As part of the Oceans Protection Plan, following changes to the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 completed in 2023 to strengthen marine safety and environmental protection, Transport Canada is working to develop some new rules and processes to improve preparedness and response for marine incidents. This discussion paper describes our intentions and provides an opportunity for Indigenous peoples, coastal communities, and marine stakeholders to share their views.

On this page

- Executive summary

- Guiding principles

- Enhancing marine safety

- Preparing for and responding to marine pollution

- Share your comments

Executive summary

Canada is a maritime country with the longest coastline in the world. Canadians rely on oceans and waterways for food, recreation, transportation, and for shipping many products we use every day. The Government of Canada has worked to build a strong marine safety system that protects marine environments and coastal communities while also supporting safe and clean marine shipping which is vital for supply chains and our broader economy.

The Oceans Protection Plan aims to strengthen marine safety and environmental protection. In support of this goal, amendments to the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 were made in 2023 to further improve how Canada prepares for and responds to marine emergencies and pollution incidents.

As next steps, Transport Canada is proposing to create new regulations in two areas:

- Enhancing marine safety response:

- a) Requiring certain vessel types to have arrangements in place to access marine emergency services if there is an incident (for example, marine firefighting and assistance to disabled vessels)

- Preparing for and responding to marine pollution incidents:

- a) Improving how vessels and handling facilities prepare for and respond to marine incidents that involve hazardous and noxious substances

- b) Introducing a response coordinator role to improve response to all types of pollution incidents

This discussion paper seeks your input to help determine the scope and key features of future regulations like:

- Which vessel types should have emergency services arrangements?

- What requirements should be included in the arrangements?

- Which vessels and handling facilities should have hazardous and noxious substances response plans?

- What requirements should be included in the response plans?

- What responsibilities and capabilities should the response coordinator have?

Your comments will help Transport Canada refine the proposed regulatory approach. This paper is an initial step to help determine the scope of possible regulations in the identified areas. There will be more opportunities to provide your comments as Transport Canada continues to develop proposed regulations in more detail.

Guiding principles

We are proposing the following principles to guide our work to develop potential regulations:

- risk generators remain responsible for preparing for and responding to incidents

- support integrated incident response with clear roles and responsibilities

- evidence-based and risk-informed requirements

- flexible regulatory and program design to reflect evolving and varying risks

- response capacity aligned with risk

- complement and work with existing regulations, programs, and practices

- impacted parties have opportunities to help design and develop new regulatory proposals

More information on the proposed guiding principles can be found in Annex A.

Questions for consideration

- Which principles are the most important for you? Why?

- In your view, are there other principles that should be considered? If so, what are they and why are they important?

Enhancing marine safety

Marine emergency services arrangements

Marine emergency management is a broad term which includes preventing, preparing for, reducing the impacts of, and responding to marine incidents. Marine emergencies include events such as when a vessel:

- sinks

- founders (cannot move) or capsizes

- is involved in a collision

- has a fire or an explosion

- goes aground

- has damage that affects its seaworthiness or makes it unfit for its purpose

- goes missing or is abandoned

How Canada prevents and responds to marine safety incidents

To help prevent marine incidents, large cargo vessels in Canada’s waters are subject to rigorous international and Canadian requirements. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea imposes comprehensive safety requirements on a ship’s construction, subdivision, stability, strength, fire protection, fire detection and fire extinction, machinery, radiocommunications, safe navigation, safety equipment, firefighting equipment, safe stowage and securing of cargo, and safety management.

Currently, vessel owners and operators are responsible for:

- safely operating and navigating their vessels

- making sure officers and crew have the right skills and experience

- keeping passengers safe

- preparing for and responding to marine incidents

If an emergency occurs, the vessel owner or operator may work with different groups to resolve the issue. These groups could include:

- commercial responders and contractors

- federal departments (e.g., Canadian Coast Guard and Transport Canada)

- Indigenous communities

- port authorities

- scientific experts

- provincial and municipal governments

Why regulate?

Although there are multiple prevention measures in place and shipping accidents occur at a low rate (see Annex B), it is still important for vessel owners and operators to be able to respond effectively and reduce impacts on mariners, passengers, coastal communities, and marine ecosystems. Marine safety incidents can escalate quickly, posing risks to lives or increasing the risk of a pollution release.

Although marine emergency services like marine firefighting and disabled vessel assistance are available on a commercial basis, there may be different types and levels of marine emergency services available along a coast, depending on the level of marine traffic, risk, and commercial capacity. This means that there may be gaps, limited coverage, or differences in how quickly services can be deployed. For example, in 2019, a fire on-board the M.V. Tecumseh required marine firefighting specialists to be brought from Texas to put it out. Additionally, marine firefighting and salvage assistance for the Zim Kingston incident in 2021 was available through arrangements that were in place to meet United States requirements.

A regulated approach would facilitate more consistent and quicker responses, and earlier intervention to prevent incidents from becoming worse.

What we are proposing

We want to improve marine emergency management so that vessels can have faster, consistent access to marine emergency services so that risks can be addressed earlier to help protect people on-board, the marine environment, and the stability of the supply chain.

Transport Canada is proposing to develop regulations that would require certain commercial vessels to have marine emergency services arrangements starting with services that are commonly used such as marine firefighting services, and assistance for disabled vessels, which include salvage and emergency towing services.

As part of the proposed regulations, Transport Canada would work to create clear definitions for the proposed services based on the feedback we receive. To help with the discussion, we can consider the following definitions from other regimes:

- marine firefighting: U.S. regulations define this as "any firefighting-related act undertaken to assist a vessel with a potential or actual fire, to prevent loss of life, damage or destruction of the vessel, or damage to the marine environment."

- assistance for disabled vessels: The International Maritime Organization defines salvage as “any act or activity undertaken to assist a vessel or any other property in danger in navigable waters or in any other waters whatsoever.”

For the Canadian Coast Guard, “disabled” refers to a vessel that is afloat and not in immediate danger, but has lost all means of propulsion, steering or control to such a degree as to be incapable of proceeding to safety without assistance. Assistance such as search and rescue services when there is a grave and imminent danger and immediate assistance is required, and the removal of wrecks, are already addressed through existing programs, legislation, and regulations.

We could also consider requirements like the U.S. for access to marine emergency services. U.S. regulations require vessel owners to have arrangements in place as part of their response plans, including for example, the planned availability of these services, drills and exercises, equipment compatibility, and facilitating coordination between different emergency responders (see Annex D).

It is important to note that Transport Canada does not propose:

- changing the roles and responsibilities. Vessel owners would remain responsible for preparing for and responding to all types of pollution incidents, including hazardous and noxious substances

- taking on the role of overseeing response contractors as this would be the responsibility of the vessel owner/operator

- regulating the professional qualifications for marine emergency responders such as marine fire-fighters

- mandating specific organizations to manage all marine emergencies, as it would be the responsibility of vessel operators to create a pollution response plan and employ a response coordinator to implement the plan

Oil spill preparedness and response services would not be included as part of the proposed regulations for emergency services arrangements. Certain vessels are currently required under regulation to have an arrangement with a Transport Canada-certified response organization in the event of an oil spill.

Questions for consideration

- Do you agree that future regulations could start by focusing on marine firefighting and assistance for disabled vessels?

- Which vessels do you think should have arrangements for emergency services? (For example: based on the vessel type or size? The type of product being carried? The vessel route and proximity to port or population centres?)

- What key elements do you think should be included in the emergency services arrangements? (For example: when arrangements must be activated? Standards for planned availability of services? Service provider capabilities?)

- What could be important regional considerations for emergency services? (For example: environmental or cultural sensitivities? Areas with more shipping traffic? Existing response capabilities?)

Preparing for and responding to marine pollution

Hazardous and noxious substances

A hazardous and noxious substance is any substance other than oil that, if introduced into the marine environment, is likely to:

- create hazards to human health

- harm living resources and marine life

- damage amenities

- interfere with legitimate uses of the marine environment

A hazardous and noxious substances handling facility is a facility that is used or that will be used in the loading or unloading of hazardous and noxious substances to or from vessels. Our focus is on substances that are carried as cargo or fuel. Other possible pollutants related to vessel operations like sewage and garbage are addressed under the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations.

Transporting hazardous and noxious substances by ship and loading or unloading them at handling facilities like ports and marine terminals is an important part of Canada's trade. Hazardous and noxious substances can include substances transported in bulk as liquids, liquefied gases, solid materials and materials in packaged form. They can include products useful to Canadians like household goods, or materials used for infrastructure, agriculture, manufacturing, and more.

Although large releases of hazardous and noxious substances in Canadian waters have been rare, these substances can float, dissolve, or sink in water, evaporate into the atmosphere, or have multiple different reactions. Vessels that commonly carry hazardous and noxious substances include bulk carriers, chemical tankers, and container ships.

How Canada prepares for and responds to hazardous and noxious substances incidents

There are well-established international standards that address packaging, storage, and segregation of various products. Canada also has multiple measures in place to prevent incidents involving hazardous and noxious substances, including:

- applying international standards like those mentioned above

- using navigation aids and vessel traffic services

- requiring mandatory reporting for potential (and actual incidents)

- creating standards for the packaging and stowage of substances

Vessel owners are responsible for preparing for and responding to incidents of all types of pollution, including hazardous and noxious substances. Transport Canada regulations require vessels over a certain size or carrying oil or noxious liquid substances to have on-board response plans in the event of a spill. Pollution incidents are addressed through either on-board equipment and/or commercial arrangements with contractors with the appropriate expertise and equipment. The Canadian Coast Guard responds when the polluter is unknown, unwilling, and unable to respond.

Why regulate?

While Canada’s marine safety system largely aims to prevent incidents involving hazardous and noxious substances, readiness and response is largely provided through commercial arrangements. As well, the current preparedness and response requirements are focused on some types of substances, such as oil and noxious liquid substances.

The volume and range of hazardous and noxious substances are expected to increase, and even smaller releases can impact the environment, communities, and responders, and disrupt supply chains and community re-supply, which in turn can affect the economies of Canada and the local communities.

Given historically limited volumes of hazardous and noxious substances being moved by ship, response resources and expertise for hazardous and noxious substances may be limited or uneven across a coastal region. This can lead to differences in how quickly or effectively response operations can be implemented.

New regulations can help make sure response plans for hazardous and noxious substances are in place for both vessels and handling facilities to act quickly to contain, clean-up, and reduce risks and potential damage, tailored to the specific products involved.

In addition, a hazardous and noxious substances preparedness and response framework would enable Canada to accede to the International Maritime Organization’s Protocol on Preparedness, Response and Co-operation to Pollution Incidents by Hazardous and Noxious Substances. This would enable Canadian responders to cooperate with and have access to additional response capacity from other maritime countries.

What we are proposing

Transport Canada wants to develop regulations that keep Canadians safe and support rapid, effective, and consistent response to marine incidents involving hazardous and noxious substances. This would help reduce negative impacts on the marine environment, human health, and supply chains, if this type of incident occurred.

New regulations would build on Transport Canada’s existing models for marine oil spill preparedness and response, and the transportation of dangerous goods regime.

We are considering which vessel types and handling facilities should have pollution response plans for hazardous and noxious substance incidents and what these plans should include. The proposed requirements for pollution response plans could be based on factors such as:

- the size and/or class or vessel

- whether the vessel is carrying certain types or volumes of hazardous and noxious substances as cargo or fuel

- the type and volume of hazardous and noxious substances loaded or unloaded at a handling facility

- the nature of products and hazards posed

- risks to human health and the environment

Similar to response plans for vessels carrying oil, response plans for prescribed vessels carrying hazardous and noxious substances could include:

- reporting procedures and a list of authorities to contact

- identifying training and equipment

- specialized safety or containment requirements

- a description of response actions to take

Like oil handling facilities, prescribed hazardous and noxious substances handling facilities could be required to have plans to prevent and respond to incidents, which could identify:

- procedures to be followed

- required training, exercises, and equipment

- resources needed to respond to a release or potential release of hazardous and noxious substances

Transport Canada is also considering that vessels or handling facilities that transport or transfer both oil and hazardous and noxious substances would be able to combine their plans into a single marine pollution response plan.

Vessel owners would continue to be responsible for the safety and control of the vessel, including preparing for and responding to pollution incidents. Transport Canada is not proposing to take on the role of certifying individuals or organizations to respond to hazardous and noxious substances incidents. Unlike for oil spill response, where Transport Canada certifies specific organizations to respond to oil spills from ships within a geographic area, the variety of hazardous and noxious substances makes it difficult for any single organization to respond to a range of possible hazardous and noxious substances incidents. Responding to hazardous and noxious substances incidents may require special training or expertise depending on the substance involved.

Questions for consideration

- What factors do you think are important for requiring vessels to have hazardous and noxious substances response plans? (For example: Vessel size? Vessel location? Hazards posed by cargo?)

- What factors do you think are important for requiring hazardous and noxious substances handling facilities to have response plans? (For example: Type or amount of goods handled? Location of facility? The types of vessels loaded or unloaded?)

- What do you think should be included in the emergency plans? (For example: When the plan is activated? Who must be contacted? The activities and procedures that must be followed?)

Response coordinator for marine pollution incidents

Transport Canada wants to create a shore-based response coordinator role to improve response to all types of pollution incidents. The response coordinator could be a specialized person or entity identified to work on behalf of a vessel to manage and coordinate the response to pollution incidents including implementing the vessel’s emergency plans. This would be a different role than the “Authorized Representative” who is responsible for a vessel and its overall compliance with legislation and regulations.

Why regulate?

Marine pollution incidents can be complex and require many people and organizations to coordinate and work together. To enable better coordination and a more efficient pollution response, a response coordinator representing the vessel owner could promote smoother execution of response plans by ensuring that a single, specialized coordinator is available to execute them. A response coordinator can also help manage the overall incident while the vessel crew may be undertaking specific response activities. The response coordinator would be responsible for the vessel owner’s response activities and could help make sure response is efficient and well-coordinated.

What we are proposing

We are considering requiring vessels that have a shipboard response plan for oil, noxious liquid substances (both existing requirements under the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations), or hazardous and noxious substances (as proposed above) to designate a shore-based response coordinator as part of their response plan.

The response coordinator would be an individual or organization that would implement a vessel’s pollution response plans when an incident occurs. A similar role exists in the United States where an on-shore “Qualified Individual” manages the incident on behalf of the vessel owner. The response coordinator would be responsible for managing the vessel owners’ response activities, including activities such as authorizing funding, assessing environmental risk, and coordinating with the Canadian Coast Guard and other emergency responders and authorities. The response coordinator would be required to have knowledge of national and regional marine pollution contingency plans and the legal requirements related to preparing for and responding to marine pollution.

Questions for consideration

- What capabilities and responsibilities do you think a response coordinator should have? (For example: Authorizing company funds? Coordinating with responders? Familiarity with response practices and procedures?)

Share your comments!

Transport Canada encourages you to email your comments to: OPP.EMEM.HNS-PPO.AGUM.SNPD@tc.gc.ca. We will consider the comments that you share and will work to incorporate your feedback to further develop our proposed regulations. A “What We Heard” report will be made available.

Annex A: Proposed guiding principles

We are proposing the following principles to guide our work to develop potential regulations:

Risk generators remain responsible for preparing for and responding to incidents.

Those who contribute to the risk of marine emergency or pollution incidents, such as vessel owners and operators or handling facility operators, are responsible for preparing for and responding to incidents. This can include having procedures, plans, resources, equipment, and contracts in place and responding when an incident occurs.

Support integrated incident response with clear roles and responsibilities.

New rules and processes should support an integrated response system that addresses both safety and pollution incidents, encourages collaboration, and reflects clear and consistent roles and responsibilities, where different actors understand their obligation, actors could include:

- federal, provincial, and local governments

- Indigenous communities

- ports and marine facilities

- vessel owners and operators

Evidence-based and risk-informed requirements.

Future regulations should be developed based on understanding the likelihood of incidents occurring and how they could impact the environment and coastal communities.

Flexible regulatory and program design to reflect evolving and varying risks.

Potential regulations and programs should be flexible enough to adapt and reflect how risks and the way they are managed may vary or evolve across different coasts and situations.

Response capacity aligned with risk.

Response capacity should reflect the likelihood of incidents, the potential severity of impacts, and the nature and type of risks and impacts.

Complement and work with existing regulations, programs, and practices.

Regulation and program proposals should be compatible and work seamlessly with existing domestic and international preparedness and response systems and practices.

Impacted parties have opportunities to help design and develop new regulatory proposals.

Indigenous peoples, coastal communities, other levels of government, and marine industry stakeholders will have multiple opportunities to share their views and provide input and their views will be considered to help design regulatory proposals.

Annex B: Volume and types of commercial vessel traffic in canada

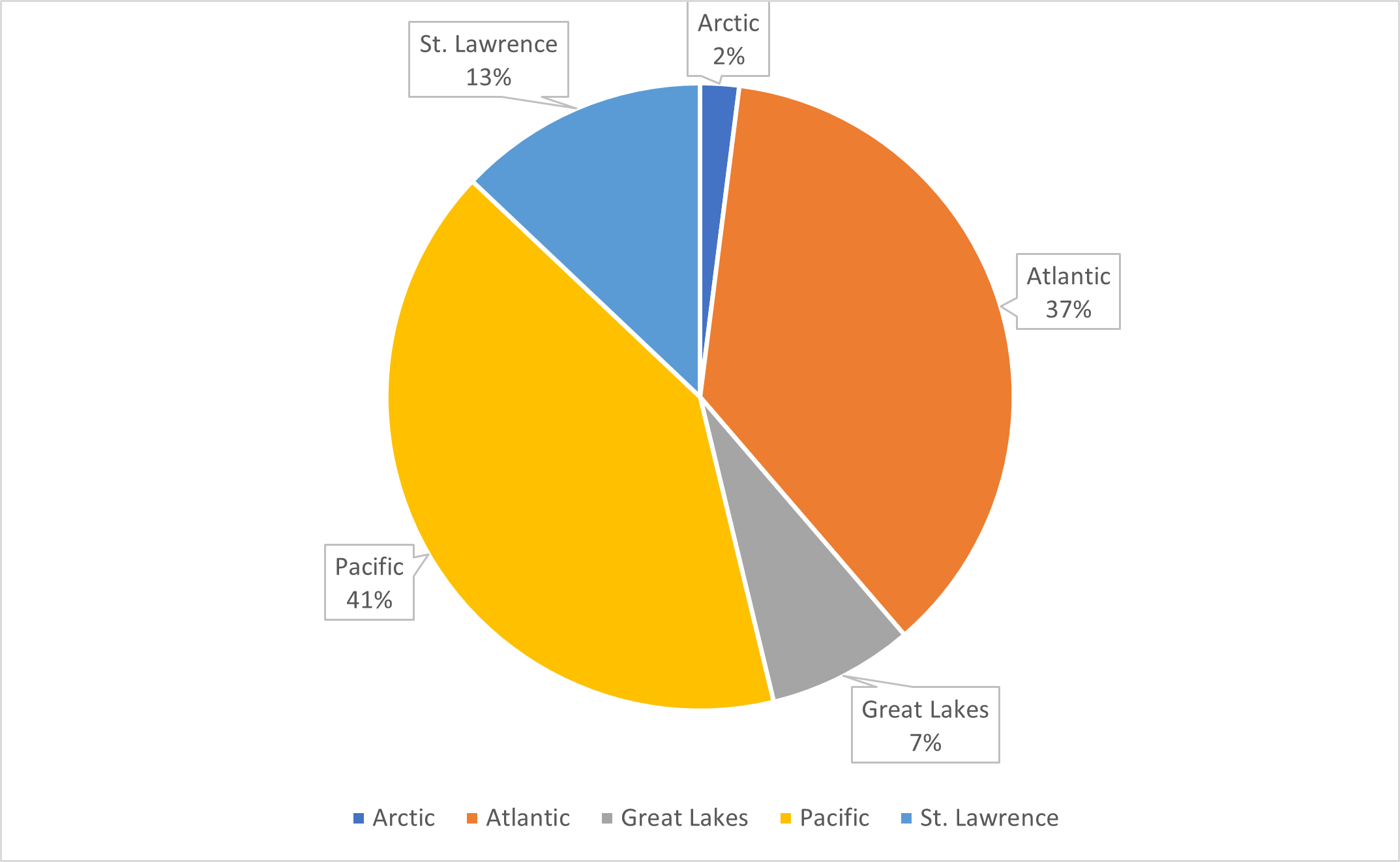

Based on traffic data from Transport Canada, Figure 1 shows the total marine traffic by region. Figure 2 shows the type of vessels by nautical mile for each coastal region.

Commercial vessels include:

- cargo

- container

- dry bulk

- ferry/ro-ro

- fishing

- passenger

- tanker

- tug/port vessels

Figure 1: 2022 regional commercial vessel traffic distribution, by total nautical miles sailed

Figure 2: 2022 regional commercial vessel traffic, by nautical miles sailed

| Type of vessel | Arctic | Atlantic | Great Lakes | Pacific | St. Lawrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo | 114,242 | 697,237 | 132,958 | 704,008 | 421,614 |

| Container | 5,243 | 1,289,846 | 28,634 | 1,024,183 | 454,705 |

| Dry Bulk | 66,156 | 1,622,009 | 1,020,039 | 1,158,764 | 1,092,132 |

| Ferry/Ro-Ro | 3,069 | 727,889 | 79,145 | 1,493,576 | 273,159 |

| Fishing | 154,138 | 3,102,114 | 31,244 | 1,589,379 | 122,798 |

| Passenger | 51,624 | 529,263 | 239,701 | 1,931,171 | 332,642 |

| Tanker | 72,837 | 1,449,016 | 195,555 | 340,827 | 553,124 |

| Tugs/Port | 67,232 | 373,104 | 278,700 | 2,654,310 | 198,953 |

| Total nautical miles sailed | 534,541 | 9,790,477 | 2,005,975 | 10,896,220 | 3,449,127 |

| Percent | 2% | 37% | 8% | 41% | 13% |

Information about the type, frequency and location of marine safety accidents that have occurred in Canada available from the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s 2022 annual reports on Marine Occurrences. The Report states that there were 3.0 shipping accidents per million commercial vessel-kilometers. This is lower than the average of 4.0 shipping accident per million commercial vessel-kilometers over the previous nine years. For context, one million kilometers is the same as circling the globe nearly 25 times.

Data from the Transportation Safety Board gives a sense of the type and location of shipping accidents that occur across Canada. Their report also provides charts that show the number of shipping accidents by type and region, compared with the prior 10-year average.

Annex C: Pollution prevention, preparedness and response

Federal roles and responsibilities

Transport Canada is the lead federal department for managing marine transportation safety in Canada. This includes working with other federal departments like the Canadian Coast Guard and Environment and Climate Change Canada to maintain marine safety and protect the environment by preventing, preparing for, and responding to pollution incidents and vessel emergencies.

The Canadian Coast Guard is the federal authority that makes sure appropriate steps are taken when there may be risks to lives or injuries, and to mitigate, repair, minimize and prevent pollution incidents, including incidents that involve hazardous and noxious substances. The Coast Guard leads the federal response in partnership with other responders from all levels of government to work with or monitor the vessel owner’s response to an incident. The Canadian Coast Guard may take steps to address potential and actual marine pollution throughout an incident, specifically, in cases where the vessel owner or operator is not known, is unwilling, or is unable to respond.

Transport Canada’s pollution prevention and preparedness regulations

Canada already regulates the marine shipping of other types of potentially harmful substances:

- oil is regulated through the Environmental Response Regulations and the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations

- noxious liquid substances are regulated through the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations

- dangerous goods are regulated through the Transport of Dangerous Goods Regulation.

Also, the Marine Liability Act makes vessel owners, including those carrying hazardous and noxious substances, responsible for damages and losses for measures taken by responders.

Canada’s ship-source oil spill preparedness and response regime

Canada requires all “prescribed” oil-carrying vessels (vessels of a certain size and/or class as required under regulations) to have a Shipboard Oil Pollution Emergency Plan (response plan) as detailed in the Vessel Pollution and Dangerous Chemicals Regulations.

Oil handling facilities are required to have both oil pollution prevention plans and oil pollution emergency plans, as outlined in the Environmental Response Regulations.

The regulations require emergency plans to include elements like:

- how the vessel or facility will manage a release

- where equipment and resources will be secured

- what training staff have received

- roles and responsibilities of those involved in response

As well, vessels and oil handling facilities that are located south of 60˚ north latitude are also required to have arrangements with Response Organizations. These are organizations which specialize in oil spill clean-up and that are certified by Transport Canada.

Canada prescribes vessels and handling facilities that are required to have plans and arrangements as follows:

- vessels: an oil tanker of 150 gross tonnes or more, a vessel of 400 gross tonnes or more that carries oil as cargo or fuel, and vessels carrying oil as cargo or fuel engaged in towing or pushing at least one other vessel that carries oil as cargo or fuel with an aggregate tonnage of 150 gross tonnes or more

- oil handling facility: any facility that is used in the loading or unloading of oil to or from a prescribed vessel, these facilities are classified based on their oil transfer rates, and their classification impacts the amount of equipment they must have on-site to respond to a potential release.

Annex D: Marine emergency response (United States)

Emergency Services Arrangements

In many countries, vessel owners are expected to have their own arrangements for emergency services. Generally, governments provide additional response services when required, but vessel owners and operators are ultimately responsible for having services available.

For example, the United States has laws and regulations that specifically require vessel owners to have certain arrangements in place as part of their vessel response plans. Based on the vessel type and the materials they transport, some vessels must have arrangements for marine firefighting and salvage services, including emergency towing. The regulations include timelines for the planned availability of these services that vary by nearshore and offshore zones. As a result, some vessels may have multiple contracts to cover the various geographic regions they move through. The regulations also include many detailed requirements to support the smooth implementation of these service arrangements, like drills and exercises, equipment compatibility, and facilitating coordination between different emergency responders.

Pollution Response – Qualified Individual

In the United States, vessels with emergency plans for oil or dangerous goods are required, as part of those plans, to have access to an on-shore “Qualified Individual” who can manage the incident on behalf of the vessel owner. This person’s duties include activating contracts with emergency responders, liaising with government agencies, assessing environmental risk, coordinating clean-up efforts, and authorizing funding required for response. The Qualified Individual is available on a 24-hour basis and is specialized in executing the emergency plan, supporting fast and efficient response efforts.

Related links

- Preventing spills from vessels

- National Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime

- Improving Canada’s response to hazardous and noxious substances

- Transportation of dangerous goods in Canada

- Marine liability and compensation: Limitation of liability for maritime claims

- Canada Shipping Act, 2001

- Community Participation Funding Program