Table of Contents

- Glossary – Key aviation wildlife-management terms

- A policy of protection – New knowledge of airport-vicinity hazards

- Building an effective response – Reducing aviation risks

- Something for everyone – Who can use ABRAPs

- Safer skies, step by step – Putting ABRAPs to work

- For airport operators

- For municipal authorities

- For land-use owners and operators

- Minimizing hazards – Risk-mitigation measures

- An eye on the big picture – Integrating wildlife-management activities

- Resources

- Documents and links

- Contacts

Glossary

Like many specialized fields, aviation wildlife management has a language all its own. Here are definitions for key terms used throughout this document.

KEY AVIATION WILDLIFE-MANAGEMENT TERMS

ABRAP (Airport Bird-hazard Risk Analysis Process)

A step-by-step procedure developed by Transport Canada to help airport and municipal authorities, airport-area landowners, developers and operators identify and counter off-airport wildlife hazards that have the potential to pose risks to aviation safety.

Airport vicinity

For purposes of wildlife control, an airport’s vicinity comprises all surrounding lands that fall within bird-hazard risk zones described in this document. Since all airports are different, the size and shape of each airport’s vicinity is unique.

AWMP (AirportWildlife-management Plans)

Under Transport Canada regulations, airport authorities are responsible for managing all on-airport wildlife. To carry out this responsibility, airports develop and implement performance- based AWMPs to identify existing wildlife hazards, undertake appropriate mitigation measures, measure results of all interventions, and review and update the plans.

Hazardous wildlife

Species of birds and mammals that are most likely to cause damage when struck by aircraft. Hazardous species also include those that attract other wildlife to airport environments.

IFR (Instrument flight rules)

Rules that apply when flying an aircraft by means of reference to cockpit instruments.

Mitigation

Activities undertaken to reduce risks posed by wildlife in airport environments and air-traffic zones. Wildlife-management mitigation measures include a variety of passive and active techniques, from habitat modification to scaring and lethal control.

Performance-based measurement

In government and industry, most modern programs and initiatives undergo ongoing re v i ews to prove their value to taxpayers and shareholders. Effectiveness is determined by performance, which is measured through a variety of built-in mechanisms: data collection, monitoring, re p o rting, etc. Resulting measurements provide the information needed to make adjustments to a program and enhance its performance.

System Safety

Safety is a major concern of all organizations. System safety recognizes that protection is best ensured when all elements of an organization are integrated and co-ordinated. The system might include different departments within a company. In the case of airport wildlife management, the system of government who have roles to play in ensuring safety in areas on and around Canada’s airports. This system can achieve the highest levels of safety when these stakeholders communicate and work together to minimize risks.

VFR (Visual flight rules)

Rules that apply when flying an aircraft by means of visual reference to the ground.

Wildlife strike

A collision between an aircraft and wildlife. Birds are the species most often involved in strikes, but mammals such as deer and coyotes are also hazards.

A policy of protection

NEW KNOWLEDGE OF AIRPORT-VICINITY HAZARDS

In its many civil-aviation responsibilities, Transport Canada remains focused sharply on the safety of air travellers. This focus has led the department to examine numerous potential hazards, including those found on and in areas around Canadian airport s.

Working with industry experts, and the benefit of extensive international scientific research, Transport Canada has confirmed that these hazards include many forms of wildlife, from birds and deer-which are often struck by aircraft-to smaller prey animals that attract m o re hazardous species.

Research also indicates conclusively that wildlife are attracted to, and sustained by, a wide range of activities that offer food sources and safe habitats on lands adjacent to airports. These land-use activities include:

- certain agricultural practices,

- fishing and fish-processing operations,

- food-service operations,

- sewage treatment facilities,

- quarry operations,

- sports and recreation facilities,

- water management operations,

- waste disposal and recycling facilities,

- wetlands, and

- wildlife refuges.

A dynamic challenge

Wildlife respect no boundaries, physical or regulatory, and often congregate in and pass through air-traffic corridors, such as take-off, departure, approach and landing areas. The result is risks to aircraft and air travelers-risks that can be minimized when airport-area stakeholders work together and systematically integrate their efforts to:

- identify wildlife hazards and risks;

- plan, coordinate and implement management and mitigation measures; and

- measure results.

These system-safety activities can help airports and nearby facilities become less attractive to wildlife, and prevent many airport-vicinity lands from being used or developed in manners that are incompatible with the safe operation of aircraft.

New factors in wildlife management

This airport-vicinity focus is not new for Transport Canada. Since the late 1980s, the departmental publication TP 1247, Guidelines for Land Use in the Vicinity of Airports, proved a useful and effective tool primarily for zoning. However, in an era where airports are managed by private sector authorities, this method of pre scribing national airport standards lacks both effectiveness and flexibility in respecting and accommodating the varied , site-specific scenarios that exist at each airport.

What’s more, many new factors demonstrate the need to adopt a risk-based approach that applies the latest scientific knowledge in managing land uses near airports.

Recent work1 by various industry experts, for example, has re vealed new evidence of numerous, complex and often inter-dependent factors that contribute to the challenge of managing potentially hazardous off-airport land-use activities:

Increasing size of hazardous bird populations

The No rth American Canada Goose population, for example, is estimated to have tripled from two million to six million during the 10-year period between 1990 and 1999.2

Increasing number of aircraft operations

Canadian air traffic continues to increase, influenced only occasionally by such short-term anomalies as the temporary downswing experienced after the events of September 11, 2001.

Disparate stakeholders

Concerned airport - area groups and individuals include:

- airport owners and operators,

- pilots,

- airlines,

- airline passengers,

- aircraft manufacturers,

- property owners and developers ,

- land-use planners and operators, and

- municipal, provincial, territorial and federal government authorities.

While these stakeholders share a common concern for public safety, their respective goals are often unaligned.

Potential shortcomings in aircraft design

Many current aircraft components, systems and engines are not certified to withstand the impact force of even one large flocking bird.3

Increasing numbers and varieties of airport-vicinity land uses

In recent decades, research has helped to significantly expand the list of potentially hazardous airport-vicinity land uses.

Urban and suburban development

Residential, commercial and industrial growth has encroached on many Canadian airports that were originally located in relatively remote rural settings. This development has multiplied the numbers and types of land uses- and possibly the range of wildlife attractants-in areas immediately adjacent to airports.

Vulnerability of aircraft in proximity to airports

According to a leading expert,4 "73% of all [bird] strikes and 67% of strikes causing substantial damage occur at ≤ 500 feet above ground." It is at these altitudes, and over areas tens of kilometres beyond airport boundaries, that aircraft are most vulnerable to loss of control.

1 These works include Bird Use, Bird Hazard Risk Assessment, and Design of Appropriate Bird Hazard Zoning Criteria for Lands Surrounding the Pickering Airport (LGL Limited report no. TA2640-2, May 2002), and System Safety Review of Land Use in the Vicinity of Vancouver International Airport. See Resources for elect ronic versions of both documents.

2 Waterfowl Population Status Report. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, 2001.

3 Kelly, Terry; Sowden, Captain Richard. Safety-risk Assessment of Canada Geese in the Greater To ronto Are a. Ottawa. Transport Canada. 2004. See Resourc e s.

4 Dolbeer, Dr. Richard A. Height Distribution of Birds as Recorded by Collisions with Civil Aircraft. Sandusky, Ohio. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2004 Auk (in review). See Resources.

Damage to a Van's Aircraft RV-6, which struck a bird at 140 knots, 2,500 feet above ground, and in total darkness.

The bird apparently struck the top half of the windscreen and disintegrated on the rollbar. The pilot was temporarily blinded by bird remains, but managed to clear his vision and land safely. Note that such cabin breaches affect aircraft response considerably. The hole in this aircraft's windscreen, for example, increased drag and the aircraft's sink rate.

Bird-strike damage to a Snowbirds CT-114 Tutor (Canadian Forces 431 Air Demonstration Squadron)

Multiple jurisdictions

While airport operators are empowe red to manage potentially hazardous land-use activities on airport property, zoning of off-airport lands is generally a municipal responsibility. Regulation of land-use activities often falls to provincial authorities, while overarching responsibility for aviation safety and security lies with the federal gove rnment.5 This intricate jurisdictional environment can challenge the goals of system safety, often highlighting conflicting requirements of individual stakeholders rather than enabling cooperation to identify and address common issues.

Questions of accountability

Perhaps the most compelling reason for stakeholders to adopt a co-operative approach is liability. As part of its broad examination of off-airport land uses, Transport Canada conducted an extensive study 6 of related liability issues.

The study found that various parties could be implicated in an aircraft accident involving a bird strike, including the owner/operator of a land-use facility adjacent to airport lands, an airport operator, the aircraft operator, air navigation service providers, the aircraft manufacturer and government regulators.

5 While the Minister of Transport continues to have authority under the Aeronautics Act to operate airports and provide aviation services, the Minister's role over the last several years has evolved to one almost exclusively limited to regulating aviation safety and security. The operation of most airports has been transferred to local authorities and the provision of air traffic control and other air traffic, navigation, weather and information services has been assumed by NAV CANADA.

6 Mazowita, Grant. Liability Issues Associated with Waste Disposal Facilities and other Land Uses as they may affect Aviation Safety by virtue of Attracting Birds. Ottawa. LGL Limited for Transport Canada. 2004. See Resources.

Building an effective response

REDUCING AVIATION RISKS

Given the most recent research concerning aviation wildlife hazards, the challenge is to develop a scientifically sound mechanism that enables the effective management of potentially hazardous off-airport land uses. This management tool must align with Transport Canada's policy to establish a performance-based regulatory program in which aviation stakeholders-including airport operators, air-navigation service providers, airlines, aircraft manufacturers and maintenance facilities-undertake and demonstrate proactive safety-management practices.

Consistent with this program, and according to specific sections of Canadian Aviation Regulation 302, Division III, Wildlife Planning and Management, airport operators are required to develop and implement airport wildlife management plans (AWMPs). These plans enable the systematic identification and mitigation of wildlife hazards that are unique to each airport. Once implemented, AWMPs become formally documented strategies that are customize d to reduce wildlife-related safety risks. The entire planning process is performance-based to ensure that mitigation is actively and regularly monitored, measured and updated.

AWMPs have proven highly effective in Canada and a round the world in countering airport wildlife hazards- especially birds. Howe ver, evidence has re vealed that while most bird strikes occur on or over airports, the birds invo l ved in these incidents usually originate elsewhere. Many wildlife strikes occur as birds and mammals move from one off-airport pro p e rty to another.

Matching ecosystem with air-safety system

With this new evidence in mind, Transport Canada developed the airport bird-hazard risk analysis process (ABRAP). This comprehensive and flexible tool is an extension of airport wildlife-management planning designed specifically to help identify and mitigate wildlife hazards associated with off-airport land uses.

ABRAP respects the current regulatory environment, not only enabling Transport Canada to intervene at the systems, rather than operational, level-but also ensuring responsibility for safety in the industry resides with accountable executives.

ABRAP is also an effective way to inform and engage off-airport stakeholders. In fact, the process offers the gre a test benefit when conducted with the meaningful and coll aborative participation of land-use owners and developers , and municipal planners. These stakeholders play import a n t roles in reducing wildlife risks to aircraft; they determine in large measure the success that airport operators can achieve in meeting the regulated re q u i rement to mitigate aviation wildlife hazards.

A helpful overview

Safety Above All presents an overview of the airport birdhazard analysis process, introducing a mechanism that can help airport and municipal authorities survey and categorize off-airport land uses in terms of their potential to attract high-risk wildlife species. Findings can then be employed to mitigate risks-through airport- and municipal- zoning regulations, for example-and improve operational safety.

Something for everyone

WHO CAN USE ABRAPS

The airport bird-hazard risk analysis process is intended for use by everyone who could become directly or indirectly involved with the identification, management or evaluation of wildlife hazards on or near airports. Those who can benefit include:

- airport operators,

- municipal politicians and planners,

- airport-area land and business owners,

- property developers,

- parks and recreation staff,

- conservation groups,

- various provincial ministries,

- Environment Canada, and

- Transport Canada.

These stakeholders might use ABRAPs and their findings in a number of different circumstances, including:

- Development of airport wildlife management plans by airport authorities;

- Awareness-building public forums on aviation wildlife management;

- Familiarizing pilots with potentially hazardous land-use locations near airports ;

- Determining requirements for bird - hazard and aeronautical zoning regulations during the design phase of new airports;

- Planning-phase evaluations of expansions or modifications to existing airport runways or flight paths;

- Municipal evaluations of plans for development of, or changes to, potentially hazardous land-uses in the vicinity of airports ;

- Influencing planning policies concerning future development of off-airport lands; and

- Evaluations by Transport Canada and other regulatory bodies of the appropriateness and effectiveness of wildlife control measures taken on and near airports.

ABRAPs are most often used by airport operators to develop long-term plans to coordinate the management of lands on and around airports. Airport managers might use the tool to identify off-airport land-uses that attract highrisk wildlife species. With this knowledge, airport managers can enter into agreements with property owners to manage risks associated with potentially hazardous properties.

Municipal planners could use ABRAP findings and contribute to air safety by updating and improving the effectiveness of zoning bylaws, and by applying these new regulations to areas beyond airport boundaries.

By consulting ABRAP findings, property developers could minimize risks associated with wildlife by focusing only on land-use options that comply with aeronautical and municipal zoning.

Transport Canada can use ABRAP as an audit framework to help forecast the degree to which AWMPs will reduce wildlife-related safety risks. The department’s inspectors could also rely on ABRAPs when conducting or evaluating risk assessments of airport operations.

Safer skies, step by step

PUTTING ABRAPS TO WORK

ABRAP is a tool that integrates aircraft flight patterns, potentially hazardous bird species, and related land uses. Initial actions are carried out by airport operators, who:

STEP 1: Identify resident and itinerant aircraft types and map their flight paths during vulnerable low-altitude phases, including take-offs, approaches missed approaches and landings.

STEP 2: Analyze area bird populations (in terms of bird size, flight paths and flocking behaviour) to determine their potential threat to aircraft safety.

STEP 3: Examine land uses surrounding airports to determine whether they are likely to attract hazardous bird species.

By integrating these data, bird hazards and aircraft safety risks associated with individual airports can be determined. Findings can then be used by all stakeholders- including municipalities and land owners-to determine what measures should be taken to minimize risks.

A basic overview

The process described in this section simplifies ABRAP to help all stakeholders develop an appreciation for the safety roles they might play at nearby airports. In fact, ABRAP's complexities arise from its capacity to accommodate the variety of scenarios in which the process could be applied. After all, no two Canadian airports are alike. They differ in size, location and traffic volume. They're serviced by a range of aircraft types, home to varying kinds of wildlife, and surrounded by vastly different land-use activities.

A model airport

For the purposes of this overview, Figure 1 presents a fictional, mid-sized Canadian airport. The airport is located approximately 15 km east of a river, and encroaches on three different municipalities. Lands surrounding the airp o rt are home to a variety of commercial, agricultural and conservation activities-many of which might have an impact on air safety.

For airport operators

The key first steps in the ABRAP process are to define primary, secondary and special bird hazard zones (BHZs).

PRIMARY BHZS generally enclose airspace in which aircraft are at or below altitudes of 1500 feet AGL (above ground level). These are the altitudes most populated by hazardous birds, and at which collisions with birds have the potential to result in the greatest damage.

SECONDARY BHZS are buffers that account for:

- variables in pilot behaviour and technique;

- variations in departure and arrival paths that are influenced by environmental conditions, ATC (air traffic control) requirements, IFR versus VFR flight, etc.; and

- unpredictability of bird behaviour, and variations in bird movements around specific land uses.

SPECIAL BHZS, though often distant from airports, may regularly attract potentially hazardous species across primary or secondary zones (see Step 2).

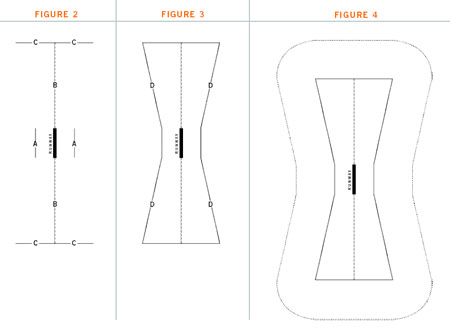

STEP 1. ESTABLISH PRIMARY AND SECONDARY BIRD HAZARD ZONES (BHZS)

- Draw lines parallel to, and 2 kms 7 on each side of, the full length of all runway centerlines. (Lines A in Figure 2.)

- Draw an extended centerline 9 km in length from the approach and departure ends of all runways. (Lines marked B in Figure 2.)

- Draw lines perpendicular to, and 4 km from each side of the ends of, extended runway centerlines. (Lines marked C in Figure 2.)

- Join the ends of lines A and C on each side of all runway centerlines to define the airport's primary bird-hazard zone. (Lines marked D in Figure 3).

- Establish the airport's secondary bird-hazard zone by creating a boundary 4 km beyond the edges of the primary BHZ. (Dotted line in Figure 4)

7 Note that the size of specific zones is dictated in part by aircraft types and the maneuvering area encompassed in circuit patterns. For the purposes of this overview, size has been set arbitrarily to accommodate FAR 25 transport-category aircraft.

STEP 2: ESTABLISH SPECIAL BIRD HAZARD ZONES

While land uses within the primary and secondary BHZs may attract and sustain hazardous wildlife, activities beyond the zones can also present hazards. The golf course and portions of the landfill east of the airport in Figure 5, for example, are outside the secondary zone. Nonetheless, daily flights of thousands of gulls move between locations on the river west of the airport- where the birds roost each night-and the landfill and golf course where they feed and loaf daily. Because these flights can take the gulls through either the primary or secondary BHZs, the landfill and golf course become special bird-hazard zones.8

8 Special bird hazard zones can be identified only after detailed studies of bird movements have been undertaken by bird-hazard experts or qualified field biologists as part of the process to create airport wildlife management plans. Such studies will indicate, for example, whether bird movements in the vicinity of an airport might be drawing birds through air-traffic corridors, or primary or secondary zones.

STEP 3. IDENTIFY RISKS RELATED TO LAND-USE ACTIVITIES WITHIN THE BIRD HAZARD ZONES

Airport operators can use the knowledge gained through the creation of BHZs to:

- Develop or modify airport zoning laws, restricting future high-risk land uses, for example.

- Provide guidance for existing land-uses, informing municipal authorities, landowners and operators of potential hazards related to area land-use activities. Airport operators may want to advise these stakeholders of the need to determine the presence of, and the degree of risk associated with, local bird species (Table 2) that could be attracted to a land-use. Stakeholders could also be informed about resources (reference materials, professionals, etc.) that are available to help mitigate risks.

TABLE 1 - HAZARDOUS LAND-USE ACCEPTABILITY BY BHZ 9

| RISK | LAND USE | LAND-USE ACCEPTABILITY BY ZONE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Special | ||

| High | Putrescible waste landfills | No | No | No |

| Food waste hog farms | No | No | No | |

| Fish processing/packing plants | No | No | No | |

| Horse racetracks | No | No | No | |

| Wildlife refuges | No | No | No | |

| Waterfowl feeding stations | No | No | No | |

| Moderate | Open or partially enclosed waste transfer stations | No | No | Yes |

| Cattle paddocks | No | No | Yes | |

| Poultry factory farms | No | No | Yes | |

| Sewage lagoons | No | No | Yes | |

| Marinas/fishing boats/fish cleaning facilities | No | No | Yes | |

| Golf courses | No | No | Yes | |

| Municipal parks | No | No | Yes | |

| Picnic areas | No | No | Yes | |

| Low | Dry waste landfills | No | Yes | Yes |

| Enclosed waste transfer facility | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Wet/dry recycling facility | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Marshes, swamps & mudflats | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Stormwater management ponds | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Plowing/cultivating/haying | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Commercial shopping mall/plazas | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Fastfood restaurants | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Outdoor restaurants | No | Yes | Yes | |

| School yards | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Community & recreation centers | No | Yes | Yes | |

| Limited | Vegetative compost facilities | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Natural habitats | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Inactive agricultural fields | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Inactive hay fields | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Rural ornamental & farm ponds | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Residential areas | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

9 Pickering Airport Site Zoning Regulations: Mitigation of Bird Hazards Arising From Particular Land Uses. LGL Limited Report No. TA2916-2. Transport Canada. 2004.

See Resources.

Land-use acceptability is site sensitive, and can be determined only through detailed assessments of each airport and its surroundings. Table 1 presents a partial list of potentially hazardous land uses in the vicinity of Pickering Airport (Ontario) according to a simple four-level ranking of risk developed for Transport Canada. The table also indicates general land-use suitability in primary, secondary and special bird hazard zones. For example, putrescible waste landfills (high risk) are discouraged in all BHZs; fastfood restaurants (low risk) are generally permissible in secondary and special zones; residential areas (no or limited risk) are permissible in all zones provided any development complies with other municipal and airport zoning conditions (such as those governing noise, obstructions, electric interference, etc.).

Although the table lists discreet categories, land-use suitability is dynamic and subject to change based on a variety of factors, including seasonal considerations and the range of activities that may be associated with a specific site. For example, agricultural fields can be classified as posing limited risk as long as they remain inactive. The moment cultivation begins, the degree of risk escalates, since the turning of soil, seeding, etc., increase the attraction to wildlife.

Risk may also escalate incrementally due to concentrations of land uses. For example, a golf course’s attractiveness to birds may increase if the facility is bordered by a stormwater management pond, marsh or agricultural operation.

Finally, it’s important to note that risks associated with many land uses can be reduced through appropriate mitigation and monitoring. The acceptability of a commercial shopping plaza in a primary BHZ, for example, would depend on the effectiveness of facility design-or the property owner’s active, calculated interventions-to minimize the operation’s attractiveness to potentially hazardous bird species. 10 ABRAP findings can be used to:

TABLE 2 - BIRD HAZARD RANKING SYSTEM 11

| LEVEL OF RISK | CHARACTERISTICS | ILLUSTRATIVE SPECIES |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 (Highest) | Very large (>1.8 kg), flocking | geese, cranes, cormorants |

| Level 2 | Very large (>1.8 kg), solitary | Bald Eagle, Turkey Vulture |

| Large (1-1.8 kg), flocking | Mallard, Great Black-backed Gull | |

| Level 3 | Large (1-1.8 kg), solitary | Red-tailed Hawk |

| Medium (300-1000 g), flocking | American Crow | |

| Level 4 | Medium (300-1000 g), solitary | Cooper’s Hawk |

| Small (50-300 g), flocking | European Starling | |

| Level 5 | Small (50-300 g), solitary | Eastern or Western Meadowlark |

| Very small (<50 g), flocking | swallows | |

| Level 6 (Lowest) | Very small (<50 g), solitary | warblers, vireos, sparrows |

10 For a discussion of mitigation options see Davis, R.A. and A.L. Lang. 2004. Pickering Airport Site Zoning Regulations: Mitigation of Bird Hazards Arising From Particular Land Uses. Report 2916-2 by LGL Limited, King City, ON for Aerodrome Safety Branch, Transport Canada, Ottawa. 29 p. See Resources.

11 Davis, Rolph; Kelly, Terry; Sowden, Captain Richard. Airport Bird Hazard Risk Analysis Process. Transport Canada. 2004. See Resources.

STEP 4. INTEGRATE FINDINGS INTO AIRPORT WILDLIFE-MANAGEMENT PLANS (AWMPs)

ABRAPs are an important part of airport wildlife-management planning. They extend operators’ views beyond airport boundaries to provide, for example, new and broader insight into the sources of airportarea wildlife hazards. By integrating ABRAP findings into the AWMP process, operators can enhance safety and vastly improve the effectiveness of these plans.

- inform the creation of AWMPs at airports that do not currently maintain these plans;

- update existing plans which, according to regulation, must be regularly reviewed; and

- demonstrate to federal and provincial regulators, municipal authorities, airport authority boards of directors, and insurance underwriters, among others, that airports are undertaking proactive and holistic measures to improve aviation safety.

Victoria International Airport, British Columbia

For municipal authorities

Municipal authorities can review For airport operators to learn more about how ABRAPs are carried out, but it is the findings of these analyses that are of most value.

Airport authorities will be pleased to make ABRAP findings available. They understand it is important to work closely with neighbouring municipalities and other local partners to address safety issues beyond the boundaries of an airport fence.

ABRAP maps of primary, secondary and special bird hazard zones may be of particular interest to municipalities. These maps illustrate areas around an airport in which aircraft are at the greatest risk of striking birds. In effect, the maps plot zones around the flight paths of aircraft that approach, depart, or cross airspace in the vicinity of, an airport.

A greater view

One thing that’s immediately clear about primary, secondary and special bird hazard zones (BHZs) is that they extend beyond airport boundaries. In fact, the zones may encroach on hundreds of different properties, including residential and agricultural areas, industrial parks and recreation facilities-many of which may be attracting and sustaining wildlife that pose hazards to air traffic.

With ABRAP maps and findings in hand, municipal authorities can:

- Familiarize themselves with existing, potentially hazardous off-airport land-use activities,

- Consider re-zoning undeveloped areas around airports,

- Review existing development plans to minimize associated hazards, and

- Determine how best to work with airport authorities and property owners to improve s afety.

For land-use owners and operators

Here are a few easy steps to help these airport-area stakeholders determine whether or not their operations might have an impact on air safety:

STEP 1. REVIEW ABRAP FINDINGS

- Contact local airport authorities to obtain a map of primary, secondary and special bird hazard zones (BHZs).

- Plot location of land use. If it falls within one of the BHZs, proceed to step 2 or 3 below. (See Table 1 for a list of potentially hazardous off-airport land uses. Note, however, that this is a partial list only, and was developed for a specific site; omitted land uses may still have the potential to pose air-safety risks. Consult with airport authorities or a bird-hazard specialist 12 to be sure.)

STEP 2. DETERMINE PERMISSIBILITY OF PROPOSED NEW LAND-USE DEVELOPMENTS, OR MODIFICATIONS TO EXISTING LAND USES

- Consult with airport authorities and municipal planners to determine whether existing or pending aeronautical and municipal zoning will permit proposed developments or modifications.

- If the land use is permitted, but has been identified as potentially hazardous, consider obtaining the services of a bird-hazard specialist. These professionals can identify the species of birds that might frequent the pro p e rt y, as well as their associated risks. If the birds are high risk (see Table 2), or are attracted regularly or seasonally to the pro p e rty in large numbers, a specialist can recommend appropriate mitigation (see Minimizing Hazards, pg. 14).

STEP 3. DETERMINE PERMISSIBILITY OF EXISTING LAND USES

Land-use owners and operators can consult with airport authorities and municipal planners to determine how ABRAP findings may affect aeronautical and municipal zoning. Existing land uses are often exempt from conditions imposed by new zoning bylaws. However, the mitigation measures required to conform to these new conditions may be relatively simple and inexpensive in terms of the local air-safety benefits they deliver.

12 Airport managers will be pleased to recommend bird-hazard experts who have appropriate wildlife-management experience.

On November 19, 1998, a British Airways B747-400 encountered a flock of Snow Geese at 1,000 feet above ground on approach to Dorval International Airport (now Montréal-Pierre Elliott Trudeau International), Montreal. Crew members estimate the aircraft struck as many as 40 birds.13 To a layperson’s eye, photographs often fail to convey the extent of aircraft damage-and seriousness of a bird-strike event. The electrics and number four engine failed, and the crew had serious concerns about the health of engines two and three. Thankfully, the crew was able to guide the aircraft to a safe landing; however, it’s important to note that no airlines currently train flight crew for incidents of this magnitude. Of equal importance, no aircraft are certified to withstand the number and severity of impacts incurred in this event.

< p>It’s difficult to determine the exact costs of such a strike. Physical damage to the aircraft likely totalled millions of dollars; the cost of a single engine fan blade (see photo on upper left) is more than CDN $15,000. Add to this the cost of removing the aircraft from service, the inconvenience (and trauma) to passengers, the scrambling of airport emergency response teams, and the rippling financial effects on airport and airline schedules.

Minimizing hazards

RISK MITIGATING MEASURES

Once airport - area land-use activities have been identified as sources of potential wildlife hazards, stakeholders can i n vestigate appropriate ways to mitigate, or reduce, associated risks.

One of the best ways to reduce wildlife risks is to build mitigation into the design of each site. This proactive approach enables developers to determine whether a facility is likely to attract and sustain potentially hazardous wildlife, and then build to minimize associated risks. In the case of a stormwater retention pond, for example, a municipality could include design features that would make the site less attractive to potentially hazardous waterf owl and gulls.

A job for the pros

Obviously, built-in mitigation can be considered only in cases of new and proposed land-use facilities. Hazards associated with existing land uses, which are often exempt from changes to zoning, pose a different challenge and underline the need to enlist the help of wildlife-management professionals.14

In part, this is because mitigation measures are site-specific; they’re best designed and implemented according to the unique characteristics of each land use:

- Location with respect to an airport, and other land uses;

- Types of activity undertaken on site; and

- Types and numbers of wildlife that frequent, or reside on, the land use.

Wildlife-management professionals will consider these and other factors in recommending and implementing effective mitigation measures.15

13 Average weight of a Snow Goose is 2.4 kg. Since the aircraft was traveling at approximately 175 mph, the impact force of each strike would likely exceed 10,000 pounds.

14 Contact airport operators for information on local wildlife-management experts.

15 Sharing the Skies: An Aviation Industry Guide to the Management of Wildlife Hazards (TP13549) and the Wildlife Control Procedures Manual (TP11500) can be downloaded from the Transport Canada website: https://tc.canada.ca/. These publications offer excellent guidance on wildlife-hazard mitigation, which should be enacted only by specialists in the field.

An eye on the big picture

INTEGRATING WILDLIFE-MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES

Section 3, Building an Effective Response, discussed the idea of matching airport - area ecosystems with effective air-safety systems, which comprise a variety of parties - property and business owners, facility operators and governments among them. In most cases within this system, only airport operators are obliged by regulation to undertake wildlife-management activities. The involvement of non-aviation stakeholders introduces unique issues. Organizations newly engaged in these activities differ considerably. Most lack technical knowledge related to wildlife management. Many employ different operational and organizational styles. Some lack experience in coordinating activities within their own organizations, much less in conjunction with others. Some exist to maximize profits, others to optimize service delivery and minimize expenditures. Each company and organization has its own interests, and its own incentives to manage wildlife hazards. Some are compelled to act in the public interest, others through decisions to reduce potential liability in the event of aircraft accidents that involve wildlife strikes.

The airport bird-hazard risk analysis process supports all system stakeholders, regardless of motivation. ABRAPs recognize individual stakeholders as equal partners in efforts to improve aviation safety. The process also promotes collective efforts, however, demonstrating that there’s not only strength in numbers, but also potential cost savings.

For example, neighbouring land uses could compare efforts, finding ways to combine skills, share resources and streamline mitigation activities.

The key is coordination and integration. By working together, airport operators, property and business owners, and governments at all levels have the opportunity to reduce land-use wildlife hazards and improve operational safety at airports throughout Canada.

16 See case study two, Sharing the Skies: An Aviation Industry Guide to the Management of Wildlife Hazards (TP13549), p. 151. See Resources.

Mitigation need not be highly technical, or expensive |

| For example, dogs are often used to scare birds from golf courses. Such mitigation techniques, however, must be co-ordinated among airport-area stakeholders to ensure that efforts to drive hazardous species from one location do not simply result in their appearance at another site. |

Resources

DOCUMENTS AND LINKS

| DOCUMENT TITLE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Airport Bird Hazard Risk Analysis Process (Transport Canada, 2004) https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/airport-wildlife-management-bulletins-tp-8240/airport-wildlife-management-bulletin-tp-8240-no-38/airport-wildlife-management-bulletin-tp-8240-no-38-appendix-b | This document contains the original presentation of ABRAP and provides considerable additional background and detail for those interested in learning more about the process. |

| Bird Use, Bird Hazard Risk Assessment, and Design of Appropriate Bird Hazard Zoning Criteria for Lands Surrounding the Pickering Airport (Transport Canada, 2002. LGL Limited report no. TA2640-2.) | This document describes application of ABRAP in assessing risks associated with development of the proposed Pickering Airport near Toronto. |

| Height Distribution of Birds as Recorded by Collisions with Civil Aircraft (U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2004 Auk [in review].) | This formal paper was pre p a red by Dr. Richard A. Dolbeer, chair of Bird Strike Committee USA and a recognized authority in the field. |

| Land Use in the Vicinity of Airports (TP 1247) https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/aviation-land-use-vicinity-aerodromes-tp-1247 |

This was the sole publication used prior to the d e velopment of ABRAP to provide guidance concerning airport - a rea land-use activity. |

| Liability Issues Associated with Waste Disposal Facilities and other Land Uses as they may affect Aviation Safety by virtue of Attracting Birds ( LGL Limited for Transport Canada, 2004.) | Transport Canada commissioned this study of legal liability associated with the matter as part of its effort to examine safety issues related to airport - area land uses. |

| Pickering Airport Site Zoning Regulations: Mitigation of Bird Hazards Arising From Particular Land Uses (Transport Canada, 2004. LGL Limited report no. TA2916-2.) | Mitigation of bird hazards is discussed at length in this document. Note that these mitigations are site-specific. Interventions considered for the Pickering area would not necessarily be appropriate elsewhere. |

| Safety Risk Assessment of Canada Geese and Aircraft Operations in the Greater Toronto Area (SMS Report no. 401) | This document examines risks posed to aircraft operations by growing populations of Canada Geese in the GTA. |

| Sharing the Skies: An Aviation Industry Guide to the Management of Wildlife Hazards (TP13549) https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/sharing-skies-guide-management-wildlife-hazards-tp-13549 |

These Transport Canada publications provide direction on a wide range of issues concerning airport wildlife management. Of particular note in this case is the guidance these documents provide regarding mitigation procedures. |

| Wildlife Control Procedures Manual (TP1150) https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/abstract-wildlife-control-procedures-manual-tp-11500 |

|

| System Safety Review of Land Use in the Vicinity of Vancouver International Airport (Transport Canada, 2004) | This study, which helped examine risks associated with runway expansions at Vancouver International Airport , was one of the first applications of ABRAP. |

17 Note that ABRAP language associated with many of these documents has in some cases been revised since their initial publication. Refer to Safety Above All for the most recent terminology.

Safety Above All

A COORDINATED APPROACH TO AIRPORT-VICINITY WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

Lands surrounding Canada’s airports are subject to a variety of uses: agricultural, commercial, recreational and industrial. While undeveloped areas hold obvious appeal to wildlife, animals are no less attracted to many man-made land uses. Landfills can provide ready sources of food. Golf courses may offer food, water and shelter. Airports themselves often provide protected roosting and nesting areas.

Natural movements among these land uses often take wildlife through air-traffic zones on the ground and in the air, including runways, taxiways, and approach and departure paths. In response to the resulting risks to aviation safety, Transport Canada has developed a comprehensive, multi-step process through which all airport-area stakeholders can work collectively to reduce wildlife hazards.

Safety Above All introduces this process, providing a concise overview of coordinated measures that airport operators, property and business owners, and governments at all levels can use to manage wildlife hazards in areas around Canada’s airports.

Transport Canada

Aerodromes and Air Navigation Branch

Wildlife Division