Internal audit report outlining results of the assessment of the Review of the National Aircraft Certification Program at Transport Canada.

On this page

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Findings and recommendations

- 3. Conclusions

- 4. Management response and action plan

- Annex A – List of certification project categories

- Annex B – List of acronyms

Executive summary

Introduction

Transport Canada’s Civil Aviation (TCCA) National Aircraft Certification (NAC) Program regulates and oversees standards for aeronautical productsFootnote 1 designed and operated in Canada, and guides the aerospace industry with respect to certification in highly technical fields.

Objective and scope

The objective of this review was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of the NAC Program’s approach to certifying aeronautical products, including design, implementation and oversight of its delegation program. Our review focused on the Headquarters NAC processes.

Background: NAC program processes

The NAC Program is responsible for processes relating to the:

- delegation of technical experts allowing them to perform certification activities on behalf of the Minister of Transport

- oversight of the delegates during and outside of the certification activities

- certification of domestic aeronautical products and validation of internationally manufactured aeronautical products and

- continuing airworthiness of registered aeronautical products

Overall conclusion

Overall, our review found that the program’s processes are sound and carried out professionally to effectively mitigate the risks to meeting NAC’s objectives and fulfilling its mandate. Our review also identified opportunities to strengthen the program.

Opportunities to strengthen the program

Prior to our review, the NAC Program had already begun several improvement initiatives, all at varying stages of implementation. During the review, we verified the progress of these initiatives and also identified further opportunities to strengthen the program.

Given the significant impacts on the global aviation industry from increasing complexity, continued growth and renewed focus on aeronautical product certification, it would be beneficial to evaluate the current and expected demand for aircraft certification to assist with future resource planning. A human resources (HR) strategy should be developed to meet NAC objectives. Also, documenting the technical competencies for the NAC specialty groups would provide a foundation for the development of a formalized learning curriculum to address the specific technical development needs.

Although there is detailed NAC Program guidance available for carrying out the processes, it needs to be kept up to date and provide clear guidance for documenting key decisions. The program should complete its initiatives underway to ensure guidance is kept current to help maintain consistent NAC practices and procedures. The program should also implement improvements to supporting information technology (IT) systems that are used by NAC as repositories for the required supporting documents for certification and continuing airworthiness projects.

While there is an overarching TCCA Quality Assurance program for the whole Civil Aviation Program, NAC has recognized the importance and benefit of formalizing quality assurance and control processes into a dedicated Quality Management System (QMS) UnitFootnote 2 within NAC. Despite not having its own QMS Unit, the existing management practices as well as the knowledge and expertise of staff help to ensure a well-managed program. There is no indication from our review that the quality of the work or the safety of aeronautical products are negatively impacted, or that the program is not fulfilling its mandate.

As certification and continuing airworthiness projects are often complex and involve several members from different specialties, NAC would benefit from using project management information technology systems to assist with planning, scheduling, and tracking projects on a real-time basis and with managing workloads and performing trend analysis. As such, the NAC Program should implement its planned initiative to improve certification project management and also develop and implement a plan for continuing airworthiness project management. The NAC Program would also benefit from establishing specific outcomes and indicators to measure its performance.

Delegation is the process of authorizing technical experts, external to Transport Canada, to perform certification activities on behalf of the Minister of Transport. Delegates are authorized to determine compliance with applicable design standards, with varying degrees of oversight from NAC.Footnote 3 The level of due diligence that NAC performs varies from delegate to delegate, based on the level of familiarity it has with the delegate, the delegate’s level of experience, and history. In most cases, the enterprise requiring certification of its aeronautical product is the employer of the delegate performing the certification activities, which presents an inherent conflict of interest (COI). Like other global equivalent certification authorities, the NAC delegation process is based on a review of the delegates’ experience and the trust that the certifying authority has of the delegate. The NAC Program provides direct oversight of the delegates’ work during the certification process. Additional safeguards are employed to mitigate the risks of business pressures, such as timelines and budgets, coming in conflict with regulatory interests.

Continued monitoring and strengthening of the safety cultures of enterprises, their delegates as well as the NAC organization would help to maintain the effectiveness of existing safeguards. This could include fully implementing the new voluntary Safety Management System (SMS) program and developing an approach to monitor attitudes and perceptions of NAC staff and delegates regarding the effectiveness of the safeguards in place to maintain delegate objectivity. Consideration could also be given to dedicating more effort to the delegate surveillance inspections as delegates may be more willing to raise issues in interviews that are held outside of the regular certification process.

Following direction from the Standing Joint Committee on the Scrutiny of Regulations and the Department of Justice, surveillance findings of non-compliance can now be made only against the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs). This change impacts NAC’s delegate surveillance process as it does not have an associated CAR or mandatory SMS obligations; findings are instead made against compliance with delegates’ Procedures Manuals. This issue must be resolved to ensure the continued effectiveness of NAC’s oversight of delegates.

We have made recommendations to address these findings and management has developed an action plan to implement them.

Statement of conformance

This Review conforms with the Government of Canada’s Policy on Internal Audit and the Institute of Internal Auditors’ International Standards for the Professional Practice of Internal Auditing, as supported by the results of an external assessment of Internal Audit's Quality Assurance and Improvement Program.

Chantal Roy, Chief Audit and Evaluation Executive

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose

The Review assessed the adequacy and effectiveness of the National Aircraft Certification’s (NAC) approach to certifying aeronautical productsFootnote 4, including design, implementation and oversight of its delegation program. Our review focused on the Headquarters (HQ) NAC Program.

1.2 Background

Transport Canada’s Civil Aviation (TCCA) NAC Program regulates and oversees standards for aeronautical products designed and operated in Canada, and guides the aerospace industry with respect to certification in highly technical fields.

As a result of the COVID-19 (Corona Virus 2019) pandemic and the corresponding fears of contagion during travel, the global airline industry has suffered significantly. The impacts on the aviation sector create uncertainty and implications for the regulatory, oversight, and service processes provided by the TCCA branch to the aviation industry. Despite these uncertainties, the certification of aeronautical products will continue to play a critical role to help ensure their safety.

Within TCCA, the NAC Program is responsible for certifying aeronautical products. The NAC Director reports to the Director General, Civil Aviation, who reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) of Safety & Security (S&S), who in turn reports to the Deputy Minister.

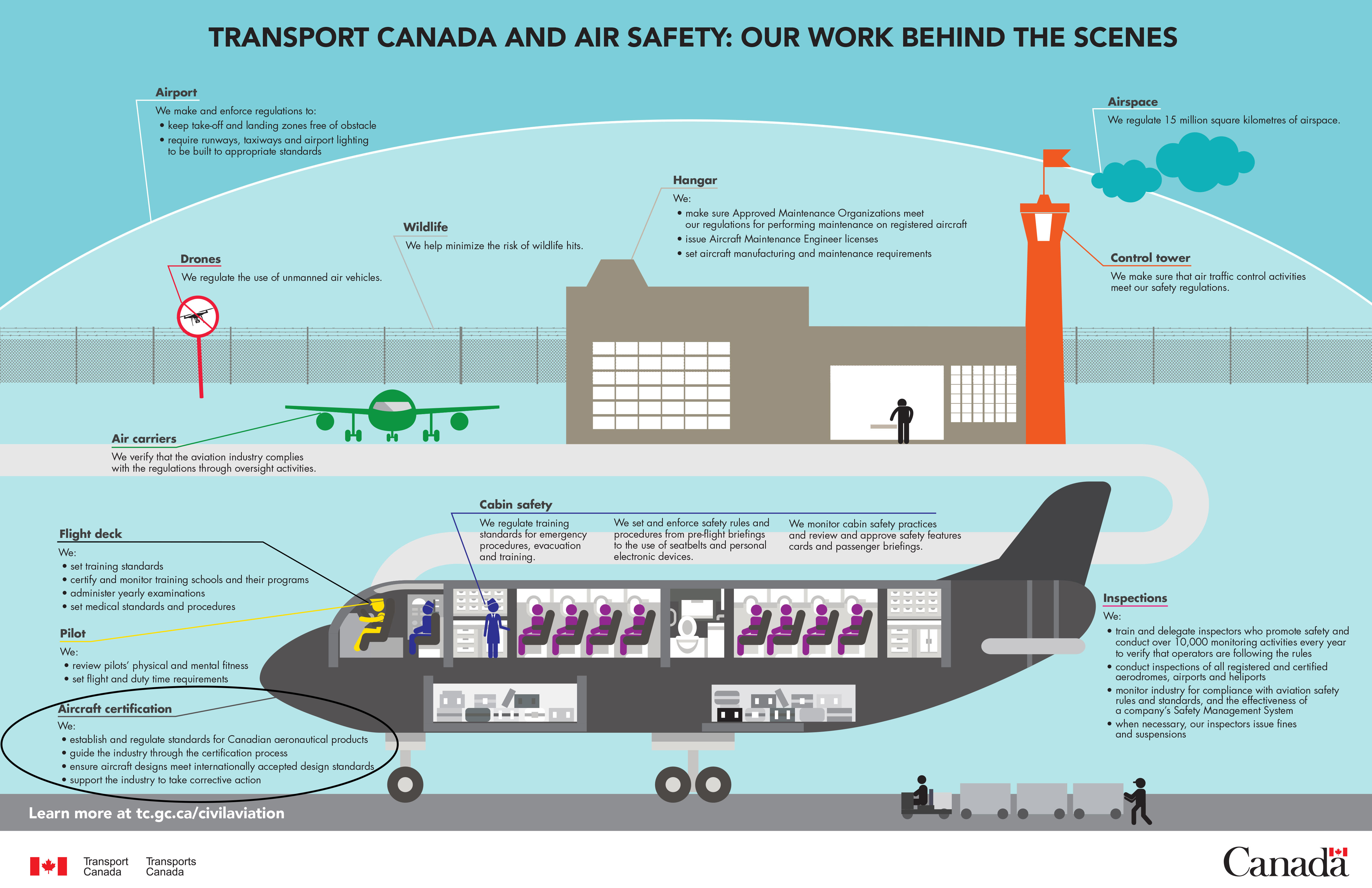

Figure 1

Figure 1 illustrates TCCA processes, and highlights (circled below) the focus of this review.

Figure 1: Transport Canada and Air Safety: Our work behind the scenes

This illustration depicts TCCA processes. Aircraft Certification is circled as it is the focus of this review.

Airport: We make and enforce regulations to:

- keep take-off and landing zones free of obstacle

- require runways, taxiways and airport lighting to be built to appropriate standards

Drones: We regulate the use of unmanned vehicles.

Wildlife: We help minimize the risks of wildlife hits.

Hangar: We:

- make sure Approved Maintenance Organizations meet our regulations for performing maintenance on registered aircraft

- issue Aircraft Maintenance Engineer licenses

- set aircraft manufacturing and maintenance requirements

Airspace: We regulate 15 million square kilometers of airspace.

Control tower: We make sure that air traffic control activities meet our safety regulations.

Air carriers: We verify that the aviation industry complies with the regulations through oversight activities.

Flight deck: We:

- set training standards

- certify and monitor training schools and their programs

- administer yearly examinations

- set medical standards and procedures

Pilot: We:

- review pilots’ physical and mental fitness

- set flight and duty time requirements

Aircraft certification: We:

- establish and regulate standards for Canadian aeronautical products

- guide the industry through the certification process

- ensure aircraft designs meet internationally accepted design standards

- support the industry to take corrective action

Cabin safety:

- We regulate training standards for emergency procedures, evacuation and training.

- We set and enforce safety rules and procedures from pre-flight briefings to the use of seatbelts and personal electronic devices.

- We monitor cabin safety practices and review and approve safety features cards and passenger briefings.

Inspections: We:

- train and delegate inspectors who promote safety and conduct over 10,000 oversight and certifications activities per month to verify that operators are following the rules

- conduct inspections of all registered and certified aerodromes, airports and heliports

- monitor industry for compliance with aviation safety rules and standards, and the effectiveness of a company’s Safety Management System

- when necessary, our inspectors issue fines and suspensions

The following paragraphs summarize the NAC Program’s key processes.

Delegation

Delegation is a well-established, internationally recognized practice followed by global regulators. Through the Aeronautics Act, TCCA authorizes delegates to perform engineering services to secure certification of aeronautical products on behalf of the Minister of Transport.Footnote 5 Delegation is also used in other TCCA aviation functions, such as pilot check rides. Delegation provides access to a larger pool of technical resources and expertise in the aeronautical industry, leading to improved efficiency and response times. Delegates are authorized to determine compliance with applicable design standards, with varying degrees of oversight from NAC.Footnote 6 The level of due diligence that NAC performs varies from delegate to delegate, based on the level of familiarity it has with the delegate, the delegate’s level of experience, and previous performance.

The NAC delegation process is based on the requirements of the Canadian Aviation Regulation (CAR) Airworthiness Manual (AWM). At Headquarters (HQ), the NAC Delegations and Surveillance team is responsible for evaluating applicants to determine if they meet the CARs. The team is also responsible for the ongoing oversight of the authorized delegates outside of the regular certification activities to help ensure compliance with regulatory requirements.

Certification/Validation

Certification of aeronautical products requires the examination and approval of proposed type designs and changes to type designs to verify and ensure the products comply with the CARs and incorporated-by-reference standards applicable to that product. There are six key categories of certification projects (see Annex A).

At HQ, NAC primarily conducts initial type design and changes to type design certification for the larger manufacturers in Canada (e.g., Bombardier, Pratt & Whitney).Footnote 7 The Engineering team carries out the certification activities, which include the oversight of the delegates during this process. The Flight Test team tests aircraft performance, stability and control as part of the demonstration of the product’s compliance with the CARs.

TCCA regulates and oversees standards for aeronautical products designed and operated in Canada, and guides the aerospace industry with respect to certification in highly technical fields such as aircraft design, structures, avionics, and power plants.Footnote 8 TCCA is a “certificating authority” when it fulfills the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) responsibilities of a “state of design” to regulate the design, production, and airworthiness approval and environmental certification of civil aeronautical products originated in Canada. Each year, TCCA approves more than 1,500 new and modified aeronautical products built or operated in Canada.Footnote 9

TCCA is also responsible for validating that internationally manufactured aeronautical products comply with the CARs and are safe for use in Canada. As such, TCCA is a “validating authority” when it fulfills the ICAO responsibilities of a “state of registry” to regulate the design, production, and airworthiness approval and environmental certification of civil aeronautical products imported from another state (e.g. U.S.). ICAO has set out a recommended practice whereby global state authorities may accept the original state of design’s completed certification or use it as the basis for validating the certification compliance, rather than re-performing the same in-depth examination of compliance. This process allows the validating authority independence and flexibility in scaling its level of involvement according to risk.

TCCA has separate bilateral aviation safety agreements (BASA) with the U.S. Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) and the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA).Footnote 10 TCCA is currently working on a BASA with the Brazil National Civil Aviation Agency (ANAC). Decisions to enter into bilateral agreements involve evaluations of the country’s systems and processes to ensure sufficient equivalency, as well as assurance of sufficient experience and credibility.Footnote 11

There are several benefits to relying on equivalent certification authorities for certification decisions. As it may take several years to conduct the full certification process, validating a certification instead of carrying out the entire process allows for a greater number of aircraft to be certified while ensuring compliance to standards. As certification is expensive for manufacturers, it also allows fair treatment since manufacturers are not required to pay for the duplication of work that would result in the same decisions.

Continuing airworthiness

As per ICAO requirements, Canada is responsible for maintaining the airworthiness of certified aeronautical products. NAC’s continuing airworthiness (CAW) process ensures compliance with the CARs by overseeing the safety performance of all registered aeronautical products for which Canada is the state of design. For example, it reviews safety data, conducts investigations, issues advisories and warnings, and determines corrective actions when required.

Involvement at the international level

TCCA is actively involved in ICAO to set the international standards for aviation safety. TCCA also participates in several ICAO panels, working groups and committees such as the Cooperative Development of Operational Safety and Continuing Airworthiness Program. This helps ensure Canada’s interests and positions are represented internationally.

TCCA is also part of the Certification Management Team (CMT) along with the FAA, EASA, and ANAC. The CMT works to harmonize solutions to common authority and industry issues. TCCA participated in the Joint Authorities Technical Review (JATR) of the Boeing 737 MAX Flight Control System. The report was released on October 11, 2019, and included 12 recommendations to the FAA.

1.3 Review objective, scope, criteria and approach

Objective and scope

The objective of this review was to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of NAC’s approach to certifying aeronautical products, including design, implementation and oversight of its delegation process. Our review focused on the Headquarters NAC processes.

Criteria

We expected there would be in place:

- an organizational structure defined by clear roles and responsibilities and effective lines of communication and reporting

- sufficient resources including staff with the required knowledge, skills and capacity to implement and manage the certification process, including oversight activities such as monitoring delegates and continuing airworthiness of approved products

- operational policies, standard operating procedures (SOPs), guidance material, and tools required to effectively implement and manage the delegation, certification and related oversight activities, as well as the continuing airworthiness oversight activities

- quality control and quality assurance processes to assess whether the program activities are being implemented, are effective and continuously improved

- performance indicators that measure the effectiveness and efficiency of the program

- an over-arching project management system in place for prioritizing and assigning work to staff

Approach

Initially, we planned on completing this review in two phases. Phase I was to examine how TCCA fulfills its role and responsibilities as a “Certificating Authority” while Phase II was to examine how TCCA fulfills its role and responsibilities as a “Validating Authority”. However, as the NAC Review progressed, it was determined that both phases would be completed concurrently since TCCA’s roles and responsibilities as a validating authority are closely related to the domestic certification process.

Our approach included interviewsFootnote 12, document reviews, file reviewsFootnote 13, and walk-throughs of NAC systems to assess the NAC Program against the criteria.

We leveraged internal related work that has recently been conducted such as TCCA’s review of its organizational structure and governance, as well as a 2018 assessment of the Certification of Aeronautical Products performed by TCCA’s Quality Assurance (QA) function.

We also reviewed and leveraged external reports such as the Joint Authorities Technical Review (JATR) and U.S. Blue Ribbon Panel - Official Report of the Special Committee to review the Federal Aviation Administration’s Aircraft Certification Process.

1.4 Report structure

The report summarizes the Review’s findings under three sections: Governance and Program Management; Risk Management; and NAC Continuing Airworthiness Processes. Each section is organized into the following: what we expected, details of our assessment, and, where appropriate, recommendations.

2. Findings and recommendations

Prior to our review, the NAC Program had already begun several improvement initiatives, all at varying stages of implementation. For example, an organizational structure change was implemented that is expected to improve certification process consistencies. A certification management improvement project was initiated to improve guidance material as well as project management. A continuing airworthiness (CAW) review had begun to update and improve guidance materials. Plans were also underway to create a Quality Management System (QMS) unit within NAC. Additionally, a risk-based approach for planning targeted surveillance inspections was recently implemented to replace the previous cyclical monitoring approach. Thus, during the review, we verified the progress of these initiatives and also identified further opportunities to strengthen the program.

2.1 Governance and program management

2.1.1. NAC governance structure

Internal Audit expected

We expected that the organizational structure is defined by clear roles and responsibilities and effective lines of communication and reporting.

Internal Audit’s assessment

Through interviews with NAC staff, we found there is a good understanding of roles and responsibilities as well as good communication within HQ NAC and the regions. Also, the Aircraft Certification Consultation Team (ACCT) committee meetings provide a national forum to discuss challenges and share best practices.

Recent changes have been made to the organizational structure, with the transfer of the regional aircraft certification teams to HQ NAC. This change is expected to help address certification process inconsistencies identified in previous reviews and improve a working model where resources are shared and multi-disciplinary certification teams are created. A team led by the NAC Director is currently developing a Transition Plan with an approach to address the cultural, strategic and structural changes required to implement the new governance model.

2.1.2. NAC Human Resources

Internal Audit expected

We expected that there are sufficient resources with the required competencies and knowledge to carry out the NAC Program.

Internal Audit’s assessment

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a major issue for TCCA, including the NAC Program, was the ongoing difficulty in recruiting and retaining qualified and specialized staff. Staff are typically recruited from the aviation industry. However, with the recent significant impacts of the pandemic on the global aviation industry, demand for certification work may change and the NAC Program will need to reassess its resource requirements over the short, medium and longer term.

No workload analysis to determine staffing requirements

Although staff shortages have been an ongoing concern, workload analysis has not been conducted to support the requirement for additional staff. Currently there is a lack of data to measure the workload or determine staffing requirements since there are issues with the TCCA systems used to capture and track workload activities for resource planning and cost recovery of services provided to enterprises.Footnote 14 However, a new Cost Recovery Service Management (CRSM) system is planned for implementation which will include a functionality for tracking hours worked, cost recovery and service standards.

Planning NAC resources is a challenge and could be better supported by an HR plan or strategy

Planning resources for the workload is difficult in the NAC environment as it is a demand driven industry and the level of demand fluctuates. Plans are mostly based on historical data and estimates of upcoming work based on current aerospace market conditions and discussions with enterprises. There is no overarching HR strategy to assist in planning NAC resources.

Lack of a specific technical training and development curriculum

There is no documented engineering development program to help attract potential candidates. Budget constraints over the past few years have impacted training funds and most engineers learn on the job and from their interactions with industry.

There is no formal documented learning curriculum for developing technical competencies to support staff in the evolving aerospace industry. Recently, technical competencies were drafted for the various specialty groups in TCCA, including NAC, but this work is on hold.

Recommendation #1

The NAC Program should conduct analysis to determine the short, medium and long-term demand for aircraft certification and create an HR strategy to meet NAC objectives. This should include finalizing the technical competencies for the specialty groups and developing a formal learning curriculum to address NAC’s specific technical development needs.

2.1.3. NAC program guidance and tools

Internal Audit expected

We expected that the NAC Program processes would be supported by current, clear and comprehensive guidance and tools for both staff and industry.

Internal Audit’s assessment

The CARs specify the legislative requirements for the NAC processes. These legislative requirements are described in various chapters of the Airworthiness Manual (AWM).Footnote 15

TCCA guidance

Staff Instructions (SIs), based on the CARs requirements, are the main source of guidance for the NAC Program. We identified the following issues with the guidance for staff.

Guidance is outdated

The full suite of SIs is outdated. The Aircraft Certification Standards division of the TCCA Standards Branch is responsible for developing new and revised guidance material with input from engineer specialists, but the division has a work backlog preventing updates to guidance. It is also difficult for the NAC engineer specialists to dedicate time to keep guidance current due to existing workloads. Instead, staff rely on their knowledge and experience. Such knowledge and experience is often not easily transferred to new hires and presents a challenge when staff retire or leave the organization. While the existing management practices as well as the knowledge and expertise of staff help to ensure a well-managed program, outdated guidance makes it more challenging to standardize practices and in turn impacts the ability to develop and implement a formal quality assurance process. (Our findings and recommendation regarding quality assurance are presented in Section 2.1.4.)

Recently, NAC began two initiatives - the certification management improvement project, and the continuing airworthiness (CAW) review - to update and improve guidance materials but work has progressed slowly due to operational priorities.Footnote 16

There is also a unique situation, where the NAC guidance includes outdated information which NAC is not solely responsible to update. The NAC Program must apply the Changed Product Rule (CPR)Footnote 17 when it assesses changed type designs as part of the certification process. Since the CPR is a harmonized rule that was created by TCCA, FAA, EASA and ANAC, it must be updated in collaboration. A CPR International Working Group was recently formed to update the guidance and plans for its implementation in three years. In the meantime, NAC Program management considers the existing CPR guidance as still useful and is satisfied with how it is being applied.

Guidance does not include working level procedures

The SIs do not include working level descriptions of specific procedures including the requirements for documenting key decisions. For example, for both the delegation and certification processes, there is a pre-application phase where extensive communication and interaction with the applicant takes place and key decisions are made. However, the SIs do not provide guidance or describe requirements for formally documenting these decisions.

With respect to the surveillance of delegates during the certification process (see section 2.2.2.), the related SIFootnote 18 does not provide guidance to help the NAC engineer specialists in risk analysis and decision making. Also, there is no guidance or requirements to document their activities and decisions.

TCCA tools

The Delegation and Surveillance unit, within NAC, uses the Record, Document and Information Management System (RDIMS) as a repository for the required supporting documents for delegate files and delegate surveillance inspections. It also uses a centralized national database, the Delegate Information System (DIS), to retain data for each delegate and to generate reports. We found data reliability issues with DIS when determining the sample of delegate files for our file review, and informed NAC; they are addressing the identified issues.Footnote 19

The NAC Project Management group uses the National Aeronautical Product Approval (NAPA) database as a repository for the required supporting documents for certification projects, but there are several issues with it. For example, information searches cannot be performed since documents are scanned and attached, and only basic query reports can be generated.

The CAW group uses the web based Continuing Airworthiness Web Information System (CAWIS) as a repository for all CAW-related data from various sources (e.g., Annual Airworthiness Reports (AAIRs)) as well as a project tracking system for Service Difficulty Reports (SDRs) and Airworthiness Directives. Although CAWIS is a critical system for safety data, it is often unreliable and requires a dedicated IT employee to keep it operating. There are also reporting challenges as CAWIS does not have a reporting functionality.

Industry guidance and training

Industry must follow the delegation, certification and continuing airworthiness requirements within the CARs. TCCA provides guidance material to industry, based on the CARs, in the form of Advisory Circulars (ACs). Since the ACs follow the same format and include much of the same content as the SIs, they share the same issues described above.

TCCA managers who are responsible for delegates set extensive training requirements and work with industry to develop training plans for each candidate delegate. In addition, TCCA strongly recommends the completion of the TCCA Aircraft Certification Specialty Course during a candidate delegate’s developmental training period. However, TCCA allows enterprises to design and deliver their own version of this course. TCCA has developed guidance to support consistent learning objectives and content, and recommends a TCCA representative attend/participate when a training course is delivered, but this is not always followed in practice.Footnote 20 Despite this situation, there is no indication that delegates are not receiving quality training.

Recommendation #2

The NAC Program should complete its improvement initiatives underway to ensure guidance is kept current to help maintain consistent NAC practices and procedures. This includes:

- Updating and finalizing guidance documents for:

- delegation

- certification (including level of involvement (LOI) surveillance and the Change Product Rule)

- continuing airworthiness (including the Service Difficulty Report (SDR) risk assessment tool)

- documenting key decisions

- Implementing NAPA and CAWIS system improvements.

2.1.4. NAC Quality Assurance and performance measurement

Internal Audit expected

We expected that there is a Quality Assurance (QA) process in place to assist in the consistent application of the NAC Program processes.

We also expected that specific measurable program performance outcomes are defined and monitored.

Internal Audit’s assessment

Quality Assurance (QA)

While there is an overarching TCCA Quality Assurance (QA) program for the whole Civil Aviation Program, which includes the NAC Program, there is no formal quality assurance unit in place specifically for NAC. There are plans underway to create a Quality Management System (QMS) unit within NAC. Despite not having its own QMS Unit, the existing management practices as well as the knowledge and expertise of staff help to ensure a well-managed program. It is important to note, there is no indication from our review that the quality of the work or the safety of aeronautical products are negatively impacted, or that the program is not fulfilling its mandate.

Internal Audit’s examination of NAC files

The internal audit team examined random samples of project files, for NAC HQ delegates, delegate surveillance, and certification projects, to determine if the supporting documentation retention practices are conducted in a consistent and timely manner according to existing guidance.

The testing of the delegate files retained in RDIMS found that less than half included the required supporting documents, such as the application for delegation. While the documents should be in RDIMS and easily accessible, some of the documents not found for our testing may be in NAC file cabinets.Footnote 21 Also, although not a required practice, some NAC engineers complete a checklist template when evaluating each type of delegate applicant. Making it a requirement to complete and include this checklist in the delegate file would be helpful for QA purposes.

The examination of delegate surveillance files retained in RDIMS found the required supporting documents included on file, with a few exceptions.

The testing of initial and changed type design certification project files in NAPA, including foreign validation project files, found that most of the files examined included the required supporting documents.Footnote 22

Performance measurement

Although there are performance indicators for TCCAFootnote 23 there are no specific performance outcomes and indicators defined for the NAC Program. There is no specific logic model for the program which would help to identify the key inputs, outputs and outcomes, and to assign relevant performance measures.

Although there are several initiatives underway within the Department working to improve performance measurementFootnote 24, there are no plans to assist the NAC Program to define its outcomes and indicators.

Recommendation #3

The NAC Program should complete the implementation of a Quality Management System (QMS) unit. It should also leverage current departmental performance measurement work to assist in developing an approach to define specific NAC Program outcomes and indicators to measure performance.

2.1.5. NAC Project Management

Internal Audit expected

We expected that there is an overarching project management system in place for prioritizing projects, tasks, assigning work to staff, and monitoring progress.

Internal Audit’s assessment

Certification Project Management

As described in section 2.1.3., the NAC Project Management group is responsible for managing initial, and changes to, type design certification projects. They coordinate the appropriate NAC engineering specialists to conduct certification work and act as the primary communication hub for the applicant and the NAC engineers throughout the certification process.

There is no overarching project management information technology system in place to plan, schedule and track certification projects on a real-time basis. Therefore managing workloads or performing trend analysis (e.g., duration of project) is not possible. A spreadsheet is used to track the status of some of the action items for certification projects, but this method is not ideal since most certification projects are complex and may involve several engineers with different specialties, each being responsible for a portion of the project.

As part of the Project Management group’s certification management improvement project (described in section 2.1.3.), an Operational Governance FrameworkFootnote 25 was developed to assist with project management, but work has not progressed due to operational priorities. It should be noted that in January 2021, a Project Manager has been assigned to lead the implementation of this initiative.

In addition, there had been plans to include project management functionality in the CRSM system (described in section 2.1.2) but it will not be included in the initial version. Future functionality enhancements are planned.

Continuing airworthiness project management

The continuing airworthiness (CAW) group does not have a project management information technology system to plan resources, assign and manage work, and track timelines. An engineer responsible for a given manufacturer who needs to make changes that involve several specialties has to deal with many colleagues, making coordination complex.

Recommendation #4

The NAC Program should implement its planned initiative to improve certification project management and develop and implement a plan for continuing airworthiness project management.

2.2 Risk management

2.2.1. NAC delegation: Managing Conflict of Interest

Internal Audit expected

We expected that there are safeguards in place to mitigate conflict of interest and maintain transparency and independence of delegates.

Internal Audit’s assessment

In most cases, the enterprise requiring certification of its aeronautical product is the employer of the delegate performing the certification activities, which presents an inherent conflict of interest. Like other global equivalent certification authorities, the NAC delegation process is based on trust and experience, and NAC directly oversees delegates’ work during the certification process. Additional safeguards are employed to mitigate the risks of business pressures, such as timelines and budgets, coming in conflict with regulatory interests.

Most delegates are professional engineers and are expected to adhere to their profession’s code of ethicsFootnote 26. As well, although not public servants, all delegates are expected to respect the spirit of the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector. Most importantly, TCCA has a hands-on approach during the certification process. Throughout the certification process NAC Engineers strive to establish a close professional relationship with frequent interaction to foster trust with the delegates. NAC’s goal is for delegates to bring forward issues, share information openly with the NAC Engineers and ask for help when needed.

TCCA also conducts ongoing surveillance of delegates that includes interviews with them outside of the regular certification process (see section 2.2.2). According to NAC representatives, while this surveillance is important, it only accounts for a small percentage of the total oversight activities and therefore its contribution to promoting compliance is considered quite small. Through our file review, however, we noted the value of these surveillance inspections and suggest consideration be given to increasing these inspections as delegates may be more open to raising issues in this setting.

Based on our research, other certification authorities have some additional safeguards that TCCA may wish to consider to help maintain delegate independence. For example, the FAA has an anonymous online reporting system, and the EASA uses COI declarations for delegates and issues penalties for non-compliance.

To further improve safety, many regulatory organizations are taking steps to strengthen not only their own safety culture but also the safety culture of the entities they oversee. Several recent studies and reports highlight the importance of safety culture, which contributes to achieving a total organizational commitment to safety.Footnote 27 A focus on strengthening safety culture recognizes that safety improvements not only involve standards, oversight and compliance, but also require the capacity to anticipate potential safety risks and for continuous organizational learning. As regulators monitor and assess the safety culture of the operators and delegates, they also need to strengthen their own organizational safety culture.

TCCA is in the process of implementing a voluntary Safety Management System (SMS) program for Design Approval Organizations approved Manufacturers. This system is being implemented in the absence of applicable regulations to help align Canadian compliance with ICAO Annex 19 obligations, as well as to respond to industry demand for recognition of their SMS in order to be able to sell their products and services around the world. A key aspect of any SMS is the concept of a positive safety culture, which TCCA should be considering as part of the safety management systems implemented by enterprises.

TC has been taking steps to develop a multimodal approach to promote and oversee safety culture. The Safety and Security Strategic Planning & Policy Coordination team is formulating an approach to safety culture to enhance Safety and Security’s Oversight regime as the department modernizes its approach to risk management, regulations and oversight.

Recommendation #5

The NAC Program should continue to promote and monitor the safety culture of the enterprises and the delegates they oversee, as well as its own staff. This should include fully implementing the new voluntary SMS program and developing an approach to monitor attitudes and perceptions of NAC staff and delegates regarding the effectiveness of the safeguards in place to maintain delegate objectivity. Consideration should also be given to dedicating more effort to the delegate surveillance inspections as delegates may be more open to raising issues outside of the regular certification process.

2.2.2. NAC risk assessment tools

Internal Audit expected

We expected that risk assessment tools and techniques are used to plan and carry out:

- Level of involvement (LOI) surveillance of delegates during the course of the certification process;

- Ongoing surveillance inspections of delegates outside of certification activities; and

- Assessments of continuing airworthiness Service Difficulty Reports (SDRs).

Internal Audit’s assessment

NAC uses several tools to assess risk and plan activities:

Risk assessment tool for LOI surveillance of delegates

During the certification process, when an enterprise’s delegates demonstrate the aeronautical product’s compliance with applicable CAR requirements, NAC engineer specialists perform surveillance of the delegate’s work according to a level of involvement (LOI) assessment.

The engineer specialists take the delegate’s level of authorityFootnote 28 into account and determine the type and extent of the LOI surveillance activities by applying the LOI risk criteria that are based on factors such as type design complexity and the delegate’s past performance. Based on this risk analysis, LOI activities are determined, such as the review of compliance reports or participation in flight tests. For example, LOI will be greater when the risk of non-compliance of the type design of a product would result in a more serious consequence. The tool helps to assess risk and to determine the LOI required to oversee delegate certification work.

Risk assessment planning tool for delegate surveillance

The NAC Program is responsible for the ongoing oversight of the delegates, in addition to the regular certification activities, to determine if delegates remain in compliance with regulatory requirements.

NAC has recently developed a risk-based approach for planning targeted surveillance inspections to replace the previous cyclical monitoring approach. A planning tool assesses the delegated entities (DARs, DAOs / AEOs and APs)Footnote 29 based on a number of quantitative and qualitative risk factors, such as complexity of the business, number of previous findings and their severity. Although this is an improved approach, it is too early to determine its effectiveness as it was first used in 2020/21 and is not yet fully implemented.

Following recent direction from the Standing Joint Committee on the Scrutiny of Regulations and the Department of Justice, TCCA is now required to make surveillance findings of non-compliance against the CARS. It will no longer make any findings of non-compliance for failure to comply with certificate holder developed manuals, programs, systems or procedures, whether or not they are still required to be complied with by regulation. This change impacts NAC’s delegate surveillance process as there is no associated CAR. Following this change in direction, an “observation form”Footnote 30 was introduced to communicate identified non-compliance with approved manuals to certificate holders and delegates. The Standards Branch and NAC are currently working on the integration of this new tool in the day-to-day surveillance practices.

Risk assessment planning tool for assessing SDRs

Certificate holders (operators/manufacturers) are required to submit Service Difficulty Reports (SDRs) to the NAC continuing airworthiness (CAW) group to inform of incidents of malfunctioning or defective aeronautical products. CAW assesses the SDRs and if a potentially unsafe condition exists, it conducts an assessment to determine the level of risk using a matrix based on hazard severity and hazard probability. If required, the operator/manufacturer is required to develop a risk mitigation or corrective action plan.Footnote 31 The risk assessment process helps to determine the related risk and corrective actions.

As required by ICAO, CAW has also started to carry out trend analyses of the SDRs, including those received from the other certifying authorities.Footnote 32 Quarterly reports are produced for the more at-risk aircraft, with less frequent reports for other aircraft.Footnote 33 As SDR trend analyses is relatively recent, guidance is being developed which will link to the SDR guidance and help define which models to look at based on risk.

Recommendation #6

TCCA must resolve the issue created by a recent change that requires surveillance findings of non-compliance be made against CARs, and not manuals, to ensure the continued effectiveness of NAC’s oversight of delegates.

2.2 Continuing Airworthiness (CAW) Processes

In addition to the SDR process, we reviewed the other CAW activities and found no issues with the processes used to monitor the safety of certified aeronautical products. For example, we found that CAW:

- develops and issues Airworthiness Directives (ADs) to the relevant certificate holders and the global civil aviation authorities for corrective action required to resolve an unsafe condition.Footnote 34 CAW monitors the progress and effectiveness of the corrective actions through a follow-up process with the certificate holders and determines if additional actions are required.Footnote 35

- collects and updates airworthiness data required by TCCA, Statistics Canada and the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) through Annual Airworthiness Information Reports (AAIRs).Footnote 36

We also compared ICAO requirements against TCCA regulations and procedures and found that TCCA is in compliance with the key requirements for continuing airworthiness.

3. Conclusions

Overall, our review found that the program’s processes are sound and carried out professionally to effectively mitigate the risks to meeting NAC’s objectives and fulfilling its mandate. Prior to our review, the NAC Program had already begun several improvement initiatives, all at varying stages of implementation. During the review, we verified the progress of these initiatives and also identified further opportunities to strengthen the program.

Given the significant impacts on the global aviation industry from increasing complexity, continued growth and renewed focus on aeronautical product certification, it would be beneficial to evaluate the current and expected demand for aircraft certification to assist with future resource planning. A human resources strategy should be developed to meet NAC objectives. Also, documenting the technical competencies for the NAC specialty groups would provide a foundation for the development of a formalized learning curriculum to address the specific technical development needs.

Although there is detailed NAC Program guidance available for carrying out the processes, it needs to be kept up to date and provide clear guidance for documenting key decisions. The program should complete its initiatives underway to ensure guidance is kept current to help maintain consistent NAC practices and procedures. The program should also implement improvements to supporting information technology systems that are used by NAC as repositories for the required supporting documents for certification and continuing airworthiness projects.

While there is an overarching TCCA Quality Assurance program for the whole Civil Aviation Program, NAC has recognized the importance and benefit of formalizing quality assurance and control processes into a dedicated Quality Management System (QMS) UnitFootnote 37 within NAC. Despite not having its own QMS Unit, the existing management practices as well as the knowledge and expertise of staff help to ensure a well-managed program. There is no indication from our review that the quality of the work or the safety of aeronautical products are negatively impacted, or that the program is not fulfilling its mandate.

As certification and continuing airworthiness projects are often complex and involve several members from different specialties, NAC would benefit from using project management information technology systems to assist with planning, scheduling, and tracking projects on a real-time basis and with managing workloads and performing trend analysis. As such, the NAC Program should implement its planned initiative to improve certification project management and also develop and implement a plan for continuing airworthiness project management. The NAC Program would also benefit from establishing specific outcomes and indicators to measure its performance.

Delegation is the process of authorizing technical experts, external to Transport Canada, to perform certification activities on behalf of the Minister of Transport. Delegates are authorized to issue some certification approvals on their own, with varying degrees of oversight from NAC.Footnote 38 The level of due diligence that NAC performs varies from delegate to delegate, based on the level of familiarity it has with the delegate, the delegate’s level of experience, and history. In most cases, the enterprise requiring certification of its aeronautical product is the employer of the delegate performing the certification activities, which presents an inherent conflict of interest. Like other global equivalent certification authorities, the NAC delegation process is based on a review of the delegates’ experience and the trust that the certifying authority has of the delegate. The NAC Program provides direct oversight of the delegates’ work during the certification process. Additional safeguards are employed to mitigate the risks of business pressures, such as timelines and budgets, coming in conflict with regulatory interests.

Continued monitoring and strengthening the safety cultures of enterprises, their delegates as well as the NAC organization would help to maintain the effectiveness of existing safeguards. This could include fully implementing the new voluntary Safety Management System (SMS) program and developing an approach to monitor attitudes and perceptions of NAC staff and delegates regarding the effectiveness of the safeguards in place to maintain delegate objectivity. Consideration could also be given to dedicating more effort to the delegate surveillance inspections as delegates may be more willing to raise issues in interviews that are held outside of the regular certification process.

Following direction from the Standing Joint Committee on the Scrutiny of Regulations and the Department of Justice, surveillance findings of non-compliance can now be made only against the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs). This change impacts NAC’s delegate surveillance process as it does not have an associated CAR or mandatory SMS obligations; findings are instead made against compliance with delegates’ Procedures Manuals. This issue must be resolved to ensure the continued effectiveness of NAC’s oversight of delegates.

4. Management response and action plan

The following summarizes the review recommendations and management’s action plan to address them.

| Recommendation | Management action plan | Completion date | ADM responsible | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

NAC Program Human Resource planning and requirements: The NAC Program should conduct analysis to determine the short, medium and long-term demand for aircraft certification and create an HR strategy to meet NAC objectives. This should include finalizing technical competencies for the specialty groups and developing a formal learning curriculum to address NAC’s specific technical development needs. |

NAC management agrees the technical competency training requirements in ADM CAD 005 would benefit from being rendered more specific and associated to a formal development curriculum. In parallel, training and on-the-job training (OJT) will need to be formalized within that curriculum. NAC will undertake a review of current and future aircraft certification requirements in Canada and perform a workload analysis. The review will address short and long- term demands, capacities, and the effects of recent NAC restructuring. The activity will also include a review of the current HR strategy and the development of a new one which better addresses the identified gaps pertaining to technical competencies and the development of a learning curriculum, namely taking into account industry demand, and budgeting improvements. The aforementioned process reviews will be conducted under the auspices of the implementation of a Quality Management System. In order to address the ongoing challenges of staffing specialists within National Aircraft Certification, it may be necessary to explore novel measures, such as full-time remote work, or assessing the optimal geographic location for NAC’s main office. Additional resources will be sought to dedicate to the completion of this activity including permanent staffing to create a more robust quality management system (QMS). |

December 2024 |

ADM, Safety and Security |

| 2 |

NAC program guidance and tools: The NAC Program should complete its improvement initiatives underway to ensure guidance is kept current to help maintain consistent practices and procedures. This includes:

|

a. NAC Program management will coordinate with the Standards Branch to develop a plan for updating all NAC guidance documents. The guidance will be updated and specifically, the following activities will also be undertaken for:

b. NAC Program management will

|

December 2025 | ADM, Safety and Security |

| 3 |

NAC Quality Assurance (QA) and measuring outcomes: The NAC Program should complete the implementation of a Quality Management System (QMS) unit. It should also leverage current departmental performance measurement work to assist in developing an approach to define specific NAC Program outcomes and indicators to measure performance. |

NAC Program management will ensure that:

Additional resources will be redeployed and sought to dedicate to the completion of this activity including permanent staffing to create a more robust quality management system (QMS). |

December 2025 | ADM, Safety and Security |

| 4 |

NAC project management: The NAC Program should implement its planned initiative to improve certification project management and develop and implement a plan for continuing airworthiness project management. |

NAC Program management will:

|

December 2022 | ADM, Safety and Security |

| 5 |

Strengthening and monitoring safety culture: The NAC Program should continue to promote and monitor the safety culture of the enterprises and the delegates they oversee, as well as its own staff. This should include fully implementing the new voluntary SMS program and developing an approach to monitor attitudes and perceptions of NAC staff and delegates regarding the effectiveness of the safeguards in place to maintain delegate objectivity. Consideration should also be given to dedicating more effort to the delegate surveillance inspections as delegates may be more open to raising issues outside of the regular certification process. |

NAC Program management will:

|

December 2022 | ADM, Safety and Security |

| 6 |

Delegation surveillance Findings of non-compliance: TCCA must resolve the issue created by a recent change that requires surveillance findings of non-compliance be made against CARs, and not manuals, to ensure the continued effectiveness of NAC’s oversight of delegates. |

NAC Program management will:

Additional resources will be redeployed and sought to dedicate to the completion of this activity including permanent staffing to create a more robust quality management system (QMS). |

December 2021 | ADM, Safety and Security |

Annex A – List of certification project categories

HQ:

- Initial (new) Type Design Certification (domestic and foreign): most often for Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) for new aeronautical products. The Director, NAC is ultimately accountable for the certificates held by these manufacturers. The overall certification process, from pre-application to approval, may take several years with HQ working closely with the manufacturer throughout.Footnote 39

- Subsequent Changes to Type Design (ongoing revisions):

- Derivative: amendment of an existing Type Certificate to add a new model (e.g. addition of seats to accommodate additional passengers in an aircraft and all associated changes (cockpit, control services))

- Post Type Certification Design Change, Major: Significant Change: configuration and/or construction has changed (e.g. aircraft will have 3 engines instead of 2)

- Post Type Certification Design Change, Major: Not Significant Change: configuration and/or construction has not changed (e.g. design weight increase, steep approach, high elevation air field operation)

- Substantial Change (very rare): extensive change that requires an application for approval of a new product (Type Design), rather than a changed product, and a complete demonstration of compliance (e.g. changes in design, configuration, power or weight of the product, including, in the case of an engine, its power limitations)

Minor Change: the change does not contribute materially to the level of safety. TCCA is not involved; rather, the design approval holder processes & approves the change.

RegionsFootnote 40:

- Supplemental Type Certification: generally for “third party” modifications (by companies other than OEMs) on aeronautical products (in their region) that already hold a Type Certificate (smaller manufacturers modifying/customizing other people’s aircraft i.e. camera mounts on helicopters). As required, NAC will provide technical specialist guidance.

- Repair Design Approval: to restore an aeronautical product back to its original design by OEM or operator

- Part Design Approval: a replacement part that will be installed on an aeronautical product

HQ and Regions: depending on where the OEM is located:

- Canadian Technical Standard Order (CAN-TSO) Design Approval: with respect to an appliance or part (e.g. OEM designs a GPS to be compatible with multiple aircraft models, obtains approval of GPS as a standalone, then markets it as TSO-certified)

Annex B – List of acronyms

- AAIR

- Annual Airworthiness Information Report

- AC

- Advisory Circular

- ACCT

- Aircraft Certification Consultation Team

- AD

- Airworthiness Directive

- AEOs

- Airworthiness Engineering Organizations

- ANAC

- Brazil National Civil Aviation Agency

- AP

- Authorized Persons

- AWM

- Airworthiness Manual

- BASA

- Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreements

- CAD

- Civil Aviation Directive

- CAN-TSO

- Canadian Technical Standard Order

- CAR

- Canadian Aviation Regulations

- CAW

- Continuing Airworthiness

- CAWIS

- Continuing Airworthiness Web Information System

- CMT

- Certification Management Team

- COI

- Conflict of Interest

- COVID-19

- Corona Virus 2019

- CRSM

- Cost Recovery Service Management

- DAO

- Design Approval Organization

- DAR

- Design Approval Representative

- DIS

- Delegate Information System

- EASA

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency

- FAA

- Federal Aviation Administration

- HQ

- Headquarters

- HR

- Human Resources

- ICAO

- International Civil Aviation Organization

- IT

- Information Technology

- JATR

- Joint Authorities Technical Review

- LOA

- Letter of Authorization

- LOI

- Level of Involvement

- NAC

- National Aircraft Certification Program

- NAPA

- National Aeronautical Product Approval System

- OEM

- Original Equipment Manufacturer

- PDP

- Personal Development Plan

- PED

- Planning Environment Document

- PIP

- Performance Information Profile

- PTS

- Project Tracking System

- QA

- Quality Assurance

- QC

- Quality Control

- QMS

- Quality Management System

- RDIMS

- Record, Document and Information Management System

- S&S

- Safety & Security

- SDR

- Service Difficulty Report

- SI

- Staff Instruction

- SOP

- Standard Operating Procedure

- TCCA

- Transport Canada Civil Aviation

- TSO

- Technical Standard Order