdowns in 2021 due to COVID-19, trade accounted for 61% of the country's GDP, and international merchandise trade amounted to approximately $1.24 trillion — a 16.8% increase from 2020, and the highest annual value of total trade on record.

- The U.S. is our top trading partner and accounted for $774 billion in total trade ($476 billion exported, $298 billion imported) last year, comprising 62% of all Canadian trade in 2021.Footnote 7

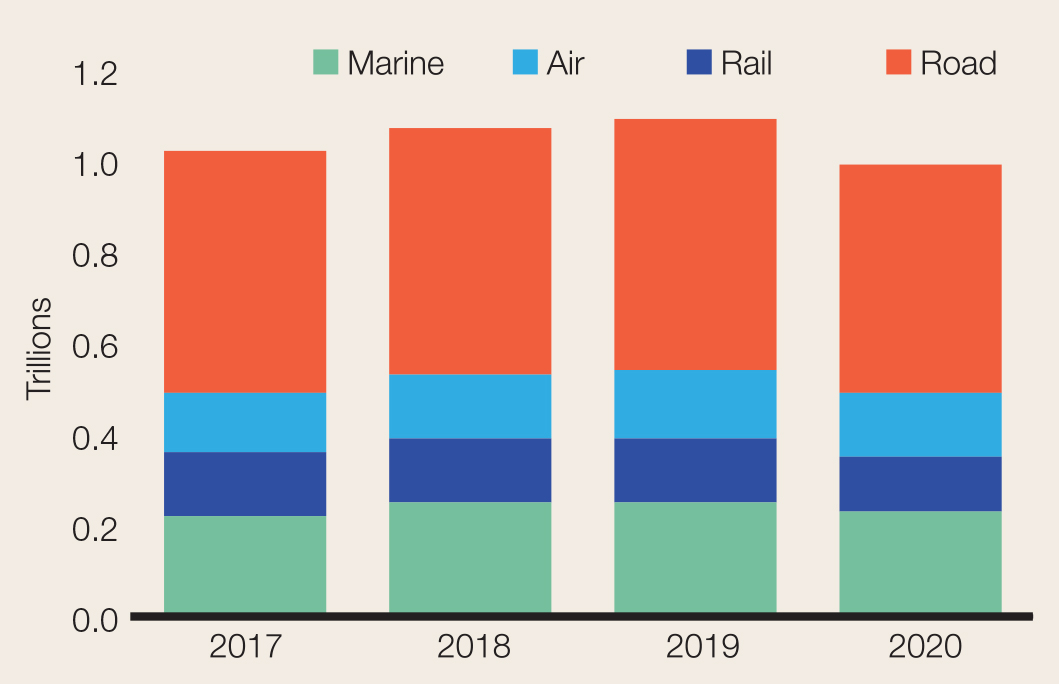

- In 2020, road transport accounted for 50% of Canada's merchandise trade (imports and exports combined), 23% moved by water, 15% by air, and 12% by rail.Footnote 8

Fundamentally, Canada's standard of living is directly connected to our success in international trade and, therefore, to our transportation system's performance. This includes our ability to get goods to and from international markets as well as our ability to ensure we receive the commodities, goods and essential supplies we need to thrive.

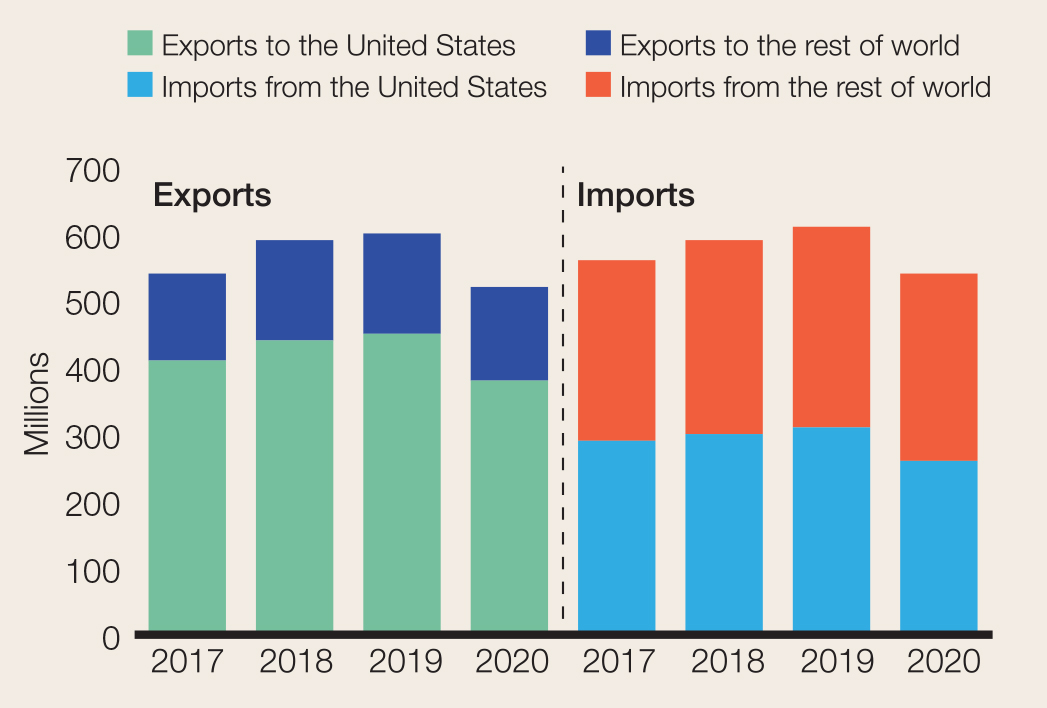

Figure 1: Import origins are more diversified than exports, where the U.S. dominates

(Export destination and imports origin by value, the U.S. in contrast with the rest of the world)

Source: Statistics Canada; Table 23-10-0269-01

Text description

|

Year |

Exports to the U.S. |

Exports to the Rest of the World |

Imports from the U.S. |

Imports from the Rest of the World |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2017 |

$414.2 billion |

$131.9 billion |

$288.9 billion |

$273.2 billion |

|

2018 |

$437.8 billion |

$146.4 billion |

$304.6 billion |

$291.3 billion |

|

2019 |

$446.1 billion |

$146.0 billion |

$305.3 billion |

$296.7 billion |

|

2020 |

$383.0 billion |

$139.8 billion |

$265.2 billion |

$277.9 billion |

Figure 2: Road is most common mode of transport for international trade

(Sum of merchandise trade, imports and exports value, by mode of transport)

Source: Statistics Canada; Table 23-10-0269-01, Note "Other" modes of transport are excluded.

Text description

|

Year |

Marine |

Rail |

Air |

Road |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2017 |

$218.2 billion |

$136.2 billion |

$130.6 billion |

$526.0 billion |

|

2018 |

$251.5 billion |

$143.4 billion |

$139.0 billion |

$540.0 billion |

|

2019 |

$247.3 billion |

$140.6 billion |

$149.4 billion |

$550.0 billion |

|

2020 |

$225.1 billion |

$115.4 billion |

$144.6 billion |

$502.0 billion |

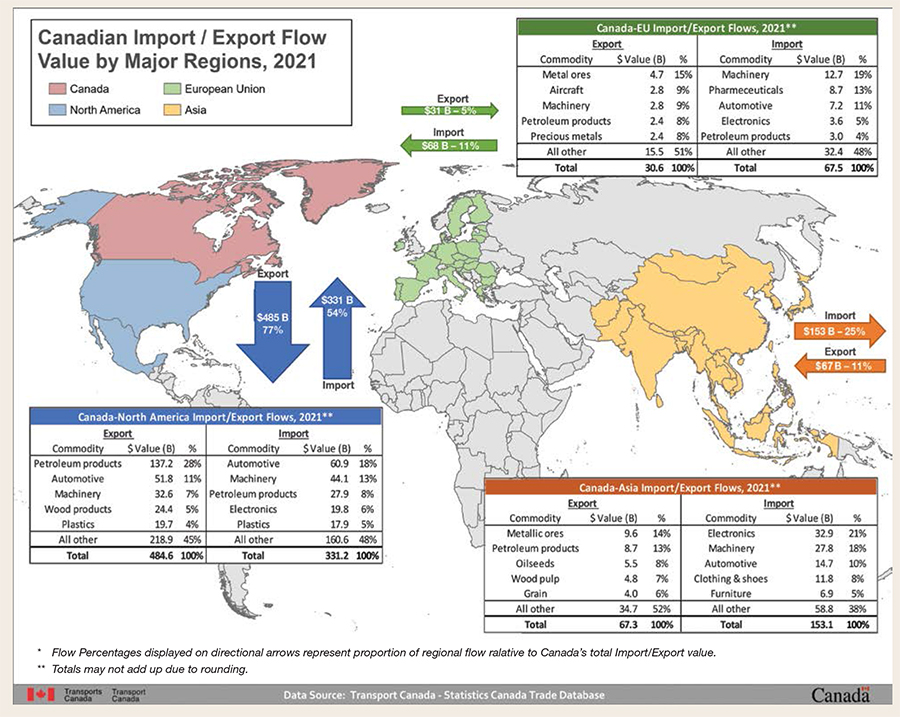

Figure 3: Wide variation in Canada's import/export trade flow composition

Source: Transport Canada – Statistics Canada Trade Database

Text description

|

Exports |

Imports |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Commodity |

$ Value (billion) |

% |

Commodity |

$ Value (billion) |

% |

|

Petroleum Products |

137.2 |

28% |

Automotive |

60.9 |

18% |

|

Automotive |

51.8 |

11% |

Machinery |

44.1 |

13% |

|

Machinery |

32.6 |

7% |

Petroleum Products |

27.9 |

8% |

|

Wood Products |

24.4 |

5% |

Electronics |

19.8 |

6% |

|

Plastics |

19.7 |

4% |

Plastics |

17.9 |

5% |

|

All Other |

218.9 |

45% |

All Other |

160.6 |

48% |

|

Total |

484.6 |

100% |

Total |

331.2 |

100% |

|

Exports |

Imports |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Commodity |

$ Value (billion) |

% |

Commodity |

$ Value (billion) |

% |

|

Metal Ores |

4.7 |

15% |

Machinery |

12.7 |

19% |

|

Aircraft |

2.8 |

9% |

Pharmaceuticals |

8.7 |

13% |

|

Machinery |

2.8 |

9% |

Automotive |

7.2 |

11% |

|

Petroleum Products |

2.4 |

8% |

Electronics |

3.6 |

5% |

|

Precious Metals |

2.4 |

8% |

Petroleum Products |

3.0 |

4% |

|

All Other |

15.5 |

51% |

All Other |

32.4 |

48% |

|

Total |

30.6 |

100% |

Total |

67.5 |

100% |

|

Exports |

Imports |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Commodity |

$ Value (billion) |

% |

Commodity |

$ Value (billion) |

% |

|

Metallic Ores |

9.6 |

14% |

Electronics |

32.9 |

21% |

|

Petroleum Products |

8.7 |

13% |

Machinery |

27.8 |

18% |

|

Oilseeds |

5.5 |

8% |

Automotive |

14.7 |

10% |

|

Wood Pulp |

4.8 |

7% |

Clothing & Shoes |

11.8 |

8% |

|

Grain |

4.0 |

6% |

Furniture |

6.9 |

5% |

|

All Other |

34.7 |

52% |

All Other |

58.8 |

38% |

|

Total |

67.3 |

100% |

Total |

153.1 |

100% |

Investment in Canada's transportation infrastructure by both the public and private sector is critical to the movement of goods in the transportation supply chain. Since the 1980s, the ratio of infrastructure investment to trade volumes has been steadily declining. While Canada's trade volumes have increased, investments in infrastructure have not kept up — and the transportation supply chain is reaching its limits. The current state of the transportation supply chain demonstrates that for the economy to continue to grow, simply maintaining the existing infrastructure is not sufficient. Both the public and private sectors need to increase investment in marine, road, rail and air transportation assets to facilitate economic growth. AnalysisFootnote 9 estimates that over the 50-year period from 2020 to 2070, investments of $4.4 trillion (or approximately $88 billion per year) in marine and transportation infrastructureFootnote 10 will be required to meet projected growth in population (assuming a 0.7% compound annual growth rate) and in GDP (assuming a 2.1% compound annual growth rate). The majority of this needed investment is in highway and road structures and networks ($3.3 trillion), railways ($284 billion), and seaports ($110 billion).

This estimate is based on historical trends and does not consider current commitments by public or private sectors entities,Footnote 11 nor does it consider increased investment that may be required to achieve more ambitious growth targets and response to significant, evolving challenges such as climate change and the dynamic supply chain context described in the following section. In our view, this is a conservative estimate of the total investment that will be required.

This investment is not to be borne by taxpayers alone. Major transportation supply chain infrastructure assets such as railways and ports are owned and operated by the private sector which must invest alongside government to meet trade demand and growth.

The forces behind the disruptions

Like many sectors, transportation has undergone many changes since the beginning of the 21st century, with the digital revolution transforming the traditional drivers of growth in the global economy. The sector has also faced several unique challenges related to congestion, traffic growth and shifts resulting from changing global trade patterns, and investment and financial pressures.

With the acceleration of these shifts in the last two years, our transportation supply chain has been operating in an increasingly uncertain and volatile environment. While the burden has eased since the height of the pandemic-induced congestion, bottlenecks remain prevalent and continue to affect our reputation as a preferred and trusted trading partner.

The pandemic-driven supply chain pressures were further exacerbated in 2021 by rising energy prices and transport disruptions (e.g., blockage of the Suez Canal, shortage of empty containers, port congestion, and overfull warehousing space). This constrained supply in key areas such as food and industrial inputs. Trade flows also became more unpredictable and uncertain due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Following this and the subsequent rebalancing of global trade patterns, the World Trade Organization (WTO) downgraded its expectations for growth of merchandise trade volumes from 4.7% to 3% in 2022.Footnote 12

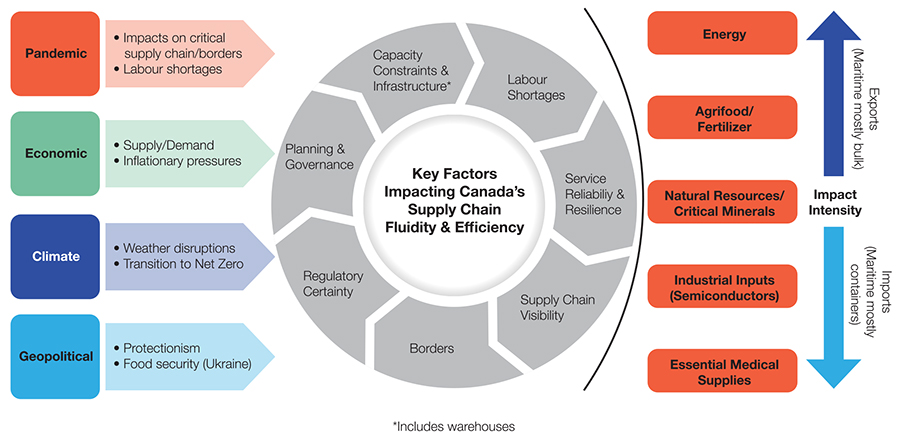

Figure 4: National Supply Chain task force—Diagnostic framework

Text description

Far left column lists four global drivers:

- Pandemic

- Impacts on critical supply chains and borders

- Labour shortages

- Economic

- Supply/Demand

- Inflationary pressures

- Climate

- Weather disruptions

- Transition to Net Zero

- Geopolitical

- Protectionism

- Food Security (Ukraine)

Middle section lists seven key factors impacting Canada's Supply Chain Fluidity and Efficiency that are all connected to one another in a circular manner

Key Factors:

- Capacity Constraints & Infrastructure (includes warehouses)

- Labour Shortages

- Service Reliability and Resilience

- Supply Chain Visibility

- Borders

- Regulatory Certainty

- Planning and Governance

Far right column lists trade priorities and their respective impact intensities on the transportation system:

The following commodities are mostly exported via the maritime sector in high volume, low value bulk shipments

- Energy transported largely by rail and marine modes

- Agrifood and fertilizer transported by truck, rail, marine modes

- Natural Resources and Critical Minerals transported by truck, rail, marine modes

The following goods are mostly imported via the maritime sector in containers, with higher value, time sensitive items shipped by air:

- Some Critical Minerals largely by truck, rail and marine modes

- Industrial inputs and Semiconductors by truck, marine and air modes

- Essential Medical Supplies by air mode

A number of global drivers are causing reverberating disruptions and longer-term impacts to traditionally stable global supply chains. Volatility has increased dramatically in key global and domestic industries since the pandemic. Climate change also continues to intensify, and extreme weather events are happening more frequently, further increasing the risk of disruptions to the transportation supply chain — and the corresponding financial and economic impacts across Canada.

Key factors contributing to Canada's supply chain fluidity and efficiency are wide-ranging yet highly interconnected. Bottlenecks or disruptions to one link affect the entire supply chain, meaning local pressures lead to national repercussions. The solutions needed to address these concerns throughout the supply chain must be creative and cooperative.

Canada's trade priorities as indicated in this framework illustrate our dynamic export/import scale. Major Canadian exports of high-volume bulk commodities (such as energy, agriculture, and key natural resources) depend heavily on rail to get to port and loaded onto ships destined for international markets, or on road transport for transborder trade. Higher value, time sensitive and often imported goods (e.g., specialized industrial components, pharmaceuticals) move by air. Disruptions to the transportation of any of these major commodities are prime examples of what can go wrong within Canada's transportation supply chain.

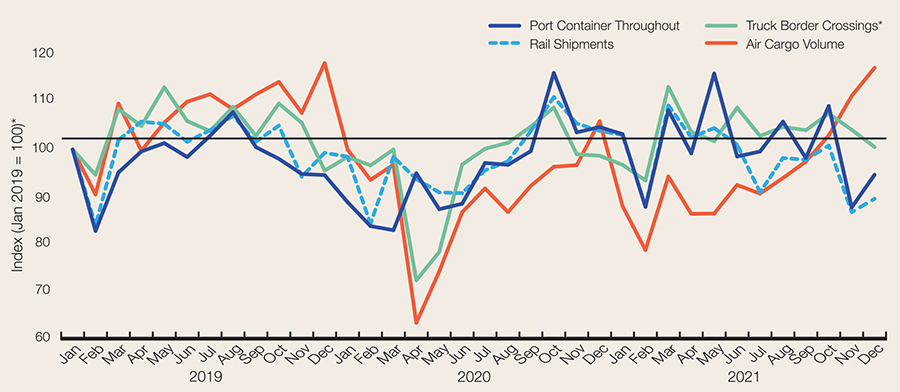

Figure 5: Freight flow by mode

Source: Statistics Canada, Transport Canada, Canadian Port Authorities

Text description

|

Year |

Port Container Throughput |

Rail Shipments |

Truck Border Crossings |

Air Cargo Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Jan 2019 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

|

Feb |

82.79 |

83.92 |

94.65 |

90.50 |

|

Mar |

95.14 |

101.98 |

108.51 |

109.67 |

|

Apr |

99.59 |

105.89 |

104.97 |

99.75 |

|

May |

101.33 |

105.40 |

113.13 |

105.68 |

|

Jun |

98.40 |

101.63 |

106.00 |

110.10 |

|

Jul |

102.90 |

104.08 |

103.89 |

111.67 |

|

Aug |

107.87 |

107.09 |

109.00 |

108.49 |

|

Sep |

100.49 |

101.65 |

102.86 |

111.63 |

|

Oct |

98.02 |

105.03 |

109.70 |

114.28 |

|

Nov |

94.82 |

94.24 |

105.62 |

107.74 |

|

Dec |

94.58 |

99.30 |

95.54 |

118.24 |

|

Jan 2020 |

88.86 |

98.46 |

98.42 |

99.97 |

|

Feb |

83.81 |

84.27 |

96.63 |

93.57 |

|

Mar |

82.95 |

98.44 |

99.98 |

96.78 |

|

Apr |

94.95 |

93.75 |

72.36 |

63.37 |

|

May |

87.38 |

90.93 |

78.35 |

74.22 |

|

Jun |

88.53 |

90.77 |

96.81 |

86.72 |

|

Jul |

97.14 |

95.61 |

100.15 |

91.76 |

|

Aug |

96.75 |

97.49 |

101.41 |

86.76 |

|

Sep |

99.67 |

103.92 |

104.85 |

92.32 |

|

Oct |

116.16 |

111.07 |

108.85 |

96.34 |

|

Nov |

103.62 |

105.49 |

98.99 |

96.69 |

|

Dec |

104.73 |

103.94 |

98.68 |

105.93 |

|

Jan 2021 |

103.24 |

103.03 |

96.75 |

88.04 |

|

Feb |

87.88 |

87.96 |

93.45 |

78.74 |

|

Mar |

108.28 |

109.30 |

113.22 |

94.28 |

|

Apr |

99.17 |

102.56 |

103.72 |

86.39 |

|

May |

116.02 |

104.53 |

101.75 |

86.46 |

|

Jun |

98.51 |

101.01 |

108.85 |

92.50 |

|

Jul |

99.57 |

90.93 |

102.85 |

90.69 |

|

Aug |

105.87 |

98.20 |

104.76 |

93.96 |

|

Sep |

98.19 |

97.82 |

104.07 |

97.45 |

|

Oct |

109.18 |

100.83 |

107.59 |

102.97 |

|

Nov |

87.75 |

86.76 |

104.15 |

111.30 |

|

Dec |

94.67 |

89.59 |

100.51 |

117.27 |

|

Sources: Statistics Canada, Transport Canada, Port authorities |

||||

Increased volatility in key global and domestic industries over the past three years has hit the transportation sector particularly hard. While a medium-sized player in the world marketplace, the fact that Canada's success is inextricably linked to our global trade performance means these global trends have an outsized impact on our economy and the affordability of goods here. According to Statistics Canada, transportation costs, while accounting for less than one-fifth of the consumer price basket, were a major driving force in accelerating overall price growth in 2021: transportation costs rose 7.2% compared to 2020 and led all major inflation categories.Footnote 13

Structural challenges also pose risks

While on the surface these pressures and their impacts seem tied to specific events, they also highlight significant structural challenges facing our transportation supply chain.

Climate change poses a risk to our long-term prosperity and must not be overlooked as another driver of instability in transportation supply chains.

As it intensifies, extreme weather events will become more frequent, amplifying the risk of disruptions that could increase financial, economic and transportation impacts in Canada. For example:

- In July 2021, wildfires blocked the main railway lines leading to the Port of Vancouver. At the peak of the crisis, railways' operations were reduced by around 30%, representing around $163 million per day in terms of blocked shipment value. This created congestion at the port and severely impacted the export and import of key commodities such as grain, coal, forestry products, fertilizers and containerized goods.

- In November 2021, flooding in British Columbia hindered the movement of goods estimated to be more than $170 million per day due to lost train capacity, increased congestion at the Port of Vancouver and lost output (i.e., production cuts and lost imports/exports).

- In April and May 2022, flooding in Southern Manitoba affected rail and road traffic, causing delays at a key border crossings and costing up to $200 in additional costs per truck per trip according to the Manitoba Trucking Association.

Still reeling from transportation supply chain issues and changes in consumer demand, businesses have adapted a “just-in-case” mindset to logistics. However, transportation supply chain infrastructure was not designed to operate this way. In major centres like Toronto, inland warehouses and intermodal yards are filled with containers, causing ports to be used as storage yards. The World Bank Group's 2021 Container Port Performance Index ranked the Port of Vancouver 368 out of 370 global ports in terms of its overall performance, with only the U.S. ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles ranking lower.Footnote 14 As recently as September 2022, Maersk advised its North American customers of vessel wait times of 30–44 days at the Port of Vancouver (the highest of all listed North American ports that Maersk calls, with the next closest wait being 20 days). It also noted delays at the ports of Prince Rupert due to inland container congestion; Montreal due to vacation-related labour shortages and to congestion issues with rail and truck availability in Vancouver, Montreal and Toronto.Footnote 15

The transportation sector is feeling labour shortages acutely, particularly in rail and trucking. In its submission to the Task Force, Trucking HR Canada noted that Statistics Canada-reported vacancies for qualified truck drivers reached an all-time high of 25,560 vacant positions from January to March 2022.Footnote 16 As noted by the Conference Board of Canada, the transportation sector is “more reliant on older workers compared to the total economy” and “more than 260,000 of its workers will be retiring in the next 20 years. Moreover, from 2021 to 2030, the number of workers joining the transportation workforce (immigrants, school graduates and other net new entrants) will be insufficient to offset the loss from retirees.”Footnote 17

Canada's transportation supply chain is also affected by delays caused by labour action, even if only threatened. For example, strikes at Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) in 2018 and 2022, Canadian National Railway (CN) in 2019, the Port of Montreal in 2021, and a two-day work stoppage at CP in 2022 all affected how logistics and supply chain decision-makers and international businesses view Canada's reliability as a place to do business. Our reputation as a gateway of choice for international shippers was also severely, and potentially irreparably, damaged by high-profile blockades, including the rail blockades as part of pipeline protests experienced across the country in February 2020, and of key Canada–U.S. border crossings in January 2022 for non-transportation-re-lated political demonstrations. These disruptions had damaging effects on both the national economy and peoples' livelihoods. For instance, the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimated the economic impacts of the 2020 rail disruptions to be $275 million.Footnote 18 In addition, the more recent border blockades were said to have caused economic losses of $3.9 billion in lost and deferred trade, based on testimony provided to the Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities on February 17, 2022.Footnote 19 With many labour agreements up for renewal in 2022 at rail companies and national ports in Canada alone, further disruptions to the transportation supply chain are possible.

Establishing the National Supply Chain Task Force

Against this backdrop of uncertainty, the Minister of Transport and the Ministers of Agriculture and Agri-Food; Employment, Workforce Development and Disability Inclusion; Innovation, Science and Industry; Labour; and International Trade, Export Promotion, Small Business and Economic Development hosted the National Supply Chain Summit in January 2022 to stimulate dialogue with transportation supply chain stakeholders. The Summit focused on the ways in which Government and stakeholders could collaborate and act together to improve our supply chain's resilience, address existing congestion and reliability challenges, and position Canada's transportation supply chain to be domestically and globally competitive in the long-term.

Following the Summit, the Minister of Transport appointed a National Supply Chain Task Force to inform measures taken by the Government. As part of Budget 2022, this includes a $603.2 million investment provided over five years to Transport Canada to build a more resilient and efficient transportation supply chain.

As the members of this Task Force, we have been asked to examine sector-specific challenges and offer independent recommendations on the action that should be taken to improve the fluidity, efficiency and resiliency of our national transportation supply chain — and in doing so, support Canada's economic growth. To this end, we embarked on a consultation process that received approximately 70 written submissions and engaged over 160 transportation supply chain stakeholder organizations and business leaders to examine pressing congestion and fluidity issues in the Canadian and global contexts, and to identify short and long-term actions to alleviate this congestion. For more information on our mandate, membership and consultations, please see Annex A of this report.

Our consultations took place during a time of flux, with the acute problems facing stakeholders continuously shifting. A summary of the industry perspectives on issues affecting Canada's transportation supply chain fluidity and efficiency that we heard during our consultations or received through submissions can be found in Annex B, grouped under the following themes:

- Capacity constraint and infrastructure

- Labour shortage

- Service reliability and resilience

- Supply chain visibility

- Borders

- Regulatory uncertainty

- Planning and governance

We are recommending actions that respond to this changing environment while simultaneously setting the stage to build a transportation supply chain that is flexible and agile now and in the future. We anticipate that acting on these key recommendations will help reduce inflationary pressures and increase economic growth by encouraging private investment in new capacity, building resiliency, and supporting greater system optimization and redundancy.

Our guiding principles

Shaped by the insights and ideas from our stakeholder consultations, our guiding principles are the foundation on which we developed our recommendations. Canada is just one player in a complex, interconnected global network of supply chains, with each having their own structural weaknesses and all facing the same stresses brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. This means that Canada alone is unable to influence or change many factors and issues. We firmly believe, however, that with bold action informed by our guiding principles, and with enhanced collaboration between private operators and government, we can indeed transform our transportation supply chain.

Principle 1: Our mandate is at the heart of all we do

This Task Force was mandated to examine pressing transportation supply chain congestion and fluidity issues in the Canadian and global contexts, and to identify opportunities to collaboratively support a resilient North American and global trade network.

This means our recommendations must aim to achieve two central goals: 1) stimulate and support near-term results, and 2) contribute to lasting improvements to the transportation supply chain.

Principle 2: Our work is built on the foundation of the national public interestFootnote 20

Transportation supply chain issues often seem regionally focused, but because of how we move goods across our geographically diverse landscape, what affects one region affects the entire country. The transportation supply chain's purpose is to ensure businesses and consumers can maximize benefits from the seamless transportation of goods into, out of and around the country. While the impacts of events such as floods, wildfires, strikes, and protests can manifest differently across Canada, our heavy reliance on trade makes the smooth delivery of goods a national public interest. This must remain top of mind as solutions to transportation supply chain issues are designed and implemented.

Also, because the transportation supply chain is multimodal, no means of carrying goods to, from and around Canada can take priority over another.

Currently, Canada's transportation supply chain is made up of a network of companies and modes that are publicly traded, privately held and independently operated — often working in silos rather than as a cohesive system. However, with Canada's economy being increasingly reliant on reliable and agile transportation, the transportation supply chain must begin to operate as a seamless, single entity. Ideally there would be sufficient competition and capacity to produce low-cost, efficient options, as well as motivation and mechanisms for service providers to work together to improve traffic flow. Without these, intervention may be required to ensure the transportation supply chain operates smoothly.

Principle 3: Contributing to Canada's long-term competitiveness and prosperity

Global adoption of practices such as “just-in-time” delivery and of transportation systems built to maximize efficiency and minimize costs created a transportation supply chain unprepared for disruption. As supply chains become more complex, the smallest disruption to a critical component can stop the delivery of goods. At the same time, digital adoption has accelerated across all economic sectors, unleashing the potential for never-before-considered solutions to well-established problems. To successfully compete globally, Canada must keep pace with these changes.

Our current challenges and opportunities are rooted in decades of transportation policy that favoured divestiture. Coupled with the productivity gains brought by the digital age, this has been an effective model up to now. But as population growth has slowed and the impact of the efficiencies gained over the last 30 years has diminished, Canada's competitive position has weakened.

This is in part due to our current models and frameworks, which can't easily adapt to or create transformational change to respond to the competitive dynamics at play in many key sectors. We are also beholden to larger global market forces that have resulted in a high level of consolidation. A limited number of multinational operators control the market, leading to the perception of malfeasance when prices fluctuate or skyrocket.

Given the size of Canada as a market, we have limited power to affect these large-scale global trends. However, rather than approaching this issue as a reaction to a prolonged crisis, we are taking this opportunity to ask all partners throughout the transportation supply chain, “Do we need to do this?” That way, we can help players of all sizes plan for the unforeseen and ensure they have alternative means to move goods to and from market.

Principle 4: Canada's success is a collective effort

Canada has long recognized and benefited from the power of collective action. We now need to build surge capacity into the system and across modes for the long term, but no one entity can build the infrastructure needed to carry us from crisis to growth. It is more essential than ever that all levels of government, Indigenous groups, the private sector and stakeholders in the transportation supply chain collaborate, and that they see their perspectives reflected in our recommendations.

More than physical infrastructure is needed to support Canada's economic growth. Additional public—private collaboration is required to ensure shippers and carriers have access to good analytics and data to identify future opportunities linked to our trade commitments. Levelling the playing field so all partners can compete in the global marketplace also includes bolstering our ability to respond to emerging cyber threats and securing our transportation supply chains across all modes.

Roadblocks to private sector innovation must be removed. Stakeholders across the transportation supply chain have demonstrated their willingness to adapt and collaborate throughout an incredibly challenging time. We must ensure that governments do not place barriers that could stifle this type of much-needed innovation.

While the specific pressures and challenges may differ across the many modes in Canada's transportation supply chain, there are central pillars for action around which we are certain all stakeholders will work collaboratively to bring critical mass to resolving common issues.

Principle 5: Reckoning with the impact of climate change

To address climate change, Canada has committed to reducing its carbon footprint and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. International shippers now expect carbon tracking expertise in ports and across all modes of the transportation supply chain because the lowest carbon emissions possible are needed to be competitive. For example, contracts that currently pay for each move of a container should incentivize reductions in carbon emissions. We must also be prepared to service ships, trucks and airplanes using the newest fuels or battery power. Digitization is an essential tool for optimizing the existing footprint and introducing efficiencies that reduce carbon emissions. The private sector will continue to create new technologies, fuels and tools to reduce the carbon footprint; capitalizing on these innovations requires agile regulatory processes that are responsive to technological advances in a timely way.

While focused on reducing carbon, we also need to prepare for the future impacts of climate change by developing redundancies for chokepoints that can be a single point of failure. Failures could occur anywhere in the country: in the west by mountains, fire or weather; in central Canada by floods; or in the east by winter storms, ice and washouts.

In the North, where the vulnerability of its infrastructure makes adapting to climate change a key priority, significant investments in infrastructure are needed to keep rural and remote communities connected and to enable economic development. This infrastructure can also act as the foundational piece for developing sectors poised for future growth, such as the critical minerals industry. It is vital that goods move to and from the North in a timely way. The changing lengths of seasons and increased storm activity also adds unpredictability and risk in shipping critical supplies and consumer goods to remote coastal and northern communities, via ferries and ice roads. Delayed approvals for moving goods by ice road reduce the time available to build critical infrastructure and bring in needed goods.

Recommendations

The urgency of the supply chain crisis, as well as the critical need for an efficient, resilient and flexible transportation supply chain to facilitate Canada's competitiveness and prosperity, demand actions with both immediate effect and long-term strategic impact. As such, our recommendations for the Government are divided into two categories: A) immediate response actions, and B) long-term strategic actions.

For each category, we have provided a rationale and timeline for each action, an overview of the issues addressed, and the outcomes should all actions be taken. This is followed by a summary table and recommended timeline to complete all actions.

A. Immediate response actions

Our principal recommendations are strategic and will require time to fully develop and implement. In the meantime, we advise the Government to take immediate, concrete actions to begin meaningfully addressing Canada's transportation supply chain challenges. These must begin without delay and be completed within two years to have the desired effect.

Immediate response actions are grouped into two categories: operational shifts and governance shifts. Both categories are critical to addressing urgent supply chain issues and catalyzing systemic change that will address deeply rooted challenges.

To ensure accountability and timely delivery of the immediate response actions, the Task Force recommends that Transport Canada be designated the lead department responsible for executing them, in coordination with other departments and entities as required.

Operational shifts

The Government must intervene quickly and strategically in transportation supply chain disruptions that cannot be resolved by commercial operators. This may include using financial resources to create incentives, introducing penalties, or temporarily waiving regulatory and legal requirements that do not compromise safety. Current issues that require immediate intervention include alleviating port congestion and other bottlenecks, expanding access to labour, and increasing competitiveness. There are critical hot spots (such as congestion in the Pacific Gateway and the Port of Montreal) as well as areas of weakness (such as Northern transportation access) that require action today and an investment in longer term capacity to alleviate constraints. There are numerous actions the Government should take in collaboration with stakeholders to address these issues, including the following 10 operational shifts that we have identified as critical immediate actions to take.

The 10 operational shifts have been grouped according to the critical issue that they address: service reliability and resilience, labour shortages, capacity constraints and infrastructure, and borders.

Service reliability and resilience

1. Concurrently and immediately ease port container congestion.

Rationale: Congestion at port container terminals is in danger of leading to shutdowns. The extraordinarily high volume of import containers arriving at Canadian ports has clogged the transportation supply chain due to insufficient warehousing and reduced transloading capacity (many smaller warehouses and transload facilities shut down during the pandemic). Many inland facilities are at capacity because importers and freight forwarders are using them as de facto storage facilities by delaying the receipt of their containers. Temporary storage areas are required to house at least some import containers off port terminals. This situation could be relieved by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) increasing its capacity to conduct inspections and/or clear containers outside of standard locations. Emergency measures must be taken to avoid backing up the entire supply chain.

Actions:

- The CBSA must permit containers currently being stored at port terminals to be moved in-bondFootnote 21 via rail or truck to inland locations for customs clearance. This will create space at the terminals for arriving vessels to be unloaded. (See Immediate Response Action 10 for related actions.)

- The Government should subsidize the cost of transporting containers inland (like the United States Department of Agriculture does), until the congestion is relieved and container terminals can return to normal operations. Port authorities should be given funds and, if required, the necessary authority to facilitate this activity. Funds should be used to lease land, move containers, provide security and cover other similar costs.

- Regulations and legislation should be revised to empower the Government to take steps to decongest ports where necessary, including levying severe penalties against importers for any container they leave at port for longer than five days.

Timing: Immediate

2. Expand the 30 km interswitch distance across Canada to give shippers more rail options and to address shipper—railway power balance issues. The switch zone rates should be mileage-based and set annually by the Canadian Transportation Agency (CTA). The CTA should also monitor and review the effectiveness of this change.

Rationale: Railways are the only source of transport for many shippers, giving rail companies pricing and service discretion that is not balanced by normal market forces. An expanded interswitch distance option provides increased competition by offering shippers more choices. Note: These immediate actions are in relation to Long-term Strategic Action 5 regarding revising the CTA's mandate to increase competition and balance negotiating power between stakeholders within the supply chain.

Timing: By May 1, 2023

Labour shortages

3. Address immediate labour needs across the transportation supply chain.

Rationale: The need for labour throughout the transportation supply chain is significant. Expediting the entry of skilled and general labour individuals is one way to help address this shortage.

Actions:

- Expand existing programs and examine ways to attract Indigenous workers and other under-represented populations to the sector.

- Continue to support and, if possible, expand the Temporary Foreign Worker (TFW) Program on an urgent basis as it applies to workers in the transportation supply chain.

- Expedite refugee and immigration processing for individuals who have experience in or would be eligible to work for transportation supply chain-related businesses.

- Support businesses, community settlement agencies and other organizations that can help temporary foreign workers, refugees and immigrants acclimate to Canadian work and social environments.

Timing: Immediate

4. In collaboration with provinces/territories, implement programs and policies that encourage the attraction and retention of truck drivers.

Rationale: Truck drivers are required for first and last-mile delivery of freight, as well as for transporting goods across shorter distances. Lack of truck drivers prevents the transportation supply chain from operating efficiently. Access to training programs and their associated costs (approximately $8,000 to $10,000) have been identified as barriers to producing truck drivers, particularly with the introduction of mandatory, entry-level training standards across the country. Because truck driving is not recognized as a skilled occupation, individuals seeking training in this field do not qualify for standard grants or loans and must typically pay for training out-of-pocket. The Government should build on the success of the Canadian Trucking Human Resource Council's Career Expressway Program, which has proven effective for placing recently trained truck drivers with pre-approved employers.

Timing: Immediate

Capacity constraints and infrastructure

5. Complete the twinning of Highway 185, which connects Quebec to New Brunswick.

Rationale: This project has already been announced and funding established. Completion of this project will improve efficiency by creating a link between two portions of the highway that are open to long combination vehicles (i.e., a truck tractor pulling two trailers). Currently drivers must disengage one trailer, transport the other 6 km, return to and re-hook the remaining trailer, and then reassemble the trailer combination to complete their journey.

Timing: Immediate

6. Expedite the approval of winter transport on ice roads.

Rationale: Trucks delivering goods to Northern Indigenous and remote communities require permission to use ice roads. Several federal, provincial, community and private entities are responsible for permitting access to these roads. Any delay in approvals that is unrelated to safety increases the time needed to move goods and resources to these communities and, in some cases, results in goods not being delivered. Because there is only a short window available to use the ice roads, truck drivers generally rush to make their deliveries. Delivering goods across ice roads is perilous and a major safety concern for drivers.

Timing: Immediate

7. Incent or create competition in sustainable pallets to increase additional domestic pallet capacity.

Rationale: Retailers require pallets to move their increasing volume of inventory. Currently, pallets are largely available only through one Australian-owned supplier with Canadian operations, and there is little or no capacity to lease, rent, build or repair pallets within the domestic market.

Timing: Immediate

8. Waive 50% of airport rent payments on a short-term basis to enable airport authorities to invest in capital improvements that enhance transportation supply chain reliability.

Rationale: Airports play a critical role in the transportation supply chain, particularly due to their outsized role in receiving medical supplies and increased business activities related to e-commerce. Capital improvements to their facilities and infrastructure will enhance supply chain reliability. However, given the debt airports incurred during the COVID-19 downturn, financial resources for investment are currently limited. As the Government of Canada waived rent payments from airports during the COVID-19 downturn, the Task Force recommends leveraging a similar approach in order to support capital projects that will increase the reliability and resiliency of the transportation supply chain. This could include requesting the airports provide a list of projects for approval and waiving a portion of rent that could then be allocated to approved projects. The Task Force recommends waiving up to 50% of rent payments for this purpose.

Timing: Immediate

Borders

9. Reopen FAST card enrollment centres and/or consider novel ways to expedite applications.

Rationale: The Free and Secure Trade (FAST) program is a commercial clearance program for known low-risk shipments and drivers travelling between Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. Initiated after 9/11, this program expedites processing for commercial carriers who have completed background checks and fulfill certain eligibility requirements.

While U.S. FAST enrollment centres have reopened following COVID-19 shutdowns, Canadian centres remain closed. As of September 15, 2022, there are approximately 11,000 FAST applications awaiting processing in Canada. Although Canadian truck drivers can access U.S. enrollment centres and CBSA is holding joint enrollment events with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), reopening Canadian enrollment centres will help reduce the queue more quickly.

Without a valid FAST card, truck drivers cannot access the FAST vehicle lanes that expedite crossing at land border ports of entry that serve commercial cargo. Most dedicated FAST lanes are in the heavily used Canada–U.S. border crossings in Michigan, New York and Washington. If trucks that could qualify for FAST lanes end up in non-FAST commercial lanes, this also slows clearance processing times overall.

Timing: Immediate

10. Expand Canadian Food Inspection Agency and other government department services required to process commercial goods at ports, land border crossings and airports to offer 24/7 services as needed. Use auto-mation, technology and other mechanisms to increase the efficiency of inspections (as an added benefit, this will also help address labour shortages).

Rationale: Government must act quickly to ensure it does not exacerbate delays that lead to congestion. Ensuring prompt service from all necessary government agencies will help in this regard. This recommendation is tied to the short-term actions previously detailed that relate to easing port congestion and improving efficiencies of the cargo clearance operations of the CBSA.

Timing: Immediate

|

Issues addressed |

Outcomes achieved |

|---|---|

|

|

Governance shifts

In addition to the immediate steps the Government must take to address severe supply chain disruptions and constraints, quick action must also be taken to invest in our long-term transportation supply chain strategy. Implementation of these three shifts in governance will be a catalyst for systems-level change required for the long-term strategic actions detailed in the next section of this report. Implementation should begin immediately with Transport Canada leading and coordinating across departments and should be completed within one to two years.

11. Establish, fund and hire staff for a Supply Chain Office.

Rationale: A Supply Chain Office is needed to provide leadership and oversight of our recommendations. This must be done quickly to maintain momentum generated by improvements to the transportation supply chain and to signify the importance of ensuring it is reliable, resilient and flexible.

Timing: Within 12 months

12. Develop a long-term transportation supply chain strategy, including initiating a review to update and modernize related regulations.

Rationale: Creating a comprehensive and long-ranging strategic plan requires sufficient time for intense consultation and engagement with various levels of government, Indigenous groups, industry stakeholders and others.

Timing: Begin immediately

13. Develop a transportation supply chain labour strategy.

Rationale: Having insufficient workers to provide services is a significant issue. Transportation supply chain problems cannot be resolved without many additional skilled and general labour workers. A national transportation supply chain labour strategy is needed urgently because the health of our economy depends on the transportation supply chain.

Timing: Begin immediately

|

Issues addressed |

Outcomes achieved |

|---|---|

|

|

B. Long-term strategic actions

The Task Force recommends that the Government prioritize and invest in eight long-term strategic actions to both initiate the systemic change required to drive the long-term competitiveness, prosperity and sustainability of Canada's transportation supply chain, and to maintain appropriate governance of the transportation supply chain going forward. A functional and reliable transportation supply chain is essential to ensuring Canada's ability to fully and competitively participate in the global market.

1. Establish a Supply Chain Office to unify the federal government's responsibility/authority over transportation supply chain management across departments.

Rationale: Dividing responsibility for the national supply chain among numerous government departments negatively affects its management. Without a cohesive view and singular accountability for the transportation supply chain, including monitoring and reporting on key performance indicators (KPIs), departmental actions could negatively affect overall productivity. An overarching perspective that spans government departments and jurisdictions is urgently needed to help establish clear accountability and to mandate action that supports a high-functioning, reliable, resilient and adaptable supply chain.

Actions: The Government should establish an independent Supply Chain Office (SCO) to provide national oversight of the transportation supply chain; to direct, monitor and manage supply chain issues; to implement the national transportation supply chain strategy; and to coordinate the legislative and regulatory impacts on supply chains across government departments.

The SCO should be responsible for:

- Developing, implementing and sustaining the national transportation supply chain strategy (as described in Long-term Strategic Action 2).

- Establishing long-term national transportation supply chain-related priorities (in line with the national transportation supply chain strategy) and ensuring funding is subject to multi-year budget allocations, disbursed based on national priorities and is not constrained by budgeting processes or provincial/ regional equity principles. This includes ensuring funding is coordinated across the transportation supply chain for efficiency and effectiveness.

- Leading federal government policy and regulation related to the transportation supply chain, including coordinating across federal entities and managing government KPIs.

- Reporting on SCO activities and performance against the transportation supply chain KPIs identified in the national supply chain strategy.

- Initiating action when transportation supply chain KPIs are not being met.

- Evaluating the effectiveness of investments made by programs such as the National Trade Corridors Fund to ensure sufficient ongoing resources are available for projects (as identified in the national transportation supply chain strategy) and infrastructure investments are aligned with national opportunities and strategies, including anticipating technological change.

- Developing and maintaining risk and sustainability functions to monitor evolving transportation technologies, infrastructure and processes to inform future infrastructure investment.

- Working with industry to effectively manage the transportation supply chain, including data and information sharing as well as preparing for and encouraging the use of technologies that will improve the supply chain's fluidity and resiliency.

- Overseeing, coordinating and monitoring government–industry transportation supply chain crisis working groups in each province, in the territories and at the federal level to prepare for and to mitigate unplanned disruptions (e.g., BC Floods Working Group), particularly those related to natural disasters.

- Compelling the resolution of conflicting government requirements placed on transportation supply chain stakeholders.

- Creating regulatory certainty by:

- » Establishing a major project management office to coordinate and streamline approval processes and evaluate the effectiveness of projects.

- » Ensuring departmental mandates consider transportation supply chain impacts when developing legislation, regulations and policies.

- » Developing a single “window” for regulatory reporting purposes across government by treating stakeholders as customers and asking them to comply in whichever way is easiest way for them (rather than simplest for government), and by making differences in requirements the exception rather than the rule.

|

Issues addressed |

Outcomes achieved |

|---|---|

|

|

2. Finalize, implement and regularly renew a long-term, future-proof (30 to 50-year) transportation supply chain strategy.

Rationale: Lack of strategic coordination has been a significant driver of the challenges facing the transportation supply chain. If not addressed, this will continue to inhibit Canada's ability to resolve both longstanding and emerging issues for the benefit of the national public interest. A strategy is needed to provide a comprehensive response to current issues and to develop appropriate governance, planning and accountability for the long term.

Creating a transportation supply chain strategy will:

- Build a comprehensive transportation supply chain vision that is adaptable and responsive to a shifting macroeconomic environment

- Allow all levels of government, investors, commercial operators and other stakeholders to better plan, including through supply chain visibility, data and analytics

- Indicate that Canada is a reliable trading partner

- Identify and plan for strategic and long-term transportation supply chain investments

- Increase the attractiveness of Canadian transportation supply chain infrastructure projects to private investors, including Canadian pension funds

- Define the role of key players and ensure their agreement and collaboration

- Develop a technological roadmap to digitalize, automate and incorporate new technologies across the transportation supply chain

Actions: The SCO (described in Long-term Strategic Action 1) should finalize, implement and sustain the national supply chain strategy. It should assume responsibility for the strategy from Transport Canada (as described in the immediate response actions section) and continue its work — namely, consulting with other federal entities, the provinces and territories, municipalities, Indigenous groups, industry and various interest groups to complete the initial strategy.

The Canada Infrastructure Bank could be leveraged to prioritize public–private investments in the infrastructure that best advances the national public interest as identified in the strategy.

The strategy should be:

- Focused on domestic, North American and global transportation supply chains.

- Centred on specific goals with KPIs such as improved fluidity, resiliency, efficiency, accountability and international competitiveness; safe, secure and sustainable operations (including carbon footprint by mode); a fit-for-purpose regulatory environment; innovative solutions to meet freight demand; an adaptable workforce; and an informed understanding and acceptance of freight operations.

- Established with a perspective on multiple timelines, including developing and implementing plans in short and medium-term intervals within the 30–50 year period.

- Revisited at least every five years to make adjustments needed due to changes in economic, political, technological, social or legal environments.

The strategy should address, at minimum:

- Identification of current bottlenecks and infrastructure under-utilization.

- All modes of transport related to the transportation supply chain, including:

- » Passenger and freight transportation infrastructure.

- » Port and marine infrastructure, particularly planning, investment and prioritization for three distinct and strategic marine gateways: West Coast, Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway and East Coast. Inclusion of specific ports and marine infrastructure in each gateway will be determined by the Government.

- All transportation corridors and gateways.

- Local community planning needs.

- Port modernization that provides ports with more authority (e.g., extending to inland ports), financial flexibility (e.g., raising financing maximum), autonomy (e.g., airport authorities model) and governance, including more user representation and more effective dispute-resolution mechanisms (for disputes between port authorities and their tenants or other stakeholders over whom authorities have influence).

- Relevant supply chain-related KPIs from individual government departments that can impact the transportation supply chain, such as the CBSA, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). These KPIs would measure the extent to which government departments affect supply chain performance.

- Perspectives on the recommendations of the 2015 Canada Transportation Act Review Report regarding the North.

- Technologies and automation roadmaps in the logistic supply chain decarbonization plan to help Canada achieve national net-zero targets.

|

Issues addressed |

Outcomes achieved |

|---|---|

|

|

3. Digitalize and create end-to-end supply chain visibility for efficiency, accountability, planning, investment and security.

Rationale: Canada is behind in using technology to improve and modernize its transportation supply chain processes. An intense and urgent focus on digitalization is needed to compete internationally and become a global leader. A national transportation supply chain data strategy as well as a Government-led, industry-wide data-sharing commitment are needed to improve visibility, competitiveness, resiliency and agility. This will also enable informed Government intervention where necessary to address disruptions and other critical issues. Successful implementation of a national transportation supply chain data strategy requires both government and industry cooperation, as well as a significant shift in behaviour by all industry stakeholders.

Actions: On behalf of the Government, the SCO should develop and execute a national supply chain data strategy to:

- Digitalize the transportation supply chain.

- Create the environment and data structure (data governance) to enable and standardize the exchange of data from all groups involved.

- Create predictability in demand forecasting for the end-to-end transportation supply chain across government and stakeholders.

- Respond to the unique nature of Canada's transportation supply chain, including addressing visibility for users of all modes of transport: rail, marine (via ports or ferries, other cargo vessels), truck and air, as well as connections between and among these modes.

- Engage stakeholders and ensure all parties will coordinate and share data and agree on data sharing and what level of information is required to improve the end-to-end transportation supply chain performance, without impacting business competitiveness.

Change management, data governance, data security and implementation are the key elements needed to build the foundation for this data strategy.

Change management

- Identify a leader who reports to the SCO and will be responsible for uniting stakeholders and delivering the digitalization project. This will ideally be a leader from the industry who has digital transformation experience, knowledge of government and the ability to engage all transportation supply chain stakeholders.

- Ensure that each player benefits from sharing data and that exporters and importers are required to share their demand forecasting data to help all modes of transport better manage their services. This is a win-win for government and transportation supply chain stakeholders, and these benefits must be clearly communicated. However, participation will likely need to be compelled through incentives and penalties, as it must be compulsory to ensure data sharing and visibility.

- Identify existing data available and map all processes and sources of data.

- Identify stakeholders that will be involved in data sharing to define common goals and objectives. Industry must be highly involved in the project definition, and we recommend that existing roles and structures (such as chief information officers and data-sharing communities) are leveraged for their expertise.

- Provide visibility with quick wins that will reduce existing bottlenecks and demonstrate the dynamism and intent to modernize data infrastructure. This can be done with a common plan to deliver MVPs (most viable products) that will help test the process and stakeholder alignment.

- Create communication and training plans for the stakeholders, teams and customers who will be using the transportation supply chain data system.

- Ensure Indigenous communities can access digital data related to the transportation supply chain for decision-making (where appropriate), and provide these communities with financial support and assistance to build data production capacity.

Data governance

- Develop and implement an appropriate governance model that respects confidentiality and commercial sensitivity.

- Define the standards and means by which transportation supply chain operators can exchange data so as to improve efficiency and reliability.

- Define information taxonomy, data-sharing methodology and protocols (including requirements for data to be timely, interoperable and accurate), and include the necessary data to support the national public interest.

- Invest in the creation of data sharing infrastructure where data from all entities will be received.

Data stewardship

- Identify external provider(s) to develop and manage a digital data-sharing platform/environment that leverages artificial intelligence and advanced analytics.

- Establish an external board or group consisting of representatives of key supply chain sector participants to ensure collection and distribution of digital data.

- Identify and fill key data gaps through partnerships with third parties, encourage and offer incentives to induce voluntary participation, and, if necessary, levy penalties for failing to provide compulsory data submissions.

Data security

- Ensure Canada's cyber security strategy addresses risks to transportation supply chains for critical commodities.

Implementation

- Use existing and enhanced regulatory capability to compel major stakeholders to make available the necessary capacity and forecast data, which will help better manage the national transportation supply chain.

- Create incentives such as grants and tax credits to accelerate the digitization of medium and small businesses.

- Enhance the role ports and airports play in leading the digitization of the transportation supply chain.

|

Issues addressed |

Outcomes achieved |

|---|---|

|

|

4. Immediately address Canada's significant transportation supply chain labour shortage.Footnote 22

Rationale: By 2030, the percentage of Canadians over the age of 65 is expected to nearly double. As most people over the age of 65 are no longer in the workforce, there will be fewer and fewer people to fill vacant positions in the transportation supply chain. In addition, the number of unemployed people has reached an all-time low, sitting at 1.2 million as of June 2022. The proportion of non-working-age people (those younger than 15 or older than 64) to the working-age population is also increasing: Canada's dependency ratio (the number of “dependents” for every 100 workers) was 44% in 2010 and 52% in 2021. It is projected to grow as high as 59% by 2028 with at least five million Canadians set to retire by the end of this decade.

Canada's labour force growth is on course to stagnate unless dramatic steps are taken. Currently, immigration accounts for almost 100% of labour force growth. We also have a low birth rate, with the highest being found in Indigenous communities (2.6 compared with 1.5 for the Canadian population as a whole). The number of skilled and general labourers will be the limiting factor in our economic growth potential. Plus, without a robust workforce, there will not be sufficient tax revenue to support the programs and benefits Canadians rely on, including healthcare and education.Footnote 23

Actions: The Government should finalize and execute the transportation supply chain labour strategy to address Canada's significant labour shortage (see Immediate Response Action 13). The strategy should cover, at minimum, the following streams: immigration, domestic labour participation, refugees, training and education,productivity, and automation.

Immigration

- Adapt immigration policies to prioritize individuals with transportation supply chain experience and skills (or with the aptitude for transportation supply chain positions), and to fast-track their applications.Footnote 24 Both skilled and general labour workers are needed and must be prioritized.

- Recognize international credentials and experience related to transportation supply chain positions.

- Ensure sufficient social and other supports (e.g., housing) can be accessed when immigrants arrive in Canada to fill transportation supply chain positions. It is critical that immigration policies incorporate the required investment in infrastructure and social services to accommodate and support population growth.

Domestic labour participation

- Remove barriers, educate/train and support under-represented groups (such as women, Indigenous people, people with disabilities and people of colour) who have the experience and/or aptitude to be transportation supply chain workers. For example, attracting Indigenous youth could be achieved by:

- » Ensuring key positions are supported with mentoring, training and opportunities for on-the-job skills development.

- » Building competencies for transportation supply chain positions by providing special access to Indigenous youth.

- Reform tax and related policy to encourage older people to remain in the workforce (or at least not discourage them from working, even on a part-time basis).

Refugees

- Educate/train and support refugees who have the experience and/or aptitude to be transportation supply chain workers.

Training and education

- Work with industry to increase awareness of the importance and value of transportation supply chain positions.

- Collaborate with the provinces/territories to align training programs and funding to support key transportation supply chain positions across all transportation modes, and to establish programs that will be recognized across Canada (i.e., ensuring certifications, designations, etc. are transferrable).

- Promote awareness of continuous training and upskilling as lifelong and necessary requirements to succeed in Canadian workplaces.

- Invest in supporting the adoption of and transition to automation to maintain competitiveness.

Productivity

- Apply a transportation supply chain lens to new or revised requirements to ensure changes do not negatively affect the labour supply or the ongoing participation of workers in the transportation supply chain.

Automation

- Provide small and medium-sized businesses with funding and incentives for automation to speed up adoption and enhance competitiveness.Footnote 25

- Review policies and regulations to adapt to the changing nature of transportation supply chain operations and decision-making brought about by automation and technological advancement.

- Help communicate to workers that automation will not limit their opportunities.

|

Issues addressed |

Outcomes achieved |

|---|---|

|

|

5. Revise the Canadian Transportation Agency's mandate and provide it the independence, authority and commensurate funding needed to deliver on that mandate.