Evaluation report outlining results of the Evaluation of the Safety and Security Standby Services at Transport Canada.

On this page

Executive summary

The Review of Safety and Security Standby Services provides an overview and analysis of current standby practices in the regions and headquarters, including the level of need and the impacts on individuals performing standby duties. The review’s scope is limited to Standby Services in the Safety and Security Group and does not include those carried out by other Transport Canada groups, such as Programs.

Standby Services are defined as duties performed by Transport Canada employees who are designated to be available at a known telephone number during off-duty hours (weekdays between 16:00 and 08:00, and all weekend and holiday hours) at both headquarters and regions. Employees on standby field calls about concerns, issues or emergencies related to air, rail, marine, and dangerous goods transportation and, where necessary, they initiate appropriate response procedures. Calls originate from a variety of sources, including Transport Canada Emergency centres, HQ and regions, other government departments (e.g., RCMP, National Defense), the industry, the public, law enforcement, search and rescue organizations, Port Authorities, Marine Security Operations Centres, US government agencies, Canadian Air Transportation Security Authority, and the Transportation Safety Board.

What we found:

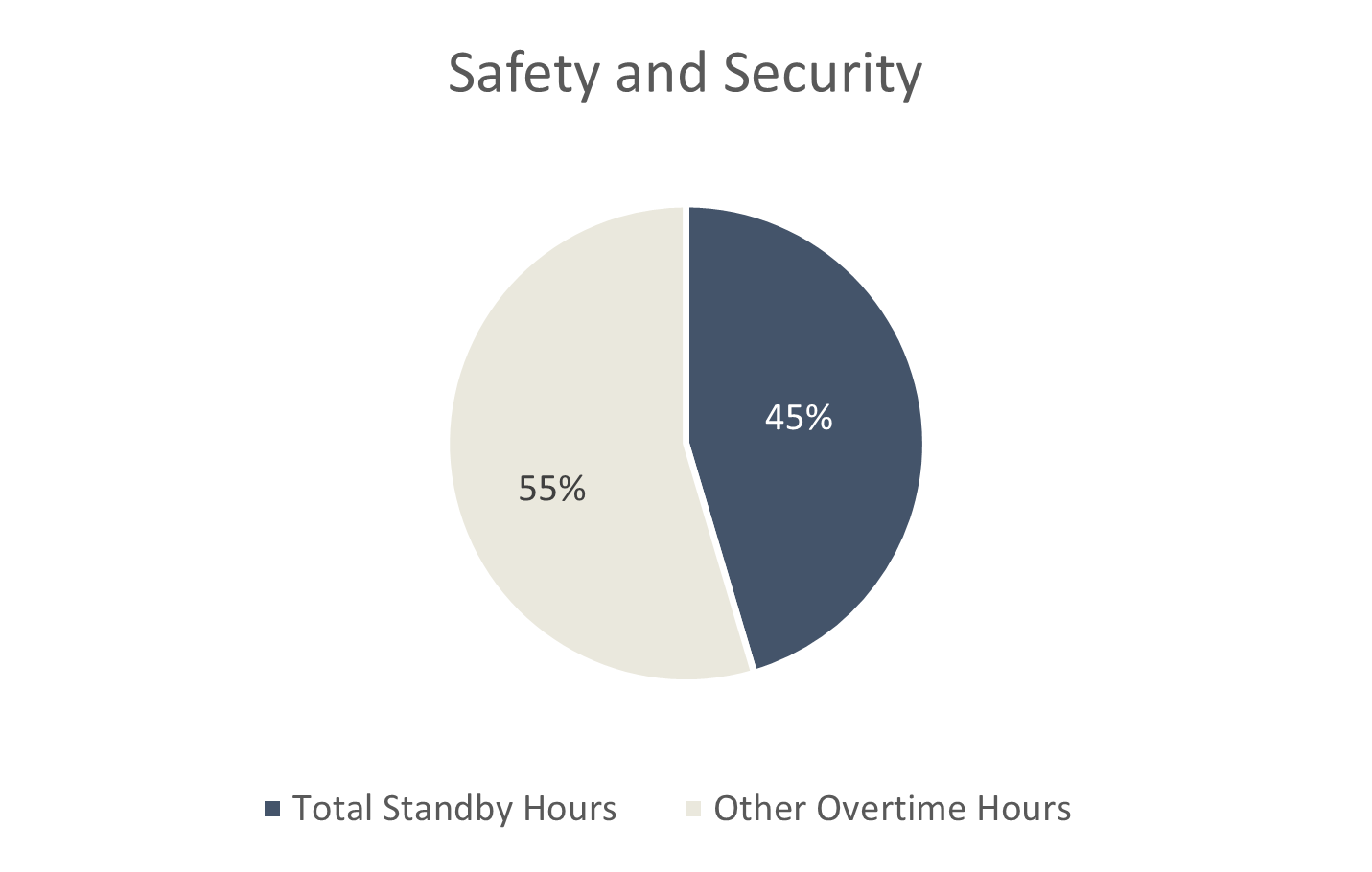

- There is an ongoing need for Standby Services in the Regions and headquarters. Approximately the same volume of notifications is sent in the off hours as during regular work hours. Furthermore, the overtime incurred for standby constitutes 45% of total overtime in the Safety and Security group. The need for Standby Services has been amplified by social media’s impact on the speed of communications, placing further pressure on those responsible for supplying, packaging, and moving information through the organization in the event of an incident in off-hours.

- As part of the 2013 Deficit Reduction Action Plan, Transport Canada made changes to Safety and Security Standby Services in regions and headquarters, including reduction of resources through the elimination of duty officer positions. Faced with the prospect of having to ensure standby capability with reduced resources, most modes/regions adjusted their approaches to standby based on their specific operating contexts. Today, Standby Services practices are rather inconsistent across modes and regions. These practices range from what we called structured standby to unstructured standby.

- Inconsistent standby practices have two key consequences:

- Uneven workload and compensation, leading to perceptions of unfairness.

- High and/or continual stress, leading to adverse impacts on some employees’ well-being.

- Some federal departments and agencies have off-hour environments and standby structures that are comparable to that of TC, and they also grapple with issues of consistency and well-being of individuals. The examination of these departments’ approaches offers useful insights and best practices, but we have not identified a radically different “silver bullet” model that TC can consider emulating.

Based on our findings, we recommend the following:

Transport Canada’s Safety and Security Group should:

Recommendation 1:

In the short-term, implement interim measures to address key risks identified in this review, namely perceptions of unfairness resulting from uneven workload and compensation, and high stress levels for some employees as a result of their standby duties.

Recommendation 2:

In the medium-term, develop and implement a comprehensive national standby policy. The policy development should be informed by all potential options while taking into account the different needs and operational contexts of modes and regions.

Recommendation 3:

Carry out a review 18 to 24 months after the launch of the new policy to ensure adequate and consistent implementation.

Introduction

Transport Canada’s (TC) Evaluation and Advisory Services (EAS) conducted a Review of Safety and Security Group’s Standby Services to provide answers to the following questions:

- What is the level of need for Standby Services in Safety and Security?

- What are current practices of Standby Services in modes, regions, and national headquarters?

- What are the key issues with respect to Standby Services in modes, regions, and national headquarters?

- What are the impacts on individuals performing standby duties?

The review was included in TC’s Five-Year Departmental Evaluation Plan for 2019-2020. The project was requested by the Intermodal Surface, Security and Emergency Preparedness (ISSEP) Directorate and is intended to respond to TC’s Safety and Security Management Committee’s (SSMC) need to better understand the current state of Standby Services.

About the Safety and Security Standby Services

Standby Services covered in this review are defined as those performed by TC employees in the Safety and Security Group who are designated to be available at a known telephone number during off-duty hours (weekdays between 16:00 to 08:00, and all weekend and holiday hours) at headquarters (HQ) and in the regions. Employees on standby duty field calls about concerns, issues, or emergencies related to air transportation, rail transportation, marine transportation, and transportation of dangerous goods and, where necessary, initiate appropriate response procedures.

When an incident occurs in the off-hours, the employee on standby typically receives a notification from a TC emergency centre or another sourceFootnote 1. TC operates three emergency centres:

- SITCEN serves as the department’s 24/7 reporting hub for internal and external stakeholders (Marine, Surface, Aviation, Transportation of Dangerous Goods, and Intelligence) as part of various regulatory requirements for transportation safety and security. As required through the Federal Emergency Response Plan (FERP), the SITCEN is the coordinating body for TC’s emergency response function to emergencies and crisis, ensuring timely information sharing for safety and security issues with key partners across the department, with federal partner operation centres, U.S. government counterparts, and with industry stakeholders.

- CANUTEC is the Canadian Transport Emergency Centre operated by the Transportation of Dangerous Goods (TDG) Directorate of TC. The Directorate’s overall mandate is to promote public safety in the transportation of dangerous goods by all modes. CANUTEC was established in 1979 and is one of the major safety programs that TC delivers to promote the safe movement of people and goods throughout Canada. It is a national advisory service that assists emergency response personnel in handling dangerous goods emergencies on a 24/7 basis. The emergency centre is staffed by bilingual scientists specializing in chemistry or a related field and trained in emergency response. The emergency response advisors are experienced in interpreting technical information from various scientific sources including Safety Data Sheets (SDS) in order to provide advice.

- AVOPS is TC’s Aviation Operations Centre and provides a physical and virtually enabled operations capability that operates around the clock (24 hours, 7 days a week) to monitor and respond to any occurrences in the National Civil Air Transportation System (NCATS). The program is the national reporting point for the Civil Aviation Directorate and CADORS (Civil Aviation Daily Occurrence Reporting System). AVOPS is TC’s national point of contact for civil aviation emergency management activities, NCATS disruptions or safety and security concerns, law enforcement activities and public safety concerns.

A notificationFootnote 2 can be in the form of a phone call, email, fax, and more, and its content can range from a cursory summary of a resolved incident to an emergency call about an ongoing incident. While some notifications are simply emails for information, others may require action, in which case the employee on standby will take various steps depending on the type of incident. The response procedures include but are not limited to gathering information (e.g., contacting industry or emergency responders for details of the incident), ensuring that appropriate people are informed (e.g., sharing information with emergency centres in HQ and with senior management), and ensuring that appropriate recommendations for mobilization of resources are made (e.g., sending an inspector on-site).

Logging standby activity

In modes/regions with scheduled standby, employees log their total hours spent on standby and hours spent physically responding to calls in the Leave and Extra Duty System (LEX), TC’s system for entering and tracking leave and extra duty. Overtime associated with standby can be split into two categories:

- Standby Hours - Refers to the time that employees are expected to be available in case of emergencies and is logged into LEX using the following codes: “064-Standby-normal schedule work-first rate” and “065-Standby-day rest/designated holiday-2nd rate”.

- Call Hours - Refers to the time that employees are actively responding to a call and are logged into LEX with the following codes: “010-Call In”Footnote 3 or “009-Callback”Footnote 4.

The above describes the generic aspects of standby services. Modes/regions vary in how they organize themselves to fulfil their standby responsibilities. A key objective of this review was to provide an overview and analysis of these various practices, which can be found in Section II: Current Safety and Security Standby Practices and Section III: Key Issues Regarding the Current Standby Practices in the Safety and Security Group.

About the review

Review scope

The scope of this review is limited to Standby Services in the Safety and Security Group and does not include other groups in TC that perform standby activities. Our review used a 2013 Deficit Reduction Action Plan (DRAP) initiative as a key reference point because this initiative introduced significant changes to Standby Services, which were limited to the Safety and Security group.

The Safety and Security programs covered by this review are:

- Marine Safety and Security (MSS)

- Civil Aviation

- Transportation of Dangerous Goods (TDG)

- Rail Safety

- Aviation Security

- Intermodal Surface, Security and Emergency Preparedness

The Safety and Security Group is organized slightly differently in the Regions. The Surface directorates encompass TDG and rail safety responsibilities, while Transportation Security and Emergency Preparedness (TSEP) teams have responsibilities related to aviation security, rail security and emergency preparedness. In this review, when we refer to Surface or TSEP, we are talking about teams in the regions.

TC’s Safety and Security Group also includes the Aircraft Services Directorate, which is responsible for the provision of aviation services in support of TC operations as well as those of other federal departments and agencies. Aircraft Services is excluded from this review as they are significantly different in structure and do not have standby.

Finally, we note that this review is not intended to be an assessment of SITCEN or other TC emergency centres. Our focus is to provide an overview and analysis of current standby practices in the regions and HQ, and we broach the SITCEN to the extent that it is relevant to the discussion of those practices.

Review methods

We relied on multiple lines of evidence to develop this report’s findings, including a database analysis, document review, and interviews with internal stakeholders and representatives from other government departments.

Data analysis

Information pertinent to Standby Services was extracted from a Business Intelligence (BI) Dashboard compiled by the Finance Group. This dashboard includes data on overtime and standby for 2017-2018 and 2018-2019.

We were provided with data on notifications between emergency centres (the Situation Centre [SITCEN], Aviation Operations [AVOPS], and the Canadian Transport Emergency Centre [CANUTEC]) and the relevant modes/regions, which are tracked through the Transport Canada Operations Management System (TCOMS). We analyzed data from these datasets to identify trends and irregularities.

We extracted a total of 340 data points including the number of hours on standby, the monetary value of those hours, the number of interactions between employees performing standby and emergency call centres, the type of overtime, the mode, the region, and the year.

Document review

We reviewed a range of documents to better understand how Standby Services are managed in each mode and region, including reporting templates, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), call logs, and examples of notifications from the SITCEN and other emergency centres. We reviewed available 2013 DRAP-related documents, including presentations to TC’s Executive Management Committee (TMX), risk analyses, and committee and working group documents. We also reviewed past internal audits which focused on overtime and standby in particular, including the 2006 and 2008 Audits of Overtime.

Data collection forms

We provided data collection forms to each region to gather information on Standby Services, including on how many individuals were on standby, their positions, approximate number of standby hours per week or month, relevant SOPs, and other internal documents such as call-back lists, templates, and rosters of standby employees.

Interviews

We conducted 84 internal interviewsFootnote 5 (54 of them in regions) with a total of 93 individuals at all levels of the organization, including inspectors, Remedial Measures Specialists, managers, chiefs, analysts, Directors, Regional Directors (RD), Modal Directors General, and Regional Directors General, covering all five TC regions and HQ. We organized interview responses by theme and coded them manually.

We also conducted eight scoping interviews at the planning phase of the review, in particular with employees who were involved in the 2013 DRAP initiative and who were able to provide historical information.

Comparison with other federal government departments

We conducted a comparison exercise to examine how other federal government departments and agencies (OGD) organized themselves to address issues or emergencies that occur outside the regular business hours. To determine which departments were suitable for inclusion in the comparison exercise, we deployed a scoping survey to 15 federal departments. Based on the survey results, we selected the following departments for the comparative review:

- Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

- Natural Resources Canada (NRCan)

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC)

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC)

- Public Safety Canada’s Government Operations Centre (GOC)Footnote 6

We used the following criteria to make our selection to ensure adequate and balanced coverage:

- location of standby/off-hours services (HQ, regions, or both)

- presence of an emergency call centre

- presence of formal (paid) standby arrangement

- at least one department with a shift-based arrangement

- availability of relevant studies, reviews, or audits

Following our selection, we conducted a total of 10 interviews with representatives from each department. The number of interviewees per department or agency is as follows:

- CBSA – 4 (2 in a group interview)

- RCMP – 3

- NRCan – 1

- IRCC – 3 (group interview)

- AAFC – 1

- GOC – 1

Considerations

Data consistency

The key indicators that track Standby Services (hours, costs, interactions, overtime in LEX) are not consistently recorded. This creates a challenge when trying to provide detailed comparisons of standby activity levels and overtime hours between modes and regions. Different operating environments can lead to varying data collection practices, but we expected to see more consistency across these key indicators.

There is also evidence that interactions, defined as any interaction between an emergency centre (SITCEN, CANUTEC, AVOPS) and regions/HQ related to an incident are often duplicated or triplicated. In keeping with their role as triage hubs, the emergency centres often forward information to relevant parties. Every interaction is counted separately, even if they relate to the same incident. This practice tends to inflate the number of interactions. As explained further in the report, we tried to counteract this by considering the number of interactions in conjunction with Call Hours and interview evidence to get a sense of the level of activity in off hours.

Data availability

TCOMS data begins in 2018 and the Standby BI Dashboard that presents LEX data only goes back to 2017-2018. We also had incomplete data for 2020-2021 since the fiscal year was not complete at the time of the analysis.

Despite this particular limitation, we had access to significant amounts of other data from the modes and regions as well as from the Finance Group (Overtime and Standby BI Dashboard), and we used multiple lines of evidence to draw conclusions with confidence.

Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+)

GBA+ is an analytical process used to assess how diverse groups of women, men, and non-binary people may experience policies, programs, and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences and recognizes the multiple identity factors that intersect to make an individual who they are. GBA+ takes into account the many other identifying factors, such as race, ethnicity, age, and mental or physical disabilityFootnote 7. The Directive on Results (2016) requires program officials and evaluators to include government-wide considerations, such as GBA+, where relevant, and requires the evaluators to plan evaluations to take those same considerations into account. To incorporate GBA+ into this review, we formulated GBA+ questions, following available guidance, and ensured that review methodologies, including interviews, saw equal representation from multiple population groups. The review did not collect gender disaggregated data.

Findings

In this section we present our findings about the need for Standby Services in the Safety and Security Group; the current practices of Standby Services in modes/regions; the key issues with respect to current practices; and the impacts on individuals performing standby duties.

Section I: The need for Standby Services

Finding 1: There is an ongoing need for Standby Services in the Safety and Security Group.

When presenting our analysis in this section, we use the following terminology:

- Interactions (or notifications): Any communication between an emergency centre (SITCEN, CANUTEC, AVOPS) and regions/HQ related to an incident. TCOMS uses the term “interactions” to denote communications between standby personnel and call centres; in this report “interactions” and “notifications” are used interchangeably.

- Standby Hours: Time that employees are expected to be available in case of emergencies (logged into LEX using the following codes: “064-Standby-normal schedule work-first rate” and “065-Standby-day rest/designated holiday-2nd rate”)

- Call Hours: Time that employees are actively responding to a call (logged into LEX with the following codes: “010-Call In”Footnote 8 or “009-Callback”Footnote 9)

- Total Standby Overtime: Sum of standby hours and call hours

Our analysis shows that there is an ongoing need for standby capability in the Safety and Security Group. Approximately the same volume of notifications is sent in the off-hours as during regular work hours (see Table 1 below). These interactions include phone calls, emails, fax, and more, and their content can range from a cursory summary of a resolved incident to an emergency call about an ongoing incident.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Work hours (08:00-16:00) |

51% | 49% | 51% |

|

Off-hours (16:00-08:00) |

49% | 51% | 49% |

Furthermore, standby hours constitute a sizeable portion (45%) of total overtime hours in the Safety and Security Group (see Graph 1 below).

Graph 1: Total standby hours vs other overtime hours in Safety and Security

(2017-2018 to 2019-2020)

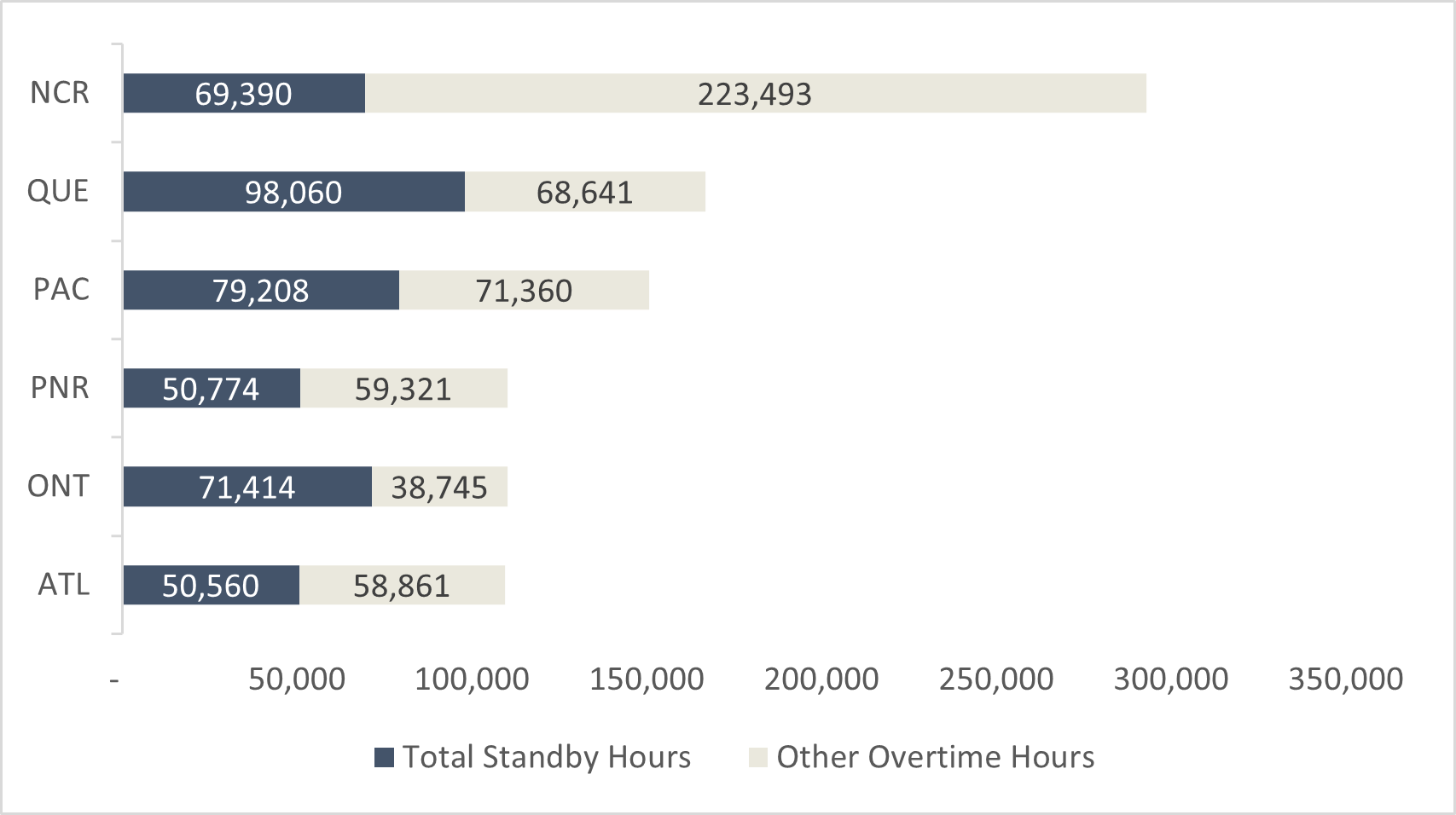

When broken down by region, Ontario has the highest proportion of total standby overtime hours in relation to total overtime hours (65%), followed by Quebec (59%) and Pacific (53%). Atlantic and PNR are both at 46%. However, Quebec has the highest number of standby hours with 98,060 followed by Pacific (74,208) and Ontario (71,414).

Graph 2: Total standby hours vs other overtime hours in Safety and Security, by region

(2017-2018 to 2019-2020)

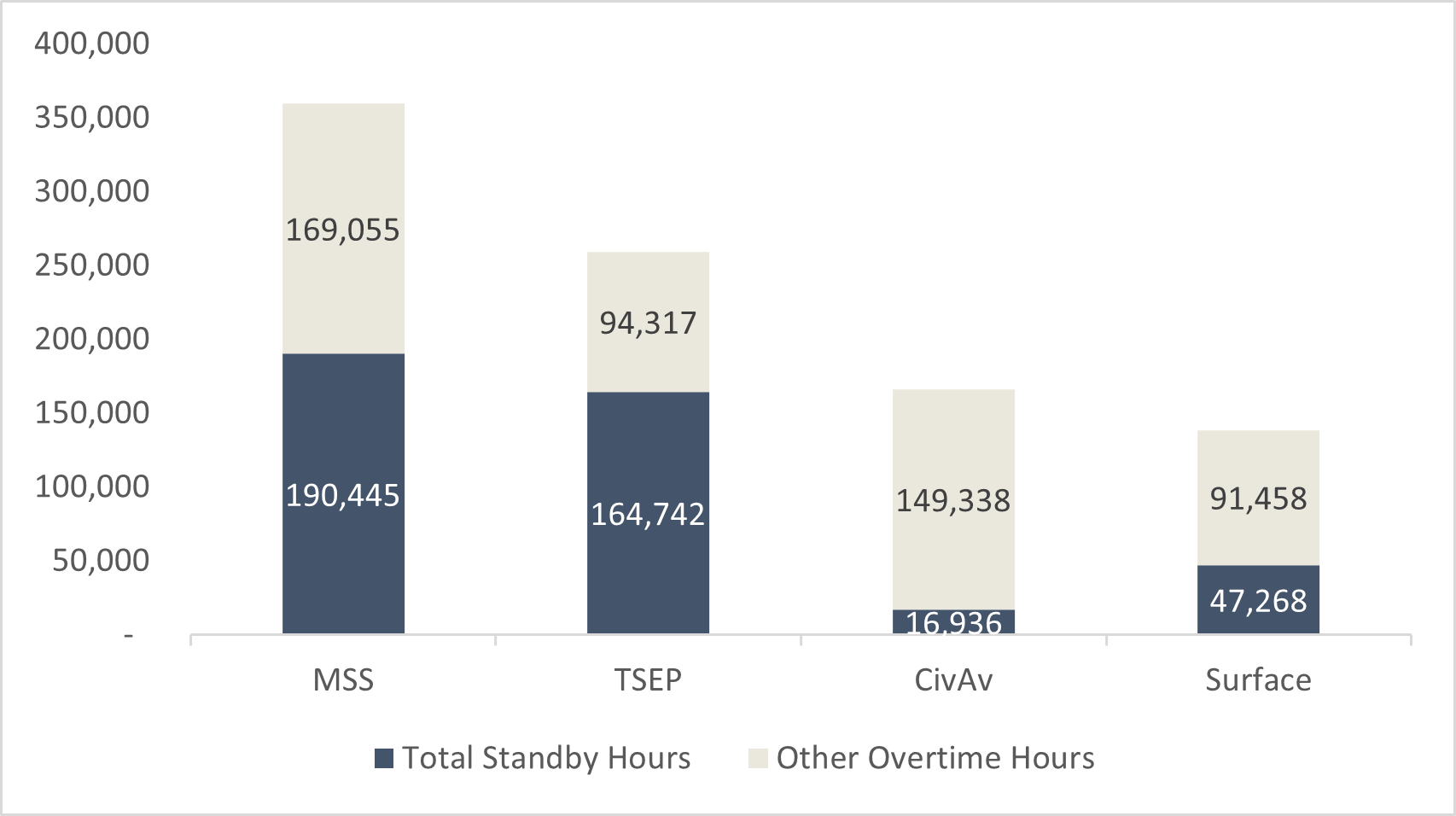

When broken down by mode, ISSEP (which we refer to as TSEP in the regions) has the highest proportion of total standby overtime hours in relation to total overtime hours (64%), followed by MSS with 53% and Surface with 34%. However, MSS has the highest number of total standby overtime hours with 190,445.

Graph 3: Total standby hours vs other overtime hours in Safety and Security, by mode

(2017-2018 to 2019-2020)

Thus far, we have provided a snapshot of how busy the modes/regions are in the off hours by comparing:

- the number of interactions in the off hours to regular work hours (table 1)

- total standby overtime to other overtime (graphs 1-3)

To refine our analysis, we also examined ‘call hours’, which refer to the overtime that employees actively spend responding to calls. However, rather than analyzing call hours in isolation, we examined them alongside the number of total interactions because counting only call hours can underestimate the level of activity in the off hours; it only gives us the minimum amount of hours spent responding to incidents and does not capture the hours worked by EXs or employees who do not claim overtime for their work. Examining total interactions together with call hours can mitigate this shortcoming since interactions capture all notifications sent to or received from modes/regions, including through EXsFootnote 10. (Incidentally, counting interactions alone can overestimate the level of activity in the off hours because not every interaction generates call hours; some interactions are dealt with the following day during regular work hours). Examining call hours and interactions together and triangulating the results with interview evidence allowed us to provide a more accurate estimate of the level of standby activity in the off hours.

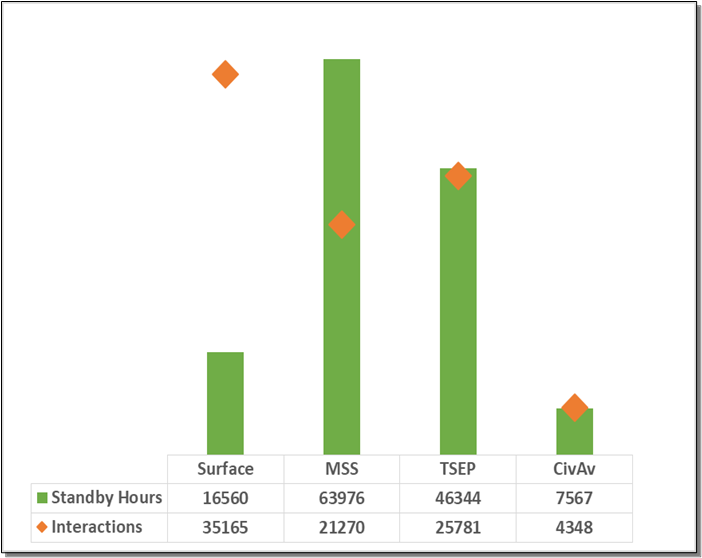

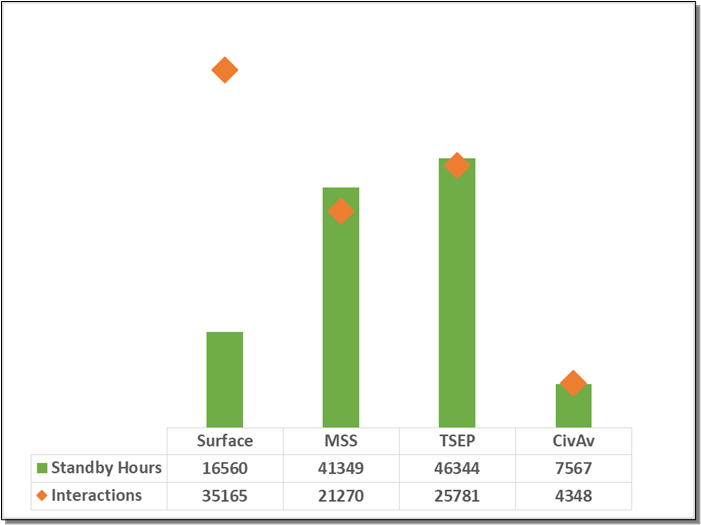

A good example is the Surface mode in the regions (Rail Safety and TDG) which as a whole has the lowest number of call hours even though it accounts for the highest number of interactions among all the modes (see Graph 4)Footnote 11.

Graph 4: Volume of interactions and call hours, by mode (2019)

Initially this would suggest that Surface is either faster at managing incidents (thus fewer call hours) or they wait until normal office hours to respond. However, neither is the case; rather, the numbers alone fail to capture some of the off-hour activity. In Surface, Regional Directors and managers are responsible for standby. According to interviews, because EXs do not claim overtime, and because some teams have a culture of not always logging standby overtime by those below the EX level, part of Surface’s standby activity is not captured in any system. Therefore, Surface is actually busier in the off hours than the data alone suggests.

Below are other highlights from our analysis of various modes’ level of activity in the off hours.

Marine Safety and Security (MSS)

MSS has the highest volume of total standby overtime (as shown in Graph 3) in Safety and Security. Total standby overtime accounts for roughly half of MSS’ total overtime.

In select regions, MSS performs Port Warden (or Marine Cargo) Services to ensure that higher-risk marine cargo is safely loaded and stowed onboard vesselsFootnote 12. Due to their recurring nature and the fact that the private benefit associated with these services considerably outweighs the public benefit, Port Warden services are partially cost-recoverable. To ensure that Port Warden activities did not skew our analysis, we compared MSS to the other modes both with and without Port Warden duties included. When Port Warden duties were included, we found that MSS had the highest amount of call hours (see graph 4 above) and standby hours (see Graph 5 below).

Graph 5: Volume of interactions and standby hours, by mode (2019)

When Port Warden is excluded from the analysis, we found MSS to be comparable to TSEP (which includes Aviation Security, Rail Security, and regional Emergency Preparedness) in terms of the level of activity (see Graphs 6 and 7 below). This is in line with what we expected to find given the interview evidence and considering that TSEP and MSS have similar standby practices.

Graph 6: Volume of interactions and call hours*, by mode (2019)

*Call hours in MSS recorded under “Port Warden” are excluded in this graph.

Graph 7: Volume of interactions and standby hours*, by mode (2019)

*Standby hours in MSS recorded under “Port Warden” are excluded in this graph.

Civil Aviation

AVOPS, the national point of contact for civil aviation emergency management activities, receives and responds to all Civil Aviation incidents. This centralized approach generates fewer interactions and standby hours compared to other modes (as seen in Graph 7 above). However, interviewees noted that AVOPS processes more interactions and are busier than the data alone suggests. AVOPS staff estimate that the unit only reports 5% of the total annual interactions due to a lack of resources and does not always log interactions in TCOMS in a timely manner due to their heavy workload. They also note that there are approximately 13,000 NAV CANADA Aviation Occurrence Reports every year which are not captured in TCOMS. Finally, the actual amount of standby work being performed in Civil Aviation may be under-represented in graph 7, since the RDCAs who are responsible for standby in the regions are not entitled to overtime. That said, we were informed that the RDCAs do not receive many calls during the off-hours, therefore under-representation is not significant.

In conclusion, TC business does not stop at 16:00 EST and noteworthy activity occurs in the off hours. While the 2013 DRAP exercise took away standby resources in some modes, standby needs continued and, in some cases increased, leaving units scrambling to find ways to fulfil standby obligations. In Section II: Current Safety and Security Standby Practices we discuss how various modes and regions have organized themselves to meet the demand for Standby Services.

Finding 2: The pressure to react to events in off hours in a timely and effective manner and to move information quickly through the organization at times strains the capacity of current standby arrangements.

TC’s role when an incident occurs can be split into two main parts: managing the incident and managing the flow of information about the incident. It is impossible to predict when an incident will occur or how serious it will be, and all modes and regions must be prepared to respond efficiently and effectively at any given time. A delayed or substandard response to an incident can have significant consequences for the safety and security of Canadians and TC’s reputation.

Today, information moves extremely fast. Social media has considerably decreased the amount of time between when an incident occurs and the first media reports. When an incident occurs, senior management is often already aware and will request an update before the region receives a notification from an emergency centre. Staying on top of events in the age of social media is therefore more challenging than it has ever been.

When faced with an incident that is likely to attract media attention, the need for quick and accurate information can put significant pressure on those responsible for supplying, packaging, and moving information through the organizationFootnote 13. A good example is the Surface directorate in PNR. While its standby resources were reduced following the DRAP exercise, the directorate has had to contend with nine significant derailments since 2013 and four incidents involving six railway employee fatalities since 2017. The responsibilities associated with managing the incidents, obtaining information regarding the incidents, and briefing up in a timely manner have put significant pressure on the directorate’s limited standby capacity. The directorate managed to fulfil these duties primarily because of staff’s dedication and willingness to answer their phones at all times, on the weekends and at night. Since the spring of 2020, PNR Surface has resumed paying standby to cover TDG incidents.

Another area of concern is how incident information intended for senior management is packaged. It is increasingly vital to get accurate information into the hands of senior management as quickly as possible so that they understand what is going on and are ready for various information requests, for example by the Minister’s office or the media. We received feedback that reports provided to senior management do not always meet their needs in terms of clarity and level of detail. Several interviewees noted the necessity for plain language and reporting templates while striving to meet the needs of two types of audiences: senior management and technical.

Given the high demand for information during standby shifts, respondents also suggested reviewing distribution lists and finding ways to minimize the amount of information exchanged and to avoid duplication. Finally, the exchange and management of information present a challenge in terms of both the need for immediate information from multiple internal stakeholders during standby and the amount of post-event administrative work that is required. This at times spills over and affects day duties of Standby Duty Officers.

Regions – SITCEN interactions

Regarding regions’ interactions with the SITCEN, we found that there was a lack of clear understanding about the role and mandate of the SITCEN. Some interviewees noted that it would be beneficial if more information was shared about what SITCEN does and does not do.

Most interviewees viewed the SITCEN as a conduit for information rather than the information source. Some shared examples where a confusing SITCEN notification could have benefited from technical expertise, or where specific knowledge of a mode could have helped triage a notification to a more qualified regional recipient. Others in the regions recognized high turnover at the SITCEN and that there are sometimes changes in the quality of SITCEN reports while a new employee becomes accustomed to the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs). Quite a few interviewees noted that the SITCEN concept has worked well as a single notifications hub, but that the line of communication can be jumbled or delayed when they are not looped into an incident.

Section II: Current Safety and Security standby practices

Finding 3: Current standby practices are inconsistent between modes and across regions within the same mode.

In 2013, as part of DRAP, TC made comprehensive changes to the structure and performance of Safety and Security Standby Services.

This initiative consisted of three parts:

- Reduction of standby services costs in headquarters for four Safety and Security Directorates (i.e., Civil Aviation, Surface and Intermodal Security, Marine Security and Aviation Security).

- Rationalization of standby services in all five regions through elimination of duty officer positions and reduction of standby hours.

- Identification of options to streamline HQ Emergency Centres and transform service delivery.

The initiative introduced significant changes to Standby Services, including eliminating duty officer positions in some modes (e.g., transfer of the duty officer functions to SITCEN from three areas: Surface and Intermodal Security, Aviation Security, Marine Security) and shifting standby responsibilities to regional directors. However, indications are these changes were not communicated as effectively as they could have been to the regions, and directions on implementation were vague. In addition, a review of the initiative that was supposed to take place 18 months after implementation began was never carried out.

Ineffectual communication during the roll-out, lack of a planned review, and above all the continued need for standby capability while standby resources were reduced, led the modes/regions to adjust their practices based on their specific operational contextFootnote 14. Standby practices thus began morphing into the various forms that we see today across most modes and regions.

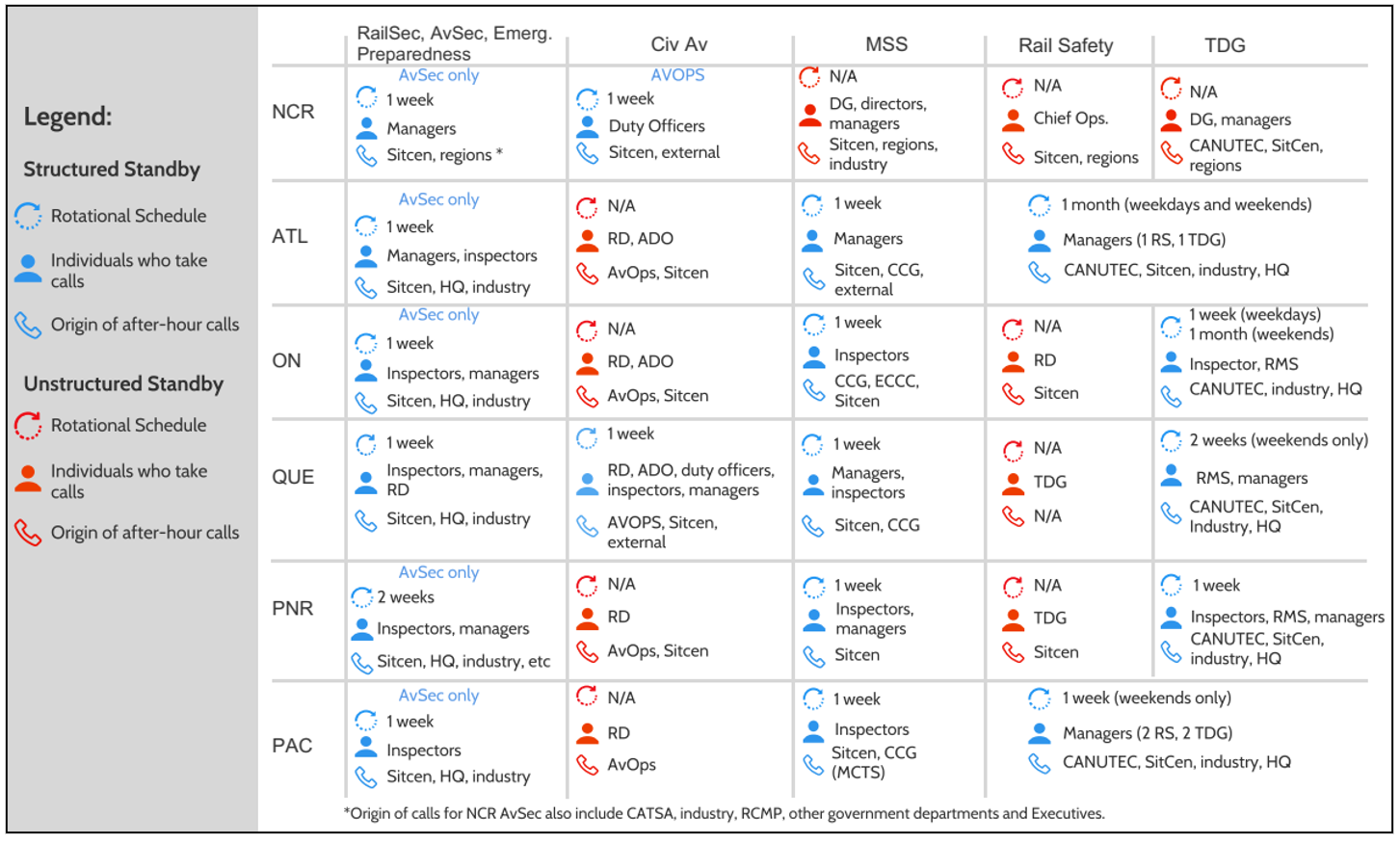

Table 2 below provides a snapshot of the current standby approaches in Safety and Security.

Table 2: Overview of current Safety and Security standby practices

Overview of current Safety and Security standby practices

National Capital Region

Aviation Security (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Managers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN and regions (note: origin of calls for NCR for Aviation Security include CATSA, RCMP, and other government departments and executives)

Civil Aviation (AVOPS) (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Duty Officers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN and external

Marine Safety and Security (MSS) (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- DGs, directors, managers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, regions, industry

Rail Safety (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- Chief, Operations takes incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, regions

Transportation of Dangerous Goods (TDG) (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- DG, managers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: CANUTEC, SITCEN, regions

Atlantic Region

Aviation Security (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Managers and inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, HQ, industry

Civil Aviation (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- RD and ADO take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: AVOPS. SITCEN

MSS (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- managers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, CCG, external

Rail Safety and TDG (structured standby)

- Rotation: monthly (weekdays and weekends)

- Managers (1 RS, 1 TDG) take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, HQ, industry

Ontario Region

Aviation Security (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Managers and inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, HQ, industry

Civil Aviation (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- RD and ADO take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: AVOPS, SITCEN

MSS (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: CCG, ECCC, SITCEN

Rail Safety (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- RD takes incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN

TDG (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly (weekdays); monthly (weekends)

- Inspectors, RMS take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: CANUTEC, industry, HQ

Quebec Region

AVSEC, Rail Security, Emergency Preparedness (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Managers, inspectors, and RD take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, HQ, industry

Civil Aviation (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- RD, ADO, duty officers, inspectors, and managers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: AVOPS, SITCEN, external

MSS (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- managers and inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, CCG

Rail Safety (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- TDG takes incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: not applicable

TDG (structured standby)

- Rotation: 2 weeks (weekends only)

- RMS, managers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: CANUTEC, SITCEN, industry, HQ

Prairie and Northern Region

Aviation Security (structured standby)

- Rotation: 2 weeks

- Managers and inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, HQ, industry, etc.

Civil Aviation (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- RD takes incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: AVOPS, SITCEN

MSS (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Managers and inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN

Rail Safety (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- TDG takes incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN

TDG (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Inspectors, RMS, managers take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: CANUTEC, SITCEN, industry, HQ

Pacific Region

Aviation Security (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, HQ, industry

Civil Aviation (unstructured standby)

- Rotation: not applicable

- RD takes incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: AVOPS

MSS (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly

- Inspectors take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: SITCEN, CCG (MCTS)

Rail Safety and TDG (structured standby)

- Rotation: weekly (weekends only)

- Managers (2 Rail Safety, 2 TDG) take incoming after-hour calls

- Sources of calls: CANUTEC, SITCEN, industry, HQ

Note 1: These practices reflect the standby environment in summer 2020 when we conducted our interviews. Some changes have taken place since. For example, Quebec region TDG now has structured standby on weekends and weekdays.

Note 2: There is a second layer of regional engagement performed by the Regional Directors, which can involve developing the initial response to an incident (where there is no formal standby structure), managing the incident with their management team, and being the point of contact along with their HQ functional colleagues; the chart does not include this type of engagement by the Regional Directors.

Modes and regions have adapted their services based on the number of calls that they receive, incidents they manage, their in-house capacity to fill a rotation, and their budget. Across the same mode, some regions have implemented standby on weekends only, where inspectors are on a set rotation while managers are generally available during the week, claiming only call-back and call-in hours in case of an incident. Most commonly, standby duty inspectors are on weekly rotations, but the number of individuals on rotation and the frequency of their shifts vary across regions and modes. In short, current standby practices vary between what we called structured standby and unstructured standby.

- By ‘structured standby’ we mean there is an established rotation system with duty inspectors performing standby and being responsible for any accompanying reports, interactions, or notifications. This includes being paid for standby services and associated call-in and call-back as per their relevant collective agreements.

- By ‘unstructured standby’ we mean staff who are available on an as-needed basis but who do not log overtime in LEX as ‘standby’. The most they may log is call-in or call-back. In the regions, these tend to be managers and sometimes inspectors. The key characteristic of unstructured standby is that it relies quite a bit on employees’ good graces – their willingness to answer their phones at all times of the weekend or night – to make the system work. This is indicative of unpaid standby.

MSS has the most consistent, decentralized, and structured approach to standby amongst all modes. Every region operates on a weekly rotation, covering both weekdays and weekends, with a staff roster of between 6 and 12 inspectors and managers. The notable exception is the National Capital Region (NCR) which has less structured standby. Instead, the NCR has separate call lists – two for Marine Safety and one for Marine Security – which, if required, the SITCEN will filter through until they reach someone.

In the regions, teams responsible for Aviation Security, Rail Security, and Emergency Preparedness typically share standby dutiesFootnote 15. Aviation Security has structured standby in all regions with rotations ranging from 6 to 11 duty inspectors. On the other hand, when a Rail Security incident occurs, the call usually goes to an on-duty Aviation Security officer who will then try to reach an off-duty Rail Security inspector or manager. This arrangement has worked up to present since there is a relatively low number of emergency callsFootnote 16 involving Rail Security.

Of all the modes, Surface in the regions (Rail Safety and TDG) have the widest variety of regional standby practices. Ontario, Quebec, and PNR rely on TDG officers/inspectors to cover standby during weekdays, but Atlantic and Pacific divide those responsibilities evenly between Rail Safety and TDG, answering each other’s calls on rotation (e.g., Rail Safety manages calls for one week and TDG manages calls for the next week). PNR and Atlantic have structured standby for both weekdays and weekends, but PNR’s standby is covered by TDG inspectors/Remedial Measures Specialists/managers while ATL’s standby is shared between Rail Safety and TDG (on rotation). In Pacific region, Rail Safety and TDG share structured standby on weekends only; if a Surface incident happens during a weekday, Pacific’s Regional Director will answer by default.

The only mode which has maintained its structure since the 2013 DRAP decision is Civil Aviation, where standby duties have been centralized within Aviation Operations (AVOPS) in the NCRFootnote 17. Quebec Region reinstated Duty Officers in 2020 in response to the strain on the EXs. The other regions have no regional duty inspectors but officers in AVOPS and NCR staff in Civil Aviation operate as standby duty inspectors when needed.

Finding 4: Standby data is not tracked consistently.

We found that inconsistent data entry and system limitations result in an incomplete and inaccurate picture of standby needs and application across the country.

Logging of overtime

Employees log all overtime, including overtime related to Standby Services, into the HR LEX system. This permits managers to review and approve overtime, track how much overtime is being claimed and for what purposes, and the total overtime costs. However, we identified inconsistencies and missing information through our data analysis and interview evidence.

The inconsistencies revolve around two key issues: what overtime is claimed and how it is logged.

Interviews indicated that employees do not claim all their standby overtime, particularly in regions and modes that rely on unstructured standby. In cases where employees do claim overtime, the level of detail that they log varies; some entries reflect the exact length of time spent responding to the call, while others show how much that time equals in overtime pay. For example, for a five-minute call, some may enter five minutes while others may enter one hour as the overtime pay equivalent. Ultimately, both employees are still paid an hour according to the collective agreements, but the data does not tell us how much actual time is spent responding to an incident.

EXs are not represented in the LEX data since they are not entitled to overtime. This also skews the actual standby hours in modes/regions where EXs often respond to calls.

Tracking of interactions

All interactions between the emergency centres and regions are recorded in TCOMS, but the level of detail in these records varies both within and across emergency centres. For example, some entries do not specify which region was being contacted, while other entries are listed as low priority and never entered in the system due to capacity issues.

Similar to LEX, TCOMS has system limitations. In addition to inconsistent reporting, the data recording the number of interactions does not specify whether those calls took place during standby hours or the regular workday. This would presumably make assigning resources more difficult.

Complete, accurate, and comparable data is essential for TC to make informed decisions on how to manage standby resources. Any consideration of a new national standby approach or policy, which is our main recommendation in this report, should therefore take into account the issue of inconsistent or incomplete data related to standby.

Section III: Key issues regarding the current Safety and Security standby practices

Finding 5: Inconsistent standby approaches result in:

- Uneven workload and compensation leading to perceptions of unfairness; and,

- Elevated and/or continual stress levels leading to adverse impacts on some employees’ well-being.

Uneven workload and compensation

Forty-three interviewees gave a response that referenced either unfair or unpaid standby practices. In our methodology, if one interviewee stated that they or their colleagues performed unpaid standby, we identified their team as having unpaid standby. The same method was followed for call hours not claimed as overtime.

We found that a lack of standardization and transparency encourages groups to believe that other modes/regions are operating with more support. After DRAP, units had to figure out how to provide the same coverage with fewer resources. The varying operational environments between modes and between regions within the same mode led to different approaches being put in place. Units that continued to operate with reduced or no standby resources indicated that they felt ignored; many interviewees noted that it was fundamentally unfair when one group received compensation for a service that was purportedly eliminated while another group continued to essentially work for free. Below is a sample of what we heard.

“We also recently found out that some regions are still paying standby during the week which goes against the national procedures.”

“We were told to stop standby and people just continued to do it.”

“They have someone on standby all the time, so they’re not actually following the procedure that was set out. […] They don’t get any more calls than we do, but they’re actually paid for standby.”

“Would be nice if we had the same level of standby services in all modes. [Some teams] don’t have a formal standby arrangement. We’re basically asking the managers there to work after hours for free.”

“I’d like all of TC to see what standby looks like in all the modes. Why do we treat some modes differently than others in terms of budget or call statistics?”

One of the benefits of structured standby is that expectations are well-defined and understood: the employee must be available, will be compensated, and should return to work as quickly as possible if called in. When a group operates in an unstructured manner, the rules are much less clear. Can an employee who is not technically on call leave town? Do they need to be in an area where there is cell phone service? Do they need to carry their phone at all times?

A number of units have expressed a reliance on the “goodwill” of their employees (specifically at the manager and inspector level), meaning some current standby structures rely on willing individuals who are not formally on standby to answer calls after hours or on weekends. For example, an EX receiving a call while on standby may call an off-duty manager or an inspector for their technical expertise, or an inspector on standby may call an off-duty manager for direction or delegation authority. After a while, this availability becomes an expectation. In one region, one manager took all after-hour calls in his area for a seven-year period. Of the 43 interviewees who commented on unpaid standby practices, nearly half (21) noted that the current system relies on employees’ good graces to work effectively.

Relying on goodwill does not always imply that the employee is performing unpaid standby. However, it does suggest a few risks to the standby system. For one, some off-duty employees may be filling the same role and have a similar workload as an employee officially on paid standby. This can create a perception of unfair standby practices. There is also a small risk that TC may not be able to manage an incident effectively if none of its off-duty employees answer the phone.

For teams that don’t have structured standby, logging overtime is the typical fallback. It ensures that employees are still compensated for their time responding to incidents, even if not for their time spent being generally available during off-hours. However, this is not always the practice. Individuals do not always log overtime for a variety of reasons, such as team culture – the desire to be a “team player” or a “helpful employee” – or if the call was short or the question was quick to answer.

Collective Agreement crosswalk

The Collective Agreements stipulate how much should be paid per hour of standby worked. We reviewed standby requirements under the Collective Agreements for five classifications: PA, TC, SP, EC, and AO. All five included the same three requirements:

- That the employee be available by phone

- That the employee return to work if required

- In designating employees for standby, the employer provide the equitable distribution of standby duties

The Collective Agreements state that the employee on standby should be compensated for their time, but there are indications that while standby work occurs, it is not consistently paid in some groups (see Table 3 below). Inconsistent compensation for similar responsibilities and work feeds into perceptions of unfairness.

We note that Table 3 provides a snapshot as of 2019. A number of directorates in regions have since resumed paying for standby, notably Quebec Civil Aviation, PNR Surface, and Quebec TDG.

| Surface | MSS | CivAv | Rail Security | Aviation Security | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATL | Paid Standby | Paid Standby | EXs Standby | Paid Standby | ||

| QUE | Unpaid StandbyFootnote * | Paid Standby | EXs StandbyFootnote *** | Unpaid Standby | Unpaid Standby | |

| ON | Paid Standby | Paid Standby | EXs Standby | Unpaid Standby | Paid Standby | |

| PNR | Unpaid StandbyFootnote ** | Paid Standby | EXs Standby | Unpaid Standby | Paid Standby | |

| PAC | Call hours not claimed | Paid Standby | EXs Standby | Unpaid Standby | Paid Standby | |

| NCR |

Rail Safety Call hours not claimed |

TDG Call hours not claimed |

Unpaid Standby | Paid Standby | EXs Standby | Paid Standby |

Impacts on individuals

Our primary source of information for assessing the impact of standby on individuals was interviews. Of the 93 interviewees, 37Footnote 18 provided relatively clear responses when asked if being on standby had an impact on their level of stress or had an effect on their work/life balance. Twenty-seven felt that being on standby was a source of stress. Six gave mixed responses (e.g., it did not cause them stress personally but they were aware of impacts on colleagues). Eight felt that Standby Services were not a source of stress or that the stress was manageable.

Key stress factors mentioned were workload (in particular, during significant incidents), the frequency and nature of phone calls, impacts on sleep, the feeling of always having to be “on”, and the inability to make plans with family.

Fourteen interviewees specified which positions, in their opinion, had the heaviest workload and, as a result, high levels of stress. Of those, nine felt that the heaviest burden fell on EXs. One region has reinstated duty officers in one mode during the off-hours in 2020 after recognizing the significant strain on EXs. Responses from MSS were the exception where the burden is felt most heavily by inspectors and managers. This is likely due to MSS’ structured approach to standby which rotates exclusively between inspectors and managers in five regions, excluding the NCR.

“There is absolutely a different level of impact on the RDs with standby [officers] vs those without standby officers. They are the ones who receive the calls all the time and it is extremely stressful.”

“I would say the biggest toll is on the RDs. There is a big toll on the work-life balance. From an RD perspective […] it is expected that they will be available at all times… Being on leave is the only way to take a mental break for an RD. I don’t think it is a sustainable expectation.”

The number of calls that a mode/region receives or the nature of these calls (for example, usual operations vs. a pollution incident) are factors when discussing stress. Some interviewees shared stories of colleagues who had responded to traumatic events and were no longer willing to volunteer for standby rotation because of the emotional impact. That said, some other interviewees indicated that they enjoyed the professional challenge that these incidents can generate.

The impact on sleep is another stress factor. Even if a mode operates on a well-populated rotation schedule and receives a manageable number of notifications, late-night calls inevitably impact sleep. Being woken up to respond to an incident takes a toll on mental health and can affect performance during regular office hours the following day. Even if a call lasts only a few minutes, getting back to sleep can be challenging. It results in tired, stressed employees who cannot fully disconnect from their jobs. Responding to a call in the middle of the night does not always end with a quick answer; standby officers may need to conduct analysis, write reports, and contact stakeholders.

“The most important impact is on sleep. If you respond to something in the middle of the night, the adrenaline kicks in and you’re not getting back to sleep.”

“It takes its toll on mental health. Whether it’s shift work or being called twice in one night and have to show up for work the following day. You get tired. If it happens once you can catch up, but over time it takes its toll.”

Being unable to unplug or the feeling of always having to be “on” was one of the most frequently and emphatically mentioned stressors in our interviews. For modes/regions without structured standby, calls go to employees who are expected to answer despite being off duty. Interviews showed that this feeling of having to be continually available has a cumulative effect on an individual’s stress levels. Given that standby work can also carry over into the following workday, it forces the employee to balance standby responsibilities with day tasks. Several interviewees pointed out that this was manageable if it happened once in a while but repeat occurrences could become problematic.

The factors listed above can result in continual and elevated individual stress levels, on occasion leading to burnout and extended leave. We heard of instances of this occurring, with off-hour workloads and stress specifically identified as causes.

Impacts to the organization were also reported. For example, there are cascading effects in a unit if an EX or manager goes on extended leave. In these cases, someone else has to step in and assume their responsibilities. Moreover, stress levels associated with EX positions in effect make these jobs less appealing and can constitute a disincentive for managers to join the executive ranks.

Other considerations

Reliance on key individuals

The current standby approaches require significant competence of and commitment by those few key employees who are at the intersection of ‘operational’ and ‘information flow’ needs when an incident occurs in the off hours. The necessary skillset for those individuals includes the ability to assimilate a significant amount of information quickly, to understand the environment (operational, political, etc.), to break down what is happening effectively, and to be a great communicator. The standby system is extremely reliant on these few individuals, which in effect renders the system vulnerable in cases where they may be unavailable or if they leave their positions. Interviews show that there are no easy fixes since it is not simply a question of offering more training to employees. As one senior executive told us, “Some people have it and get it, some people don’t.” Any future work on addressing standby at TC may need to take into account this particular vulnerability to the system.

COVID-19 impacts and GBA+

We asked interviewees if the pandemic had any impacts on standby duties. No impacts were identified. Some interviewees used this question to emphasize that being on standby has always meant working remotely, which requires the appropriate tools.

The review also considered gender imbalance and other GBA+ considerations in the standby context. We formulated GBA+ questions following Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) guidance and sought equal representation from multiple population groups. Our collected data was not gender disaggregated. We also consulted with departmental experts on GBA+ who indicated potential areas where gender could impact who applies for positions with standby requirements.

For example, seeing “mandatory standby” as a requirement on a job poster may be interpreted by some as “women need not apply.” Since women are traditionally the family caregivers it could be more difficult to find childcare on short notice. A 2020 GBA+ Report produced by TC labels this as the “myth of the unencumbered worker”Footnote 19. This report goes on to say that vague wording on job posters in respect to overtime and travel prevents candidates from knowing the exact time commitments associated with the position and discourages them from applying. It is challenging to prove this theory without interviewing all those who did not apply and asking whether this was the main deterrent. Instead, we asked our interviewees whether they know any colleagues who turned down standby responsibilities because of the extra hours. Of the few who addressed this question, the answer was no.

Another consideration brought up by Departmental GBA+ experts were rural employees who live in remote communities and commute into TC offices or to inspection sites. Women and some minority groups may not feel comfortable commuting in the middle of the night or attending an isolated inspection site. Our interviewees did not mention this as an issue, however that does not rule out the possibility that these concerns exist and have prevented some from applying for positions with standby.

Section IV: Standby best practices

In part due to different operating and regulatory contexts and in part due to the absence of a national approach for Standby Services, many teams have developed best practices to better address their operational needs.

Below is a summary based on document review and interview evidence. This summary is not exhaustive; there may be some groups that are performing these best practices but are not mentioned below. We also note that some of the best practices which work well for certain groups may not work well for others, therefore they should not be viewed as one-size-fits-all solutions.

Training and knowledge sharing

Some groups like TSEP Atlantic, TDG PNR, and MSS Quebec organize regular duty inspector review sessions to discuss recent incidents. This exercise is particularly useful for groups with a rotation of duty inspectors so that those off shift at the time of the incident can benefit from the experience.

These sessions are also great opportunities to update group procedures, although some teams find it hard to get everyone together regularly.

Some modes also organize larger, less frequent sessions to discuss their incident response procedures and any updates that may be necessary. These sessions are also opportunities to facilitate training and share experiences.

Supporting documentation and tools

Groups with duty inspector rotations have various best practices in place to help with internal organization. Some teams use regularly updated contact sheets to let their group and SITCEN know who is on shift and when. MSS Atlantic, for example, maintains a shift schedule, a list of duty inspectors, their phone numbers, and backup phone numbers. This document includes basic operating procedures outlining the duty inspector’s responsibilities during an incident.

Other groups have reduced the reliance on contact sheets by setting up a single common phone number. TSEP in Pacific, for example, automatically forwards calls to whomever is on duty. This makes it easier for call centres like SITCEN or CANUTEC to know which number to use since it never changes, no matter who is on duty.

Some groups also log calls and incidents in RDIMS. This not only helps teams keep track of what happened during incidents, it also enables the continuity of information from one duty inspector to the next on shift.

Since a large part of standby duties is recording the right information to inform senior management, some teams have saved time by creating a standard template. One mode in Ontario created their template based on the most frequent questions from SITCEN and senior management. As a result, the team can consistently record the same type of information and organize it in the same way, making it easier for senior management to digest.

Practices and management

SOPs help duty inspectors in modes understand the roles and responsibilities associated with standby. However, not all groups have these SOPs and, if they do, some outline general practices instead of detailed expectations. AvSec Ontario drafted a protocol that describes a duty inspector’s day-to-day responsibilities, such as when to submit overtime claims, an obligation to attend duty inspector meetings, and being within reach of a phone/internet when on duty. This protocol includes a document called the “Criteria for Ontario Region Aviation Security On-call Duty Inspector” which every officer is required to sign before being added to the standby roster.

Standby rosters can be large or small depending on the group, number of incidents, budget, and staff availability. MSS PNR established a busy season practice where they add additional resources to manage the number of incidents. When the season slows down during the winter, the inspectors are able to handle the much lighter call volume without the added support. By establishing a busy season, the team can save money on standby when calls habitually slow down.

Finally, one best practice that many teams acknowledged during interviews is having larger rosters for standby duty rotation. Being able to take a break between shifts reduces pressure on individuals. TDG in PNR recommends six weeks as the optimal rotation period. This allows just enough time for duty inspectors to have a break but not so much that they feel rusty when returning to duty. For this group specifically, it also means relieving pressure on managers who were handling standby during the week while three RMS rotated on weekends.

Section V: Comparison of TC and other federal government department standby arrangements

We examined standby structures and practices of other federal government departments (OGD), with the aim of informing TC’s own approach to standby.

Of the six departments and agencies that we researched, CBSA, RCMP, and Public Safety’s GOC offered the best comparability to TC in terms of off-hour structures, type and frequency of incidents, and challenges they faced. NRCan, IRCC, and AAFC were less comparable, though all three departments had in place best practices worth highlighting.

Description of selected OGD standby practices

The table below provides an overview of OGD off-hours environments and standby practices in comparison to that of TC.

| Departments | Type of incidents | # Calls, average | Location of response | Positions on standby | # Staff on rotation, average | Rotation schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (Situation Centre) | Transportation accidents, safety and/or security risks | 95,000 calls a year | HQ | Non-EX | 14 | Shift work: 3 on weekdays, 2 on weekends |

| TC (Operations) | Transportation accidents, safety and/or security risks | Varied. Different groups record a few calls a year to several calls a week | HQ and Regions | EX and Non-EX | 1-4+ | Varied. No rotation to weekly rotation |

| CBSA (Border Operations Centre) | Cyber events, threats to CBSA officers, power outages, international crises, border events | 7,500 events a year | HQ | EX and Non-EX | 28 |

Working level: shifts Management: weekly |

| CBSA (Security) | Cyber events, threats to CBSA officers, power outages, border events | 1 call or incident a month | Regions | Non-EX | Up to 6-7 for a bigger region | No rotation, uses call list |

| RCMP (Criminal) | Civilian calls for help, criminal activity | Varied. Can be multiple calls a night | Local districts | Community officers and specialized units |

Working level: minimum 2 Management: 4-5 |

Varied. Hours, months, weeks. Depends on size and location. |

| RCMP (Non-Criminal) | Natural disasters, major accidents, support to other departments | Divisional Duty Officers (DDO) receive 10-40 calls a night | Regions | DDO and EX-1 equivalent | 3-5 | Shifts |

| GOC (Public Safety Canada) | Border events, national security, integrated federal response for events affecting the national interest | Multiple calls and emails from OGDs depending on emerging or ongoing events | HQ and Regions | EX and Non-EX | 3-5 | Weekly |

| NRCan | Facility security, natural disasters | 1 call every 2 months, higher during wildfires | HQ | EX and Non-EX | 1-3 | No data |

| IRCC | Facility security (i.e., alarms, evacuations) | 4-6 hours of overtime per weekFootnote 20 | HQ | Non-EX | 2-4 | Bi-weekly |

| AAFC | Facility security (i.e., alarms, evacuations) |

Farm: 1-2 calls a day Towers: 1-2 a month |

HQ | Head of Security officers | 3-5 | Bi-weekly |

CBSA

Like TC’s SITCEN, CBSA’s response hub, the Border Operations Centre (BOC), works 24/7 to triage emergencies. It follows a mix of standard operating procedures and personal judgement to know when directors need to be notified of events. Each branch at CBSA has a roster of Duty Executives whom the BOC will contact after hours if they need advice or if the event needs to be escalated to the appropriate Director General. By specifying Duty Executives to be on call, CBSA has reduced the need for all EXs to check notifications after-hours.

CBSA also has regional capacity to respond to local events. EX-levels in the regions volunteer to be on call lists and respond to the occasional (about once a month) BOC calls. These are unstructured standby positions and the volunteers do not receive standby pay. The BOC establishes weekly duty rosters for Regional Duty Executives (as with HQ executives) and will contact the lead Regional Duty Executive implicated by the event. For sustained events, regions will stand up a Regional Operations Centre (ROC) to liaise with the BOC in HQ. CBSA Security also relies on AS-levels in the regions to respond to alarms outside of the BOC structure.

RCMP

As the police of jurisdiction in eight provinces and three territories, the RCMP responds to emergency calls, public safety incidents, and other crises or events. They have organized a different after-hours response system for criminal and non-criminal incidents.

The provincial/territorial structure is divided into detachments that respond to criminal activity or civilian calls for help. Within these detachments there are two categories of standby: operational readiness and operational availability. Operational readiness is the RCMP’s equivalent of being on call where members are expected to respond immediately to an incident. Each detachment has at least two non-commissioned officers (equivalent manager-level or below) on operational readiness at any given time. Operational availability, a lighter form of standby, is reserved for specialized units, such as forensics or Police Dog ServicesFootnote 21. They are expected to respond to situations that require a particular skill in a reasonable amount of time. Finally, there are Critical Incident Commanders that rotate on a weekly basis to organize, support, or advise ongoing situations.

The RCMP also has 24/7 operational call centres in each division (province/territory) to respond to large events that threaten public safety, such as natural disasters. The call centres provide information and support to local detachments, triage requests, and determine the appropriate response. If the situation escalates beyond the centre’s scope of command and control, the call centre will notify the officer in charge of Operational Readiness and Response who will stand up the Emergency Operation Centre.

Public Safety Canada’s Government Operations Centre (GOC)

The GOC provides, round-the-clock coordination and support to key national players in the event of national emergencies and/or incidents of national interest. It shares information with all government departments, provinces, and territories depending on the type of event (e.g., security, threat, imminent disaster).

The Watch is the GOC's 24/7 centre that monitors and reports on current and/or emerging issues in Canada or internationally that could impact our national interest. Watch officers are responsible for providing analysis to senior officials, federal, provincial, and territorial entities, and non-government organizations via Notifications, Flash Alerts, and in the Daily Operations Brief.

During after-hours, the Watch is supported by an on-call Senior Operations Officer (SOO) and an on-call Executive. Depending on the criticality of the event, the Watch may call or send an immediate notification to the SOO who will then determine if additional action is required. This could include offering guidance and or direction to the Watch, briefing the on-call Executive, and in more serious occasions, initiating an integrated federal response. In a typical month, the Watch receives about 600 calls from other government departments and triages approximately 5,500 emails. A fraction of these are associated with actual, emerging, or imminent events of national interest. After-hours, the Watch informs the SOO who then notifies the on-call Executive to ensure immediate senior level situation awareness (ADM/DM). After hours, the SOO will also issue direction on certain sensitive activities by phone. Overnight, the SOO can receive up to two or three calls requiring immediate action.

The SOO will actively check emails between 16:00 and 21:00 while on duty and will keep their phones on between 21:00 and 07:00, when regular work hours take over. The SOO is also responsible for preparing briefings for Executives (DG, ADM, and Ministerial level). Like CBSA, the GOC will assign resources to extended events. In these situations, the SOO will convene other departments to manage a coordinated response. If the event lasts for an exceptionally long time, the responsibility shifts from an assigned resource to a specified event team.

NRCan, IRCC, and AAFC

NRCan, IRCC, and AAFC deal primarily with after-hours incidents at their facilities.

IRCC has one person on standby, rotating every two weeks.

AAFC has two groups on standby: one responding to building events and the other to incidents at the Experimental Farm in Ottawa.

NRCan changed their approach to handling off-hours activity following an incident at the Pickering nuclear power plant in 2020 when Canadians got an emergency alert that was sent in error. When the incident occurred, no Duty Officers were on call to triage information. Since then, NRCan has adopted the practice of having Duty Officers in place during the off-hours in case of a similar incident in the future. The arrangement now rotates two Duty Officers who field calls about incidents at their facilities as well as questions from the Government Operations Centre in the rare case of natural disasters like earthquakes, tsunamis, or nuclear meltdowns. For these events, the NRCan Duty Officer will play a coordination role between the Government Operations Centre and the appropriate NRCan sector or specialist information office, such as the Canadian Hazards Information Service.

Similarly, AAFC recently decided to change their approach by centralizing its standby structure due to the higher volume of calls in the NCR compared to the regions. The main obstacle to this standby arrangement is time zones and deciding how the Duty Officer will manage calls nation-wide when regions’ off-hours may overlap with HQ’s working hours. As AAFC organizes how to centralize their standby response in HQ, they are considering assigning two Duty Officers to be on call simultaneously, one to respond to events in western Canada and the other to events in the east. This arrangement might solve the perceived obstacle of covering Canada’s time zones.

Finding 6: Some OGD have comparable off-hour environments and standby structures to that of TC.

- Like TC, these OGD also grapple with issues of consistent standby practices and the impacts of standby duties on the well-being of individuals. Striking the right balance between national standardization and regional operational context is a key consideration, which mirrors TC’s experience.

- Almost every OGD we examined recently modified or are planning to modify some aspect of their standby practices.

Key areas of focus in this report are consistency of Safety and Security standby practices, including compensation, and the impact on the well-being of individuals performing standby duties. Below is a summary of selected OGD standby practices along those dimensions.

Consistency

As with TC, the issue of consistency is a challenge faced by the RCMP, CBSA, and to a lesser extent the GOC. These departments recognize the challenge and are exploring steps to mitigate it.

The RCMP’s standby structure is highly division oriented. Like TC’s regions and modes, each division has adopted practices that suit their geography, capacity, and style of operations. However, the RCMP has recently standardized its SOPs to bring about some degree of national consistency, while still allowing for flexibilities that accommodate each division’s specific context and needs. The RCMP has also established the National Operations Centre as their central point of control during major events. This has reduced the risk of confusion over roles and responsibilities during a crisis. For smaller events, the RCMP has relieved some pressure on on-call staff by empowering 24/7 call centre employees to dispatch operational RCMP members to respond to situations without having to notify an off-duty senior member.

CBSA’s standby structure has many similarities to TC’s: a 24/7 centre fields most calls and relays questions or complex situations to Duty Executives or Regional Duty Executives if necessary. One best practice that contributes to consistency and efficiency is daily calls between EXs to flag potential areas of concern. This information is then fed back to the BOC and priorities are marked for monitoring.

At CBSA, the issue of consistency is more of an issue for standby practices in the regions. When CBSA expanded their standby to regions, they gave them the flexibility to adapt as needed which, over time, gave rise to different practices. One result has been that the regions did not have a clear understanding of their role in relation to HQ or other departments. To address this issue, CBSA is planning to standardize regional procedures in 2022.

The GOC is located in HQ but supported by Public Safety Regional Offices when required. Until recently, there was an inconsistency regarding the application of overtime and standby claims by regional staff which created a perception of unfairness and unequal compensation, however this has since been addressed.

As an additional best practice, the GOC provides their management with a schedule of who is on duty. With the understanding that the SOOs are responding to emergent and ongoing events, senior GOC leadership will prioritize their incoming calls and emails. This direct line from the SOO to GOC management has helped the GOC’s efficiency. The SOO meets with their colleagues on a weekly basis to review procedures and discuss recent incidents.

There were no discernable consistency issues in the other departments and agencies examined. However, AAFC only recently centralized its standby structure to the NCR. This is intended to result in a more consistent approach. To ensure that regions’ perspectives are taken into account, duty officers will be sent to the regions to become familiar with their facilities.

Lastly, NRCan and IRCC in particular, but also AAFC, mentioned the need to have senior, experienced staff (e.g., manager-level) as Duty Officers. As with TC, the role requires an understanding of departmental structures and hierarchy, and a certain level of experience.

Well-being of individuals performing standby duties

The analytical challenge for this aspect of the comparison exercise has been to tease out the level of workload and stress generated by overall emergency management requirements (which includes regular work hours) as opposed to challenges specific to off-hours work. That said, we were able to glean useful observations.