Evaluation report outlining results of the Lessons Learned Review of the Remote Air Services Program at Transport Canada.

On this page

- Context and Program Information

- Review Objectives, Scope and Methodology

- Summary of Key Observations

- Need for the RASP

- Achievement of Expected Outcomes

- Summary of RASP Success Factors and Lessons Learned

- Success Factors

- Lesson Learned

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: List of Acronyms

Program information

Program background

- The Remote Air Services Program (RASP) was created after carriers that provided air services to remote communities began to suffer massive revenue losses in spring 2020 due to COVID-19 and could not maintain service.

- Approximately 140 remote communities were identified by Transport Canada (TC) as relying on air service as the only practical year-round mode of transportation.

- 21 core small air carriers provided scheduled service to remote communities for the movement of essential workers, patients, food, supplies, medicines, and medical testing equipment and samples.

Definition of a remote community

Communities are considered remote when air travel is used for essential needs (e.g., medical visits and personnel, food, first responders, or laboratory samples), and other travel alternatives (such as roads, rail or marine shipping) are non-existent or impractical.

Program objectives

- To support a focused and reliable air network for the movement of essential goods and services to remote communities

- To ensure there is a continued minimum level of essential air carrier services to remote communities.

Funding and delivery

- $174M (of which $173.1M is contribution funding) in total

- Allocated to Provinces and Territories (PTs) via bilateral agreements and flowed to PTs through three 6-month long phases:

- Phase 1 (from July to December 2020)

- Phase 2 (from January to June 2021)

- Phase 3 (from July to December 2021)

- *Extended beyond Phase 3 to March 31, 2022, to allow for spending of unexpended funds

- PTs were responsible for administering the RASP. Specifically, TC transferred funding to PTs, who were responsible for selecting which carriers would receive assistance and determining how much funding would be allocated to each carrier, based on the objectives for the program and in accordance with the terms and conditions of the funding agreements.

- Funding was to be used by carriers to maintain the minimum level of air services required for the movement of essential goods, services, and travel to remote communities. This could include, but was not limited to, the cost of operating the aircraft, fuel, labor, aircraft maintenance, landing and hanger fees, equipment, and leases after July 1, 2020. The funding could not be used at any point to support capital expenditures incurred by air carriers, or administrative expenditures incurred by PTs.

Review objectives, scope and methodology

Objectives: To assess the relevance, design, and delivery of the RASP, as well as any observed program results, with the aim of identifying best practices and lessons learned. The intent is to inform future similar programming (i.e., short-term programs with a focused purpose). The review is also intended to complement a joint Internal Audit and Evaluation Review of COVID-19 Temporary Measures completed in summer 2022.

Scope: The Review is focused on phases 1 and 2 (July 2020 to June 2021). Due to timing constraints, reporting data for phase 3 was not available for our analysis. However, there is no indication that the conclusions of this review would be meaningfully different with the inclusion of phase 3 reporting data.

Review Questions:

- To what extent was there a need for the RASP?

- To what extent did the program meet its objectives?

- What were the key lessons learned and best practices identified regarding the design and delivery of RASP?

Methodology

- 11 external interviews

- - 8 PT representatives

- - 3 carrier representatives

- 3 Internal interviews

- Media scan

- Document Review

Limitations: Despite the review team's best efforts, only three out of 44 carriers contacted accepted to be interviewed.

Summary of key observations

Need for the RASP

- There was a clear and immediate need for a program like the RASP to support continued air service and movement of goods and people in remote communities.

- The pace of recovery in travel to RASP communities varied amongst PTs.

- The RASP was complementary to, and not duplicative of, other federal or PT programs aimed at supporting air access to remote communities.

Achievement of expected outcomes

The RASP enabled carriers to maintain essential air services to most remote communities through funding contributions, which offset the operational losses caused by limited passenger demand.

For Phases 1 and 2, the Program has met the service standard to provide funding to PT governments within a certain number of days after signing the contribution agreements, apart from one case in Phase 1.

The RASP funding did not always get to air carriers expeditiously. However, there is no evidence of noteworthy impact on carrier operations or the achievement of program outcomes.

TC determined, based on the carrier flight numbers reported by PTs, that a reliable air network to remote communities was maintained.

Success factors

- Availability of useful, in-depth carrier and other data at TC

- Working definition of a remote community, developed in consultation with PTs

- More PT control in program delivery: up to PTs to determine how to allocate RASP funds

- Light, flexible contribution agreements

- TC practice of frequent, frank communication with stakeholders

Lesson learned

The flexibility built into the RASP and the effective communication approach adopted by TC program staff helped PTs and TC successfully navigate through challenges such as the initial exclusion of charters and other unforeseen events.

Need for the RASP

There was a clear and immediate need for a program like the RASP to support continued air service and movement of goods and people in remote communities.

Remote communities in Canada's North rely on an air network to maintain the movement of necessary goods, services, and people.

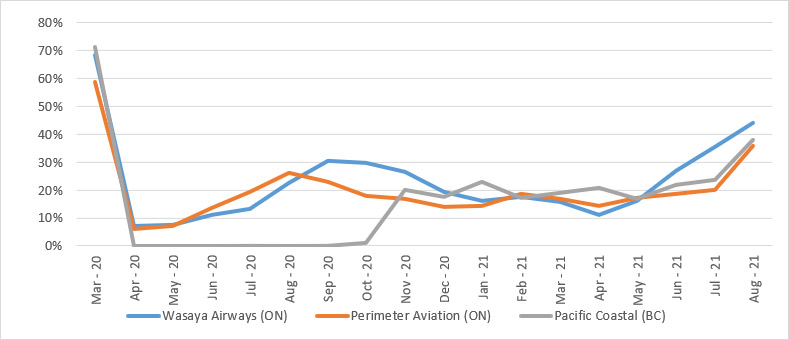

As figure 1 below shows, air travel declined precipitously after March 2020, when the pandemic first hit. Without federal government support there was a real danger that some carriers would stop flying certain routes, or even cease operations altogether. This would have had devastating effect on many of Canada's remote communities, who depend on air services to receive medical and other supplies.

Figure 1: Passenger Volumes of Select Carriers (RASP communities only)

Alternative text for Figure 1:

Figure 1, Passenger Volumes of Select Carriers for RASP communities displays a line graph, illustrating the passenger volumes for three airlines from March 2020 to August 2021. The three airlines are Wasaya Airways, based in Ontario, Perimeter Aviation based in Manitoba and Pacific Coastal, based in BC. In March 2020, passenger volumes for the three airlines ranged from just under 60 percent to just over 70 percent. By April 2020, passenger volumes for Pacific Coastal were nearly 0 percent. Wasaya Airways and Perimeter Aviation dropped to under 10 percent. Until July 2021, there was fluctuations both up and down for the three airlines, after which the airlines saw continuous improvements in passenger volumes.

All interviewees stated that the RASP filled an important need during the pandemic. In particular, both PT and carrier interviewees stated consistently that the RASP funding was important for carriers to have the financial security needed to maintain their financial viability throughout the COVID-19 shutdowns and travel restrictions. Several interviewees stated that in the aviation industry, particularly in the north, margins are slim and operations have high overhead costs that are not easy to reduce. If a company declares bankruptcy and ceases operations, it is difficult to bring it back. Further, there is a limited pool of skilled employees; if they are not retained, it can be challenging for carriers to find suitable replacements.

There was a clear and immediate need for a program like the RASP to support continued air service and movement of goods and people in remote communities.

The next few pages will show that, after the initial precipitous decline in March and April 2020, air travel fluctuated and, over time, generally began recovering, indicating that the RASP was needed as temporary support for most PTs, and not as a long-term subsidy.

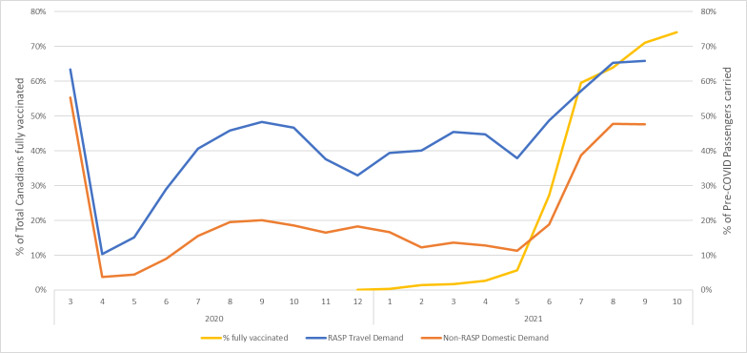

As Figure 2 shows, after the pandemic hit in March 2020, air travel levels (both in the RASP communities and in Canada in general) oscillated, driven primarily by public health orders and vaccination rates. Beginning in the spring of 2021, passenger travel volumes began to recover, mirroring the increase in Canadian vaccination rates.

Figure 2: Vaccination Rates vs RASP and Non-RASP Travel Demand in Canada – 2020-2021

Alternative text for figure 2:

Figure 2, Vaccination Rates vs RASP and Non-RASP Travel Demand in Canada – 2020-2021 is a dual y axis line graph. Y1 represents the percentage of total Canadians vaccinated while the secondary y-axis represents the percentage of pre-COVID passenger travel. Both y axes are in increments of 10 percent. The x axis represents time in increments of one month, starting from 03/2020 and ending at 10/2021. The line graph illustrates the steep fall of travel demand with the onset of the pandemic, initial gains over the next few months, followed by ongoing fluctuations in both RASP and non-RASP domestic travel demand. It also illustrates an upward trend in demand that coincides with steep increases in the total percentage of Canadians that are fully vaccinated. At 03/2020 RASP travel demand is 63 percent, then falls to 10 percent by 04/2020. It then increases to 48 percent at 09/2020, then 33 percent by 12/2020, then 45 by 03/2021 and then 38 percent by 05/2021. Non-RASP domestic travel demand is 55 percent at 03/2020 and falls to just under 4 percent by 04/2020, then 20 percent by 09/20 and 11 percent by 05/2021. It is only once the total percentage of Canadians fully vaccinated begins to increase exponentially, going from 5.7 percent at 05/2021 to approximately 60 percent at 07/2021 does travel demand for both RASP and non-RASP domestic stabilize into an upward trend. RASP travel demand increased from 38 percent at 05/21 to 65 percent at 08/2021 while non-RASP domestic travel demand increased from 11 percent to 48 percent over the same period.

However, as we will show in the next page, there was variance among PTs in terms of the pace of recovery of scheduled passenger service to remote communities.

The pace of recovery in air travel to RASP communities varied amongst PTs.

Figure 3 shows that while all PTs eligible for RASP funding showed a significant initial drop, air travel in some PTs recovered faster than in others. For example, the Electronic Collection of Air Transportation Statistics (ECATS) data shows that, taking 2019 as the baseline, scheduled passenger service to remote communities in Manitoba had recovered to over 60% of the pre-pandemic levels by July 2020. In contrast, scheduled passenger volumes in the Yukon had recovered to 25% of pre-pandemic levels by July 2020, and reached a high of only 48% by July 2021.

Figure 3: Recovery of passenger volumes on scheduled services compared to pre-pandemic levels (2019 as the baseline year; RASP communities only)

Note 1: Recovery numbers for Newfoundland & Labrador were not included in this table because, for part of 2020, data to the province was reported quarterly, instead of monthly.

Note 2: Newfoundland & Labrador and Alberta did not participate in the RASP.

While uneven, the recovery of scheduled passenger service to remote communities suggests that the RASP was needed as a temporary support measure for PTs and not as a long-term subsidy. However, we note that by July 2021, the average recovery was still at roughly 60% of the pre-pandemic levels; Phase 3 reporting would need to be examined to confirm whether the upward trend noted in this review continues.

The RASP was complementary to, and not duplicative of, other federal or PT programs aimed at supporting access to remote communities.

Other Federal Programs

Early in the pandemic, the federal government allocated $17.3 million to the Territories to ensure a continued supply of essential goods and services to communities in the short term. This initial funding was administered by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC). Program documents noted that other federal programs specifically designed to maintain air service to remote communities expired on June 30, 2020, and therefore did not overlap with the RASP.

PT programs

While some provinces and territories provided additional sector funding support, those programs were intended to complement, and not overlap, with the RASP. For example, in December 2021, Manitoba announced the Charter Transport Recovery Program, a fund of up to $1.92 million to support bus and air charter companies affected by the COVID-19 public health restrictions. Manitoba's program explicitly stated that only costs not covered by other relief programs could be claimed.

Other provincial programs and subsidies were likewise designed to complement federal support and avoid program duplication. These included:

- $40 million from the Province of Québec to support access to its remote locations for five carriers.

- $24 million from the Government of Nunavut to support Canadian North and Calm Air.

- $2.95 million from the Government of the Northwest Territories for 10 airlines and rotary wing operators in the Northwest Territories.

There was also an expectation that PTs "confirm and take into account if air carriers have applied for the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS)". Carrier interviewees stated that, while RASP was their primary source of funding support, they indeed also made use of CEWS , which was noted as very helpful to airlines in maintaining their staffing levels by providing funds to offset employee salary costs. Interviewees also noted the Canada Emergency Rent Subsidy (CERS) as helpful to offset ongoing fixed costs such as rent.

Achievement of expected outcomes

The RASP enabled carriers to maintain essential air services to most remote communities through funding contributions, which offset the operational losses encountered due to limited passenger demand.

Evidence shows that the RASP achieved its overall goals of funneling funding to carriers and ensuring continued minimum level of essential air service to remote communities.

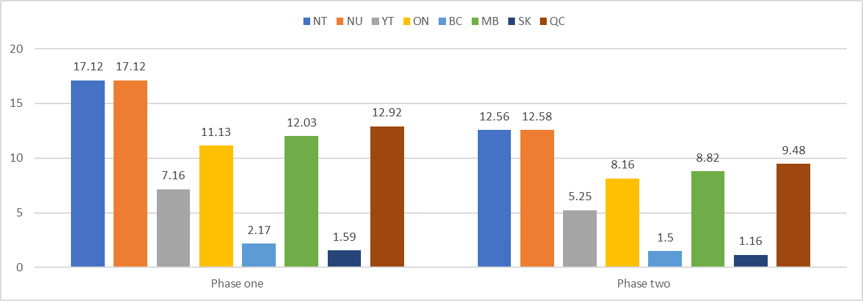

- According to TC program documents, through Phases 1 and 2, $109M in federal contributions were funneled to 56 air carriers in eight PTs. While most funding was allocated to scheduled services, in some instances, PTs also funded chartered operations, which they assessed as necessary to maintain air services to remote communities in their jurisdictions.

Graph 1: TC RASP Funding (in millions) to Provinces and Territories - Phases 1 And 2

Alternative text for Graph 1:

Graph 1 is a bar graph illustrating the amount of RASP funding air carriers received in each province or territory for both Phase 1 and Phase 2. In Phase 1 NT and NU received 17.12 million, YT 7.16 million, ON 11.13 million, BC 2.17 million, MB 12.03 million, SK 1.59 million, QC 12.92 million. In Phase, 2 NT received 12.56 million, NU 12.58 million, YT 5.25 million, ON 8.16 million, BC 1.5 million, MB 8.82 million, SK 1.16 million and QC 9.48 million.

- Between July 2020 and December 2021, 100% of remote communities retained essential air service for the movement of people and goods.

- As of January 2022, 100% of remote communities had scheduled service without government subsidy.

- There were no bankruptcies amongst carriers who received RASP funding.

In the next few slides, we will examine in greater detail the timeliness of funding flows to PTs and carriers, and the extent to which minimum level of air service was maintained.

For Phases 1 and 2, the Program has met the service standard to provide funding to PT governments within a certain number of days after signing the contribution agreements, apart from one case in Phase 1.

- Providing funding to those who need it in a timely manner is especially important for temporary measures like the RASP, which was created specifically to respond to an emergency.

- The program's contribution agreements state a 30-business day service standard (Phase 1 payment), and budget letters state a 20-business day service standard (Phase 2, onwards).

- Table 1 below shows the timing of funding flows to PTs. All Phase 1 funding agreements were signed with eligible PTs (excluding Newfoundland & Labrador and Alberta which did not participate in the RASP), and funds transferred by the end of the 2020-21 fiscal year. The service standard was nearly always met.

| PT | Phase 1 Agreement Date | Phase 1 Payment Date | Service Standard Met? | Phase 2 Budget Letter Date | Phase 2 Payment Date | Service Standard Met? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 10-05-2021 | 17-09-2021* | Yes | 08-11-2021 | 10-11-2021 | Yes |

| Ontario | 15-01-2021 | 29-01-2021 | Yes | 03-05-2021 | 10-05-2021 | Yes |

| Manitoba | 15-01-2021 | 29-01-2021 | Yes | 03-05-2021 | 10-05-2021 | Yes |

| Saskatchewan | 03-03-2021 | 17-03-2021 | Yes | 03-05-2021 | 10-05-2021 | Yes |

| British Columbia | 23-12-2020 | 27-01-2021 | Yes | 03-05-2021 | 10-05-2021 | Yes |

| Yukon Territory | 30-10-2020 | 01-01-2021 | No | 03-05-2021 | 10-05-2021 | Yes |

| Northwest Territories | 15-09-2020 | 25-09-2020 | Yes | 03-05-2021 | 07-05-2021 | Yes |

| Nunavut | 29-09-2020 | 16-10-2020 | Yes | 11-05-2021 | 01-06-2021 | Yes |

*As per the terms of Quebec's agreement, the service standard was triggered on the date the claim was approved by TC (08-09-2021) rather than the date the agreement was signed.

The RASP funding did not always get to air carriers expeditiously. However, there is no evidence of significant impact on carrier operations or the achievement of program outcomes.

Once the funds were transferred to the PTs, they had the responsibility for transferring the money to carriers in their jurisdictions. There was no requirement for PTs to report to TC on the timeliness of their provision of funds to carriers. Carrier interviewees noted the delay in receiving phase 1 funding, with one interviewee stating that they did not receive the first funding transfer until January 2021. However, interviewees stated that subsequent funding transfers were timelier. Carrier interviewees also acknowledged the difficulty governments faced in quickly setting up a new program and disbursing funds.

PT interviewees also reported that carriers did not always feel that they received the funds in a reasonable timeframe. Further, some PTs stated that confirmation and signed funding agreements were only finalized towards the end of each funding period. TC interviewees acknowledged that phase 1 funds did not start flowing to the PTs five to six months after the initial program announcement.

Almost all interviewees noted that, in the summer and fall of 2020 when there was significant uncertainty about the potential impacts on the air sector of the COVID pandemic, the key was to reassure PTs and carriers that funding would eventually be provided, and this was largely accomplished.

Several factors impeded the expeditious receipt of funds by carriers. Frequent decisions from and touch bases with Central Agencies were required in order to secure funding which in turn resulted in funding agreements being finalized towards the end of each funding period. In addition, each PT had their own cabinet approval process, which, according to TC program staff, added to the timelines.

While this review focused on RASP Phases 1 and 2, it is also worth noting that the 2021 federal election delayed the approval and disbursement of funds for Phase 3. On August 15, 2021, the Parliament was dissolved, and writs of election were dropped. At that point, it became too late to submit a funding request for Phase 3 to the Minister of Transport. There was an assumption that the request could be sent to the Minister shortly after the conclusion of the election on September 20, 2021. That did not happen, primarily because the program Terms and Conditions were slated to expire at end of calendar year. The program worked with TC's Centre of Expertise on Funding Instruments to amend the Terms and Conditions and to create addendum agreements which allowed for the Phase 3 payments. These addendums were also used to introduce the 3-month extension phase of the program. We note that, for Ontario and Quebec, TC drafted new RASP agreements instead of addendum agreements, due to their preference for this option. Significant discussions with Central Agencies were required to extend elements of Phase 3 to utilize the program budget and to maximize program outcomes.

While the timing of funding at times presented a challenge to PTs and carriers, there is no evidence of a noteworthy impact on the achievement of program outcomes. That said, for a future similar temporary measure in response to an emergency, it is prudent to consider ways, such as building in additional time in the program Terms and Conditions, that could help mitigate the impacts of unforeseen circumstances on program delivery timelines. Building in flexibility to change elements of program design to deal with persisting or resurging emergencies or crises (e.g., the continued need for the program during and post-Omicron) would also help give the Department and recipients longer term certainty.

TC determined, based on the carrier flight numbers reported by PTs, that a reliable air network to remote communities was maintained.

To determine the number of flights needed to maintain the minimum level of air service necessary to support a reliable air network, TC requested that PTs provide an estimate of the number of flights that the RASP funded carriers made to the remote communities identified by TC. Our understanding is that each PT used its own methodology to determine the minimum number of flights needed, based on pre-pandemic ECATS data. Table 2 shows the minimum number of estimated flights to remote communities by PT:

| Province/Territory | Phase 1 | Phase 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Northwest Territory | 4439 | --* |

| Nunavut | 5928 | 5928 |

| Yukon Territory | 418 | 832 |

| Ontario | 10469 | 29089 |

| BC | 970 | 1770 |

| Manitoba | 8153 | 6620 |

| Saskatchewan | 7540 | 7512 |

| Quebec | 2351 | 4548 |

* NWT was unable to provide firm numbers for phase 2. To fulfil reporting requirements NWT instead provided TC with a chart showing the necessary routes that were maintained.

After each RASP phase, TC would follow up with PTs for confirmation that the initial estimates of the number of flights provided by PTs were achieved. PTs would typically respond with a simple confirmation, with some PTs occasionally providing a breakdown of flights by carrier, or by scheduled vs. chartered operations.

Some interviewees remarked that carriers occasionally needed to adjust operations in response to an evolving pandemic environment, as well as to remain responsive to changing interim orders from both TC and other government departments such as Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). That said, according to TC program staff, their process based on PT reporting on the number of flights allowed them to determine that all communities funded through the RASP had access to the specified minimum level of services in all phases of the program.

TC relied on the reporting data provided by recipients to assess whether a reliable air network to remote communities was maintained. This data stated that over 100% of the scheduled routes were maintained over the course of RASP. This is a result of some of the funding being used for charter flights to previously non-identified remote communities, in addition to those which were originally identified.

Summary of RASP Success Factors and Lessons Learned

In the next few slides, we discuss practices that helped make the RASP a successful program, as well as the lessons learned that were identified. Below is summary of the practices that were deemed success factors for the RASP, as well lessons learned. Each statement is further explained on the following slides.

| Success Factors | Lesson Learned |

|---|---|

|

|

Success factors

Solid TC data and a definition of 'remote community', developed in consultation with PTs, contributed to successful program design and delivery.

While the RASP had to be developed quickly, TC had in place a strong foundation in the form of solid, in-depth data and a well-crafted working definition of a "remote community", which contributed to efficient and effective program design and delivery.

- Systems like ECATS provided useful information on carrier revenues as well as which carriers serviced which communities. PT's knowledge of carriers' operations in their jurisdictions varied - the Territories, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Quebec (which already had a similar program in place) had relatively strong understanding of carriers' operations in their jurisdictions, while Alberta (which ultimately did not participate in the RASP) and Saskatchewan lagged slightly behind in this regard. The availability of data meant that TC had a robust awareness of who to engage at the outset of the program, which contributed to efficient program delivery.

- According to program managers and PT partners, the definition of remote community as "communities that rely predominantly on air transportation to receive essential services" proved effective primarily because it allowed PTs the flexibility to determine which communities in their jurisdiction were eligible for RASP support. We also note that this definition was developed in consultation with some PTs.

Simplified contribution agreement design, and frequent and frank communication with stakeholders were cited as success factors for the RASP.

- The design of the RASP contribution agreements (CAs) were cited by both PT and TC interviewees as a key success factor for the program.

- "Light" in terms of requirements: PTs only had six commitments to meet.

- Flexibility and PT agency: under the shared governance approach adopted by the program, PTs had the responsibility for determining how to allocate RASP funds. The flexibility built into the CAs allowed PTs to exercise their agency more effectively, as they were able to make adjustments as realities changed. For example, PTs had the ability to adapt when a carrier temporarily opted out of the program. Similarly, PTs had the ability to add to the initial list of remote communities at the outset of the program. For example, in Phase 1, while 131 communities were initially identified (not including Alberta and Newfoundland-and-Labrador), ultimately 139 communities were serviced, as PTs added 8 more communities to the list. In Phase 2, 142 communities were serviced. This flexibility made the flow of the funds to the carriers more efficient and provided PTs with the ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

- Appropriate to the level of risk: since the CAs were with PTs, there was a level of confidence that the risk of not abiding by the CAs was low.

- TC's approach to communication was cited by both PT and TC interviewees as a key success factor and a best practice. Almost all interviewees noted that TC engaged in frequent, competent and frank communication with the PTs. This was particularly needed early in the pandemic when there was significant uncertainty about the future. By all accounts, the months preceding the August program announcement was the most challenging period for PTs and the carriers, and TC staff maintained proactive engagement, which helped calm anxious stakeholders.

Lesson learned

The flexibility built into the RASP and the effective communication approach adopted by TC program staff helped PTs and TC successfully navigate through challenges, such as the initial exclusion of charters or unforeseen events.

The RASP funding amount was based on scheduled passenger flights and did not originally account for charter flights. TC interviewees indicated that while the department had reliable data for scheduled passenger flights, data for charter operations was not readily available as it tends to be ad hoc in nature and numbers can vary widely. Given the priority to flow the money to intended recipients as quickly as possible, TC opted to conduct the necessary funding analysis based on data known to be reliable and readily available.

The initial exclusion of charters was one of the two areas of feedback we heard about consistently from PTs (the other one being the timing of the provision of funds). While PT interviewees stated that they would have appreciated increased funding to address charter company needs, we did not hear feedback, nor did we see evidence, that the initial exclusion of charters was a substantial challenge for PTs and had a negative impact on program outcomes. That's because PTs had ultimately the flexibility to determine how they allocated RASP funds, and they made use of that flexibility by funneling money to charter operations that they deemed essential to maintain the necessary air network to serve remote communities.

Ultimately, the program flexibility and the frank and frequent communication by TC program staff helped PTs and TC successfully navigate through challenges, such as the initial exclusion of charters or unforeseen events, like the 2021 federal election.

Conclusion

Interviews with PTs, carriers and TC staff indicate that the RASP was a much-needed temporary measure that delivered on its core objective of providing financial support to air carriers so that Canada could sustain a reliable air network for the movement of essential goods and services to its remote communities during the pandemic.

- No air carrier that received RASP funding went out of business

- Between July 2020 and December 2021, 100% of remote communities had retained essential air service for the movement of people and goods

The program was generally viewed by PTs as a well-designed initiative implemented effectively under challenging circumstances, with features such as more PT control over program delivery and streamlined contribution agreements identified as success factors. The concerted effort by TC program staff to maintain frequent and frank communication with stakeholders was identified as a best practice.

Funds getting to carriers in a timely manner, in particular during Phase 1, as well as the initial exclusion of charters from the program scope, were mentioned as challenges by PTs. That said, PTs had the flexibility to eventually fund charter operations, which some did. Overall, these were not characterized as major hurdles to the achievement program's key objectives.

The following lesson learned was identified:

- The flexibility built into the RASP and the effective communication approach adopted by TC program staff helped PTs and TC navigate through challenges such as the initial exclusion of charters and unforeseen events.

Appendix A: List of acronyms

- CEWS: Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy

- COVID: Coronavirus Disease

- ECATS: Electronic Collection of Air Transportation Statistics

- PT: Provinces and Territories

- RASP: Remote Air Services Program

- TC: Transport Canada