On this page

Background: Vehicle immobilizers

Anti-theft immobilization devices are systems that assist in preventing the unauthorized use of a vehicle. Such a device, when armed, prevents the activation of a control unit, such as the engine control unit, the fuel control unit, or the ignition control unit. To disarm the system, a coded key, a keypad or a remote device is required.

Road safety in Canada is a shared responsibility among all levels of government, industry partners, and all road users. Under the Motor Vehicle Safety Act, Transport Canada is responsible for establishing safety standards and regulations for new and imported vehicles, tires, and child restraints. In this regard, vehicle manufacturers and importers must certify that all vehicles imported to Canada or manufactured in one province and sold in another comply with all applicable safety regulations and safety standards in effect on their date of manufacture. Provincial and territorial governments are responsible for driver licensing and vehicle registration, vehicle maintenance and the installation of aftermarket equipment, as well as setting and enforcing the rules of the road, including those associated with new vehicle technologies.

In 2005, motor vehicle theft became a significant issue for many Canadians. Motor vehicles were generally stolen either for profit or for convenience. Theft of vehicles for profit was frequently attributed to organized crime and insurance fraud, whereas theft for convenience was attributed to joyriding. As is still the case today, there were many innocent victims when a vehicle was stolen, including the vehicle owner, the insurance company, and subsequent owners who unknowingly purchased stolen vehicles or stolen vehicle parts, all experienced a loss. But more importantly, theft by young offenders frequently led to collisions which resulted in serious injuries and death.

Introduced in 2005 and effective as of 2007, the subject of theft protection has been addressed through a safety lens in the Canada Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (CMVSS) 114 – Theft Protection and Rollaway Prevention. This standard requires that vehicles of certain prescribed classes (passenger car, every three-wheeled vehicle, and every multi-purpose passenger vehicle and truck with a GVWR of 4 536 kg or less and, with the exception of a walk-in van) that are imported to Canada or manufactured in one province and sold in another – be equipped with an immobilization system if they are manufactured after 2007. Immobilization systems reduce theft for convenience (joyriding), which has been directly linked to serious road safety issues (e.g., inexperienced drivers) as the offender is often a youth with limited driving skills. The same safety linkage has not been made in the context of professional, for-profit theft. The safety standards prescribe that the immobilization system must be designed to meet one of four options for compliance listed in CMVSS 114 subsection (4):

- National Standard of Canada CAN/ULC S338-98 (May 1998);

- Part III of United Nations Regulation No. 97 (8 August 2007);

- Part IV of United Nations Regulation No. 116 (10 February 2009); or

- Requirements set out in subsections (8) to (21) of CMVSS 114.

In addition to these immobilizer requirements, vehicle identification number plates must be installed on the frame of a vehicle, making it more difficult to alter or replace a vehicle identification number.

Vehicle theft for profit is a highly lucrative, highly sophisticated trans-national crime that not only affects Canadians, but empowers criminal organizations through the proceeds of crime. Changes in vehicle technologies, and available technologies to facilitate the theft of vehicles, coupled with a lucrative demand for stolen vehicles outside of Canada, has resulted in a recent increase in stolen vehicles in Canada.

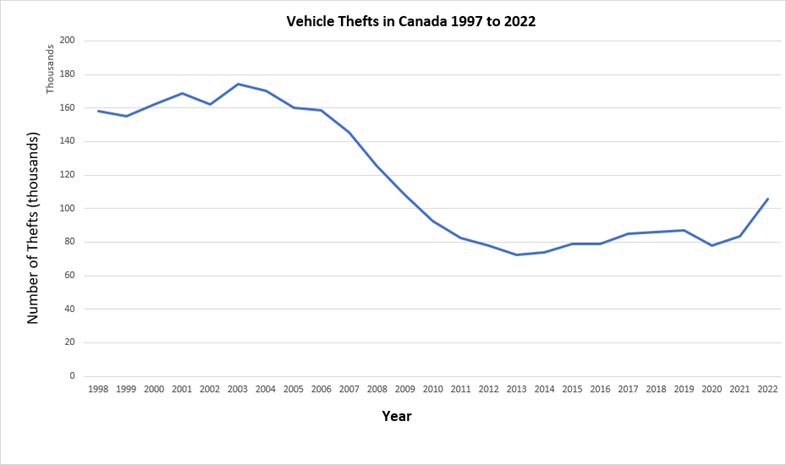

The graph below showcases the effect of the adoption of CMVSS 114 in 2007 (50% decline) and the recent uptick in vehicle theft. Regulations must undergo a rigorous process of testing, validation, cost benefit analysis, and stakeholder consultation to ensure that regulations will indeed provide the intended benefits while not causing excess burden on stakeholders and can take several years to be completed.

In light of the recent resurgence of vehicle thefts, the Government of Canada hosted a National Summit on Combatting Auto Theft on February 8, 2024, which brought together federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal governments; industry leaders; and law enforcement representatives. Discussions at the Summit advanced work to keep Canadians safe and prevent auto thefts from occurring; to recover vehicles that have been stolen; and to ensure that the perpetrators of these crimes are brought to justice. At the conclusion of the Summit, a Statement of Intent was announced regarding combating auto theft and the Government of Canada committed to the release of an Action Plan. The Action Plan can be found at the following link: National Action Plan on Combatting Auto Theft.

History of CMVSS 114 and immobilization standards

In 2000, Transport Canada, in partnership with the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, the Solicitor General of Canada and the Department of Justice’s Business Action Program on Crime Prevention, part of the Business Alliance on Crime Prevention, examined a number of issues surrounding vehicle theft including vehicle identification, youth crime and theft prevention. One of the issues reviewed was vehicle parts marking.

Since 1985, in the United States (U.S.), the Department of Transportation requires, under the Code of Federal Regulations Title 49, Part 541, that some vehicle lines have several of the vehicle’s parts marked with the Vehicle Identification Number (VIN). Parts marking assists in the identification of a vehicle in cases where the VIN plate has been replaced or destroyed, or when a vehicle has been dismantled with the intent of selling its individual parts. The U.S. safety standard extends only to high theft vehicle lines, and exemptions from the parts marking requirement may be granted to vehicle lines equipped with an effective immobilization system.

In 2002, Transport Canada began negotiations with vehicle manufacturers to establish a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to voluntarily raise immobilizer fitment from the estimated 80% of vehicles, to 100% implementation. However, negotiations failed due to the reluctance of some manufacturers to agree to the proposed requirements. Consequently, the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations were amended to require Transport Canada to mandate the installation of an immobilization system on some prescribed classes of vehicle. This amendment was published on March 9, 2005, with a mandatory compliance effective date of September 1, 2007. The following link can be referred to for the Canada Gazette, Part II publication: Canada Gazette Part II – Regulations Amending the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations (Locking and Immobilization Systems) – March 9, 2005 (PDF, 812 KB).

Before the introduction of immobilization systems resulting from the 2005 amendment, young offenders were involved in a substantial proportion of motor vehicle thefts in Canada, and joyriding was primarily a youth crime. This type of vehicle theft created a significant road safety hazard, as young offenders were frequently inexperienced drivers and tended to take unnecessary risks. Peer pressure and thrill seeking appeared to motivate many of these thefts, and intoxicating substances such as alcohol and drugs often played a role. These thefts very often resulted in injury and death. Prior to its Canada Gazette Part II publication from 2005, Transport Canada considered whether vehicles should also be required to have their parts marked, and concluded that this requirement on Canadian vehicles would do little to improve road safety for Canadians.

In the original implementation of immobilization systems in 2005, Transport Canada allowed companies flexibility in their choice of immobilization systems, in a way that did not compromise the level of road safety in Canada.

In 2007, new technologies and revisions to the U.S. safety standard eliminated the requirement to use a conventional key and eliminated the need to install a steering lock. As a result of this change in the U.S., and to harmonize the Canadian and U.S. safety standards, Transport Canada amended its requirements and introduced a new definition for the term “key”; provided additional key removal and transmission override options; and harmonized the steering lock requirements and test procedures with regards to vehicle motion.

The amendment also added a new compliance option for immobilization systems (Part IV of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (ECE) Regulation No. 116 – later renamed as United Nations Regulation No. 116) and clarified test requirements of the Canadian safety standard by removing performance tests concerning environmental durability and electrical testing.

In 2009, Transport Canada updated the standard to remove incorrect references and irrelevant information to some requirements of ECE Regulation No. 97 Part III (now known as United Nations Regulation No. 97 Part III).

In 2011, Transport Canada amended Section 114 of Schedule IV of the Motor Vehicle Safety Regulations by introducing new provisions that updated the vehicle safety immobilization system requirements by addressing new and emerging technologies as they apply to original-equipment manufacturers. This amendment was initiated through a working group with Transport Canada and key representatives of the two automotive manufacturing associations of Canada: the Global Automakers of Canada (GAC), formerly known as the Association of International Automobile Manufacturers of Canada (AIAMC), and the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association (CVMA).

The amendment removed requirements that may have prevented new vehicle immobilization systems or technologies such as keyless entry, remote start systems and key replacement systems. This resulted in the development of a fourth alternative to the immobilization system requirements that addressed the new technologies, as they apply to the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM), while maintaining the current high level of safety. After a consensus was reached, this fourth alternative was circulated for general consultation to obtain comments from additional interest groups, which further assisted in developing the amendment.

Along with this fourth alternative to compliance, references to both European regulations were updated to include the most recent versions of these regulations. These changes were non-substantive relative to the previous Canadian requirements, and improved harmonization.

Since the latest change to CMVSS 114 in 2011, three of the four immobilization system options offered in CMVSS 114 have been updated:

- The National Standard of Canada CAN/ULC S-338 was updated once, with the latest update being in July 2023.

- The United Nations (UN) Regulation No. 97 was updated a number of times, with the latest content update being in July 2011 (latest administrative update December 2021, allowing equivalency to UN Regulations 162 & 163).

- The UN Regulation No. 116 was updated a number of times, with the latest update being in September 2023.

As CMVSS 114 references specific versions with specific dates of the above options, a regulatory change is required every time they are updated, and they are currently out of date. However the updates would not improve the overall stringency. With respect to the United Nations (UN) Regulations, in 2021, UN Regulation Nos.161, 162 and 163 were published with the aim of simplifying and dividing overlapping theft protection regulations (UN Regulation Nos. 18, 97 and 116). As such, UN Regulation No. 161 contains requirements for devices against unauthorized use; UN Regulation No. 162 contains requirements for immobilization systems; and UN Regulation No. 163 contains audible sound requirements for the vehicle alarm systems. Technical Standards Document 114 referenced in CMVSS 114 contains provisions similar to UN Regulation No. 161, CMVSS 114 requires an immobilization system similar to UN Regulation No. 162 (as mentioned above). UN Regulation No. 163 is not mandatory, as it only applies if a manufacturer chooses to install an alarm system that produces audible sounds. Canada does not provide requirements if a manufacturer chooses to install an alarm system that produces audible sounds when the alarm is triggered.

Upon publication of these new regulations, UN Regulations Nos. 18, 97 and 116 were updated to indicate that vehicles complying with the new regulations also equates to compliance with the sections containing the same requirements in the older regulations (i.e., a system meeting UN Regulation No. 162 would also meet Part III of UN Regulation No. 97 and Part IV of UN Regulation No. 116). As such, Transport Canada could reference UN Regulation No. 162 in lieu of the current UN Regulation Nos. 97 and 116. Note that since its introduction in 2021, UN Regulation No. 162 has been amended 4 times.

The fourth option for immobilization requirements is set out in subsections (8) to (21) of CMVSS 114. These sections have not been updated since they were published in 2011. Research and public consultation on any potential changes would be required before any amendments could be proposed for these sections.

Consultation questions

- What are your thoughts on updating the reference to CAN/ULC-S338-98 (May 1998 version) to its latest 2023 version?

- Given the UN Regulation 162 supersedes UN Regulation No. 97 and UN Regulation No. 116, what are your thoughts on Transport Canada allowing only UN Regulation No. 162?

- Transport Canada is considering referencing all the immobilization options in an ambulatory manner (meaning the regulation always references the latest version of the options as they get updated) rather than referencing a specific version of them within CMVSS 114. This means that companies would need to update their systems and documentation anytime there is an optional update. What are your thoughts on this?

- Due to the advancements in theft methods and evolving vulnerabilities in anti-theft systems, would you be in favor of removing Sections 8 to 21 of the CMVSS 114 and possibly reintroducing more stringent requirements at a later date? If so, why?

- If the regulations were to be updated, what lead time for mandatory compliance would be necessary to implement the changes?

You can email us your comments at RegulationsClerk-ASFB-Commisauxreglements@tc.gc.ca, and include “Theft Protection Informal Consultation” in the subject line.

If you provide comments via submission or e-mail, as set out in sections 19 and 20 of the Access to Information Act, be sure to identify any parts of your comments that we shouldn’t make public if they include personal information or third-party information. Explain why your comments should be kept private, and for how long. Unless you specify that a section is private, it may be included in any regulatory proposal that Transport Canada publishes in the Canada Gazette.