Transportation in Canada 2018

(PDF, 4.9 MB)

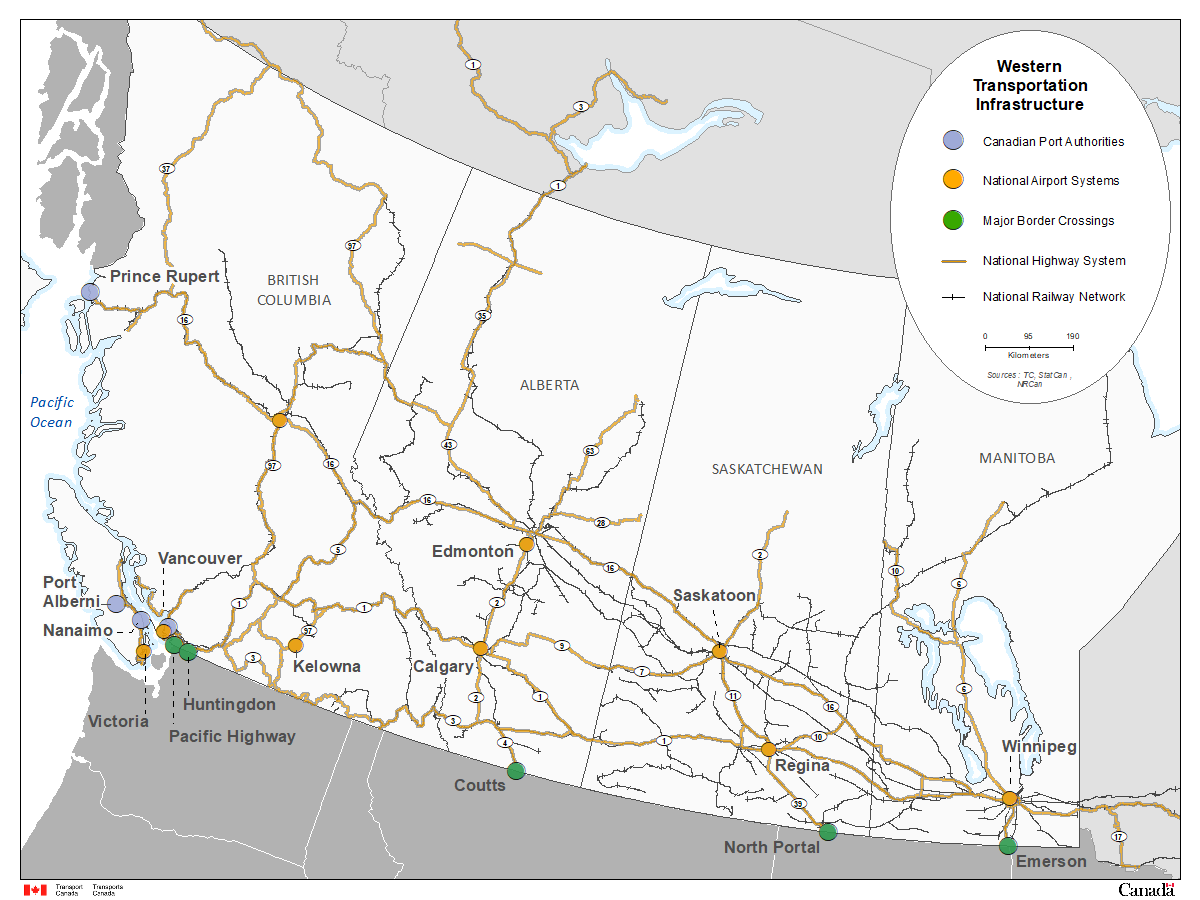

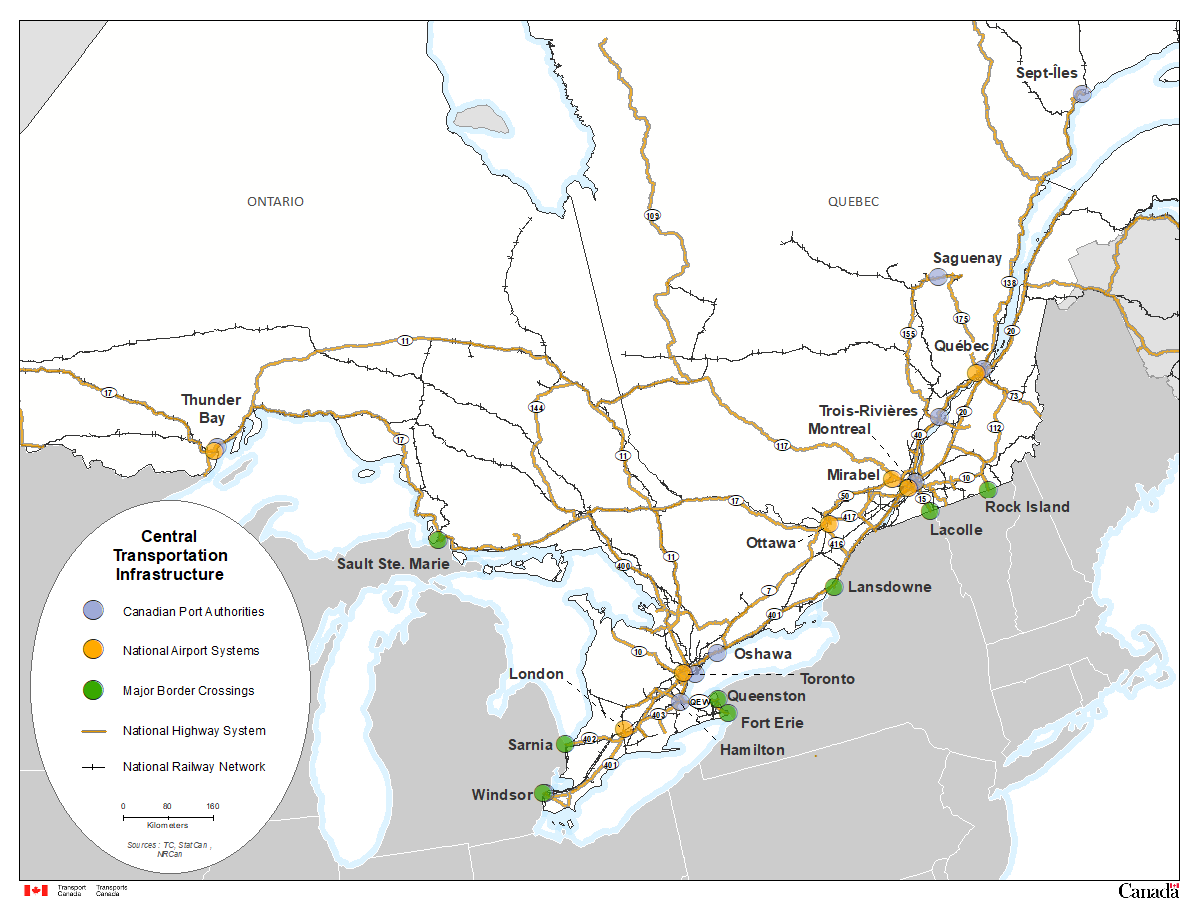

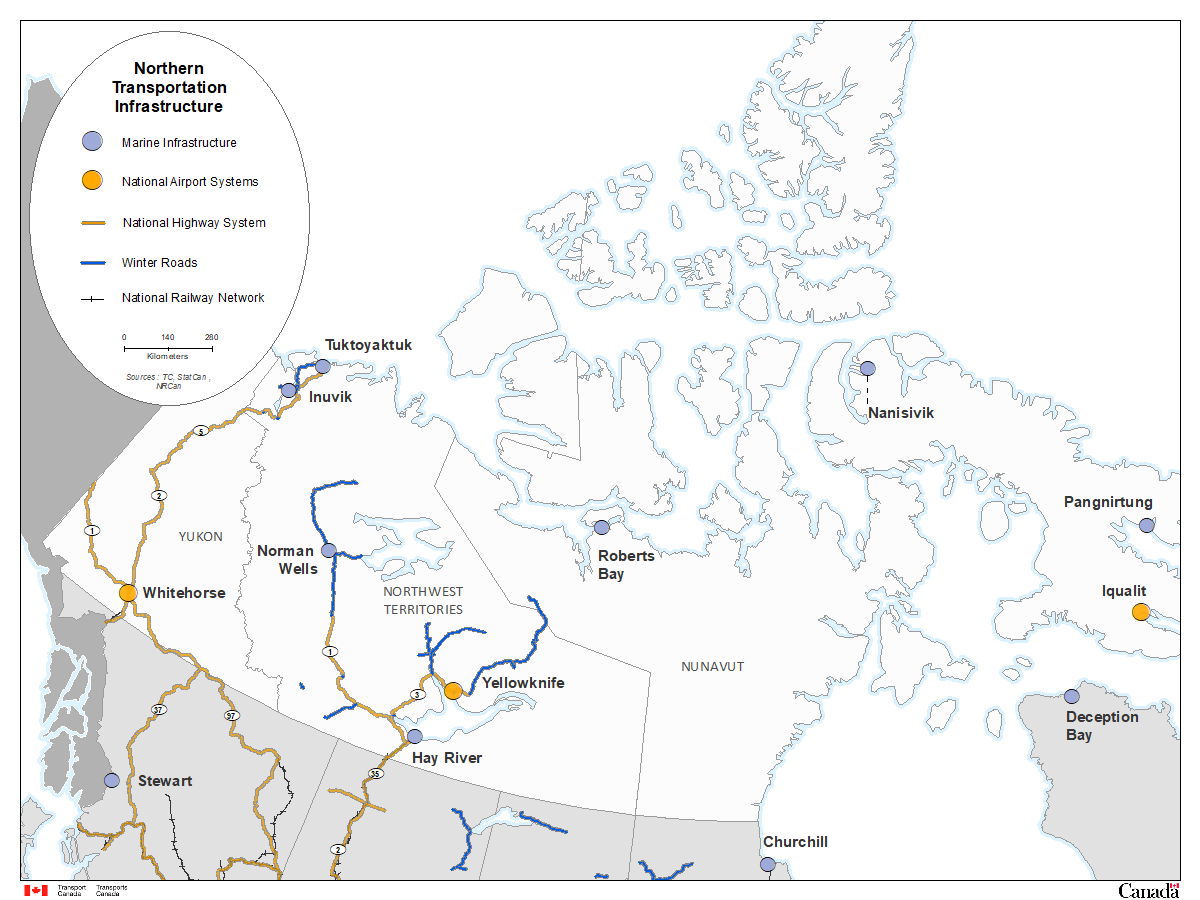

Image description - National Transportation Infrastructure of Canada

The map shows Canada’s transportation network, i.e. air, marine, rail and road transportation networks. It shows each of the 26 airports of the National Airport System (NAS). Each airport, represented by a black plane in a white circle, is identified geographically to illustrate basic air infrastructure. Seven of these airports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, three in Québec, four in Ontario, six in the Prairie Provinces and three in British Columbia. Three other airports are found in the capital of each territory.

It also shows the approximate location of the 18 Canadian Port Authorities (CPA). Each is represented by an anchor in a blue circle. The CPA ports are (in alphabetical order): Belledune, Halifax, Hamilton, Montréal, Nanaimo, Oshawa, Port Alberni, Prince-Rupert, Québec, Saguenay, Saint John, Sept-Îles, St. John's, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Trois-Rivières, Vancouver Fraser and Windsor. Four of these ports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, five in Québec, five in Ontario and four in British Columbia.

The map of Canada also shows the layout and extent of the Canadian rail system. This system currently has over 45,000 route-kilometres of track. The network is illustrated by orange lines for a geographical representation of rail infrastructure.

Finally, it shows the location of the National Highway System (NHS). The NHS includes over thirty-eight thousand kilometers of Canada’s most important highways from coast to coast. It is illustrated by blue lines for geographical representation of basic road infrastructure.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Transport, 2019.

Cette publication est aussi disponible en français sous le titre Les transports au Canada 2018, Un survol.

TP No. 15414 E

TC No. TC-1006321

Catalogue No. T1-21E-PDF

ISSN 1920-0846

Permission to reproduce

Transport Canada grants permission to copy and/or reproduce the contents of this publication for personal and public non-commercial use. Users must reproduce the materials accurately, identify Transport Canada as the source and not present theirs as an official version, or as having been produced with the help or the endorsement of Transport Canada.

To request permission to reproduce materials from this publication for commercial purposes, please complete the following web form or contact TCcopyright-droitdauteurTC@tc.gc.ca.

On this page

- Minister's Message

- Transportation 2030

- Highlights

- Report Purpose

- Chapter 1 The role of transportation in the economy

- Chapter 2 Overview of Canada’s transportation system

- Chapter 3 Air transportation sector

- Chapter 4 Marine transportation sector

- Chapter 5 Rail transportation sector

- Chapter 6 Road transportation sector

- Chapter 7 Transportation of dangerous goods

- Chapter 8 Performance of the Canadian transportation system in 2017

- Annex A: Maps and figures

- Annex B: List of addendum tables and figures

Minister’s Message

It is with great pleasure that I present Transportation in Canada 2018 to Canadians.

This annual report provides an overview of the state of the Canadian transportation system and describes recent developments in transportation policy.

The Government of Canada has an ambitious vision to make our transportation system safe, secure, more efficient and environmentally sustainable. Transport Canada built on last year’s momentum and worked diligently to realize this vision. We made substantial progress on key initiatives aligned with our Transportation 2030 Strategic Plan.

In 2018, amid growing demand, our transportation system stayed among the most competitive in the world. Our safety and security record was superb. Canada also continued its efforts to implement measures under that will reduce emissions from transportation.

We are making significant progress implementing the $1.5 billion Oceans Protection Plan to keep Canadian waters and coasts safe and clean for today’s use and for future generations. In partnership with Indigenous and in collaboration with coastal communities and stakeholders, this Plan will develop a world-leading marine safety system that will meet the unique needs of Canada, enhance its capacity to prevent, and improve response to marine pollution incidents from coast-to-coast-to-coast. We have announced initiatives worth more than $800 million under the Plan and have made significant progress under all four pillars. As part of the Oceans Protection Plan, we amended the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 and the Marine Liability Act to strengthen marine environmental protection and response. Building on the Oceans Protection Plan, we have also introduced measures to address key threats to endangered whale populations in Canada.

Enabling domestic and international trade was also a key priority. We announced funding for 39 projects under the National Trade Corridors Fund, an $800 million investment in infrastructure. Over the remainder of the program, we will invest more than $1 billion. Through this fund, we are improving transportation, growing the economy, diversifying trade and creating quality jobs to support the middle class.

Following extensive consultations, the Air Passenger Protection Regulations were announced on May 24, 2019. The regulations will ensure airlines provide better information and compensation to passengers as well as offer better treatment in case of delays.

Keeping Canadians safe is always our highest concern. This year, Transport Canada took action to address fatigue in aviation by introducing new science-based Flight Crew Fatigue Management regulations. We also launched new regulations for the use of drones to accommodate innovation while protecting the safety of Canadians. Safety measures were also put in place to address the risks laser attacks pose to aircraft air crews and passengers.

The federal, provincial and territorial Ministers also agreed to continue working together to explore potential measures to strengthen school bus safety, including the installation of seat belts.

Improving the lives of Canadians also means reducing environmental impacts of transportation. Through the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, we continue to support a clean fuel standard, research on clean transportation technologies, pan-Canadian carbon pricing and a zero-emission vehicles strategy.

In the coming year, we will continue our efforts towards a smarter, cleaner, more secure and safer transportation system that supports economic growth, the well-being of Canada’s middle class, and our position in the global market. We will also continue to lead in applying gender equity to our policies, programs and services.

I hope this edition of the annual report will increase interest in Canada’s transportation system, promoting a larger conversation on the issues Transport Canada works on every day.

Sincerely,

The Honourable Marc Garneau, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Transport

Transportation 2030

Transportation Modernization Act

On May 23, 2018, the Transportation Modernization Act received Royal Assent. This was the first legislative step to deliver on early measures in support of Transportation 2030. The act improved the transportation system in the following ways:

- Created a clear set of rules about how airlines in Canada must treat passengers

- Changed passenger airline ownership rules and introduced a more stream-lined approach to the consideration of joint venture applications to result in greater competition leading to lower air fares

- Allowed airports to pay for additional services to improve the security screening experience for passengers

- Put recording devices in locomotives to provide information about railway accidents, while protecting the privacy of railway employees

- Allowed foreign ships to move empty containers between places in Canada without a special licence, addressing the current shortage of containers available for export and reducing the cost of trade

- Allowed Canadian Port Authorities to access funding from the Canada Infrastructure Bank

Transportation 2030

The government of Canada’s strategic plan for the future of transportation in Canada.

Transport Canada continues to make progress in implementing Transportation 2030, a strategic plan for a safe, secure, green, innovative and integrated transportation system that supports trade and economic growth, a cleaner environment and the well-being of Canadians. Transportation 2030 is based on 5 themes:

- the Traveller

- Green and Innovative Transportation

- Trade Corridors to Global Markets

- Waterways, Coasts and the North

- Safer Transportation

Transport-related initiatives

This year, Transport Canada initiated and continued to develop a number of activities to support Transportation 2030.

The Oceans Protection Plan

$1.5 billion over five years to improve marine safety and responsible shipping, protect Canada’s marine environment, and offer new possibilities for Indigenous and coastal communities.

National Trade Corridors Fund

$2 billion over 11 years to strengthen Canada’s trade infrastructure (ports, waterways, airports, bridges, border crossings, rail networks).

Modernize Canada’s transportation system

Developing strategies, regulations and pilot projects to safely adopt automated and connected vehicles, and remotely piloted aircraft systems.

Canadian Centre on Transportation Data

Providing a one-stop location for high-quality, timely and accessible transportation data and information. Supporting evidence-based decision-making by addressing transportation data gaps, strengthening partnerships, and increasing the transparency of strategic transportation information. Includes the Trade and Transportation Information System.

The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change

Developing measures such as the federal carbon pricing system and clean fuel standard. Conducting research and testing on clean transportation technologies for all modes of transportation.

Highlights

Government of Canada actions

In 2018, Transport Canada continued multiple initiatives to advance its Transportation 2030 strategic plan. A fundamental part of this plan is the Transportation Modernization Act, which received Royal Assent in May 2018. This act will contribute to improve the safety and efficiency of the rail system and enhance the air passenger experience.

In addition, Transport Canada continued to implement other key initiatives. This included various measures under the national Oceans Protection Plan to protect Canada’s coasts for future generations, and the National Trade Corridors Fund, aimed at strengthening and increasing the efficiency of transportation corridors within Canada and to international markets. In 2018, the second and third National Trade Corridors Fund calls for proposals were announced, for projects located in the North and projects supporting trade diversification.

Transport Canada also took action to increase the safety and security of the transportation system. In March 2018, the Strengthening Motor Vehicle Safety for Canadians Act came into force. To help ensure road safety, the amendments introduced by this act will give more enforcement and compliance authorities to the Minister of Transport. The statutory review of the Railway Safety Act was also tabled in Parliament in April 2018. It concluded that the current rail safety legislation is sound and Canada’s rail transportation system is getting safer. In the air sector, the department took action to improve fatigue management based on the most recent research, and put safety measures in place to mitigate the risk laser strikes pose to aircrafts. Transport Canada also reinforced safety during the transportation of dangerous goods, notably by accelerating removal of the least crash-resistant rail tank for crude oil.

In 2018, the Government of Canada continued its efforts to reduce the environmental impacts of transportation. For example, regulations amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Greenhouse gas emissions from International Aviation – CORSIA) came into force on January 1, 2019 and require monitoring, reporting and verifying of greenhouse gas emissions as a first stage of implementing the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation in Canada. Throughout 2018, the federal government also continued to work with provinces and territories on the development of a Canada-wide strategy for zero emission vehicles.

To better protect Southern Resident killer whales, further measures to reduce underwater noise and vessel monitoring were announced and implemented. Speed management measures were also put in place in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to reduce risks to North Atlantic right whales.

Transportation volumes and performance

In 2018, the transportation system was able to adjust overall to favourable economic conditions, which translated to increased demand for Canadian merchandise abroad, and for international goods transiting or consumed domestically.

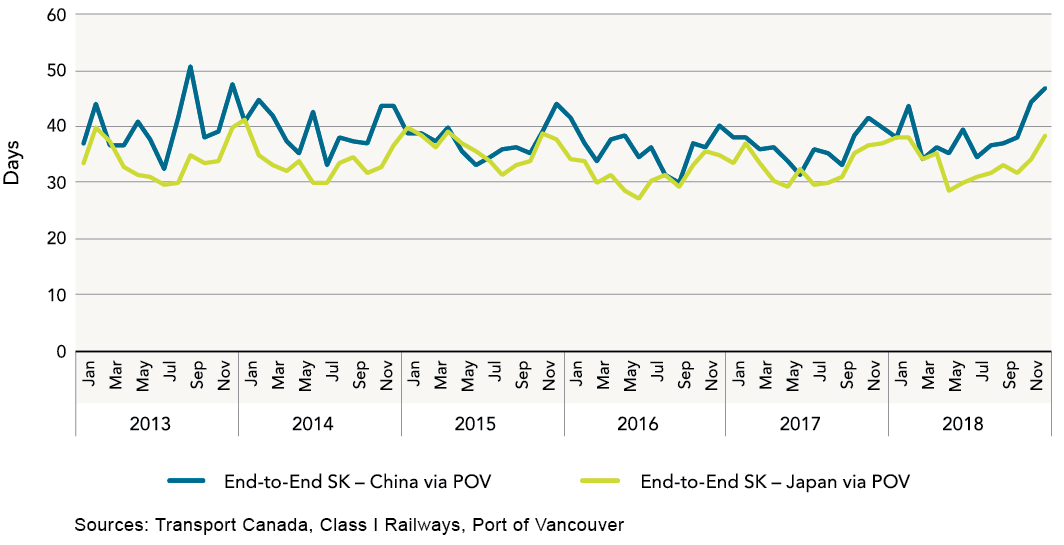

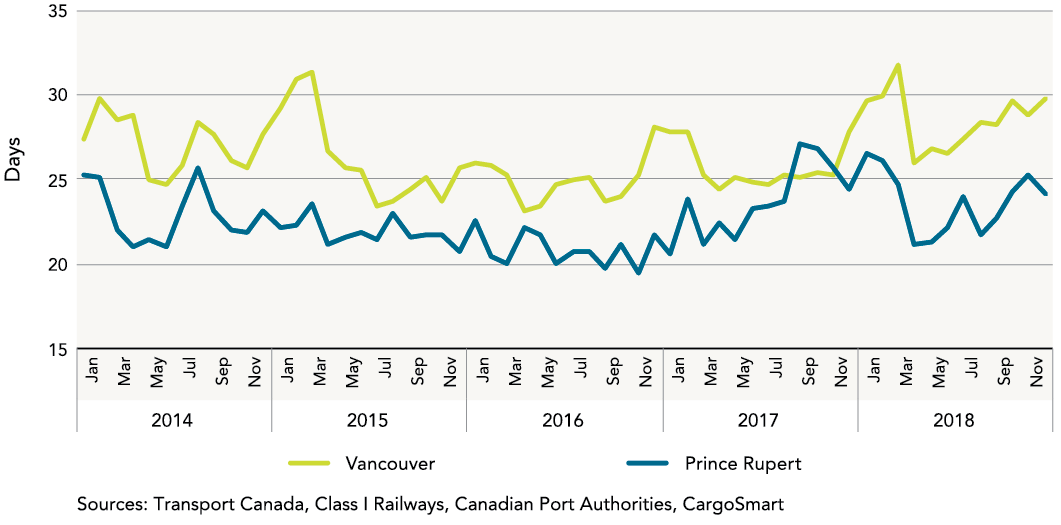

Total freight tonnage moved increased in 2018. Rail traffic volume reached an all-time high, driven by containerized cargo, crude oil, potash, and petroleum products (excluding crude oil). Similarly, the value of international waterborne traffic also increased, as did volumes handled at most major Canadian ports (Vancouver, Prince Rupert, Montréal and Halifax).

Overall, the transportation system responded effectively to higher transportation demand. However, challenging winter weather conditions, operational issues and multiple outages resulted in congestion challenges in various parts of the network. This was especially the case in the Vancouver Lower Mainland, where grain, potash and forest supply chains were notably impacted. Based on performance metrics produced by Transport Canada, intermodal and grain supply chain transit times were noticeably longer in 2018 compared to previous years’ average. Stakeholders have been working in close collaboration to better understand and tackle capacity and performance challenges through the Commodity Supply Chain Table.

The number of international passengers moved across all modes set a new record high of 21.1 million trips of one or more nights. The number of air passengers travelling domestically and internationally also increased significantly.

Environment, safety and security

From 2005 to 2016, greenhouse gas emissions from the transportation sector increased by 7%. However, there have been some notable improvements when looking at individual modes specifically. For instance, the emissions intensity of freight rail has decreased by over 40% since 1990. The emissions intensity of Canadian air carriers has decreased by 15.6% between 2008 and 2017. Despite fuel efficiency improvements, emissions from road transportation, which represents 21% of total Canadian greenhouse gas emissions, have increased by 12% from 2005 to 2016, largely due to an increase in the number of vehicles on the road and greater reliance on heavy duty trucks.

Canada continues to have one of the safest and most secure transportation systems in the world. Road casualty collisions decreased over the last ten years, although more vehicles were on the road. In marine transportation, the number of accidents involving at least one Canadian-registered vessel was lower than the ten-year average, similarly, the number of aviation accidents was lower than the five-year average. However, the number of railway accidents in 2018 was slightly higher than the ten-year average.

Transportation outlook

Over the next ten years, decelerating global and Canadian economic activity is expected to result in a slowdown in overall trade, tempering transportation demand. More specifically, rail transportation demand for key bulk Canadian commodities is expected to remain stable. However, traffic to the West Coast is expected to increase at a sustained pace, reflecting the growing demand of Canadian goods from Asian markets.

Canada’s air passenger traffic is expected to increase over the next decade but at a slightly slower pace than over the previous decade. This growth will largely be driven by increased economic activity and persistently declining real prices for air transportation.

Report purpose

Transportation is a major contributor to Canada’s economic growth. It facilitates the movement of goods and people, allows for greater economic opportunity and contributes to trade diversity. It also helps enhance Canadians’ standard of living by supporting both economic growth and mobility. However, because of Canada’s unique features, transportation comes with challenges. Canada’s population density, four people per square kilometre, is much lower than the average of 33 people per square kilometre for high-income countries. Our weather, which varies greatly from one season or location to another, can affect transportation efficiency and make performance uneven across the country and the year. In this context, monitoring and reporting on the state of the transportation system leads to better diagnostics and tailored solutions which, in turn, contributes to efficiency.

As mandated by the Canada Transportation Act of 2007, subsection 52, each year the Minister of Transport must table in both Houses of Parliament an overview of the state of transportation in Canada. This report, submitted by the Minister under the act, provides an overview of transportation in Canada based on the most current information for all modes of transportation at the time of publication.

The report highlights the role of transportation in the economy and offers an overview of the four transportation modes (air, marine, rail and road) in terms of infrastructure, safety and security, and environment. It describes major industry and policy developments in the transportation sector during 2018. It also presents a short overall assessment of the Canadian transportation system’s performance in 2018, looking at the system’s use and capacity. The report concludes with an outlook on expected trends in freight and air passenger transportation.

A statistical addendum to this report is also available. It has information on freight and passenger traffic for each mode, as well as infrastructure statistics. The transportation and economy section shows economic indicators, statistics on labour in the transportation industry, price and productivity indicators, and data on freight trade by mode and country. It also details reported accidents and greenhouse gas emissions.

More data and analysis are also available online through the Canadian Centre on Transportation Data and its Transportation Data and Information Hub (“the Hub”).

Canadian Centre on Transportation Data and Transportation Data and Information Hub

High-quality, timely and accessible information is key to supporting decision-making and policy-makers, as well as industry, and Canadians using the transportation system. Information helps address issues critical to making transportation more efficient, safer and environmentally sustainable.

Following the Government of Canada’s commitment to improve access to transportation data in its 2017 Budget, Transport Canada and Statistics Canada jointly launched the new Canadian Centre on Transportation Data (CCTD) in April 2018.

Through the Hub, the CCTD provides easy access to a comprehensive, timely and accessible source of multimodal transportation data and transportation system performance measures.

It also aims to facilitate discussions and foster collaboration among key stakeholders from both the public and private sectors, to identify synergies and efficiencies that will support better decision-making at all levels.

The first phase of the Hub was launched on April 13, 2018. This phase provides public access to over 600 transportation data sets, as well as traffic and performance indicators at the national level, interactive maps, and analytical reports and tools. The second phase of the Hub will include enhanced analytics, interactivity and visualization, as well as more detailed projections on future transportation demand to help make better investment decisions.

Transport Canada will continue developing the Hub to add new and relevant content for the transportation community. The longer-term goal is to share information that will contribute to effective decision-making in Canada, so as to take full advantage of the transportation system to support a strong economy.

Chapter 1 The role of transportation in the economy

Highlights

- The transportation and warehousing sector’s gross domestic product (GDP) increased 3.2%, 1.4 times the growth rate for all industries.

- Aggregate household expenditures on transportation (including insurance) amounted to $202.3 billion, second only to shelter.

- In 2018, total international merchandise trade was $1,178 billion, a 6.3% increase compared to 2017.

Transportation enabling economic growth

Transportation and warehousing is important to the Canadian economy. Traditional measures of gross domestic product (GDP) account only for the economic activities directly linked to for-hire or commercial transportation. However, transportation is also integral to activities not included in economic measures, such as the value of personal travel and of own-account transportation activity. Using the Canadian Transportation Economic Account (CTEA) 2014, the transportation sector contributed $153.4 billion or 8% of GDP.

In 2014, according to the CTEA, household production of transportation services increased the total Canadian GDP by $58.3 billion. Non-transportation industries (e.g. manufacturing, wholesale trade and construction) produced $41.5 billion of own-account transportation services, or 30% of the total domestic supply of transportation.

Using traditional measures of GDP, the sector represented 4.5% of GDP ($88 billion) in 2018. The sector grew 3.2% in real terms in the past year, nearly 1.4 times the growth rate for all industries. The compound annual growth rate for GDP in the transportation sector over the previous five years of 4.1% also exceeds that of the economy as a whole (2.1%).

In 2018, 920,800 employees (including self-employed people) worked in the transportation and warehousing sector, up 2.7% from 2017. In 2018, women held 24.5% of total employment in the transportation and warehousing industries. In comparison, they held 47.7% of total employment in overall industries.Footnote 1

Employment in the transportation and warehousing sector accounts for about 5% of total employment, a share that has remained stable over the past two decades. There were approximately 1.8 unemployed people with relevant work experience for every vacant job in the sector, compared to a ratio of 3.4 for the overall economy.

In 2018, workers aged 55 and older represented 27.5% of the transportation industry. In comparison, workers aged 55 and older represented only 21.3% of employment in all industries. The World Bank has reported that skill shortages in transportation and warehousing are a major threat for the sector. The aging workforce and upcoming retirement of baby boomers are expected to contribute to labour shortages in certain occupations.

In 2018, aggregate household final consumption expenditures on transportation (including insurance) amounted to $202.3 billion, second only to shelter in terms of major spending categories. Household consumption on transportation grew 2.9% annually on average over 2014 to 2018, while overall expenditures grew 2.6%. Household spending for personal travel accounted for about 11% of the GDP. Furthermore, federal and provincial government expenditures on infrastructure represented just under 1% of the GDP.

Transportation enabling trade

Transportation is essential for trade. It allows natural resources, agricultural products and manufactured goods to access domestic and international markets.

The value of interprovincial merchandise trade totaled $170 billion (current dollars) in 2017, up 8.5% from 2016.

In 2018, total international merchandise trade amounted to approximately $1.2 trillion, a 6.3% increase compared to 2017 and the highest value of total trade on record. The United States (U.S.) remains Canada’s top trade partner, with $741 billion in total trade ($438 billion exported, $304 billion imported), up 5.5% from 2017. The U.S. accounted for 63% of total Canadian trade in 2018, a stable share over the past ten years.

In addition to the U.S., Canada’s top five trading partners in 2018 included China, Mexico, Japan and the United Kingdom. The latter four nations accounted for 17.3% of Canada’s total international trade in 2018.

Transportation enabling mobility

According to the Statistics Canada’s 2016 census, people spent 5% of their day travelling to and from activities, which was equivalent to 1.2 hours.

The number of people commuting to work has increased by 30.3% from 1996 to 2016, reaching 15.9 million. In 2016, the average commuting time was 26.2 minutes, up nearly one minute from 2011. Since then, the number of workers who spent more than 60 minutes to commute to work increased by almost 5% due among other things to increased time spent in traffic.

In 2017, 85% of households owned, leased or used at least one vehicle. A significant share of households, 39%, owned two or more vehicles. Those numbers have remained fairly stable since 2010, with the share of households owning two or more vehicles rising slightly.

As for public transportation use, studies show that public transit is increasingly favoured by the younger population, with people under 30 using more public transit compared to previous cohorts within a similar age category. However, older people have been less inclined to use public transportation than previous cohorts, with baby boomers being strongly attached to their private vehicles.

Canadians travelled more in 2018. The number of person-trips to international destinations increased 19% from 2009. Although U.S. destinations are still the most popular international travel destination for Canadians, trips to other countries increased by 45% compared to 13% for U.S. destinations over the same period. When looking at Canada as a destination, tourism arrivals increased 21% over the last ten years. Land transportation has slowly decreased while use of air transportation has gone up.

Chapter 2 Overview of Canada’s transportation system

Highlights

- Canada’s transportation network efficiently connects cities and smaller communities over its vast and sparsely populated territories, from coast to coast to coast.

- In 2018, a second National Trade Corridors Fund call for proposals was launched, dedicated to projects located in the North. A third call for proposals, in support of trade diversification projects, was also announced.

- Looking ahead, Canada’s transportation network will continue to face a number of challenges—responding to growing Asian demand, adapting to climate change, integrating emerging technologies and connecting remote communities.

Canada’s economy relies on an efficient and competitive national transportation system. Budget 2017 detailed the Government’s 11-year, $186 billion Investing in Canada Plan for infrastructure. The Plan committed significant funding to trade and transportation, including by establishing the National Trade Corridors Fund.

National Trade Corridors Fund

- The $2 billion, 11-year National Trade Corridors Fund supports projects that result in stronger, more efficient transportation corridors, both within Canada and to international markets.

- The competitive, merit-based program invests in projects that address urgent capacity constraints and freight bottlenecks at major ports of entry, and that better connect the rail and highway infrastructure that delivers economic growth across Canada.

- NTCF projects also help the transportation system withstand the effects of climate change and ensure that it is able to support new technologies and innovation.

- Up to $400 million of the NTCF funding is allotted to projects that will address critical transportation needs in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon.

- There have been three calls for proposals for NTCF to date:

- The first NTCF call for proposals was launched in 2017. The Minister of Transport approved more than $800 million of NTCF funds for 39 projects that will improve the efficiency and resilience of ports, roads, railways, airports, and intermodal facilities across the country.

- A second NTCF call for proposals, dedicated to projects located in the territorial North, was launched in fall 2018. Projects will be assessed and announced in 2019.

- The 2018 Fall Economic Statement announced an Export Diversification Strategy to increase Canada’s overseas exports by 50% by 2025. It also accelerated the remaining NTCF funding for allocation over the next 5 years, instead of the original 11 years. The third NTCF continuous national call for project proposals was announced in late 2018, with explicit selection criteria for projects that will diversify and increase Canada’s trade with overseas markets. Project proposals will be accepted and assessed throughout 2019.

Canada’s national transportation network

Canada is the second largest country in the world by total geographic area, with close to 10 million km2, constituting a land area of around 9 million km2 and a population density of 3.9 people per km2. Considering Canada’s vast and sparsely populated territories, ensuring the safe, secure and efficient movement of goods and passengers is a formidable task. This section presents an overview of Canada’s transportation network, as well as some of the current and emerging challenges the system is facing.

For more detailed regional maps (1 to 4), refer to Annex A.

Canada’s national road transportation system

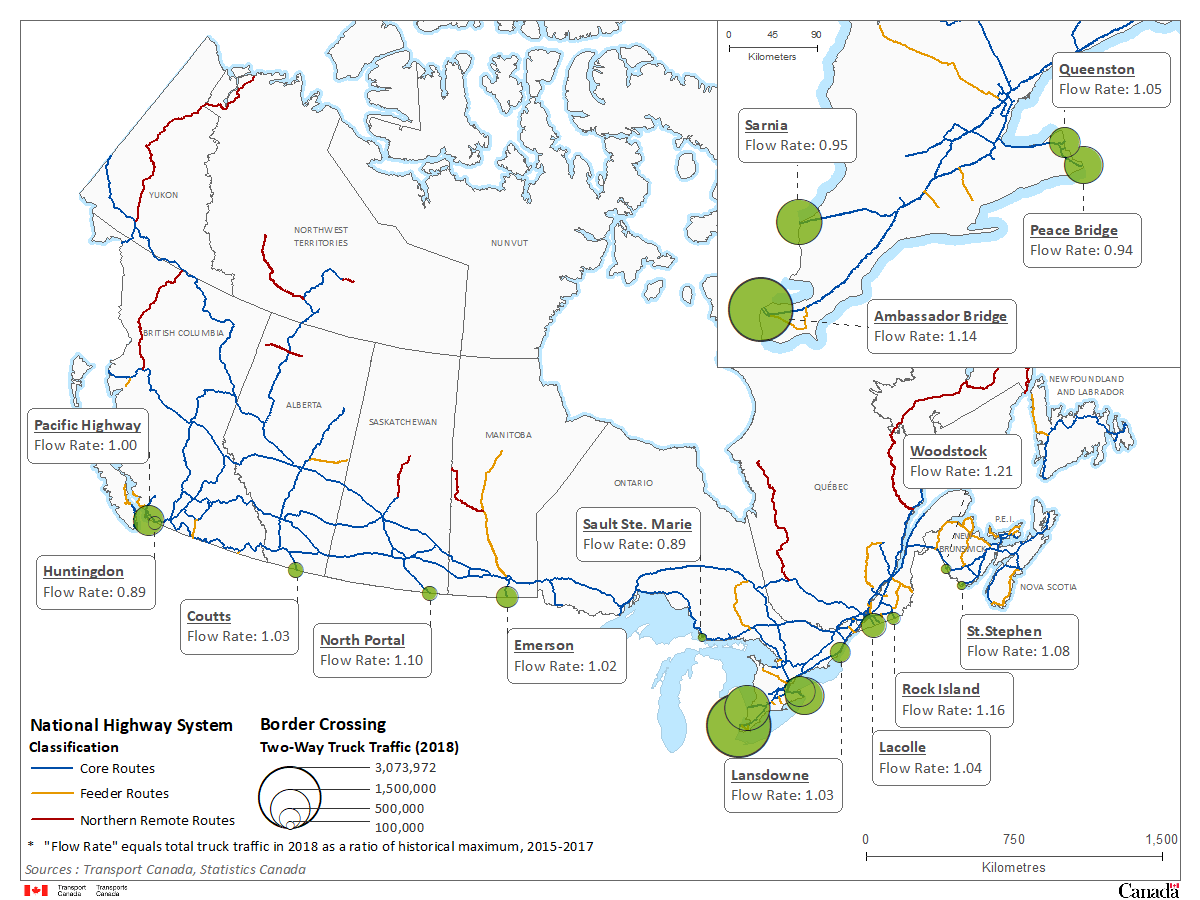

Road transportation is the dominant mode for moving both freight and passengers across Canada. Our country is linked from the Pacific to Atlantic coasts by a network of connecting highways anchored by the Trans-Canada Highway. Canada also has extensive road networks across its southern, more populated areas.

In Canada trucking is the primary form of freight transportation, most notably in central Canada, where it largely moves food products and higher valued manufactured and processed goods. Ontario and Québec also have the busiest road border crossings in Canada, especially in Ontario, where manufactured goods cross and re-cross the Canada-U.S. border several times throughout production. Canada and the U.S. have a highly interconnected supply chain, particularly in automotive manufacturing. In central Canada, 53% of total merchandise exports by value, excluding pipelines, were exported by road in 2018. This was compared to 32% and 19% in Canada’s Western and Atlantic regions, where exports rely on marine transportation more.

Yukon has the most extensive highway system in northern Canada, carrying the most northern traffic in tonnage terms. Some Northern communities, only reachable by barge or air for most of the year, also rely on ice roads during the winter to transport people and vital supplies.

Canada’s national rail transportation network

Canada’s rail operations help sustain nearly every part of the Canadian economy, including our manufacturing, agricultural, natural resource, wholesale and retail sectors, and tourism.

There are two major freight railways serving Canada’s network. Canadian National (CN) has a rail network of around 22,000 km of track across Canada, and an American portion extending to the Gulf Coast. Canadian Pacific (CP) has 12,900 km of track across Canada and track that extends into the U.S., south to Kansas City. A number of short line railways are also instrumental in transporting containerized merchandise and bulk resources to and from major ports and the U.S.

National rail passenger services are largely provided by VIA Rail on behalf of the Government of Canada. Via Rail is an independent Crown corporation operating coast to coast. Most of its services and infrastructure are located in central Canada along the Québec-Windsor Corridor. VIA Rail also operates long-haul passenger routes between Toronto and Vancouver and Montréal and Halifax, as well as regional services to destinations such as Jasper, Prince Rupert, Winnipeg and Churchill. In 2018, VIA Rail operated 474 train departures weekly on a 12,500 km network and transported a total of 4.7 million passengers.

Canada’s marine transportation network

Canadian ports are the main point of exit for our abundant natural resources, such as metallurgical coal, grains, fertilizers and forest products. These commodities are shipped to a broad array of overseas destinations, with a predominant and increasing focus on East Asian markets (China, Japan and South Korea) driven by rising demand for Canadian goods. Canadian ports are also the main point of entry for imported containerized manufactured goods, again dominated by the Asian market. Ports are important hubs, connecting Canadian coast lines to inland domestic and U.S. markets where goods are shipped by railways and trucks.

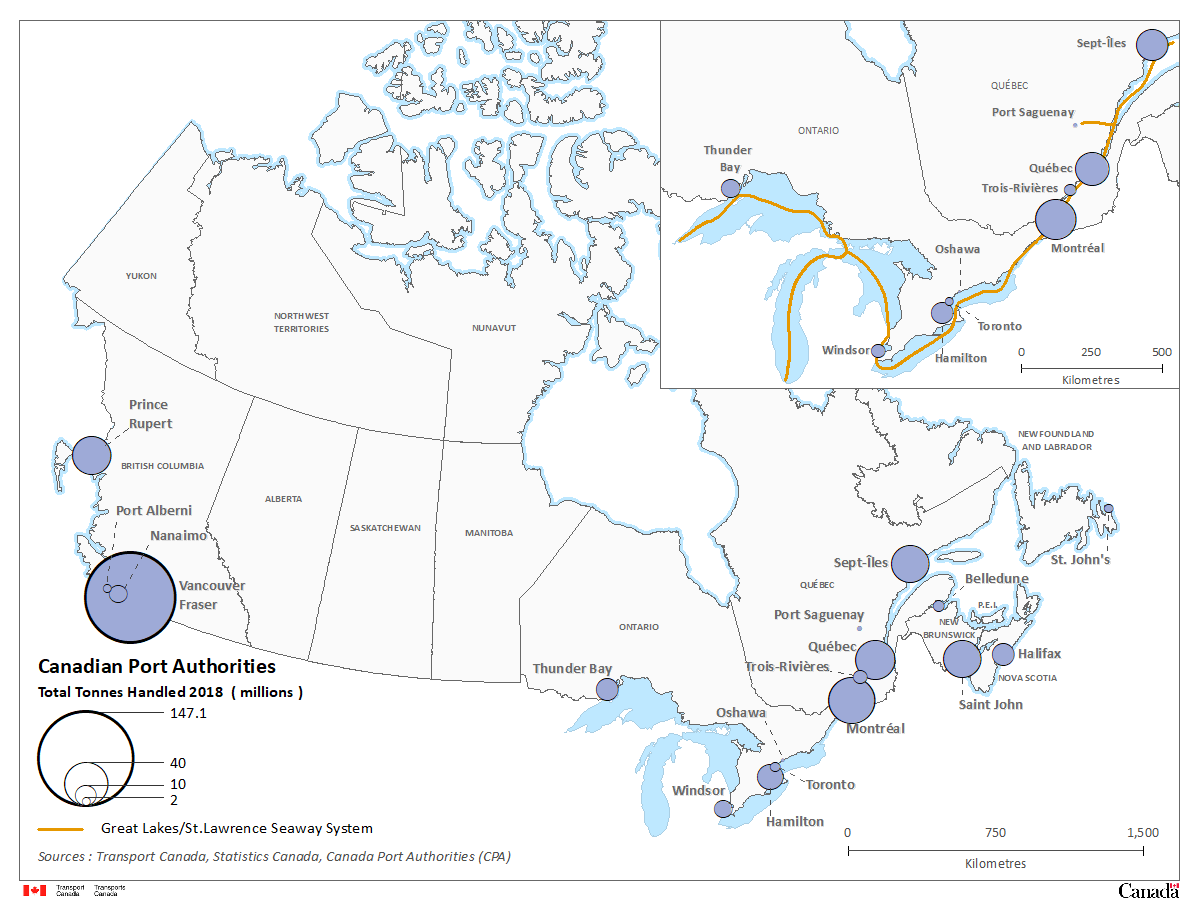

The Port of Vancouver, located on the southwest coast of British Columbia, is Canada’s largest port in terms of traffic volume. It handled 147.1 million tonnes of traffic in 2018, largely destined for and arriving from Asian markets. The Port of Prince Rupert, another important and growing port on the West Coast, handled 26.7 million tonnes in 2018. The Port of Prince Rupert is closer to Asia than other west coast ports in North America.

The Port of Montréal is Canada’s second largest container port, mainly serving Québec, Ontario and the U.S. Midwest. In 2018, the port handled more than 38.9 million tonnes of cargo from around the world, but mostly from Europe.

The Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Seaway (“the Seaway”) are also a key marine transportation asset. The Seaway provides waterway access into central Canada and the North American heartland, serving 15 major ports and 50 regional ports that connect to more than 40 provincial or interstate highways and 30 railway lines. In 2018, 40.4 million tonnes of product moved through the Seaway. The following products accounted for two-thirds of the traffic in 2018:

- grain (12.1 million tonnes)

- iron ore (7.3 million tonnes)

- salt (3.5 million tonnes)

- liquid petroleum (3.2 million tonnes)

The Port of Halifax is the largest container port in Atlantic Canada. It handles most of the region’s trade, with 4.8 million tonnes of total cargo in 2018. Moving petroleum products and vehicles is also an important part of the port activities.

The Port of Saint John in New Brunswick is Atlantic Canada’s largest port in terms of tonnage (25.1 million tonnes in 2018). Saint John is an important port for processing, refining and shipping crude oil.

Similarly, the Port of Come-by-Chance in Newfoundland and Labrador handles a large quantity of petroleum products from the province’s offshore oil development project sites.

Many remote northern communities are highly dependent on summer sealifts for their bulk transportation needs. Arctic sealift operations resupply coastal communities in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories with no permanent road connection to southern Canada. The sealift is characterized by a system of tanker and dry cargo ships resupplying Baffin, Kivalliq and Kitikmeot. It also includes deep draft barge to Kitikmeot and coastal Northwest Territories communities, and a barge system through the Mackenzie River.

Canada’s national air transportation network

Canada’s air transportation system integrates with the global economy and moves passengers across a country spanning over six time zones. Major Canadian airports include:

- Toronto’s Pearson Airport, Canada’s busiest, which moved 47.9 million passengers in 2018

- Vancouver International, which handled 24.9 million passengers in 2018

- Montréal’s Pierre-Elliot Trudeau, which moved 18.8 million passengers in 2018

In 2018, the top 20 busiest Canadian airports moved 141.8 million passengers.

International airports in each major city also provide cargo services to domestic and international markets. Major cargo airports included Toronto Pearson International Airport (490.1 thousand tonnes), Vancouver International Airport (343.9 thousand tonnes) and Hamilton Airport (107.2 thousand tonnes).

Air transportation is also crucial in Canada’s remote northern regions, where it provides residents a year-round link to southern Canada. Aviation is a crucial link to essential services such as medical emergencies, all-season resupply of food and mail, tourism, and other employment and economic development opportunities.

Canada’s key transportation challenges

Looking ahead, Canada’s transportation network will continue to face a myriad of current and emerging challenges, ranging from bottlenecks to climate-change-related disruptions. These challenges will test our ability to enable safe, secure and efficient movement of passengers and goods.

To take advantage of increasing trade and travel opportunities offered by emerging markets, notably in Asia, Latin America and Africa, Canada’s transportation network needs to efficiently adapt to growing demand. In western Canada, episodes of congestion on the rail network and at ports have recurred over past years, particularly in the Lower Vancouver Mainland in the context of more Asian demand for Canadian commodities and operational issues. High and increasing traffic volume in this area, combined with physical constraints due to the surrounding urban area, impede expansion of network capacity and economic growth. Increasing physical capacity is challenging, which raises the need to optimize our existing assets, ensure all supply chain stakeholders are coordinated, and consider the most efficient model of governance.

Adapting our transportation system to the impact of climate change is also a challenge for Canada. Extreme weather-related events such as tornadoes and heavy precipitation, and more gradual climate change impacts such as permafrost thaw and coastal erosion, represent risks for the network. These vulnerabilities are putting additional pressures on transportation supply chain capacity and affecting efficiency. Transportation infrastructure will need to be more resilient. Status quo could be costly for the Canadian economy. Climate change has already had financial impacts on Canada and these costs are expected to continue growing.

In many remote and Northern communities, providing transportation services poses serious challenges. Across most of Canada’s territories, population is sparsely distributed. Harsh weather conditions, more rapid climate warming, and limited infrastructure make it difficult and costly for transportation operators to provide a reliable level of services. Nevertheless, these regions often present great economic opportunities. Canada needs to ensure these communities are connected to our national network.

In contrast to remote communities, different modes of transportation come together in densely populated urban areas. Large Canadian cities share the same traffic congestion challenges as urban centres around the world. Urban congestion generates personal and environmental costs, and also negatively impacts the national economy due to lower productivity levels and supply chain delays along the first and last miles.

Existing and emerging technologies are also shaping the future of transportation, including artificial intelligence, 3D printing, and advances in automation, robotics and intelligent transportation systems. Canada’s use of and reliance on technology has accelerated rapidly over the past few decades, along with its importance to the transportation system. If these technologies are integrated into Canada’s new and existing infrastructure, they have great potential to increase transportation capacity and change the relative costs of shipping for all modes of transportation. As well, governments must continue to act early in developing policies and regulations that harmonize with the U.S. and other international destinations.

Chapter 3 Air transportation sector

Map: Air transportation network

Image description: Air transportation network

The map of Canada shows the 26 airports of the NAS. Each airport, represented by a black plane in a white circle, is identified geographically to illustrate basic air infrastructure. Seven of these airports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, three in Québec, four in Ontario, six in the Prairie Provinces and three in British Columbia. Three other airports are found in the capital of each territory.

Highlights

- Canada continued to build on air transport agreements with over 100 bilateral partners, and explored avenues for new connections and agreements. The Transportation Modernization Act received Royal Assent in 2018. This act will:

- Improve how Transport Canada reviews joint venture applications

- Allow Canadian air carriers to access greater investment from international investors

- Lead to clearer, fairer rules for passenger rights

- After extensive consultations, the Government of Canada established new prescribed flight and duty limits, grounded in modern science, to make Canada’s aviation sector safer.

- New aviation regulations that require monitoring, reporting and verifying of emissions came into force as of January 1, 2019. These regulations are set to begin in 2019.

Industry infrastructure

Canada is the world’s third-largest aviation market, with 18 million km2 of airspace managed by NAV CANADA.

NAV CANADA is a privately run, not-for-profit corporation that owns and operates Canada’s civil air navigation system. It operates air traffic control towers at 40 airports and flight service stations at 55 airports.

For a detailed representation of National Airport System Airports, refer to Map 5 in Annex A.

The Canada Flight Supplement and Canada Water Aerodrome Supplement listed 1,545 certified and registered sites in 2018. The sites fall into three categories:

- 225 water aerodromes for float and ski planes

- 321 heliports for helicopters

- 999 land aerodromes for fixed-wing aircraft

Industry structure

In 2018, 6.5 million aircraft movements took place at airports, 3.7 million of which were made by airlines. General aviation companies made the other 2.8 million, which were itinerant and local.Footnote 2

In 2018, Canada had:

- 36,723 Canadian registered aircraft

- 53,479 licensed pilots

- 2,201 licence authorities, held by 1,408 air carriers operating in Canada (41% Canadian and 59% foreign)

Canada also had:

- 18,098 aircraft maintenance engineers

- 864 approved maintenance organizations

- 483 certified and 1,062 non-certified aerodromes.

Legislative developments

On May 23, 2018, the Transportation Modernization Act received Royal Assent. Among other things, this act amends the Canada Transportation Act. Three of the amendments impacted air transportation, including:

- A new, voluntary process for assessing and authorizing air carrier joint venture applications

- Broadening of the investment capital pool available to Canadian air carriers that offer passenger or all-cargo air services, by permitting non-Canadian investors up to 49% in their voting interests

- An authorization for the Canadian Transportation Agency to make regulations setting out air passenger rights, including levels of compensation should those rights be breached

- Allowing airports to pay for additional services to improve the security screening experience for passengers

Air Canada

In 2018, Air Canada’s domestic network, operated by its mainline and Air Canada Express, accounted for 55% of available seat-kilometres in the domestic air market.Footnote 3 Footnote 4

Air Canada, Air Canada Express and Air Canada Rouge operated an average of 1,613 scheduled flights per day. The Air Canada network has three hubs (Toronto, Montréal and Vancouver). It provided scheduled passenger services to 64 Canadian destinations, 60 U.S. destinations and 98 other foreign destinations on six continents.

As of December 2018, Air Canada had a fleet of 184 aircraft, while Air Canada Express operated 154 aircraft and Air Canada Rouge operated 53 aircraft. During that month, Air Canada also re-acquired Aeroplan, one of Canada’s largest loyalty rewards programs. Aeroplan was separated from Air Canada and divested in 2004 after the company was reorganized while operating under protection from bankruptcy.

WestJet

In 2018, WestJet and WestJet Encore accounted for 36% of available seat-kilometres in the domestic air market.

WestJet and WestJet Encore operated an average of 712 scheduled flights per day. They provided scheduled passenger services to 40 Canadian destinations, 27 U.S. destinations and 38 other foreign destinations. As of January 2019, WestJet had a fleet of 126 aircraft, while WestJet Encore operated 47 aircraft.

Northern air carrier industry

On September 28, 2018, Makivik Corporation and Inuvialuit Development Corporation agreed to merge two of their operating companies, Bradley Air Services Ltd. doing business as First Air and Canadian North Airlines Inc., subject to federal approval.

This agreement would result in First Air acquiring and then merging with Canadian North to form a single Pan-Arctic air carrier, Canadian North. The proposed merger follows a failed merger attempt in 2014 and a code share during 2015 to 2017, between First Air and Canadian North. On November 13, 2018, the Minister of Transport launched an assessment by Transport Canada of the proposed merger, largely because the two air carriers provide most scheduled air services to Canada’s high Arctic region. This assessment, along with an assessment by the Commissioner of Competition, will inform the federal government’s decision on whether to approve the merger.

Other carriers

In 2018, Porter Airlines, a regional carrier based at Toronto’s Billy Bishop airport, used a fleet of 29 turboprop aircraft to provide direct, non-stop scheduled passenger services to 16 destinations in Canada and 7 in the U.S.

Air Transat was the largest leisure carrier in Canada for 2018, with a fleet of up to 48 aircraft, depending on the season. Air Transat served 64 international destinations in 28 countries.

Sunwing Airlines is Canada’s second largest leisure carrier. It operated over 40 aircraft, depending on the season, and served 33 international destinations in 12 countries.

In April 2018, Exchange Income Corporation (EIC), a publicly traded holding company, took an undisclosed stake in Wasaya Airways. Wasaya Airways is an operating company of Wasaya Group, also a holding company and owned by 12 First Nations. EIC’s aviation portfolio also includes Perimeter Aviation (including its subsidiary Bearskin Airlines), Kivalliq Air, Calm Air, Custom Helicopters, R1 Airlines and others.

During 2018, ultra-low cost carriers (ULCC) Swoop, a wholly-owned subsidiary of WestJet, started operating while Flair Airlines, Canada’s first ULCC, expanded its services. As well, aspiring ULCC Canada Jetlines moved closer to launch, having fulfilled prerequisites for its Canadian Aviation Document. On December 20, 2018, charter carrier Enerjet announced it would re-launch in 2019 as a ULCC with backing from three Canadian institutional investors and U.S.-based Indigo Partners, which has extensive experience in low-cost carriers.Footnote 5

International air services developments

In 2018, foreign operators offered 13.7 million scheduled seats from Canada on an average of 292 flights per day. This is up from the 13.1 million seats offered in 2017.

In 2018, Transport Canada continued its efforts to work with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and fellow member states, Canada’s aviation industry and other international organizations to promote global aviation safety and security and improve connectivity. This collaborative approach encourages economic growth while leveraging all stakeholders’ capabilities and resources.

Throughout 2018, Canada continued to build on air transport agreements with its bilateral partners, and also sought ways to build new connections and agreements. As of December 2018, Canada had air transport agreements or arrangements with over 105 bilateral partners. In 2018 Canada concluded expanded agreements with several markets, including Algeria, Egypt, Ivory Coast, Jordan, Qatar, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, the United Kingdom and the United Arab Emirates. Canada also concluded a first-time codeshare agreement with Mongolia.Footnote 6

In 2018, Canada expanded technical arrangements in several markets, including with China, Brazil, the European Union, the U.S., Australia and New Zealand. Technical assistance missions to Haiti, Lima, Peru and Israel were also launched. In 2019, these new initiatives will continue to provide support and expertise in the area of Safety Management Systems (SMSs) for aerodromes and airport inspections.

Transport Canada welcomed engagement with the United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority in 2018. Both authorities worked to minimize disruptions during the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union, commonly referred to as “Brexit”. In anticipation of the withdrawal date, Transport Canada and the United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority developed new arrangements to safeguard stable conditions in civil aviation during the Brexit transition.

Safe and secure transportation

Transport Canada processes approximately 120,000 Civil Aviation services per year. From 2017 to 2018, the department delivered:

- 30,205 pilot or flight engineer licensing services

- 962 air operator certificates

- 7,898 aircraft registration requests

- 77 air traffic controller licensing requests

- 52,247 medical assessments

- 4,463 unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) Special Flight Operating Certificates

- thousands of inspections

The department also issued 124 Canadian aviation documents to new Air Cargo Secure Supply Chain participants.

Pre-clearance

In 2018, U.S. Customs and Border Protection precleared around 15 million U.S.-bound passengers at Canada’s eight preclearance airports, under the bilateral Agreement on Air Transport Preclearance. The enabling legislation, the Preclearance Act, received Royal Assent on December 12, 2017. This brought Canada and the U.S. closer to implementing a new comprehensive preclearance agreement, which was signed in 2015. Once it comes into force, it will replace the existing air preclearance agreement and expand preclearance to the surface, rail and marine modes, and to new locations in the air mode.

Expanding preclearance will facilitate faster travel between Canada and the U.S., provide access to more destinations in both countries, bolster trade, better protect our rights and increase border security.

Child restraint system

In 2018, the Government of Canada examined Canada’s regulations for child restraint systems. This resulted in new guidance for Canadian air operators. To facilitate travel on both foreign and domestic flights, certain foreign design standards are now permitted in Canada.

This new guidance aims to improve the safety of children onboard aircraft, both at home and abroad.

A public information campaign launched in August 2018, Taking children on a plane, explained the new guidance.

General Aviation Safety Campaign

Another important goal for Transport Canada in 2018 was to decrease the number of fatal general aviation accidents through the General Aviation Safety Campaign. Launched in 2017 in collaboration with the Canadian Owners and Pilots Association (COPA), this three-year education campaign aims to improve safety through discussions and national safety seminars on subjects such as pilot decision-making, pilot proficiency and best practices in general aviation.

The campaign includes a presence on Transport Canada’s website, developed in concert with the General Aviation community, industry safety partners and aviation experts.

There are plans to continue expanding this safety program into 2019.

Other initiatives

In 2018, Transport Canada Civil Aviation adopted a lean and flexible approach to oversight, as part of the department’s transformation initiatives. Implemented in April 2018, Surveillance 2.0 and Targeted Inspections are tools based on recommendations made by the Auditor General. They balance performance-based and compliance-based oversight that meets ICAO standards. The oversight program continues to improve to keep pace with industry growth.

The State Safety Program is another initiative Transport Canada set in motion in 2018. Following guidelines from the ICAO’s Annex 19, a team of experts and specialists at Transport Canada worked to ensure our programs align with international standards.

On December 12, 2018, following extensive consultations, the Government of Canada introduced changes to Canada’s flight crew fatigue management regulations in order to make Canada’s aviation sector safer. The changes established new prescribed flight and duty limits, and rest periods that are grounded in modern science and better manage the length of time a crew member can be on the job. These changes also introduced Fatigue Risk Management Systems, which will allow operators the flexibility to vary from prescribed limits if they can show this will not affect alertness and safety.

Outlook, trends and future issues

Looking ahead, Canada plans to collaborate with other aviation authorities and safety partners to leverage their expertise, exchange best practices, and stay in pace with innovations and technology. Strengthening domestic and international partnerships to minimize technical barriers to trade will also be a benefit.

The number one cause of fatal aviation accidents in general aviation in Canada is loss of control (in-flight), or LOC-I. Transport Canada will explore innovative non-regulatory approaches to mitigate this high safety risk, such as leveraging the General Aviation Safety Campaign.

Anticipating future advances, Transport Canada is also contributing to the whole-of-government approach to developing policy for commercial space launches.

Green and innovative transportation

The aviation sector has been addressing greenhouse gas emissions through voluntary agreements with the Government of Canada since 2005. The latest agreement, signed in 2012, is Canada’s Action Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Aviation. This plan focuses on aviation fuel efficiency and identifies a series of measures to address greenhouse gas emissions. As a result of actions taken by parties under the plan, Canadian air carriers improved their fuel efficiency 15.6% between 2008 and 2017.Footnote 7

In 2016, the ICAO agreed on a new carbon dioxide standard for airplanes, the CO2 Standard. The new standard will take effect in 2020 for newly designed airplanes and in 2023 for in-production airplanes. The standard addresses emissions at the source. It is projected to cut emissions globally by 650 million tonnes from 2020 to 2040.

In 2016, the ICAO also agreed to implement a global market-based measure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from international civil aviation, the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). Under CORSIA, airplane operators with emissions over 10,000 tonnes from international flights will be required to purchase acceptable emission units, primarily from other sectors, to offset the growth of emissions in international aviation from 2020.

Regulations amending the Canadian Aviation Regulations (Greenhouse gas emissions from International Aviation – CORSIA) requiring the monitoring, reporting and verifying of emissions came into force as of January 1, 2019. The offsetting requirements of CORSIA will start in 2021.

In 2018, the ICAO finished developing a new non-volatile particulate matter standard for aircraft engines. The new standard addresses emissions at source. It will come into effect in 2023.

Chapter 4 Marine transportation sector

Map: Marine transportation network

Image description: Marine transportation network

The map of Canada shows the approximate location of the 18 CPA. Each is represented by an anchor in a blue circle. The CPA ports are (in alphabetical order): Belledune, Halifax, Hamilton, Montréal, Nanaimo, Oshawa, Port Alberni, Prince-Rupert, Québec, Saguenay, Saint John, Sept-Îles, St. John's, Thunder Bay, Toronto, Trois-Rivières, Vancouver Fraser and Windsor. Four of these ports are located in the Atlantic Provinces, five in Québec, five in Ontario and four in British Columbia.

Highlights

- The Government of Canada continues to deliver initiatives under the national Oceans Protection Plan to keep Canadian waters and coasts safe and clean for today’s use and for future generations.

- In the Great Lakes St.-Lawrence Seaway system, progress continued to reduce sulphur emissions from domestic vessels.

- A number of 2018 investments in port infrastructure through the National Trade Corridors Fund will contribute to increased trade overseas.

- The Government of Canada introduced and implemented actions under the $167.4 million Whales Initiative to protect and support the recovery of Canada’s endangered, iconic whale populations such as the Southern Resident killer whale, the North Atlantic right whale, and the St-Lawrence Estuary beluga.

Industry infrastructure

The Canadian port system

Ports and harbours are key connections supporting domestic and international economic activity. As of December 2018, Canada had 557 port facilities, 883 fishing harbours and 127 recreational harbours.

Transport Canada has a mandate for two categories of ports: 18 ports independently managed by Canada Port Authorities, shown on Map 6 in Annex A, and 44 port facilities currently owned and operated by Transport Canada.

Investments in new and existing port infrastructure have helped Canada Port Authorities diversify their services and open up access to new global markets.

In 2018, the Minister of Transport announced funding of more than $270 million under the National Trade Corridors Fund for 16 projects at eight Canadian ports. These projects will help efficiently move commercial goods to market and people to their destinations, stimulate economic growth, create quality middle-class jobs, and ensure Canada’s transportation networks stay competitive and efficient.

On November 16, 2018, the St. John’s Port Authority officially opened the newly constructed Pier 17. This $12.8 million facility will expand berthing capacity and operational capabilities in the Port of St. John’s. The Government of Canada and St. John’s Port Authority each committed up to $6.4 million in support of the expansion, to better serve people using the port and meet future industry needs.

The Port of Vancouver Authority started construction on the Deltaport truck staging facility in 2017, expected to be completed in 2020. The project will improve road safety, reduce port-destined truck queues and result in less engine idling and traffic congestion around the Deltaport marine terminal.

In spring 2018, the Minister of Transport launched a review of Canada Port Authorities with a view to optimize their current and future role in the transportation system as assets that support inclusive growth and trade.

St. Lawrence seaway system

In 2017, the agreement between the St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation and Transport Canada to manage, maintain and operate the St. Lawrence Seaway was extended to March 31, 2023. It was also announced that Transport Canada would conduct a review to examine further opportunities to ensure the Seaway continues to be positioned as a critical transportation corridor for North America.

See the Canada’s transportation network section of this report to learn more about the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway system.

Industry structure

International

According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 90% of the world’s trade travels by sea. This represented 10.7 billion tonnes of goods moved in 2018. According to the UNCTAD’s review on maritime transport in 2018, the world’s seaborne trade volumes saw a 4% annual growth, the fastest growth in five years. Growth in seaborne trade is forecasted to grow 3.8% between 2018 and 2023.

To further promote efficiency of the trade supply chain, important changes to the marine transportation sector came into force in 2018 as part of the Transportation Modernization Act.

Specifically, amendments were made to the Coasting Trade Act to allow any vessel owner to reposition their owned or leased empty containers (on a non-revenue basis) between locations in Canada. These changes will help address the current shortage of containers available for export, while increasing logistical flexibility for vessel owners and operators.

Amendments to the Canada Marine Act are also now in force, which enable Canada Port Authorities to apply for loans and loan guarantees from the new Canada Infrastructure Bank. This is expected to give Canada Port Authorities more options for financing infrastructure development that supports Canadian trade.

Domestic

Canadian registered vessels are active in domestic commercial activities, carrying on average 98% of domestic tonnage, as well as in trade between Canada and the U.S. In contrast, Canadian shippers mostly rely on foreign registered fleets to carry goods to non-U.S. international destinations.

The domestic marine sector’s main activity is transporting bulk cargo. This sector is also critical for northern resupply and offshore resource development. There are also a number of short duration and coastal passenger services across Canada.

Ferries in Canada provide an important resupply and transportation link, and play a vital role for coastal and island communities, as well as those separated by river or lake crossings where crossings have no land-based alternative. As of January 2019, the members of the Canadian Ferry Association, which includes all major ferry routes in Canada, carried more than 53 million passengers and more than 21 million vehicles in 2018.

Canadian commercial fleet

In 2018, Canada’s commercial registered fleet (1,000 gross tonnage and over) had 113 vessels, with a total of 2.7 million gross tonnes.Footnote 8 Dry bulk carriers were the fleet’s backbone, with 29% of total gross tonnage and 43% of vessels, followed by general cargo and tanker vessels.

There was also a large active fleet of 484 tugs and 1,876 barges (15 gross tonnage and over) operating in Canada, mainly on the Pacific coast (offshore).

Safe and secure transportation

The Government of Canada continues to deliver initiatives under the national Oceans Protection Plan to protect Canada’s coasts for future generations while growing the economy. In partnership with Indigenous and coastal communities, this initiative is developing a world-leading marine safety system to meet Canada’s unique needs, and enhance our ability to prevent and improve response to marine pollution incidents, from coast to coast to coast.

As a core member of the Marine Security Operations Centres, Transport Canada continues to partner with other federal government departments and agencies to leverage our combined capacity and authority to enhance Canada’s marine security.

Green and innovative transportation

Since January 1, 2015, vessels in Canadian waters and within the North American Emission Control Area must use fuel with a maximum sulphur content of 0.1%, or technology that results in equivalent sulphur emissions, to reduce air pollutants (for example, exhaust gas cleaning systems). In the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway system, progress continued under the Fleet Averaging Regulatory Regime to reduce sulphur emissions from domestic vessels. The government expects these measures to reduce sulphur oxide emissions from vessels by up to 96% by 2020.

A world-leading marine safety system requires strong environmental protection for Canada’s coastal habitants, ecosystems and marine species, including whales. Through the Whales Initiative, Transport Canada is supporting the Government of Canada’s efforts to protect and recover Canada’s endangered whales. The department is addressing the impact of day-to-day vessel traffic on endangered whales, including from the effects of underwater vessel noise and vessel strikes.

In December 2018, amendments to the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 received Royal Assent. These amendments will improve marine safety and environmental protection by strengthening government authority to regulate marine vessels and navigation. This will help protect the marine environment, including endangered whale populations. Ongoing work with other government departments, industry, non-governmental organizations, academia and Indigenous groups is key to the continued success of measures under the Whales Initiative.

Additional measures to protect Southern Resident killer whales were announced in October 2018, including:

- working with the marine industry on voluntary measures to reduce underwater noise

- expanding real-time monitoring systems to detect and avoid whales

- developing underwater noise management plans to reduce noise created by Canadian fleets

Recent collaborative actions to reduce underwater noise include:

- Implementing a voluntary vessel slowdown and lateral displacement trial in the Salish Sea in summer 2018, to assess and reduce underwater noise from vessel traffic

- Establishing a Southern Resident Killer Whale Indigenous and Multi-stakeholder Advisory Group to coordinate activities to recover these whales, as well as two technical working groups on vessel noise

- Advancing international action on vessel noise, and in particular to promote quiet ship design standards and technologies

- Signing one and negotiating two other conservation agreements with key industry stakeholders, to formalize voluntary measures and commit to more mitigation measures on vessel noise

- Distributing a discussion document to industry stakeholders on underwater noise management plans, custom plans developed by operators to reduce their fleets’ underwater noise

For a second year, Transport Canada implemented speed management measures in the Gulf of St. Lawrence between April 28 and November 9, 2018, minimizing risks to navigational safety and North Atlantic right whales. After consulting with the marine industry on 2017 measures, the department put a speed restriction in place for vessels 20 m or longer travelling through much of the western Gulf of St. Lawrence. To minimize impact on the marine industry, vessels were allowed to travel at safe operational speeds in parts of two shipping lanes when no whales were observed.

Transport Canada’s National Aerial Surveillance Program flew a total of 325 flight hours in 2018 to monitor the slowdown measures. With 4,612 transits through the speed reduction zone, only three penalties were issued, and an additional six cases were pending final review at the end of 2018.

Most importantly, there were no known North Atlantic right whale deaths in Canadian waters in 2018.

Oceans Protection Plan

As part of the OPP, the Government has announced initiatives worth more than $1.5 billion, including:

Meaningful partnership-building

Transport Canada continued to engage and partner with Indigenous peoples, coastal communities, marine stakeholders, and provinces and territories through over 350 engagement sessions held so far. The Government of Canada signed a historic Reconciliation Framework Agreement with 14 Pacific North and Central Coast First Nations in British Columbia to work together to protect and manage the province’s Pacific Coast.

Northern low-impact shipping corridors

In fall 2018, Transport Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard and the Canadian Hydrographic Service initiated a first round of engagement sessions in Canada’s Arctic with Indigenous organizations, territorial and provincial governments to discuss the development of a governance framework and priority geographic locations for services along the Corridors. Industry, academia and other non-governmental organizations will be engaged in 2019. Discussions with partners and stakeholders are expected to be ongoing over the next few years.

Pilotage Act Review

Under the Oceans Protection Plan, the Government of Canada launched the Pilotage Act Review in 2017, to modernize the legislative and regulatory framework for pilotage services. Informed by extensive analysis and consultation with stakeholders and Indigenous peoples, the Review’s final report was publicly released on May 22, 2018 and included 38 recommendations. Following further analysis and consultation, the federal government introduced amendments to the Pilotage Act in April 2019 that will modernize the legislation and enhance the safety, efficiency, and transparency of Canada’s marine pilotage system.

Anchorages Initiative and Interim Protocol

This national initiative continues to examine the management of anchorages outside of public ports including the environmental, economic, social, safety and security impacts of anchorages and best practices for ships at anchor. In February 2018, Transport Canada implemented the Interim Protocol for the use of Southern British Columbia Anchorages which includes temporary and voluntary procedures to balance the use of anchorage locations outside of ports and mitigate the impact of ships when at anchor.

Bill C-48: Oil Tanker Moratorium Act

The bill proposes to formalize an oil tanker moratorium on British Columbia’s north coast, which could compliment the current voluntary Tanker Exclusion Zone. The proposed oil tanker moratorium will extend from the Canada/U.S. border in the north, down to the point on B.C’s mainland adjacent to the northern tip of Vancouver Island, including Haida Gwaii. Oil tankers carrying more than 12,500 metric tons of crude oil or persistent oil as cargo will be prohibited from mooring/anchoring or loading or unloading any of those oils at a port or marine installation in the moratorium area. The Bill passed Second Reading in the Senate on December 11, 2018, and is currently under study in the Senate Standing Committee on Transport and Communications.

Stronger “polluter-pays” principle

Transport Canada Amended the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 and the Marine Liability Act, which received Royal Assent in December 2018. This will strengthen marine environmental protection, enhance marine safety, and modernized the Ship-Source Oil Pollution Fund, namely to provide unlimited compensation to pay all eligible claims from a ship-source oil spill and provide quicker access to compensation.

Cumulative Effects of Marine Shipping Initiative

This initiative is being rolled out and tested in six pilot sites across Canada. Transport Canada is relying on regional engagement and collaboration with Indigenous nations, industry and other stakeholders in each of the six identified pilot sites. Through the first year of engagement much information has been gathered, including marine vessel activities and resulting stressors of concern. This initiative is collaborative, and as such the approach to developing a framework for cumulative effects and testing methodology will create meaningful relationships.

Engaging Canadians

Transport Canada consulted with Canadians on Oceans Protection Plan initiatives through the Let’s Talk OPP Portal.

Marine Training Program

Transport Canada expanded marine training programs in the North through a signed contribution agreement with the Nunavut Fisheries and Marine Training Consortium. The department also worked with Indigenous communities on the West Coast to deliver training on marine search and rescue and environmental response.

Enhanced maritime situational awareness

Transport Canada awarded contracts to develop an initial solution for a maritime awareness information system. Funding has also been awarded to pilot hosts across Canada to support their participation in a pilot project.

The department partnered with 10 coastal communities on pilot projects at nine sites. The aim was to create a new user-friendly maritime awareness information system, which will increase access to local maritime information for local communities.

Vessels of concern

Transport Canada implemented a national strategy on abandoned and wrecked vessels. This comprehensive strategy includes several measures to mitigate the impacts and risks posed by abandoned, hazardous and wrecked vessels. Measures include:

- Putting in place two short-term funding programs to help communities assess and remove existing highpriority abandoned vessels

- Developing a national inventory to catalogue abandoned and wrecked vessels, which also includes a risk assessment methodology for prioritizing future actions on high risk

- Enhancing vessel owner identification system

- Creating an owner-financed long-term fund that will help remove abandoned and wrecked vessels from Canadian waters

The Wrecked, Abandoned and Hazardous Vessels Act aims to protect coastal and shoreline communities, the environment and infrastructure by bringing into Canadian law the Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks, 2007, and by holding owners responsible for their vessel throughout its life-cycle, including its disposal. Since the launch of the Abandoned Boats Program, funding has been announced to remove and dispose 44 vessels, conduct 87 removal assessments and support education, awareness and research projects.

Chapter 5 Rail transportation sector

Map: Rail transportation network

Image description: Rail transportation network

The map of Canada shows the layout and extent of the Canadian rail system. This system currently has over 45,000 route-kilometres of track broken down into Canadian National track (52.2 per cent of the system, represented by blue lines), Canadian Pacific track (30.8 per cent, represented by red lines) and other railways track (17.0 per cent, represented by orange lines).

Highlights

- The new Transportation Modernization Act supports a transparent, fair, efficient and safe Canadian rail system, one which meets long-term needs, and facilitates trade and economic growth.

- The Statutory Review of the Railway Safety Act tabled in Parliament in April 2018 concluded the act is sound and Canada’s rail transportation system is getting safer, but there are persistent issues that need to be addressed.

- Transportation by rail contributes to the efficiency of Canada’s transportation network by reducing congestion and wear-and-tear on roads and highways.

- Following adoption of the Transportation Modernization Act, Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway published their first annual Grain Reports, which assess their abilities to move Western grain during the crop year.

Industry infrastructure

The rail system is a critical part of Canada’s trade and transportation corridors. The Canadian rail system currently has 41,465 route-kilometres of track, as illustrated on Map 7 in Annex A. Of these:

- Canadian National (CN) owns 52.8% (21,879 km)

- Canadian Pacific (CP) owns 30.7% (12,709 km)

- other railways own 16.6% (6,812 km)

Industry structure

Freight sector

The freight rail transportation sector specializes in moving heavy, bulk commodities and containerized traffic over long distances. In 2018, the rail transportation system moved more than 331.7 million tonnes of freight. The main categories of freight were:

- coal (14%)

- containerized cargo (14%)

- grain (13%)

- forest products (9%)

- chemicals (8%)

- petroleum products (excluding crude oil, 8%)

- potash (7%)

Canada has two major Class I freight railways, CN and CP, which are responsible for most freight rail traffic. Large U.S.-based carriers also operate in Canada. Examples include the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railway Company and CSX Transportation Inc. Together, CN, CP and BNSF provide strategic links in the trade route between Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. BNSF’s service to Canada’s Pacific Gateway gives Vancouver the unique advantage of being the only port on the North American West Coast served by three Class I railroads.

In terms of equipment, Class I railway carriers had 2,280 locomotives in 2017, with 47,759 freight cars, mainly hopper cars, boxcars, flatcars and gondolas, and 480 passenger cars.

There are 70 companies that fall under the authority of the Railway Safety Act. Twenty-six of these companies are federal railway companies, who must also hold a Certificate of Fitness from the Canadian Transportation Agency. Additionally, there are multiple provincially regulated short line railways that typically connect shippers of products with Class I railways or to other short lines and ports in order to move products across longer distances. Short-line railways transport $20.3 billion worth of freight to and from continental rail networks, such as CN and CP, and to ports and terminals.

In addition to short lines focused on moving freight, other short lines provide passenger rail services, such as the Rocky Mountaineer Railway.

Passenger sector

The passenger rail sector provides commuter, intercity and tourist transportation services. In 2018, intercity passenger railways transported 4.8 million people, up 8.2% from 2017 and up 28.0% from the previous five-year average.

VIA Rail, a Crown corporation established in 1977, operates Canada’s national passenger rail service on behalf of the Government of Canada. VIA Rail operates mainly over shared infrastructure owned by freight rail companies.